'Chief Princes and Owners of All': Native American Appeals to The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Television Has Long Upheld an Unspoken Rule: a Female Character May Be Beautiful Or Angry, but Never Both

PRETTY HURTS Television has long upheld an unspoken rule: A female character may be beautiful or angry, but never both. A handful of new shows prove that rules were made to be broken BY JULIA COOKE Shapely limbs swollen and wavering under longer dependent on men to be effective.” Woodley’s Jane runs hard and fast, flashing water, lipstick wiped off a pale mouth with a These days, injustice—often linked to the back to scenes of her rape and packing a gun in yellow sponge, blonde bangs caught in the zip- tangled ramifications of a heroine’s beauty— her purse to meet with a man who might be the per of a body bag: Kristy Guevara-Flanagan’s gives women license to take all sorts of juicy perpetrator. Their anger is nuanced, caused by 2016 short film What Happened to Her collects actions that are far more interesting than a range of situations, and on-screen they strug- images of dead women in a 15-minute montage killing. On Marvel’s Jessica Jones, it’s fury at gle to tame it into something else: self-defense, culled mostly from crime-based television dra- being raped and manipulated by the evil Kil- loyalty, grudges, power, career. mas. Throughout, men stand murmuring over grave that spurs the protagonist to become the The shift in representation aligns with the beautiful young white corpses. “You ever see righteously bitchy superhero she’s meant to increasing number of women behind cameras something like this?” a voice drawls. be. When her husband dumps her for his sec- in Hollywood. -

English, French, and Spanish Colonies: a Comparison

COLONIZATION AND SETTLEMENT (1585–1763) English, French, and Spanish Colonies: A Comparison THE HISTORY OF COLONIAL NORTH AMERICA centers other hand, enjoyed far more freedom and were able primarily around the struggle of England, France, and to govern themselves as long as they followed English Spain to gain control of the continent. Settlers law and were loyal to the king. In addition, unlike crossed the Atlantic for different reasons, and their France and Spain, England encouraged immigration governments took different approaches to their colo- from other nations, thus boosting its colonial popula- nizing efforts. These differences created both advan- tion. By 1763 the English had established dominance tages and disadvantages that profoundly affected the in North America, having defeated France and Spain New World’s fate. France and Spain, for instance, in the French and Indian War. However, those were governed by autocratic sovereigns whose rule regions that had been colonized by the French or was absolute; their colonists went to America as ser- Spanish would retain national characteristics that vants of the Crown. The English colonists, on the linger to this day. English Colonies French Colonies Spanish Colonies Settlements/Geography Most colonies established by royal char- First colonies were trading posts in Crown-sponsored conquests gained rich- ter. Earliest settlements were in Virginia Newfoundland; others followed in wake es for Spain and expanded its empire. and Massachusetts but soon spread all of exploration of the St. Lawrence valley, Most of the southern and southwestern along the Atlantic coast, from Maine to parts of Canada, and the Mississippi regions claimed, as well as sections of Georgia, and into the continent’s interior River. -

(King Philip's War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial

Connecticut Unscathed: Victory in The Great Narragansett War (King Philip’s War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Major Jason W. Warren, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin Jr., Advisor Alan Gallay, Kristen Gremillion Peter Mansoor, Geoffrey Parker Copyright by Jason W. Warren 2011 Abstract King Philip’s War (1675-1676) was one of the bloodiest per capita in American history. Although hostile native groups damaged much of New England, Connecticut emerged unscathed from the conflict. Connecticut’s role has been obscured by historians’ focus on the disasters in the other colonies as well as a misplaced emphasis on “King Philip,” a chief sachem of the Wampanoag groups. Although Philip formed the initial hostile coalition and served as an important leader, he was later overshadowed by other sachems of stronger native groups such as the Narragansetts. Viewing the conflict through the lens of a ‘Great Narragansett War’ brings Connecticut’s role more clearly into focus, and indeed enables a more accurate narrative for the conflict. Connecticut achieved success where other colonies failed by establishing a policy of moderation towards the native groups living within its borders. This relationship set the stage for successful military operations. Local native groups, whether allied or neutral did not assist hostile Indians, denying them the critical intelligence necessary to coordinate attacks on Connecticut towns. The English colonists convinced allied Mohegan, Pequot, and Western Niantic warriors to support their military operations, giving Connecticut forces a decisive advantage in the field. -

The Current Status and Issues Surrounding Native Title in Regional Australia

284 Australasian Journal of Regional Studies, Vol. 24, No 3, 2018 NEW DIMENSIONS IN LAND TENURE – THE CURRENT STATUS AND ISSUES SURROUNDING NATIVE TITLE IN REGIONAL AUSTRALIA Jude Mannix PhD Candidate, Science and Engineering Faculty, School of Civil Engineering and Built Environment, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Queensland, 4000, Australia. Email: [email protected]. Michael Hefferan Emeritus Professor, c/- Science and Engineering Faculty, School of Civil Engineering and Built Environment, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Queensland, 4000, Australia. Email: [email protected]. ABSTRACT: The acquisition and use of real property is fundamental to practically all types of resource and infrastructure projects. The success of those activities is based, in no small way, on the reliability of the underlying tenure and land management systems operating across all Australian states and territories. Against that background, however, the historic Mabo (1992) decision gave recognition to Indigenous land rights and the subsequent enactment of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth.) (NTA) ushered in an emerging and complex new aspect of property law. While receiving wide political and community support, these changes have had a significant effect on those long-established tenure systems. Further, it has only been over time, as diverse property dealings have been encountered, that the full implications of the new legislation and its operations have become clear. Regional areas are more likely to encounter native title issues than are urban environments due, in part, to the presence of large scale agricultural and pastoral tenures and of significant areas of un-alienated crown land, where native title may not have been extinguished. -

Scriptedpifc-01 Banijay Aprmay20.Indd 2 10/03/2020 16:54 Banijay Rights Presents… Bäckström the Hunt for a Killer We Got This Thin Ice

Insight on screen TBIvision.com | April/May 2020 Television e Interview Virtual thinking The Crown's Andy Online rights Business Harries on what's companies eye next for drama digital disruption TBI International Page 10 Page 12 pOFC TBI AprMay20.indd 1 20/03/2020 20:25 Banijay Rights presents… Bäckström The Hunt For A Killer We Got This Thin Ice Crime drama series based on the books by Leif GW Persson Based on a true story, a team of police officers set out to solve a How hard can it be to solve the world’s Suspense thriller dramatising the burning issues of following the rebellious murder detective Evert Bäckström. sadistic murder case that had remained unsolved for 16 years. most infamous unsolved murder case? climate change, geo-politics and Arctic exploitation. Bang The Gulf GR5: Into The Wilderness Rebecka Martinsson When a young woman vanishes without a trace In a brand new second season, a serial killer targets Set on New Zealand’s Waiheke Island, Detective Jess Savage hiking the famous GR5 trail, her friends set out to Return of the riveting crime thriller based on a group of men connected to a historic sexual assault. investigates cases while battling her own inner demons. solve the mystery of her disappearance. the best-selling novels by Asa Larsson. banijayrights.com ScriptedpIFC-01 Banijay AprMay20.indd 2 10/03/2020 16:54 Banijay Rights presents… Bäckström The Hunt For A Killer We Got This Thin Ice Crime drama series based on the books by Leif GW Persson Based on a true story, a team of police officers set out to solve a How hard can it be to solve the world’s Suspense thriller dramatising the burning issues of following the rebellious murder detective Evert Bäckström. -

Bibliography of A.F. Pollard's Writings

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF A.F. POLLARD'S WRITINGS This bibliography is not quite complete: we omitted mention of very short book reviews, and we have not been able to trace every one of Pollard's contributions to the T.L.S. As to his letters to the Editor of The Times, we only mentioned the ones consulted on behalf of our research. There has been no separate mention of Pollard's essays from the years 1915-1917, collectedly published in The Commonwealth at War (1917). The Jesuits in Poland, Oxford, 1892. D.N.B. vol. 34: Lucas, Ch. (1769-1854); Luckombe, Ph. (d. 1803); Lydiat, Th. (1572-1646). vol. 35: Macdonald, A. (1834-1886); Macdonell, A. (1762-1840); Macegan, O. (d. 1603); Macfarlan, W. (d. 1767); Macha do, R. (d. lSI I?); Mackenzie, W.B. (1806-1870); Maclean, Ch. (1788-1824); Magauran, E. (IS48-IS93); Maguire, H. (d. 1600); Maguire, N. (1460-1512). vol. 36: Manderstown, W. (ISIS-IS40); Mansell, F. (1579-166S); Marshall, W. (d. 153S); Martin, Fr. (1652-1722); Martyn, R. (d. 1483); Mascall,R. (d. 1416); Mason,]. (1503-1566); Mason, R. (1571-1635). Review :].B. Perkins, France under the Regency, London, 1892. E.H.R. 8 (1893), pp. 79 1-793. 'Sir Edward Kelley' in Lives oj Twelve Bad Men, ed. Th. Seccombe, London, 1894, pp. 34-54· BIBLIOGRAPHY OF A.F. POLLARD'S WRITINGS 375 D.N.B. vol. 37: Matcham, G. (1753-1833); Maunsfield, H. (d. 1328); Maurice, Th. (1754-1824); Maxfield, Th. (d. 1616); May, W. (d. 1560); Mayart, S. (d. 1660?); Mayers, W.F. -

A Brief History of Native Americans in Essex, Connecticut

A Brief History of Native Americans in Essex, Connecticut by Verena Harfst, Essex Table of Contents Special Thanks and an Appeal to the Community 3 - 4 Introduction 5 The Paleo-Indian Period 6 - 7 The Archaic Period 7 - 10 The Woodland Period 11 – 12 Algonquians Settle Connecticut 12 - 14 Thousands of Years of Native American Presence in Essex 15 - 19 Native American Life in the Essex Area Shortly Before European Arrival 19 - 23 Arrival of the Dutch and the English 23 - 25 Conflict and Defeat 25 - 28 The Fate of the Nihantic 28 - 31 Postscript 31 Footnotes 31 - 37 2 Special Thanks and an Appeal to the Community This article contributes to an ongoing project of the Essex Historical Society (EHS) and the Essex Land Trust to celebrate the history of the Falls River in south central Connecticut. This modest but lovely watercourse connects the three communities comprising the Town of Essex, wending its way through Ivoryton, Centerbrook and Essex Village, where it flows into North Cove and ultimately the main channel of the Connecticut River a few miles above Long Island Sound. Coined “Follow the Falls”, the project is being conducted largely by volunteers devoted to their beautiful town and committed to helping the Essex Historical Society and the Essex Land Trust achieve their missions. This article by a local resident focuses on the history of the Indigenous People of Essex. The article is based on interviews the author conducted with a number of archaeologists and historians as well as reviews of written materials readily accessible on the history of Native Americans in New England. -

ROYAL—All but the Crown!

The emily Dickinson inTernaTional socieTy Volume 21, Number 2 November/December 2009 “The Only News I know / Is Bulletins all Day / From Immortality.” emily dickinson in20ternation0al so9ciety general meeting EMILY DICKINSON: ROYA L — all but the Crown! Queen Without a Crown July –August , , Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada eDis 2009 annual meeTing Eleanor Heginbotham with Beefeater Guards Emily with Beefeater Guards Suzanne Juhasz, Jonnie Guerra, and Cris Miller with Beefeater Guards Cindy MacKenzie and Emily Special Tea Cake Paul Crumbley, EDIS president and Cindy MacKenzie, organizer of the 2009 Annual Meeting Georgie Strickland, former editor of the Bulletin Bill and Nancy Pridgen, EDIS members George Gleason, EDIS member and Jane Wald, executive director of the Emily Dickinson Museum Jane Eberwein, Gudrun Grabher, Vivian Pollak, Martha Ackmann and Ann Romberger at banquet Group in front of the Provincial Government House and Eleanor Heginbotham at banquet Cover Photo Courtesy of Emily Seelbinder Photos Courtesy of Eleanor Heginbotham and Georgie Strickland I n Th I s Is s u e Page 3 Page 12 Page 33 F e a T u r e s r e v I e w s 3 Queen Without a Crown: EDIS 2009 19 New Publications Annual Meeting By Barbara Kelly, Book Review Editor By Douglas Evans 24 Review of Jed Deppman, Trying to Think with Emily Dickinson 6 Playing Emily or “the welfare of my shoes” Reviewed by Marianne Noble By Barbara Dana 25 Review of Elizabeth Oakes, 9 Teaching and Learning at the The Luminescence of All Things Emily Emily Dickinson Museum Reviewed by Janet -

Mapmaking in England, Ca. 1470–1650

54 • Mapmaking in England, ca. 1470 –1650 Peter Barber The English Heritage to vey, eds., Local Maps and Plans from Medieval England (Oxford: 1525 Clarendon Press, 1986); Mapmaker’s Art for Edward Lyman, The Map- world maps maker’s Art: Essays on the History of Maps (London: Batchworth Press, 1953); Monarchs, Ministers, and Maps for David Buisseret, ed., Mon- archs, Ministers, and Maps: The Emergence of Cartography as a Tool There is little evidence of a significant cartographic pres- of Government in Early Modern Europe (Chicago: University of Chi- ence in late fifteenth-century England in terms of most cago Press, 1992); Rural Images for David Buisseret, ed., Rural Images: modern indices, such as an extensive familiarity with and Estate Maps in the Old and New Worlds (Chicago: University of Chi- use of maps on the part of its citizenry, a widespread use cago Press, 1996); Tales from the Map Room for Peter Barber and of maps for administration and in the transaction of busi- Christopher Board, eds., Tales from the Map Room: Fact and Fiction about Maps and Their Makers (London: BBC Books, 1993); and TNA ness, the domestic production of printed maps, and an ac- for The National Archives of the UK, Kew (formerly the Public Record 1 tive market in them. Although the first map to be printed Office). in England, a T-O map illustrating William Caxton’s 1. This notion is challenged in Catherine Delano-Smith and R. J. P. Myrrour of the Worlde of 1481, appeared at a relatively Kain, English Maps: A History (London: British Library, 1999), 28–29, early date, no further map, other than one illustrating a who state that “certainly by the late fourteenth century, or at the latest by the early fifteenth century, the practical use of maps was diffusing 1489 reprint of Caxton’s text, was to be printed for sev- into society at large,” but the scarcity of surviving maps of any descrip- 2 eral decades. -

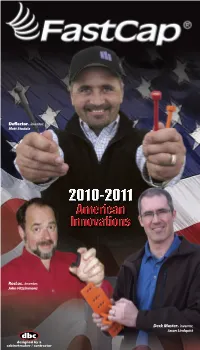

Fastcap 21-30

DeflectorTM inventor, Matt Stodola RocLocTM inventor, John Fitzsimmons Deck MasterTM inventor, Jason Lindquist dbc designed by a cabinetmaker / contractor PRO Tools VLRQDO RIHV JUDG SU H Artisan Accents TM JUHDWSULFH & Mortise Tool Turn of the century craftsmanship with the tap of a hammer. Available in three sizes: 5/16”, 3/8” and 2”, create a beautiful ebony pinned look with the Mortise ToolTM and Artisan AccentsTM. Combining the two allows you to create the look of Greene & Greene furniture in a fraction of the time. Everyone will think you spent hours using ebony pins, flush cut saws and meticulously sanding. “Stop The StruggleTM” 1. Identify where the pin needs to go and tap with the Mortise ToolTM to make the Get the “Greene & Greene” look Accent divots. 2. Install a trim screw, if using one (it is not necessary; the Accents can simply be decorative). 3. Align the Artisan AccentTM in the divots, tap with a hammer until the edge of the Artisan AccentTM is flush with the edge of the wood and you are done! Note: Apply a dab of 2P-10TM Jël under the Artisan AccentTM for a permanent hold. Fast & simple! The 2” Artisan Chisel on an air hammer leaves a perfect outline for the Accents. The Artisan Accent tools are intended for use in real wood Great for... applications. Not recommended • Furniture • Beams for use on man-made material. • Cabinets • Rafters • Trim • Decks • and more! A Pocket Chisel creates square corners for the accent 2” 5 ⁄16” A small dab of 2P-10 Jël in the corners locks the Accent in place 3 ⁄8” Patent Pending Description Part Number USD Artisan Accents (50 pc) 5/16” ARTISAN ACCENT 5/16 $5.00 Mortise Tool (5/16”) MORTISE TOOL 5/16 $20.00 Artisan Accents (50 pc) 3/8” ARTISAN ACCENT 3/8 $5.00 Mortise Tool (3/8”) MORTISE TOOL 3/8 $20.00 Inventor, Artisan Accents (10 pc) 2” ARTISAN ACCENT 2 $9.99 Jeff Marholin Artisan Chisel 2” ARTISAN CHISEL 2 $59.99 A fi nished professional look dbc designed by a cabinetmaker www.fastcap.com 21 PRO Tools TM *Four corners shown Screw the Ass. -

The Role of the Channel Islands in the Development and Application of Norman Law During the Late Middle Ages and Early Modern Period

THE JERSEY & GUERNSEY LAW REVIEW 2018 THE ROLE OF THE CHANNEL ISLANDS IN THE DEVELOPMENT AND APPLICATION OF NORMAN LAW DURING THE LATE MIDDLE AGES AND EARLY MODERN PERIOD Tim Thornton Although attention has been paid to the impact of continental Norman law on the Channel Islands, the impact of the experience and practice of the islands themselves on Norman law, more generally, has not been taken into consideration. This is despite the fact that it is increasingly clear that, far from being isolated from developments in continental Normandy, at the social, economic and ecclesiastical level after 1204 the islands were directly involved in exchanges in many contexts. In this paper the role of the islands is assessed in the practice and development of Norman law in the period from the fifteenth century to the seventeenth century. 1 In this short paper I intend to consider briefly the history of Norman law in its relation to the Islands, and more specifically the place and influence of the Islands within the wider Norman legal context. The role of Norman customary law in Jersey and Guernsey has been extensively discussed. Terrien’s commentary on the Ancienne Coutume was published in 1574 and was reprinted in 1578 and 1654. It was in Guernsey’s case the reference point for the limited degree of codification achieved through the Approbation des Loix in 1583, while Jersey remained more straightforwardly able to refer to what ironically in same year was published on the mainland as the Coutume Reformée. Even after the end of the 16th century, Island law across both Bailiwicks continued to develop with reference to the practice of the mainland, including the Coutume Reformée, through the commentators on it, Basnage, Bérault, Godefroy, and D’Aviron being the main ones in the period before the 18th century. -

Uncas Leap Falls: a Convergence of Cultures

Uncas Leap Falls: A Convergence of Cultures Site Feasibility Study August 29, 2012 This page intentionally left blank Uncas Leap Falls: A Convergence of Cultures Prepared for the City of Norwich & The Mohegan Tribe August 29, 2012 Study Team: Goderre & Associates, LLC with Economic Stewardship, Inc. Hutton Associates, Inc. Gibble Norden Champion Brown Consulting Engineers, Inc. Nelson Edwards Company Architects, LLC Archeological and Historic Services, Inc. 1492: Columbus arrives in the Americas Front cover illustration of Uncas provided by the Mohegan Tribe 1598: Uncas is born Historical Timeline 1620: Pilgrims arrive 1634 – 1638: Pequot War 1654: John Casor is first legally recognized slave in the US 1659: Norwich founded 1675 – 1678: King Philip’s War 1683: Uncas’ death 1741: Benedict Arnold is born 1754: French Indian War begins 1763: French Indian War ends 1775: American Revolutionary War begins 1776: Signing of the Declaration of Independence 1783: American Revolutionary War ends 1863: President Lincoln signs the Emancipation Proclamation 2012: Norwich Casts the Freedom Bell Uncas Leap Falls: A Convergence of Cultures Site Feasibility Study August 29, 2012 2 Uncas Leap Falls: A Convergence of Cultures TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Overview.............................................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Cultures Converge ...............................................................................................................