John Bolton — Astronomer Extraordinary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quarterly Report, April 1

NATIONAL RADIO ASTRONOMY OBSERVATORY QUARTERLY REPORT April 1,1996 - June 30,1996 TABLE OF CONTENTS A. TELESCOPE USAGE .............................................................. 1 B. 140 FOOT OBSERVING PROGRAMS ................................................ 1 C. 12 METER TELESCOPE OBSERVING PROGRAMS .................................... 3 D. VERY LARGE ARRAY OBSERVING PROGRAMS ..................................... 7 E. VERY LONG BASELINE ARRAY OBSERVING PROGRAMS ........................... 15 F. SCIENCE HIGHLIGHTS ........................................................... 22 G. PUBLICATIONS ................................................................ 23 H. CHARLOTTESVILLE ELECTRONICS ............................................... 23 I. GREEN BANK ELECTRONICS .................................................... 25 J. TUCSON ELECTRONICS ......................................................... 26 K. SOCORRO ELECTRONICS........................................................ 27 L. COMPUTING AND AIPS.......................................................... 30 M . AIPS++ .................................................... .................... 32 N. GREEN BANK TELESCOPE PROJECT ............................................... 32 O. PERSONNEL .................................................................... 33 APPENDIX A. PREPRINTS A. TELESCOPE USAGE The following telescopes have been scheduled for research and maintenance in the following manner during the second quarter of 1996. 140 Foot 12 Meter VLA VLBA Scheduled Observing -

Bulletin No. 6 Issn 1520-3581

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII LIBRARY THE PACIFIC CIRCLE DECEMBER 2000 BULLETIN NO. 6 ISSN 1520-3581 PACIFIC CIRCLE NEW S .............................................................................2 Forthcoming Meetings.................................................. 2 Recent Meetings..........................................................................................3 Publications..................................................................................................6 New Members...............................................................................................6 IUHPS/DHS NEWS ........................................................................................ 8 PACIFIC WATCH....................................................................... 9 CONFERENCE REPORTS............................................................................9 FUTURE CONFERENCES & CALLS FOR PAPERS........................ 11 PRIZES, GRANTS AND FELLOWSHIPS........................... 13 ARCHIVES AND COLLECTIONS...........................................................15 BOOK AND JOURNAL NEWS................................................................ 15 BOOK REVIEWS..........................................................................................17 Roy M. MacLeod, ed., The ‘Boffins' o f Botany Bay: Radar at the University o f Sydney, 1939-1945, and Science and the Pacific War: Science and Survival in the Pacific, 1939-1945.................................. 17 David W. Forbes, ed., Hawaiian National Bibliography: 1780-1900. -

California Institute of Technology Catalog 1957-8

Bulletin of the California Institute of Technology Catalog 1957-8 PAS ADEN A, CALIFORNIA BULLETIN OF THE CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY VOLUME 66 NUMBER 3 The California Institute of Technology Bulletin is published quarterly Entered as Second Class Matter at the Post Office at Pasadena, California, under the Act of August 24, 1912 CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY A College, Graduate School, and Institute of Research in Science, Engineering, and the Humanities CATALOG 1957 -1958 PUBLISHED BY THE INSTITUTE SEPTEMBER, 1957 PASADENA, CALIFORNIA CONTENTS PART ONE. GENERAL INFORMATION PAGE Academic Calendar .............................. __ ...... _.. _._._. __ . __ . __ . __ .. _____ 11 Board of Trustees ..................... _...................... _... __ ....... _.. ______ .. 15 Trustee Committees ......................... _..... __ ._ .. _____ .. _........... _... __ .. 16 Administrative Officers of the Institute ..... ___ ........... _.. _.. _.... 18 Faculty Officers and Committees, 1957-58 ... __ .. __ ._ .. _... _......... _.... 19 Staff of Instruction and Research-Summary ._._ .. ___ ... ___ ._. 21 Staff of Instruction and Research .... _. __ .. __ .... _____ ._ .. __ .... _ 38 Fellows, Scholars and Assistants _.. _: __ ... _..._ ...... __ . __ .. _ 66 California Institute Associates .... _... _ ... _._ .. _... __ ... ._ .. __ .. _.. 79 Historical Sketch .................... _..... __ ........... __ .. __ ... _.... _... _.. ____ . 83 Educational Policies ...... _.. __ .... __ . 88 Industrial Associates ........_. __ 91 Industrial -

Newly Opened Correspondence Illuminates Einstein's Personal Life

CENTER FOR HISTORY OF PHYSICS NEWSLETTER Vol. XXXVIII, Number 2 Fall 2006 One Physics Ellipse, College Park, MD 20740-3843, Tel. 301-209-3165 Newly Opened Correspondence Illuminates Einstein’s Personal Life By David C. Cassidy, Hofstra University, with special thanks to Diana Kormos Buchwald, Einstein Papers Project he Albert Einstein Archives at the Hebrew University of T Jerusalem recently opened a large collection of Einstein’s personal correspondence from the period 1912 until his death in 1955. The collection consists of nearly 1,400 items. Among them are about 300 letters and cards written by Einstein, pri- marily to his second wife Elsa Einstein, and some 130 letters Einstein received from his closest family members. The col- lection had been in the possession of Einstein’s step-daughter, Margot Einstein, who deposited it with the Hebrew University of Jerusalem with the stipulation that it remain closed for twen- ty years following her death, which occurred on July 8, 1986. The Archives released the materials to public viewing on July 10, 2006. On the same day Princeton University Press released volume 10 of The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, con- taining 148 items from the collection through December 1920, along with other newly available correspondence. Later items will appear in future volumes. “These letters”, write the Ein- stein editors, “provide the reader with substantial new source material for the study of Einstein’s personal life and the rela- tionships with his closest family members and friends.” H. Richard Gustafson playing with a guitar to pass the time while monitoring the control room at a Fermilab experiment. -

Hr17903book Review

CSIRO PUBLISHING Historical Records of Australian Science, 2017, 28, 194–200 https://doi.org/10.1071/HR17903 Book Reviews Compiled by Peter Hobbins Department of History, The University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia. Email: [email protected] Neil Chambers (ed): Essays by scholars and curators including editor Neil Cham- Endeavouring Banks: Exploring bers, John Gascoigne, Jeremy Coote, Philip Hatfield and Anna Collections from the Agnarsdóttir—editor of Banks’ Iceland correspondence—take the Endeavour Voyage 1768–1771. text of the book into some surprising areas. Indeed, they lift it NewSouth Publishing: Sydney, from a catalogue to a substantial history. Collectively, they delve 2016. 304 pp., illus., into myriad thoughts and events associated with the voyage, from ISBN: 9781742235004 (HB), advice by the Admiralty regarding the transit of Venus to instruc- $69.99. tions regarding mapping, commerce and the possession of territory. But rather than telling a coherent story there is frequent repetition, The cover of Endeavouring Banks excessive detail, or superfluous information concerning intrigue and indicates the wide array of mate- minor characters. The contributors are deeply absorbed in their rial this book considers, includ- subject and the history of British exploration, sometimes at the ing subject matter only marginally expense of the general reader. related to its subtitle. In fact, the Items pictured include a model of the Endeavour, plans and 1773 satirical cartoon in which sketches, a nautical almanac, a Gregorian telescope, a quadrant, Joseph Banks appears as The Fly- a clock, a chart of the South Pacific, a hummingbird’s nest, shells, catching Macaroni—‘an amateur collector and dandy’—belies the botanical specimens, breadfruit, drums, canoes, spears, fish, belts, intense detail and seriousness with which the book deals with the pendants and instruments. -

From Radar to Radio Astronomy

John Bolton and the Nature of Discrete Radio Sources Thesis submitted by Peter Robertson BSc (Hons) Melbourne, MSc Melbourne 2015 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Agricultural, Computational and Environmental Sciences University of Southern Queensland ii Peter Robertson: ‘John Bolton and the Nature of Discrete Radio Sources’ Abstract John Bolton is regarded by many to be the pre-eminent Australian astronomer of his generation. In the late 1940s he and his colleagues discovered the first discrete sources of radio emission. Born in Sheffield in 1922 and educated at Cambridge University, in 1946 Bolton joined the Radiophysics Laboratory in Sydney, part of Australia’s Council for Scientific and Industrial Research. Radio astronomy was then in its infancy. Radio waves from space had been discovered by the American physicist Karl Jansky in 1932, followed by Grote Reber who mapped the emission strength across the sky, but very little was known about the origin or properties of the emission. This thesis will examine how the next major step forward was made by Bolton and colleagues Gordon Stanley and Bruce Slee. In June 1947, observing at the Dover Heights field station, they were able to show that strong radio emission from the Cygnus constellation came from a compact point-like source. By the end of 1947 the group had discovered a further five of these discrete radio sources, or ‘radio stars’ as they were known, revealing a new class of previously-unknown astronomical objects. By early 1949 the Dover Heights group had measured celestial positions for the sources accurately enough to identify three of them with known optical objects. -

The Discovery of Quasars and Its Aftermath

Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, 17(3), 267–282 (2014). THE DISCOVERY OF QUASARS AND ITS AFTERMATH K.I. Kellermann National Radio Astronomy Observatory, 520 Edgemont Road, Charlottesville, VA 22901, USA. Email: [email protected] Abstract: Although the extragalactic nature of quasars was discussed as early as 1960 by John Bolton and others it was rejected largely because of preconceived ideas about what appeared to be an unrealistically-high radio and optical luminosity. Following the 1962 observation of the occultations of the strong radio source 3C 273 with the Parkes Radio Telescope and the subsequent identification by Maarten Schmidt of an apparent stellar object, Schmidt recognized that the simple hydrogen line Balmer series spectrum implied a redshift of 0.16. Successive radio and optical measurements quickly led to the identification of other quasars with increasingly-large redshifts and the general, although for some decades not universal, acceptance of quasars as being by far the most distant and the most luminous objects in the Universe. However, due to an error in the calculation of the radio position, it appears that the occultation position played no direct role in the identification of 3C 273, although it was the existence of a claimed accurate occultation position that motivated Schmidt‘s 200-in Palomar telescope investi- gation and his determination of the redshift. Curiously, 3C 273, which is one of the strongest extragalactic sources in the sky, was first catalogued in 1959, and the 13th magnitude optical counterpart was observed at least as early as 1887. Since 1960, much fainter optical counterparts were being routinely identified, using accurate radio interferometer positions which were measured primarily at the Caltech Owens Valley Radio Observatory. -

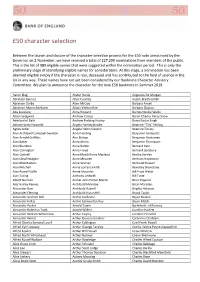

50 Character Selection

£50 character selection Between the launch and closure of the character selection process for the £50 note announced by the Governor on 2 November, we have received a total of 227,299 nominations from members of the public. This is the list of 989 eligible names that were suggested within the nomination period. This is only the preliminary stage of identifying eligible names for consideration: At this stage, a nomination has been deemed eligible simply if the character is real, deceased and has contributed to the field of science in the UK in any way. These names have not yet been considered by our Banknote Character Advisory Committee. We plan to announce the character for the new £50 banknote in Summer 2019. Aaron Klug Alister Hardy Augustus De Morgan Abraham Bennet Allen Coombs Austin Bradford Hill Abraham Darby Allen McClay Barbara Ansell Abraham Manie Adelstein Alliott Verdon Roe Barbara Clayton Ada Lovelace Alma Howard Barnes Neville Wallis Adam Sedgwick Andrew Crosse Baron Charles Percy Snow Aderlard of Bath Andrew Fielding Huxley Bawa Kartar Singh Adrian Hardy Haworth Angela Hartley Brodie Beatrice "Tilly" Shilling Agnes Arber Angela Helen Clayton Beatrice Tinsley Alan Archibald Campbell‐Swinton Anita Harding Benjamin Gompertz Alan Arnold Griffiths Ann Bishop Benjamin Huntsman Alan Baker Anna Atkins Benjamin Thompson Alan Blumlein Anna Bidder Bernard Katz Alan Carrington Anna Freud Bernard Spilsbury Alan Cottrell Anna MacGillivray Macleod Bertha Swirles Alan Lloyd Hodgkin Anne McLaren Bertram Hopkinson Alan MacMasters Anne Warner -

The National Radio Astronomy Observatory and Its Impact on US Radio Astronomy Historical & Cultural Astronomy

Historical & Cultural Astronomy Series Editors: W. Orchiston · M. Rothenberg · C. Cunningham Kenneth I. Kellermann Ellen N. Bouton Sierra S. Brandt Open Skies The National Radio Astronomy Observatory and Its Impact on US Radio Astronomy Historical & Cultural Astronomy Series Editors: WAYNE ORCHISTON, Adjunct Professor, Astrophysics Group, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, QLD, Australia MARC ROTHENBERG, Smithsonian Institution (retired), Rockville, MD, USA CLIFFORD CUNNINGHAM, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, QLD, Australia Editorial Board: JAMES EVANS, University of Puget Sound, USA MILLER GOSS, National Radio Astronomy Observatory, USA DUANE HAMACHER, Monash University, Australia JAMES LEQUEUX, Observatoire de Paris, France SIMON MITTON, St. Edmund’s College Cambridge University, UK CLIVE RUGGLES, University of Leicester, UK VIRGINIA TRIMBLE, University of California Irvine, USA GUDRUN WOLFSCHMIDT, Institute for History of Science and Technology, Germany TRUDY BELL, Sky & Telescope, USA The Historical & Cultural Astronomy series includes high-level monographs and edited volumes covering a broad range of subjects in the history of astron- omy, including interdisciplinary contributions from historians, sociologists, horologists, archaeologists, and other humanities fields. The authors are distin- guished specialists in their fields of expertise. Each title is carefully supervised and aims to provide an in-depth understanding by offering detailed research. Rather than focusing on the scientific findings alone, these volumes explain the context of astronomical and space science progress from the pre-modern world to the future. The interdisciplinary Historical & Cultural Astronomy series offers a home for books addressing astronomical progress from a humanities perspective, encompassing the influence of religion, politics, social movements, and more on the growth of astronomical knowledge over the centuries. -

The History of Early Low Frequency Radio Astronomy in Australia. 3: Ellis, Reber and the Cambridge Field Station Near Hobart

Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, 18(2), 177–189 (2015). THE HISTORY OF EARLY LOW FREQUENCY RADIO ASTRONOMY IN AUSTRALIA. 3: ELLIS, REBER AND THE CAMBRIDGE FIELD STATION NEAR HOBART Martin George, Wayne Orchiston National Astronomical Research Institute of Thailand, 191 Huay Kaew Road, Suthep District, Muang, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand, and University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, Queensland, Australia. Emails: [email protected]; [email protected] Bruce Slee CSIRO Astronomy and Space Sciences, Sydney, Australia. Email: [email protected] and Richard Wielebinski Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie, Bonn, Germany, and University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, Queensland, Australia. Email: [email protected] Abstract: Low frequency radio astronomy in Tasmania began with the arrival of Grote Reber to the State in 1954.1 After analysing ionospheric data from around the world, he concluded that Tasmania would be a very suitable place to carry out low frequency observations. Communications with Graeme Ellis in Tasmania, who had spent several years studying the ionosphere, led to a collaboration between the two in 1955 during which year they made observations at Cambridge, near Hobart. Their observations took place at four frequencies between 2.13 MHz and 0.52 MHz inclusive, with the results at the higher frequencies revealing a clear celestial component. Keywords: Australian low frequency radio astronomy, Tasmania, Grote Reber, Graeme Ellis, Cambridge. 1 INTRODUCTION galactic objects (see Bolton et al., 1949; Robert- son et al., 2014). The science of what would later be termed radio astronomy began in 1931 with the discovery by Reber‘s interest turned increasingly to low the American physicist Karl Jansky (1905–1950) frequency radio astronomy (Reber, 1977), but of radio-frequency radiation of celestial origin. -

Pdf (1960-1961)

CATALOG 1960-1961 CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY PASADENA' CALIFORNIA SEPTEMBER 1960 CONTENTS SECTION I. OFFICERS AND F ACUL TY PAGE Academic Calendar 4 Board of Trustees 9 Trustee Committees 10 Administrative Officers of the Institute 12 Faculty Officers and Committees, 1960-61 13 Staff of Instruction and Research 15 Fellows, Scholars, and Assistants 63 California Institute Associates 84 Industrial Associates 88 SECTION II. GENERAL INFORMATION Educational Policies 90 Historical Sketch 92 Industrial Relations Section 98 Buildings and Facilities 100 Study and Research at the California Institute 1. The Sciences 104 Astronomy 104 Biological Sciences 106 Chemistry and Chemical Engineering 108 Geological Sciences 110 Mathematics 113 Physics 115 2. Engineering 118 Aeronautics 120 Civil Engineering 122 Electrical Engineering 123 Engineering Science 125 Mechanical Engineering 125 Guggenheim Jet Propulsion Center 127 Hydrodynamics 127 3. The Humanities 130 Student Life 132 Air Force Reserve Officers Training Corps 138 2 SECTION III. INFORMATION AND REGULATIONS FOR THE GUIDANCE OF UNDERGRADUATE STUDENTS Requirements for Admission to Undergraduate Standing 139 Admission to Freshman Class 139 Admission to Upper Class by Transfer 146 The 3-2 Plan 149 Registration Regulations 150 Scholastic Grading and Requirements 152 Student Health and Physical Education 157 Expenses 160 Scholarships, Student Aid, and Prizes 164 SECTION IV. INFORMATION AND REGULATIONS FOR THE GUIDANCE OF GRADUATE STUDENTS General Regulations 176 Regulations Concerning Work for the Degree of Master of Science 178 Regulations Concerning Work for the Engineer's Degree 180 Regulations Concerning Work for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 182 Opportunities for Graduate and Scientific Work at the Institute 200 Graduate Fellowships, Scholarships, and Assistantships 201 Post-Doctoral Fellowships 203 Institute Guests 204 SECTION V. -

History of Astronomy in Australia: Big-Impact Astronomy from World War II Until the Lunar Landing (1945–1969)

galaxies Article History of Astronomy in Australia: Big-Impact Astronomy from World War II until the Lunar Landing (1945–1969) Alister W. Graham 1,* , Katherine H. Kenyon 1,†, Lochlan J. Bull 2,‡ , Visura C. Lokuge Don 3,§ and Kazuki Kuhlmann 4,k 1 Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing, Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn, VIC 3122, Australia 2 Horsham College, PO Box 508, Horsham, VIC 3402, Australia 3 Glen Waverley Secondary College, 39 O’Sullivan Rd, Glen Waverley, VIC 3150, Australia 4 Marcellin College, 160 Bulleen Road, Bulleen, VIC 3105, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] † Current address: Central Clinical School, The Alfred Centre, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC 3004, Australia. ‡ Current address: Department of Economics, Faculty of Business and Economics, University of Melbourne, Carlton, VIC 3053, Australia. § Current address: Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Monash University, Clayton, VIC 3800, Australia. k Current address: School of Engineering, RMIT, GPO Box 2476, Melbourne, VIC 3001, Australia. Abstract: Radio astronomy commenced in earnest after World War II, with Australia keenly en- gaged through the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research. At this juncture, Australia’s Citation: Graham, A.W.; Kenyon, K.H.; Bull, L.J.; Lokuge Don, V.C.; Commonwealth Solar Observatory expanded its portfolio from primarily studying solar phenomena Kuhlmann, K. History of Astronomy to conducting stellar and extragalactic research. Subsequently, in the 1950s and 1960s, astronomy in Australia: Big-Impact Astronomy gradually became taught and researched in Australian universities. However, most scientific publica- from World War II until the Lunar tions from this era of growth and discovery have no country of affiliation in their header information, Landing (1945–1969).