Colonisation in the Caribbean and Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Update on Systems Subsequent to Tropical Storm Grace

Update on Systems subsequent to Tropical Storm Grace KSA NAME AREA SERVED STATUS East Gordon Town Relift Gordon Town and Kintyre JPS Single Phase Up Park Camp Well Up Park Camp, Sections of Vineyard Town Currently down - Investigation pending August Town, Hope Flats, Papine, Gordon Town, Mona Heights, Hope Road, Beverly Hills, Hope Pastures, Ravina, Hope Filter Plant Liguanea, Up Park Camp, Sections of Barbican Road Low Voltage Harbour View, Palisadoes, Port Royal, Seven Miles, Long Mountain Bayshore Power Outage Sections of Jack's Hill Road, Skyline Drive, Mountain Jubba Spring Booster Spring, Scott Level Road, Peter's Log No power due to fallen pipe West Constant Spring, Norbrook, Cherry Gardens, Havendale, Half-Way-Tree, Lady Musgrave, Liguanea, Manor Park, Shortwood, Graham Heights, Aylsham, Allerdyce, Arcadia, White Hall Gardens, Belgrade, Kingswood, Riva Ridge, Eastwood Park Gardens, Hughenden, Stillwell Road, Barbican Road, Russell Heights Constant Spring Road & Low Inflows. Intakes currently being Gardens, Camperdown, Mannings Hill Road, Red Hills cleaned Road, Arlene Gardens, Roehampton, Smokey Vale, Constant Spring Golf Club, Lower Jacks Hill Road, Jacks Hill, Tavistock, Trench Town, Calabar Mews, Zaidie Gardens, State Gardens, Haven Meade Relift, Hydra Drive Constant Spring Filter Plant Relift, Chancery Hall, Norbrook Tank To Forrest Hills Relift, Kirkland Relift, Brentwood Relift.Rock Pond, Red Hills, Brentwood, Leas Flat, Belvedere, Mosquito Valley, Sterling Castle, Forrest Hills, Forrest Hills Brentwood Relift, Kirkland -

Downloaded4.0 License

New West Indian Guide 94 (2020) 39–74 nwig brill.com/nwig A Disagreeable Text The Uncovered First Draft of Bryan Edwards’s Preface to The History of the British West Indies, c. 1792 Devin Leigh Department of History, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA, USA [email protected] Abstract Bryan Edwards’s The History of the British West Indies is a text well known to histori- ans of the Caribbean and the early modern Atlantic World. First published in 1793, the work is widely considered to be a classic of British Caribbean literature. This article introduces an unpublished first draft of Edwards’s preface to that work. Housed in the archives of the West India Committee in Westminster, England, this preface has never been published or fully analyzed by scholars in print. It offers valuable insight into the production of West Indian history at the end of the eighteenth century. In particular, it shows how colonial planters confronted the challenges of their day by attempting to wrest the practice of writing West Indian history from their critics in Great Britain. Unlike these metropolitan writers, Edwards had lived in the West Indian colonies for many years. He positioned his personal experience as being a primary source of his historical legitimacy. Keywords Bryan Edwards – West Indian history – eighteenth century – slavery – abolition Bryan Edwards’s The History, Civil and Commercial, of the British Colonies in the West Indies is a text well known to scholars of the Caribbean (Edwards 1793). First published in June of 1793, the text was “among the most widely read and influential accounts of the British Caribbean for generations” (V. -

The Global Visual Memory a Study of the Recognition and Interpretation of Iconic and Historical Photographs

The Global Visual Memory A Study of the Recognition and Interpretation of Iconic and Historical Photographs Het Mondiaal Visueel Geheugen Een studie naar de herkenning en interpretatie van iconische en historische foto’s (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof.dr. H.R.B.M. Kummeling, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op woensdag 19 juni 2019 des middags te 2.30 uur door Rutger van der Hoeven geboren op 4 juni 1974 te Amsterdam Promotor: Prof. dr. J. Van Eijnatten Table of Contents Abstract 2 Preface 3 Introduction 5 Objectives 8 Visual History 9 Collective Memory 13 Photographs as vehicles of cultural memory 18 Dissertation structure 19 Chapter 1. History, Memory and Photography 21 1.1 Starting Points: Problems in Academic Literature on History, Memory and Photography 21 1.2 The Memory Function of Historical Photographs 28 1.3 Iconic Photographs 35 Chapter 2. The Global Visual Memory: An International Survey 50 2.1 Research Objectives 50 2.2 Selection 53 2.3 Survey Questions 57 2.4 The Photographs 59 Chapter 3. The Global Visual Memory Survey: A Quantitative Analysis 101 3.1 The Dataset 101 3.2 The Global Visual Memory: A Proven Reality 105 3.3 The Recognition of Iconic and Historical Photographs: General Conclusions 110 3.4 Conclusions About Age, Nationality, and Other Demographic Factors 119 3.5 Emotional Impact of Iconic and Historical Photographs 131 3.6 Rating the Importance of Iconic and Historical Photographs 140 3.7 Combined statistics 145 Chapter 4. -

The Postcolonial North Atlantic Iceland, Greenland and the Faroe Islands

The Postcolonial North Atlantic Iceland, Greenland and the Faroe Islands Edited by Lill-Ann Körber and Ebbe Volquardsen Nordeuropa-Institut der Humboldt-Universität Berlin Table of Contents EBBE VOLQUARDSEN/LILL-ANN KÖRBER The Postcolonial North Atlantic: An Introduction WILLIAM FROST The Concept of the North Atlantic Rim; or, Questioning the North Iceland GUÐMUNDUR HÁLFDANARSON Iceland Perceived: Nordic, European or a Colonial Other? KRISTÍN LOFTSDÓTTIR Icelandic Identities in a Postcolonial Context ANN-SOFIE NIELSEN GREMAUD Iceland as Centre and Periphery: Postcolonial and Crypto-colonial Perspectives REINHARD HENNIG Postcolonial Ecology: An Ecocritical Reading of Andri Snær Magnason’s Dreamland: A Self-Help Manual for a Frightened Nation () HELGA BIRGISDÓTTIR Searching for a Home, Searching for a Language: Jón Sveinsson, the Nonni Books and Identity Formation DAGNÝ KRISTJÁNSDÓTTIR Guðríður Símonardóttir: The Suspect Victim of the Turkish Abductions in the th Century Faroe IslanDs BERGUR RØNNE MOBERG The Faroese Rest in the West: Danish-Faroese World Literature between Postcolonialism and Western Modernism 6 TABLE OF CONTENTS MALAN MARNERSDÓTTIR Translations of William Heinesen – a Post-colonial Experience CHRISTIAN REBHAN Postcolonial Politics and the Debates on Membership in the European Communities in the Faroe Islands (–) JOHN K. MITCHINSON Othering the Other: Language Decolonisation in the Faroe Islands ANNE-KARI SKARÐHAMAR To Be or Not to Be a Nation: Representations of Decolonisation and Faroese Nation Building in Gunnar Hoydal’s Novel Í havsins hjarta () Greenland BIRGIT KLEIST PEDERSEN Greenlandic Images and the Post-colonial: Is it such a Big Deal after all? CHRISTINA JUST A Short Story of the Greenlandic Theatre: From Fjaltring, Jutland, to the National Theatre in Nuuk, Greenland KIRSTEN THISTED Politics, Oil and Rock ‘n’ Roll. -

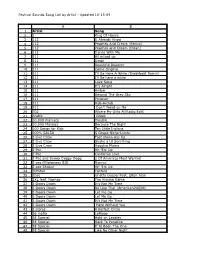

FS Master List-10-15-09.Xlsx

Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 2 1 King Of House 3 112 U Already Know 4 112 Peaches And Cream (Remix) 5 112 Peaches and Cream [Clean] 6 112 Dance With Me 7 311 All mixed up 8 311 Down 9 311 Beautiful Disaster 10 311 Come Original 11 311 I'll Be Here A While (Breakbeat Remix) 12 311 I'll Be here a while 13 311 Love Song 14 311 It's Alright 15 311 Amber 16 311 Beyond The Grey Sky 17 311 Prisoner 18 311 Rub-A-Dub 19 311 Don't Tread on Me 20 702 Where My Girls At(Radio Edit) 21 Arabic Greek 22 10,000 maniacs Trouble 23 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 24 100 Songs for Kids Ten Little Indians 25 100% SALSA S Grupo Niche-Lluvia 26 2 Live Crew Face Down Ass Up 27 2 Live Crew Shake a Lil Somthing 28 2 Live Crew Hoochie Mama 29 2 Pac Hit 'Em Up 30 2 Pac California Love 31 2 Pac and Snoop Doggy Dogg 2 Of Americas Most Wanted 32 2 pac f/Notorious BIG Runnin' 33 2 pac Shakur Hit 'Em Up 34 20thfox Fanfare 35 2pac Ghetto Gospel Feat. Elton John 36 2XL feat. Nashay The Kissing Game 37 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 38 3 Doors Down Be Like That (AmericanPieEdit) 39 3 Doors Down Let me Go 40 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 41 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 42 3 Doors Down Here Without You 43 3 Libras A Perfect Circle 44 36 mafia Lollipop 45 38 Special Hold on Loosley 46 38 Special Back To Paradise 47 38 Special If Id Been The One 48 38 Special Like No Other Night Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 49 38 Special Rockin Into The Night 50 38 Special Saving Grace 51 38 Special Second Chance 52 38 Special Signs Of Love 53 38 Special The Sound Of Your Voice 54 38 Special Fantasy Girl 55 38 Special Caught Up In You 56 38 Special Back Where You Belong 57 3LW No More 58 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 59 4 Non Blondes What's Up 60 50 Cent Just A Lil' Bit 61 50 Cent Window Shopper (Clean) 62 50 Cent Thug Love (ft. -

Historical Origins of the One-Drop Racial Rule in the United States

Historical Origins of the One-Drop Racial Rule in the United States Winthrop D. Jordan1 Edited by Paul Spickard2 Editor’s Note Winthrop Jordan was one of the most honored US historians of the second half of the twentieth century. His subjects were race, gender, sex, slavery, and religion, and he wrote almost exclusively about the early centuries of American history. One of his first published articles, “American Chiaroscuro: The Status and Definition of Mulattoes in the British Colonies” (1962), may be considered an intellectual forerunner of multiracial studies, as it described the high degree of social and sexual mixing that occurred in the early centuries between Africans and Europeans in what later became the United States, and hinted at the subtle racial positionings of mixed people in those years.3 Jordan’s first book, White over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550–1812, was published in 1968 at the height of the Civil Rights Movement era. The product of years of painstaking archival research, attentive to the nuances of the thousands of documents that are its sources, and written in sparkling prose, White over Black showed as no previous book had done the subtle psycho-social origins of the American racial caste system.4 It won the National Book Award, the Ralph Waldo Emerson Prize, the Bancroft Prize, the Parkman Prize, and other honors. It has never been out of print since, and it remains a staple of the graduate school curriculum for American historians and scholars of ethnic studies. In 2005, the eminent public intellectual Gerald Early, at the request of the African American magazine American Legacy, listed what he believed to be the ten most influential books on African American history. -

Cato, Roman Stoicism, and the American 'Revolution'

Cato, Roman Stoicism, and the American ‘Revolution’ Katherine Harper A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Arts Faculty, University of Sydney. March 27, 2014 For My Parents, To Whom I Owe Everything Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... i Abstract.......................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One - ‘Classical Conditioning’: The Classical Tradition in Colonial America ..................... 23 The Usefulness of Knowledge ................................................................................... 24 Grammar Schools and Colleges ................................................................................ 26 General Populace ...................................................................................................... 38 Conclusions ............................................................................................................... 45 Chapter Two - Cato in the Colonies: Joseph Addison’s Cato: A Tragedy .......................................... 47 Joseph Addison’s Cato: A Tragedy .......................................................................... 49 The Universal Appeal of Virtue ........................................................................... -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/24/2021 04:10:37AM Via Free Access 2 Pires, Strange and Mello Several Afro- and Indo-Guianese Populations

New West Indian Guide 92 (2018) 1–34 nwig brill.com/nwig The Bakru Speaks Money-Making Demons and Racial Stereotypes in Guyana and Suriname* Rogério Brittes W. Pires Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil [email protected] Stuart Earle Strange Yale-NUS College, Singapore [email protected] Marcelo Moura Mello Universidade Federal da Bahia, Salvador, Brazil [email protected] Abstract Throughout the Guianas, people of all ethnicities fear one particular kind of demonic spirit. Called baccoo in Guyana, bakru in coastal Suriname, and bakulu or bakuu among Saamaka and Ndyuka Maroons in the interior, these demons offer personal wealth in exchange for human life. Based on multisited ethnography in Guyana and Suriname, this paper analyzes converging and diverging conceptions of the “same” spirit among * Most of the research for this article was carried out by the authors during fieldwork for their Ph.D. dissertation.The research was financed byThe National Science Foundation,The Social Science Research Council, The Wenner Gren Foundation, and the University of Michigan’s Department of Anthropology (Stuart Strange); by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) and Museu Nacional’s Graduate Program in Social Anthro- pology, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (ufrj) (Marcelo Mello and Rogério Pires); and by a CNPq postdoctoral scholarship in the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (Rogério Pires). Previous versions of this article were presented twice in 2015 and once in 2017: in a seminar at Museu Nacional/ufrj, in a panel session at the American Anthropological Asso- ciation (aaa) meeting, and in a lecture at Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora (ufjf). -

Memorandum of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela on The

Memorandum of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela on the Application filed before the International Court of Justice by the Cooperative of Guyana on March 29th, 2018 ANNEX Table of Contents I. Venezuela’s territorial claim and process of decolonization of the British Guyana, 1961-1965 ................................................................... 3 II. London Conference, December 9th-10th, 1965………………………15 III. Geneva Conference, February 16th-17th, 1966………………………20 IV. Intervention of Minister Iribarren Borges on the Geneva Agreement at the National Congress, March 17th, 1966……………………………25 V. The recognition of Guyana by Venezuela, May 1966 ........................ 37 VI. Mixed Commission, 1966-1970 .......................................................... 41 VII. The Protocol of Port of Spain, 1970-1982 .......................................... 49 VIII. Reactivation of the Geneva Agreement: election of means of settlement by the Secretary-General of the United Nations, 1982-198371 IX. The choice of Good Offices, 1983-1989 ............................................. 83 X. The process of Good Offices, 1989-2014 ........................................... 87 XI. Work Plan Proposal: Process of good offices in the border dispute between Guyana and Venezuela, 2013 ............................................. 116 XII. Events leading to the communiqué of the UN Secretary-General of January 30th, 2018 (2014-2018) ....................................................... 118 2 I. Venezuela’s territorial claim and Process of decolonization -

Hdnet Schedule for Mon. January 30, 2012 to Sun. February 5, 2012

HDNet Schedule for Mon. January 30, 2012 to Sun. February 5, 2012 Monday January 30, 2012 3:30 PM ET / 12:30 PM PT 6:00 AM ET / 3:00 AM PT HDNet Fights Visions of New York City DREAM New Year! 2011 - Former PRIDE Heavyweight Champion Fedor Emelianenko meets New York in all its striking juxtapositions of nature and modern progress, geometry and geog- Olympic Judo Gold Medalist Satoshi Ishii. Shinya Aoki defends the DREAM Lightweight Title raphy - the harbor from Lady Liberty’s perspective to Central Park as the birds experience it. against Satoru Kitaoka. 7:00 AM ET / 4:00 AM PT 5:00 PM ET / 2:00 PM PT Cheers Prison Break Diane Meets Mom - Diane’s nervous about meeting Frasier’s mother Hester, who’s a Riots, Drills and the Devil - Michael’s ploy to buy some work time by prompting a cellblock renowned psychologist. Hester’s pleasant during dinner, but when Frasier leaves them alone, lockdown leads to a full-scale riot; Nick convinces Veronica that he really does want to help she threatens to kill Diane if she continues to interfere with her son’s life. her; and Kellerman hires an inmate to kill Lincoln. 7:30 AM ET / 4:30 AM PT 6:00 PM ET / 3:00 PM PT Cheers JAG An American Family - Carla’s ex-husband returns with his new bride, demanding custody of Offensive Action - In a P-3 Squadron over the Pacific Ocean, Cmdr. O’Neil hounds Lt. Kersey their oldest son. The normally feisty Carla shocks everyone at the bar when she agrees to the during a mission. -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

Pleksiglass Som Lokke Mat Og Mulighet Plexiglas As a Lure And

Pleksiglass som lokke mat og mulighet Pleksiglass som lokke mat og mulighet Plexiglas as a lure and Plexiglas potential By Liam Gillick Den britiske kunstneren Liam Gillick har gjerne The British artist Liam Gillick is often associated as a lure and blitt forbundet med den relasjonelle estetikken, with relational aesthetics, which emphasises the som la vekt på betrakteren som medskaper av ver- contribution of the viewer to an artwork and tends ket, og som ofte handlet om å tilrettelegge steder to focus on defining places and situations for social og situasjoner for sosial interaksjon. Men i mot- interaction. But in contrast to artists like Rirkrit setning til kunstnere som Rirkrit Tiravanija, som Tiravanija, who encourages audience-participation inviterte publikum til å samtale over et måltid, in a meal or a conversation, Gillick’s scenarios do gir ikke Gillicks scenarier inntrykk av å være laget not seem constructed for human activity. Instead, for menneskelig aktivitet. Installasjonene hans i his installations of Plexiglas and aluminium are potential pleksiglass og aluminium handlere snarere om concerned with the analysis of structures and types å analysere sosiale strukturer og organisasjons- of social organisation, and with the exploration of måter, og undersøke de romlige forutsetningene the spatial conditions for human interaction. Rec- for menneskelig interaksjon. Inspirert av hans ognising Gillick’s carefully considered relationship reflekterte forhold til materialene han jobber to the materials he uses, we invited him to write By med, ba vi ham skrive om sin interesse for pleksi- about his interest in Plexiglas, a material he has glass, et materiale han har arbeidet med i over 30 år.