Elections and Administrative Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Australian Electoral Commission Perspective

Chapter Two Current Issues and Recent Cases on Electoral Law — The Australian Electoral Commission perspective Paul Pirani Before turning to an analysis of recent cases dealing with the Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) (hereafter: the Electoral Act), I need to give a quick outline of exactly what is the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) and its role. What is the Australian Electoral Commission? The AEC conducts elections under a range of legislation. The main role for the AEC is the conduct of federal elections under the Electoral Act and referendums under the Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Act 1984 (Referendum Act). However, in addition, the AEC conducts fee-for-service elections under the authority contained in sections 7A and 7B of the Electoral Act, industrial elections under the Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Act 2009, protected action ballots under the Fair Work Act 2009 and elections for the Torres Strait Regional Authority under the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Regional Authority Act 2005. The AEC itself comprises three persons, the Chairperson (the Honourable Peter Heerey, QC), the non-judicial member (the Chief Statistician, Brian Pink) and the Electoral Commissioner (Ed Killesteyn) (see section 6 of the Electoral Act). The AEC is not a body corporate. As a matter of law, the AEC is not a legal entity that is separate from the Commonwealth of Australia. This means that the AEC is not a body corporate and is unable to sue and be sued or to enter into contracts in its own right. This is despite what was stated in the Commonwealth Parliament in 1983 when major reforms to Australia’s electoral laws took place with the amendments to the Electoral Act to establish the AEC. -

Government Gazette

11221 Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Number 164 Friday, 23 December 2005 Published under authorityNew by Government South Wales Advertising and Information New South Wales LEGISLATIONNew South Wales New South Wales ProclamationsNew South Wales New South Wales Proclamation Proclamation Proclamationunder the underProclamation the New South Wales Childrenunder the and Young Persons (Care and Protection) Amendment under the ChildrenActunderProclamation 2005 the and No 93Young Persons (Care and Protection) Amendment ActChildren 2005 andNo 93Young Persons (Care and Protection) Amendment ChildrenActunder 2005 the and No 93Young Persons (Care and Protection) Amendment Act 2005 No 93 Children and Young Persons (Care and Protection) Amendment, Governor ProclamationActI, Professor 2005 MarieNo 93 Bashir AC, Governor of the State of New South Wales,, Governor with the advice of the Executive Council, and in pursuanceJAMES of section JACOB 2 of the SPIGELMAN, Children, Governor and I, Professor Marie Bashir AC, Governor of the State of New South Wales,, Governor with the underI,Young Professor thePersons Marie (Care Bashir and AC, ByProtection) Governor Deputation ofAmendment the from State Her of Act NewExcellency 2005 South, do, Wales, the by ,Governor Governor thiswith mythe adviceI, Professor of the Marie Executive Bashir Council, AC, Governor and in pursuanceof the State of of section New South2 of the Wales, Children with and the YoungI,adviceProclamation, Professor ofPersons the Marie Executive appoint (Care Bashir 31 andCouncil, DecemberAC, Protection) Governor and 2005 in pursuance of Amendmentas the the State day of ofon sectionAct Newwhich 2005 South2 thatof, thedo, ActWales, Children bycommences thiswith and mythe adviceYoungexcept ofSchedulePersons the Executive 1(Care [1] and Council,and [4]–[8]. -

VOTES and PROCEEDINGS No

1980-81-82 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 81 TUESDAY, 23 MARCH 1982 I The House met, at 1.45 p.m., pursuant to adjournment. Mr Speaker (the Right Honourable Sir Billy Snedden) took the Chair, and read Prayers. 2 RETURN TO WRIT-LOWE DIVISION: Mr Speaker announced that he had received a return to the writ which he had issued on 25 January 1982 for the election of a Member to serve for the Electoral Division of Lowe, in the State of New South Wales, to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of the Right Honourable Sir William McMahon, G.C.M.G., C.H., and that, by the endorsement on the writ, it was certified that Michael John Maher had been elected. 3 OATH OF ALLEGIANCE BY MEMBER: Michael John Maher was introduced, and made and subscribed the oath of allegiance required by law. 4 MINISTERIAL ARRANGEMENTS: Mr Fraser (Prime Minister) informed the House that, during the respective absences abroad of Mr Anthony (Minister for Trade and Resources) and Mr Newman (Minister for Administrative Services), Mr Sinclair (Minister for Communications) was acting as Minister for Trade and Resources and Mr Thomson (Minister for Science and Technology) was acting as Minister for Administrative Services. 5 QUESTIONS: Questions without notice were asked. 6 PAPERS: The following papers were presented: By command of His Excellency the Governor-General: Canberra Commercial Development Authority-Sth Annual Report, for year 1979-80. Registrar of Motor Vehicle Dealers, Australian Capital Territory-4th Annual Report, for year 1980-81. -

Elliot & Sochacki Submission

•"28/07/2805 13:50 02-66841344 ELLIOTT & SOCHACKI 01 02 66841344 ELLIOT & SOCHACKI SUBMISSION 173 Our Ref; Andrew Sochacki: gm Joint Standing Commttte on Electoral Matters Sybmlislon No. ,.,.JL3,,sa Date Received 28 July, 2005 Seerettry BY FACSIMILE; 6277 ATTENTION: MR STEVE DYER Inquiry Secretary Parliament of Australia Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Sir, RE: ENQUIRY INTO THE 2004 FEDERAL ELECTION JOINT STANDING COMMITTEE ON ELECTORAL MATTERS HEARING AT TWEED HEADS ON 7 JULY 2005 EVIDENCE AND SUBMISSIONS MADE BY MR ANDREW N. SOCHACKI, CHAIRMAN - RICHMOND ELECTORATE COUNCIL FOR AND ON BEHALF OF THE NATIONALS ThanJk you for your letter of 22nd instant received 27th instant annexed to which was the Transcript. I have perused the Transcript and it appears to be in order, As previously promised and as you have requested enclosed please find is my previously prepared but only partly delivered at the enquiry, submission vis a vis the issues affecting the Federal Division of Richmond and perhaps indirectly the whole of Australia. The submission consists of six (6) pages together with some statistics pertaining to the Federal Division of Richmond and the Federal Division of Page. Should you have any questions about my complete written submission, please do not hesitate and contact me in due course. Sincerely Yours, - -. Andrew N. Sochacki PERSONALISED PROFESSIONAL COMMITMENT TEL (02) 06 842 842 FAX (02) 86 841 344 [email protected] soucrroR - ANDREW N, SOCHACKI 97/99 STUART STREET, MULLUMBIMBY -

Proposed Redistribution of the New South Wales Into Electoral Divisions

Proposed redistribution of New South Wales into electoral divisions OCTOBER 2015 Report of the Redistribution Committee for New South Wales Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 Feedback and enquiries Feedback on this report is welcome and should be directed to the contact officer. Contact officer National Redistributions Manager Roll Management Branch Australian Electoral Commission 50 Marcus Clarke Street Canberra ACT 2600 PO Box 6172 Kingston ACT 2604 Telephone: 02 6271 4411 Fax: 02 6215 9999 Email: [email protected] AEC website www.aec.gov.au Accessible services Visit the AEC website for telephone interpreter services in 18 languages. Readers who are deaf or have a hearing or speech impairment can contact the AEC through the National Relay Service (NRS): – TTY users phone 133 677 and ask for 13 23 26 – Speak and Listen users phone 1300 555 727 and ask for 13 23 26 – Internet relay users connect to the NRS and ask for 13 23 26 ISBN: 978-1-921427-38-1 © Commonwealth of Australia 2015 © State of New South Wales 2015 The report should be cited as Redistribution Committee for the New South Wales, Proposed redistribution of New South Wales into electoral divisions. 15_0526 The Redistribution Committee for New South Wales (the Committee) has completed its proposed redistribution of New South Wales into 47 electoral divisions. In developing and considering the impacts of the redistribution proposal, the Committee has satisfied itself that the proposed boundaries meet the requirements of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Electoral Act). The Committee unanimously agreed on the boundaries and names of the proposed electoral divisions, and recommends its redistribution proposal for New South Wales. -

Richmond-Tweed Family History Society

Richmond-Tweed Family History Society Inc - Catalogue Call No Title Author Nv-1Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Aston Nv-2Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Ballarat Nn-15Y 1984 Electoral roll : Division of Banks Nn-14Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Barton Nt-1Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Bass Nv-3Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Batman Nv-4Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Bendigo Nn-12Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Berowra Nn-11Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Blaxland Ns-4Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Boothby Nq-1Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Bowman Nt-2Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Braddon Nn-16Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Bradfield Nw-1Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Brand Nq-2Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Brisbane Nv-5Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Bruce Nv-6Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Burke Nv-7Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Calwell Nw-2Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Canning Nq-3Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Capricornia Nv-8Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Casey Nn-17Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Charlton Nn-23Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Chifley Nv-9Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Chisholm 06 October 2012 Page 1 of 167 Call No Title Author Nn-22Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Cook Nv-10Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Corangamite Nv-11Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Corio Nw-3Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Cowan Nn-21Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Cowper Nn-20Y 1984 Electoral roll : division of Cunningham -

Proposed Template

CALENDAR YEAR 2013 SENATE ORDER ON DEPARTMENTAL AND AGENCY CONTRACTS LISTING RELATING TO THE PERIOD 1 JANUARY 2013 TO 31 DECEMBER 2013 Pursuant to the Senate Order on departmental and agency contracts the following table sets out contracts entered into by the Australian Electoral Commission which provide for a consideration to the value of $100 000 or more and which: (a) have not been fully performed as at 31 December 2013 or (b) have been entered into during the 12 months prior to 31 December 2013. Most of the Contracts listed contain confidentiality provisions of a general nature that are designed to protect the confidential information of the parties that may be obtained or generated in carrying out the contract. The reasons for including such clauses include: Ordinary commercial prudence that requires protection of trade secrets, proprietary information and the like; and/or Protection of other Commonwealth material and personal information. Contractor Subject matter Amount of Commencement Anticipated Whether Whether Reasons for consideration Date End Date contract contract confidentiality contains contains ‘Other provisions requirements requiring the of parties to confidentiality’. maintain (Y/N) confidentiality of any of its provisions (Y/N) 695 BURKE ROAD PROPERTY LEASE – 302,000 30/06/2013 29/06/2017 N N N/A PTY LTD DIVISIONS OF KOOYONG/HIGGINS ABNOTE PRINTING BINDING 424,986 03/01/2006 05/08/2014 N N N/A AUSTRALASIA PTY PACKAGING & LTD DELIVERY: REFERENCE ROLLS/ CERTIFIED LISTS ACHERMANN PROPERTY LEASE – 512,000 01/10/2011 30/09/2014 -

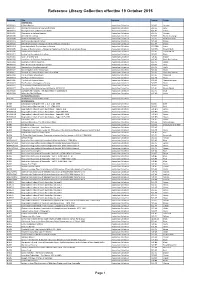

Reference Library Collection Effective 19 October 2015

Reference Library Collection effective 19 October 2015 Accession Title Location Format Colour ABORIGINAL ABOR-010 A Black Reality Australian Collection S/C B5 Orange ABOR-017 Aboriginal Reserves in New South Wales Australian Collection S/C A5 Grey ABOR-013 Aboriginal Sites of New South Wales Australian Collection S/C A4 Cream ABOR-007 Aborigines in Colonial Society Australian Collection S/C A5 Orange ABOR-006 After the Dreaming Australian Collection S/C B6 Brown & orange ABOR-008 Aliens in Arnhem Land Australian Collection S/C A5 Blue & Orange ABOR-015 Australian Aboriginal Culture Australian Collection S/C A5 Brown ABOR-003 Before White Man - Aboriginal life in prehistoric Australia Australian Collection S/C A4 Brown ABOR-014 First Australians, Our heritage in Stamps Australian Collection S/C ODD Sepia ABOR-005 Guests of the Governor - Aboriginal Residents of the First Government House Australian Collection S/C B5 L Blue & Multi ABOR-001 Indigenous Australians Australian Collection S/C A5 Cream/Multi ABOR-019 Justice for Aboriginal Australians Australian Collection S/C B5 Black ABOR-011 Koori, A Will to Win Australian Collection H/C B5 Brown ABOR-009 Landrights, A Christian Perspective Australian Collection H/C A5 Black Red Yellow ABOR-018 Outcasts in White Australia Australian Collection S/C A5 White ABOR-016 Race Relations in North Queensland Australian Collection S/C B5 Grey ABOR-020 Recognition: The Way Forward Australian Collection S/C A5 Multi ABOR-022 Reconciliation at the Crossroads Australian Collection S/C A4 Multi ABOR-012 -

Legislative Council- PROOF Page 1

Wednesday, 6 June 2018 Legislative Council- PROOF Page 1 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Wednesday, 6 June 2018 The PRESIDENT (The Hon. John George Ajaka) took the chair at 11:00. The PRESIDENT read the prayers. Documents SYDNEY STADIUMS POWERHOUSE MUSEUM OUT-OF-HOME CARE SERVICES Correspondence The PRESIDENT: On Tuesday 5 June 2018 the House ordered that should the Leader of the Government fail to table certain documents in compliance with the resolution of the House the Leader of the Government is to attend in his place at the table on the next sitting day at the conclusion of the prayers being read to explain his reasons for continued non-compliance with: (a) the resolution of the House of 15 March 2018 relating to Sydney Stadiums in respect of certain documents, including business cases; (b) the resolution of the House of 12 April 2018 relating to the preliminary and final business cases for the relocation of the Powerhouse Museum from Ultimo to Parramatta; and (c) the resolution of the House of 17 May 2018 relating to the final report and final draft report of the independent review of the out-of-home care system in New South Wales. I call on the Clerk of the Parliaments to table correspondence received from the Deputy Secretary, Cabinet and Legal, Department of Premier and Cabinet. The CLERK: I table correspondence from Ms Karen Smith, Deputy Secretary, Cabinet and Legal, Department of Premier and Cabinet, dated 6 June 2018, in relation to the order of the House advising that: After considering advice from the Crown Solicitor, a copy of which is enclosed, I advise that there are no further documents for production. -

Answers to Questions on Notice Budget Estimates 2014-15

Senate Finance and Public Administration Legislation Committee ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS ON NOTICE BUDGET ESTIMATES 2014-15 Finance Portfolio Department/Agency: All Outcome/Program: General Topic: Staffing profile Senator: Ludwig Question reference number: F210 Type of question: Written Date set by the committee for the return of answer: Friday, 11 July 2014 Number of pages: 16 Question: 1. What is the current staffing profile of the department/agency? 2. Provide a list of staffing numbers, broken down by classification level, division, home base location (including town/city and state). Answer: As at 31 May 2014: Department/ Response Agency Finance 1. The staffing profile for the Department was 1430 ongoing, 11 non-going and 331 casual employees. 2. Refer to Attachment A. Australian 1. As at 31 May 2014: Electoral Commission Full time staff Part time staff Casual staff Total 680 176 1780 2636 This table excludes contractors and temporary election/by-election staff. 2. Refer Attachment B. ComSuper 1 - 2. All ComSuper staff are located in Canberra, ACT. ComSuper’s staffing profile, by classification and branch, is at Attachment C. Commonwealth 1. There were 75 staff employed being full-time 66, part time 7, and casual 2. This Superannuation represented a Full Time Equivalent of 71.77 staff. Corporation 2. CSC does not use classification levels for its employees. The staff divisions are as follows: • CEO Office 2; • Board Services 2; 1 Department/ Response Agency • Chief Investment Officer 17; • Member & Employer Services 14.87; • General Counsel 3; • Finance & Risk 16.23; • Operations 16.67. Staff are located as follows: • Sydney, NSW – 20; • Canberra, ACT – 53; • Brisbane, QLD – 1; • Melbourne, VIC – 1. -

Book Catalogue 2020

RICHMOND RIVER HISTORICAL SOCIETY CATALOGUE OF HOLDINGS (Books) Based on New Classification Compiled by Margaret Henderson R = Reference Book X = Held in secured area (Stack) ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- The Arts [A] ARTS DIRECTORY: Northern Rivers Region of N.S.W.: January 1987 A/ARTS/N Prepared by the Northern Rivers Regional Organisation of Councils and The Arts Council of NSW Lismore, the compilers, 1987. 137p, 30cm. 1. The Arts – North Coast District. 2. Crafts – North Coast District #2009.84.3 VISARTS 85: a guide to visual arts on the Far North Coast NSW: A/ARTS/S (a)-(b) a directory of artists and craftspeople living and working on the Far North Coast, compiled by Vivienne Sigley and Jan Renkin. Lismore, Richmond-Tweed Regional Library and Lismore Regional Art Gallery, 1985. ISBN 0-949459-05-4 Note: Includes portraits of artists and their work. 1. The Arts – North Coast District. 2. Crafts – North Coast District. I. Sigley, Vivienne, comp. II. Renkin, Jan, jt. comp. #1992.30.1 #2009.62.1 The ART of Ancient Egypt. 709.01/ART A/EGYP Vienna, Phaidon Press, 1936. 1.Egypt, Ancient – Art. [Reference: Ancient Egypt] 2.Art and Architecture – Egypt, Ancient. [Reference: Architecture]. #1955.200.1 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Galleries/Museums/Collections [A.8] RUSHBROOK, Rebecca 708/LISM/R A.8/GALL/L Ebb and flow: a history of Lismore Regional Gallery, 1954-2004, 50th anniversary. Lismore, the Gallery, 2004. 1. Lismore Regional Art Gallery – History. 2. Art Galleries – Lismore. I. Title: 50th anniversary: ebb and flow… #2004.117.1 MUSEUMS AUSTRALIA 708/MUSE A.8/MUSE/A Caring for our culture; national guidelines for museums, galleries and keeping places. -

Library Catalogue Effective March 2014

Library Catalogue effective March 2014 Accession Title Location Format Colour ABORIGINAL ABOR-010 A Black Reality Australian Collection S/C B5 Orange ABOR-017 Aboriginal Reserves in New South Wales Australian Collection S/C A5 Grey ABOR-013 Aboriginal Sites of New South Wales Australian Collection S/C A4 Cream ABOR-007 Aborigines in Colonial Society Australian Collection S/C A5 Orange ABOR-006 After the Dreaming Australian Collection S/C B6 Brown & orange ABOR-008 Aliens in Arnhem Land Australian Collection S/C A5 Blue & Orange ABOR-015 Australian Aboriginal Culture Australian Collection S/C A5 Brown ABOR-003 Before White Man - Aboriginal life in prehistoric Australia Australian Collection S/C A4 Brown ABOR-014 First Australians, Our heritage in Stamps Australian Collection S/C ODD Sepia ABOR-005 Guests of the Governor - Aboriginal Residents of the First Government House Australian Collection S/C B5 L Blue & Multi ABOR-001 Indigenous Australians Australian Collection S/C A5 Cream/Multi ABOR-019 Justice for Aboriginal Australians Australian Collection S/C B5 Black ABOR-011 Koori, A Will to Win Australian Collection H/C B5 Brown ABOR-009 Landrights, A Christian Perspective Australian Collection H/C A5 Black Red Yellow ABOR-018 Outcasts in White Australia Australian Collection S/C A5 White ABOR-016 Race Relations in North Queensland Australian Collection S/C B5 Grey ABOR-020 Recognition: The Way Forward Australian Collection S/C A5 Multi ABOR-022 Reconciliation at the Crossroads Australian Collection S/C A4 Multi ABOR-012 Survival, A History