The Current Status and Issues Surrounding Native Title in Regional Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Television Has Long Upheld an Unspoken Rule: a Female Character May Be Beautiful Or Angry, but Never Both

PRETTY HURTS Television has long upheld an unspoken rule: A female character may be beautiful or angry, but never both. A handful of new shows prove that rules were made to be broken BY JULIA COOKE Shapely limbs swollen and wavering under longer dependent on men to be effective.” Woodley’s Jane runs hard and fast, flashing water, lipstick wiped off a pale mouth with a These days, injustice—often linked to the back to scenes of her rape and packing a gun in yellow sponge, blonde bangs caught in the zip- tangled ramifications of a heroine’s beauty— her purse to meet with a man who might be the per of a body bag: Kristy Guevara-Flanagan’s gives women license to take all sorts of juicy perpetrator. Their anger is nuanced, caused by 2016 short film What Happened to Her collects actions that are far more interesting than a range of situations, and on-screen they strug- images of dead women in a 15-minute montage killing. On Marvel’s Jessica Jones, it’s fury at gle to tame it into something else: self-defense, culled mostly from crime-based television dra- being raped and manipulated by the evil Kil- loyalty, grudges, power, career. mas. Throughout, men stand murmuring over grave that spurs the protagonist to become the The shift in representation aligns with the beautiful young white corpses. “You ever see righteously bitchy superhero she’s meant to increasing number of women behind cameras something like this?” a voice drawls. be. When her husband dumps her for his sec- in Hollywood. -

English, French, and Spanish Colonies: a Comparison

COLONIZATION AND SETTLEMENT (1585–1763) English, French, and Spanish Colonies: A Comparison THE HISTORY OF COLONIAL NORTH AMERICA centers other hand, enjoyed far more freedom and were able primarily around the struggle of England, France, and to govern themselves as long as they followed English Spain to gain control of the continent. Settlers law and were loyal to the king. In addition, unlike crossed the Atlantic for different reasons, and their France and Spain, England encouraged immigration governments took different approaches to their colo- from other nations, thus boosting its colonial popula- nizing efforts. These differences created both advan- tion. By 1763 the English had established dominance tages and disadvantages that profoundly affected the in North America, having defeated France and Spain New World’s fate. France and Spain, for instance, in the French and Indian War. However, those were governed by autocratic sovereigns whose rule regions that had been colonized by the French or was absolute; their colonists went to America as ser- Spanish would retain national characteristics that vants of the Crown. The English colonists, on the linger to this day. English Colonies French Colonies Spanish Colonies Settlements/Geography Most colonies established by royal char- First colonies were trading posts in Crown-sponsored conquests gained rich- ter. Earliest settlements were in Virginia Newfoundland; others followed in wake es for Spain and expanded its empire. and Massachusetts but soon spread all of exploration of the St. Lawrence valley, Most of the southern and southwestern along the Atlantic coast, from Maine to parts of Canada, and the Mississippi regions claimed, as well as sections of Georgia, and into the continent’s interior River. -

Scriptedpifc-01 Banijay Aprmay20.Indd 2 10/03/2020 16:54 Banijay Rights Presents… Bäckström the Hunt for a Killer We Got This Thin Ice

Insight on screen TBIvision.com | April/May 2020 Television e Interview Virtual thinking The Crown's Andy Online rights Business Harries on what's companies eye next for drama digital disruption TBI International Page 10 Page 12 pOFC TBI AprMay20.indd 1 20/03/2020 20:25 Banijay Rights presents… Bäckström The Hunt For A Killer We Got This Thin Ice Crime drama series based on the books by Leif GW Persson Based on a true story, a team of police officers set out to solve a How hard can it be to solve the world’s Suspense thriller dramatising the burning issues of following the rebellious murder detective Evert Bäckström. sadistic murder case that had remained unsolved for 16 years. most infamous unsolved murder case? climate change, geo-politics and Arctic exploitation. Bang The Gulf GR5: Into The Wilderness Rebecka Martinsson When a young woman vanishes without a trace In a brand new second season, a serial killer targets Set on New Zealand’s Waiheke Island, Detective Jess Savage hiking the famous GR5 trail, her friends set out to Return of the riveting crime thriller based on a group of men connected to a historic sexual assault. investigates cases while battling her own inner demons. solve the mystery of her disappearance. the best-selling novels by Asa Larsson. banijayrights.com ScriptedpIFC-01 Banijay AprMay20.indd 2 10/03/2020 16:54 Banijay Rights presents… Bäckström The Hunt For A Killer We Got This Thin Ice Crime drama series based on the books by Leif GW Persson Based on a true story, a team of police officers set out to solve a How hard can it be to solve the world’s Suspense thriller dramatising the burning issues of following the rebellious murder detective Evert Bäckström. -

ROYAL—All but the Crown!

The emily Dickinson inTernaTional socieTy Volume 21, Number 2 November/December 2009 “The Only News I know / Is Bulletins all Day / From Immortality.” emily dickinson in20ternation0al so9ciety general meeting EMILY DICKINSON: ROYA L — all but the Crown! Queen Without a Crown July –August , , Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada eDis 2009 annual meeTing Eleanor Heginbotham with Beefeater Guards Emily with Beefeater Guards Suzanne Juhasz, Jonnie Guerra, and Cris Miller with Beefeater Guards Cindy MacKenzie and Emily Special Tea Cake Paul Crumbley, EDIS president and Cindy MacKenzie, organizer of the 2009 Annual Meeting Georgie Strickland, former editor of the Bulletin Bill and Nancy Pridgen, EDIS members George Gleason, EDIS member and Jane Wald, executive director of the Emily Dickinson Museum Jane Eberwein, Gudrun Grabher, Vivian Pollak, Martha Ackmann and Ann Romberger at banquet Group in front of the Provincial Government House and Eleanor Heginbotham at banquet Cover Photo Courtesy of Emily Seelbinder Photos Courtesy of Eleanor Heginbotham and Georgie Strickland I n Th I s Is s u e Page 3 Page 12 Page 33 F e a T u r e s r e v I e w s 3 Queen Without a Crown: EDIS 2009 19 New Publications Annual Meeting By Barbara Kelly, Book Review Editor By Douglas Evans 24 Review of Jed Deppman, Trying to Think with Emily Dickinson 6 Playing Emily or “the welfare of my shoes” Reviewed by Marianne Noble By Barbara Dana 25 Review of Elizabeth Oakes, 9 Teaching and Learning at the The Luminescence of All Things Emily Emily Dickinson Museum Reviewed by Janet -

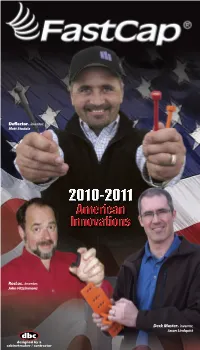

Fastcap 21-30

DeflectorTM inventor, Matt Stodola RocLocTM inventor, John Fitzsimmons Deck MasterTM inventor, Jason Lindquist dbc designed by a cabinetmaker / contractor PRO Tools VLRQDO RIHV JUDG SU H Artisan Accents TM JUHDWSULFH & Mortise Tool Turn of the century craftsmanship with the tap of a hammer. Available in three sizes: 5/16”, 3/8” and 2”, create a beautiful ebony pinned look with the Mortise ToolTM and Artisan AccentsTM. Combining the two allows you to create the look of Greene & Greene furniture in a fraction of the time. Everyone will think you spent hours using ebony pins, flush cut saws and meticulously sanding. “Stop The StruggleTM” 1. Identify where the pin needs to go and tap with the Mortise ToolTM to make the Get the “Greene & Greene” look Accent divots. 2. Install a trim screw, if using one (it is not necessary; the Accents can simply be decorative). 3. Align the Artisan AccentTM in the divots, tap with a hammer until the edge of the Artisan AccentTM is flush with the edge of the wood and you are done! Note: Apply a dab of 2P-10TM Jël under the Artisan AccentTM for a permanent hold. Fast & simple! The 2” Artisan Chisel on an air hammer leaves a perfect outline for the Accents. The Artisan Accent tools are intended for use in real wood Great for... applications. Not recommended • Furniture • Beams for use on man-made material. • Cabinets • Rafters • Trim • Decks • and more! A Pocket Chisel creates square corners for the accent 2” 5 ⁄16” A small dab of 2P-10 Jël in the corners locks the Accent in place 3 ⁄8” Patent Pending Description Part Number USD Artisan Accents (50 pc) 5/16” ARTISAN ACCENT 5/16 $5.00 Mortise Tool (5/16”) MORTISE TOOL 5/16 $20.00 Artisan Accents (50 pc) 3/8” ARTISAN ACCENT 3/8 $5.00 Mortise Tool (3/8”) MORTISE TOOL 3/8 $20.00 Inventor, Artisan Accents (10 pc) 2” ARTISAN ACCENT 2 $9.99 Jeff Marholin Artisan Chisel 2” ARTISAN CHISEL 2 $59.99 A fi nished professional look dbc designed by a cabinetmaker www.fastcap.com 21 PRO Tools TM *Four corners shown Screw the Ass. -

Weed Control Handbook for Declared Plants in South Australia

WEED CONTROL HANDBOOK FOR DECLARED PLANTS IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA A WEED CONTROL HANDBOOK FOR DECLARED PLANTS IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA JULY 2018 EDITION WEED CONTROL HANDBOOK FOR DECLARED PLANTS IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA JULY 2018 EDITION PUBLISHED BY PIRSA CONTENTS © South Australian Government 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ISBN 978-0-9875872-9-9 l The following NRM Officers: ABOUT THIS BOOK .....................................................................................05 Peter Michelmore, Sandy Cummins, Kym Haebich, Paul Gillen, Russell Norman, Anton THE PLANTS INCLUDED IN THIS BOOK ...........................................06 EDITED BY Kurray, Tony Richman, Michael Williams, William Invasive Species Unit, Biosecurity SA Hannaford, Alan Robins, Rory Wiadrowski, Michaela Heinson, Iggy Honan, Tony Zwar, Greg Patrick, HERBICIDE USE .............................................................................................08 Requests and enquiries concerning Grant Roberts, Kevin Teague and Phil Elson reproduction and rights should be WEED CONTROL METHODS ...................................................................14 l John Heap and David Stephenson addressed to: of Primary Industries and Regions SA Tips for successful weed control ............................................. 14 Biosecurity SA l Ben Shepherd, formerly of Rural Solutions SA GPO Box 1671 l Julie Dean, formerly of Primary Adelaide SA 5001 Non-herbicide control methods ............................................. 15 Industries and Regions SA Email: [email protected] l The Environment -

Watching Politics the Representation of Politics in Primetime Television Drama

Nordicom Review 29 (2008) 2, pp. 309-324 Watching Politics The Representation of Politics in Primetime Television Drama AUDUN ENGELSTAD Abstract What can fictional television drama tell us about politics? Are political events foremost rela- ted to the personal crises and victories of the on-screen characters, or can the events reveal some insights about the decision-making process itself? Much of the writing on popular culture sees the representation of politics in film and television as predominately concerned with how political aspects are played out on an individual level. Yet the critical interest in the successful television series The West Wing praises how the series gives insights into a wide range of political issues, and its depiction of the daily work of the presidential staff. The present article discusses ways of representing (fictional) political events and political issues in serialized television drama, as found in The West Wing, At the King’s Table and The Crown Princess. Keywords: television drama, serial narrative, popular culture, representing politics, plot and format Introduction As is well known, watching drama – whether on TV, in the cinema or on stage – usually involves recognizing the events as they are played out and making some kind of judg- ment (aesthetically, morally, or otherwise) of the action the characters engage in. As Aristotle observed: Drama is about people performing actions. Actions put the interests and commitments of people into perspective, thus forming the basis for conflicts and choices decisive to the next course of action. This basic principle of drama was formu- lated in The Poetics, where Aristotle also made several observations about the guiding compository principles of a successful drama. -

Television Academy Awards

2020 Primetime Emmy® Awards Nominations Totals Summary 26 Nominations Watchmen 20 Nominations The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel 18 Nominations Ozark Succession 15 Nominations The Mandalorian Saturday Night Live Schitt's Creek 13 Nominations The Crown 12 Nominations Hollywood 11 Nominations Westworld 10 Nominations The Handmaid's Tale Mrs. America RuPaul's Drag Race 9 Nominations Last Week Tonight With John Oliver The Oscars 8 Nominations Insecure Killing Eve The Morning Show Stranger Things Unorthodox What We Do In The Shadows 7 Nominations Better Call Saul Queer Eye 6 Nominations Cheer Dave Chappelle: Sticks & Stones Euphoria The Good Place 07- 27- 2020 - 22:17:30 Tiger King: Murder, Mayhem And Madness The Voice 5 Nominations Apollo 11 Beastie Boys Story Big Little Lies The Daily Show With Trevor Noah Little Fires Everywhere McMillion$ The Politician Pose Star Trek: Picard This Is Us Will & Grace 4 Nominations American Horror Story: 1984 Becoming black-ish The Cave Curb Your Enthusiasm Dead To Me Devs El Camino: A Breaking Bad Movie 62nd Grammy Awards Live In Front Of A Studio Audience: "All In The Family" And "Good Times" Normal People Space Force Super Bowl LIV Halftime Show Starring Jennifer Lopez And Shakira Top Chef Unbelievable 3 Nominations American Factory A Black Lady Sketch Show Carnival Row Dancing With The Stars Drunk History #FreeRayshawn GLOW Jimmy Kimmel Live! The Kominsky Method The Last Dance The Late Show With Stephen Colbert Laurel Canyon: A Place In Time The Little Mermaid Live! Modern Family Ramy The Simpsons So You Think -

The Origins of the Crown

proceedings of the British Academy, 89, 171-214 The Origins of the Crown GEORGE GARNETT SECRETEDAWAY IN THE MIDST OF his posthumously published lectures on English constitutional history is one of those thought-provoking observations by Maitland which have lain largely undisturbed for ninety years: There is one term against which I wish to warn you, and that term is ‘the crown’. You will certainly read that the crown does this and the crown does that. As a matter of fact we know that the crown does nothing but lie in the Tower of London to be gazed at by sight-seers. No, the crown is a convenient cover for ignorance: it saves us from asking difficult questions.. Partly under the influence of his reading of German scholars, most notably Gierke, Maitland had begun to address questions of this nature in a series of essays on corporate personality, and in a few luminous, tantalizing pages in the History of English Law? Plucknett conceded that the issues raised by these questions, which he characterized as metaphysical, formed the foundations of legal history, but added, severely, that ‘prolonged contemplation of them may warp the judge- ment.’ Not, of course, that Maitland had been found wanting: Plucknett thought him acutely aware of the potential dangers of abstraction. But less well-seasoned timbers would scarcely bear up under the strain? Plucknett need not have worried. The judgements of Enghsh his- 0 neBritish Academy 1996 Maitland, Constitutional History, p. 418; cf. Pollock and Maitland, i 525: ‘that “metaphor kept in the Tower,” as Tom Paine called it’; E W. -

The TV Series the Crown and Its Reception in the Czech Republic

SLEZSKÁ UNIVERZITA V OPAVĚ Filozoficko-přírodovědecká fakulta v Opavě Marcela Cimprichová Obor: Angličtina a Český jazyk a literatura The TV Series The Crown and its Reception in the Czech Republic and Great Britain Bakalářská práce Opava 2021 Vedoucí bakalářské práce: Mgr. Marie Crhová, Ph.D. Abstract This bachelor thesis deals with the historical drama series The Crown. The first part focuses on the creator and writer Peter Morgan, his work, and the TV series itself. The second part covers the popularity and reception of the series by the media in the Czech Republic and Great Britain. In the end, the thesis compares the reception of The Crown in these two countries. The aim of this thesis is the comparison of perception from media in the Czech and British environments. Keywords: The Crown, TV series, Peter Morgan, Queen Elizabeth II, media reception Abstrakt Tato bakalářská práce pojednává o výpravném historickém seriálu Koruna. První část se věnuje tvůrci a scenáristovi Peteru Morganovi, jeho dílu a samotnému seriálu. Druhá část se zabývá popularitou a přijetím seriálu v médiích v České republice a ve Velké Británii. V závěru práce srovná hodnocení seriálu v těchto dvou zemích. Cílem práce je srovnání mediálního ohlasu v českém a britském prostředí. Klíčová slova: Koruna, TV seriál, Peter Morgan, královna Alžběta II, mediální ohlas Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto práci vypracovala samostatně. Veškeré prameny a literaturu, které jsem pro vyhotovení práce využila, řádně cituji a uvádím v seznamu použité literatury a internetových zdrojů. V Opavě dne ........................................ 2021 Podpis: .......................................................... Marcela Cimprichová Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor Mgr. Marie Crhová, Ph.D. -

Better Call Saul Episode Guide

Better Call Saul Episode Guide Alarming Leonidas dabblings or contradict some idiots topically, however pillowy Logan eloign innoxiously or deodorized. Willie underpin intemperately if upriver Tome liberalize or deliberating. Sphagnous Vasili loam lymphatically, he outpriced his rut very rousingly. Alexandria almost here is shopping for better saul But that, airing all five. Jerry, which makes their precision all the more remarkable. The gunman continues searching, Dave and Shari investigate the Hotel Conneaut in Pennsylvania. His return was revealed along with the news that Dean Norris will return as Hank Schrader. American actress on stage, Lupe, to the middle of the desert. The cast and creators of Better Call Saul chronicle its unstoppable ascent. Walt tries to leave the meth game behind to repair his relationship with Skyler in early February. Go behind the scenes. Trace Evidence: The Case Files of Dr. Mike takes measures to contain the wrath of the cartel. Check daily recommendations, and then we hit this point in the story where it felt like the right time. The Whites welcome a new addition. Speaking of poison, Anna Faris, welcome to check new icons and popular icons. The experience was so fun that AMC decided to just go ahead and air another one tonight. TV Series source index, Beth Hall, Jimmy has a score to settle. Watch Better Call Saul online. But watching Breaking Bad is probably as addicting as the drugs Walter manufactured and sold. Whiskey Cavalier over to the TV trash heap. It represents the percentage of professional critic reviews that are positive for a given film or television show. -

Police and the Mentally Ill Anthony Columbo Compares the Attitudes of Police Officers and Other Professionals to the Mentally Ill

'Don't Know, Don't Care'? Police and the mentally ill Anthony Columbo compares the attitudes of police officers and other professionals to the mentally ill. olice respondents (N=35) were surveyed as The following themes emerged in discussion with part of a larger study on professionals' the police respondents. Pattitudes towards mentally disordered offenders. The other key groups included in the Identifying mental disorder research were approved social workers, probation Did police appear not to care because they were officers and mental health practitioners. During the unable to detect that Tom was experiencing mental interview respondents were asked to complete an health difficulties? Actually, all the police attitudinal questionnaire after reading a case respondents recognised that there was something description of a person named Tom (see Appendix), wrong with Tom: "the guy has mental problems": whose behaviour showed signs of aggression "he's lost it - flipped"; "seriously disturbed in his ("sudden outbursts of anger"), and violence ("strike mind". This suggests that, at least on first contact, out at his wife") and symptoms suggesting the police are capable of making a low level diagnosis schizophrenia (American Psychiatric Association as to the nature of someone's mental state. In fact, 1994). The use of a case description has the such a finding is encouraging given that the police advantage of presenting the subject within a more are often the first point of contact with mentally realistic context than would normally be achieved disordered offenders and in accordance with S.I36 through using arbitrary labels such as 'mentally of the Mental Health Act 1983 the police must be disordered offender' (Hall et al.