Director's Early Films

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alternative Digital Movies As Malaysian National Cinema A

Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Hsin-ning Chang April 2017 © 2017 Hsin-ning Chang. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema by HSIN-NING CHANG has been approved for Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts by Erin Schlumpf Visiting Assistant Professor of Film Studies Elizabeth Sayrs Interim Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT CHANG, HSIN-NING, Ph.D., April 2017, Interdisciplinary Arts Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema Director of dissertation: Erin Schlumpf This dissertation argues that the alternative digital movies that emerged in the early 21st century Malaysia have become a part of the Malaysian national cinema. This group of movies includes independent feature-length films, documentaries, short and experimental films and videos. They closely engage with the unique conditions of Malaysia’s economic development, ethnic relationships, and cultural practices, which together comprise significant understandings of the nationhood of Malaysia. The analyses and discussions of the content and practices of these films allow us not only to recognize the economic, social, and historical circumstances of Malaysia, but we also find how these movies reread and rework the existed imagination of the nation, and then actively contribute in configuring the collective entity of Malaysia. 4 DEDICATION To parents, family, friends, and cats in my life 5 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor, Prof. -

SPRING 2012 FSCP 81000--Aesthetics of Film

SPRING 2012 FSCP 81000--Aesthetics of Film, Professor Edward Miller, Monday, 4:14-8:15p.m., Room C-419, 3 credits [17259] Cross listed with THEA 71400, ART 79400 & MALS 77100 Ever since the Lumiere Brother's train arrived at the station, film has been concerned with its own mechanics and meanings and the ways in which film not only captures the moment but transforms it, creating an impact upon its audience with distinct aesthetics. This course highlights the self-referentiality of film and argues that a central aspect of the cinematic enterprise is the depiction of the filmmaking environment itself through the "meta- film." Using this emphasis as an entry into aesthetics, the course involves students in graduate- level film discourse by providing them with a thorough understanding of the concepts that are needed to perform a detailed formal analysis. The course's main text is the ninth edition of Bordwell and Thompson's Film Art (2009) and the book is used to examine such key topics as narrative and nonnarrative forms, mise-en-scene, composition, cinematography, camera movement, set design/location, color, duration, editing, sound/music, and genre. In addition, we read key sections of Robert Stam's Reflexivity in Film and Literature: From Don Quixote to Jean-Luc Godard (1992), Christopher Ames' Movies about Movies: Hollywood Revisited (1997), Nöth & Bishara's Self-Reference in the Media (2007), John Thornton Caldwell's Production Culture: Industrial Reflexivity and Critical Practice in Film & Television (2008), and Lisa Konrath's Metafilms: Forms and Functions of Self-Reflexivity in Postmodern Film (2010) in order to strengthen our understanding of the connections between aesthetics and reflexivity. -

Collection Adultes Et Jeunesse

bibliothèque Marguerite Audoux collection DVD adultes et jeunesse [mise à jour avril 2015] FILMS Héritage / Hiam Abbass, réal. ABB L'iceberg / Bruno Romy, Fiona Gordon, Dominique Abel, réal., scénario ABE Garage / Lenny Abrahamson, réal ABR Jamais sans toi / Aluizio Abranches, réal. ABR Star Trek / J.J. Abrams, réal. ABR SUPER 8 / Jeffrey Jacob Abrams, réal. ABR Y a-t-il un pilote dans l'avion ? / Jim Abrahams, David Zucker, Jerry Zucker, réal., scénario ABR Omar / Hany Abu-Assad, réal. ABU Paradise now / Hany Abu-Assad, réal., scénario ABU Le dernier des fous / Laurent Achard, réal., scénario ACH Le hérisson / Mona Achache, réal., scénario ACH Everyone else / Maren Ade, réal., scénario ADE Bagdad café / Percy Adlon, réal., scénario ADL Bethléem / Yuval Adler, réal., scénario ADL New York Masala / Nikhil Advani, réal. ADV Argo / Ben Affleck, réal., act. AFF Gone baby gone / Ben Affleck, réal. AFF The town / Ben Affleck, réal. AFF L'âge heureux / Philippe Agostini, réal. AGO Le jardin des délices / Silvano Agosti, réal., scénario AGO La influencia / Pedro Aguilera, réal., scénario AGU Le Ciel de Suely / Karim Aïnouz, réal., scénario AIN Golden eighties / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Hotel Monterey / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Jeanne Dielman 23 quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE La captive / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Les rendez-vous d'Anna / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE News from home / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario, voix AKE De l'autre côté / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI Head-on / Fatih Akin, réal, scénario AKI Julie en juillet / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI L'engrenage / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI Solino / Fatih Akin, réal. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

43E Festival International Du Film De La Rochelle Du 26 Juin Au 5 Juillet 2015 Le Puzzle Des Cinémas Du Monde

43e Festival International du Film de La Rochelle du 26 juin au 5 juillet 2015 LE PUZZLE DES CINÉMAS DU MONDE Une fois de plus nous revient l’impossible tâche de synthétiser une édition multiforme, tant par le nombre de films présentés que par les contextes dans lesquels ils ont été conçus. Nous ne pouvons nous résoudre à en sélectionner beaucoup moins, ce n’est pas faute d’essayer, et de toutes manières, un contexte économique plutôt inquiétant nous y contraint ; mais qu’une ou plusieurs pièces essentielles viennent à manquer au puzzle mental dont nous tentons, à l’année, de joindre les pièces irrégulières, et le Festival nous paraîtrait bancal. Finalement, ce qui rassemble tous ces films, qu’ils soient encore matériels ou virtuels (50/50), c’est nous, sélectionneuses au long cours. Nous souhaitons proposer aux spectateurs un panorama généreux de la chose filmique, cohérent, harmonieux, digne, sincère, quoique, la sincérité… Ambitieux aussi car nous aimons plus que tout les cinéastes qui prennent des risques et notre devise secrète pourrait bien être : mieux vaut un bon film raté qu’un mauvais film réussi. Et enfin, il nous plaît que les films se parlent, se rencontrent, s’éclairent les uns les autres et entrent en résonance dans l’esprit du festivalier. En 2015, nous avons procédé à un rééquilibrage géographique vers l’Asie, absente depuis plusieurs éditions de la programmation. Tout d’abord, avec le grand Hou Hsiao-hsien qui en est un digne représentant puisqu’il a tourné non seulement à Taïwan, son île natale mais aussi au Japon, à Hongkong et en Chine. -

W Talking Pictures

Wednesday 3 June at 20.30 (Part I) Wednesday 17 June at 20.30 Thursday 4 June at 20.30 (Part II) Francis Ford Coppola Ingmar Bergman Apocalypse Now (US) 1979 Fanny And Alexander (Sweden) 1982 “One of the great films of all time. It shames modern Hollywood’s “This exuberant, richly textured film, timidity. To watch it is to feel yourself lifted up to the heights where packed with life and incident, is the cinema can take you, but so rarely does.” (Roger Ebert, Chicago punctuated by a series of ritual family Sun-Times) “To look at APOCALYPSE NOW is to realize that most of us are gatherings for parties, funerals, weddings, fast forgetting what a movie looks like - a real movie, the last movie, and christenings. Ghosts are as corporeal an American masterpiece.” (Manohla Darghis, LA Weekly) “Remains a as living people. Seasons come and go; majestic explosion of pure cinema. It’s a hallucinatory poem of fear, tumultuous, traumatic events occur - projecting, in its scale and spirit, a messianic vision of human warfare Talking yet, as in a dream of childhood (the film’s stretched to the flashpoint of technological and moral breakdown.” perspective is that of Alexander), time is (Owen Gleiberman, Entertainment Weekly) “In spite of its limited oddly still.” (Philip French, The Observer) perspective on Vietnam, its churning, term-paperish exploration of “Emerges as a sumptuously produced Conrad and the near incoherence of its ending, it is a great movie. It Pictures period piece that is also a rich tapestry of grows richer and stranger with each viewing, and the restoration [in childhood memoirs and moods, fear and Redux] of scenes left in the cutting room two decades ago has only April - July 2009 fancy, employing all the manners and added to its sublimity.” (Dana Stevens, The New York Times) Audience means of the best of cinematic theatrical can choose the original version or the longer 2001 Redux version. -

Intermedialtranslation As Circulation

Journal of World Literature 5 (2020) 568–586 brill.com/jwl Intermedial Translation as Circulation Chu Tien-wen, Taiwan New Cinema, and Taiwan Literature Jessica Siu-yin Yeung soas University of London, London, UK [email protected] Abstract We generally believe that literature first circulates nationally and then scales up through translation and reception at an international level. In contrast, I argue that Taiwan literature first attained international acclaim through intermedial translation during the New Cinema period (1982–90) and was only then subsequently recognized nationally. These intermedial translations included not only adaptations of literature for film, but also collaborations between authors who acted as screenwriters and film- makers. The films resulting from these collaborations repositioned Taiwan as a mul- tilingual, multicultural and democratic nation. These shifts in media facilitated the circulation of these new narratives. Filmmakers could circumvent censorship at home and reach international audiences at Western film festivals. The international success ensured the wide circulation of these narratives in Taiwan. Keywords Taiwan – screenplay – film – allegory – cultural policy 1 Introduction We normally think of literature as circulating beyond the context in which it is written when it obtains national renown, which subsequently leads to interna- tional recognition through translation. In this article, I argue that the contem- porary Taiwanese writer, Chu Tien-wen (b. 1956)’s short stories and screenplays first attained international acclaim through the mode of intermedial transla- tion during the New Cinema period (1982–90) before they gained recognition © jessica siu-yin yeung, 2020 | doi:10.1163/24056480-00504005 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the cc by 4.0Downloaded license. -

ALSO LIKE LIFE: the FILMS of HOU HSIAO-HSIEN New Addition: Hou Hsiao-Hsien in Conversation at BFI Southbank – Monday 14 September

ALSO LIKE LIFE: THE FILMS OF HOU HSIAO-HSIEN New addition: Hou Hsiao-Hsien In Conversation at BFI Southbank – Monday 14 September Thursday 13 August 2015, London The BFI is delighted to announce that one of the leading figures of the Taiwanese New Wave Hou Hsiao-Hsien, whose latest film The Assassin won Best Director at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, will make a very rare visit to the UK to take part in an In Conversation event at BFI Southbank. The event, which takes place on Monday 14 September, is part of Also Life Life: The Films of Hou Hsiao- Hsien, a major retrospective celebrating Hou’s work, which takes place from 2 Sept – 6 Oct 2015 at BFI Southbank. Hou-Hsiao-Hsien has helped put Taiwanese cinema on the international map with work that explores the island’s rapidly changing present as well as its turbulent, often bloody past, and is one of the best examples in world cinema of a director who found his own distinctive style and voice while working on the job. The season will kick off with Cute Girl (1980), Cheerful Wind (1981) and The Green Green Grass of Home (1982), all starring Hong Kong pop star Kenny Bee; these early films offer a mixture of comedy and romance and begin to show Hou’s interest in Taiwan’s regional differences, a key theme of his later films. Hou’s other early films such as The Sandwich Man (1983) and The Boys from Fengkuei (1983) dramatised engaging life stories – including his own in The Time to Live and the Time to Die (1985). -

Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND Index 2016_4.indd 1 14/12/2016 17:41 SUBJECT INDEX SUBJECT INDEX After the Storm (2016) 7:25 (magazine) 9:102 7:43; 10:47; 11:41 Orlando 6:112 effect on technological Film review titles are also Agace, Mel 1:15 American Film Institute (AFI) 3:53 Apologies 2:54 Ran 4:7; 6:94-5; 9:111 changes 8:38-43 included and are indicated by age and cinema American Friend, The 8:12 Appropriate Behaviour 1:55 Jacques Rivette 3:38, 39; 4:5, failure to cater for and represent (r) after the reference; growth in older viewers and American Gangster 11:31, 32 Aquarius (2016) 6:7; 7:18, Céline and Julie Go Boating diversity of in 2015 1:55 (b) after reference indicates their preferences 1:16 American Gigolo 4:104 20, 23; 10:13 1:103; 4:8, 56, 57; 5:52, missing older viewers, growth of and A a book review Agostini, Philippe 11:49 American Graffiti 7:53; 11:39 Arabian Nights triptych (2015) films of 1970s 3:94-5, Paris their preferences 1:16 Aguilar, Claire 2:16; 7:7 American Honey 6:7; 7:5, 18; 1:46, 49, 53, 54, 57; 3:5: nous appartient 4:56-7 viewing films in isolation, A Aguirre, Wrath of God 3:9 10:13, 23; 11:66(r) 5:70(r), 71(r); 6:58(r) Eric Rohmer 3:38, 39, 40, pleasure of 4:12; 6:111 Aaaaaaaah! 1:49, 53, 111 Agutter, Jenny 3:7 background -

Journal of Asian Studies Contemporary Chinese Cinema Special Edition

the iafor journal of asian studies Contemporary Chinese Cinema Special Edition Volume 2 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Editor: Seiko Yasumoto ISSN: 2187-6037 The IAFOR Journal of Asian Studies Volume 2 – Issue – I IAFOR Publications Executive Editor: Joseph Haldane The International Academic Forum The IAFOR Journal of Asian Studies Editor: Seiko Yasumoto, University of Sydney, Australia Associate Editor: Jason Bainbridge, Swinburne University, Australia Published by The International Academic Forum (IAFOR), Japan Executive Editor: Joseph Haldane Editorial Assistance: Rachel Dyer IAFOR Publications. Sakae 1-16-26-201, Naka-ward, Aichi, Japan 460-0008 Journal of Asian Studies Volume 2 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 IAFOR Publications © Copyright 2016 ISSN: 2187-6037 Online: joas.iafor.org Cover image: Flickr Creative Commons/Guy Gorek The IAFOR Journal of Asian Studies Volume 2 – Issue I – Spring 2016 Edited by Seiko Yasumoto Table of Contents Notes on contributors 1 Welcome and Introduction 4 From Recording to Ritual: Weimar Villa and 24 City 10 Dr. Jinhee Choi Contested identities: exploring the cultural, historical and 25 political complexities of the ‘three Chinas’ Dr. Qiao Li & Prof. Ros Jennings Sounds, Swords and Forests: An Exploration into the Representations 41 of Music and Martial Arts in Contemporary Kung Fu Films Brent Keogh Sentimentalism in Under the Hawthorn Tree 53 Jing Meng Changes Manifest: Time, Memory, and a Changing Hong Kong 65 Emma Tipson The Taste of Ice Kacang: Xiaoqingxin Film as the Possible 74 Prospect of Taiwan Popular Cinema Panpan Yang Subtitling Chinese Humour: the English Version of A Woman, a 85 Gun and a Noodle Shop (2009) Yilei Yuan The IAFOR Journal of Asian Studies Volume 2 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Notes on Contributers Dr. -

Film Language Interpretation of the Image of the City Based on the Documentary Method

Fachbereich Erziehungswissenschaft und Psychologie der Freien Universität Berlin Film Language Interpretation of the Image of the City Based on the Documentary Method Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktorin der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) vorgelegt von (M.Sc., Peking University) Hao, Xiaofei Berlin, 2014 Erstgutachter Univ.-Prof. Dr. Ralf Bohnsack Zweitgutachter Univ.-Prof. Dr. Christoph Wulf Datum der Disputation: 04.11.2014 Contents Erklärung ............................................................................................................................................... I Preface ................................................................................................................................................... II Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................ III Chapter 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 2 Theory, literature and methodology ................................................................. 9 1. The image of the city .......................................................................................................................... 9 1.1 Lynch’s image system ................................................................................................................. 10 1.2 Discussion and applications of Lynch’s findings in film studies ............................................... -

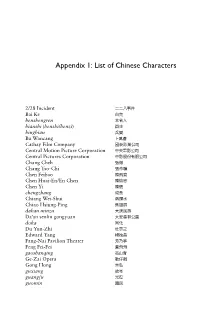

Appendix 1: List of Chinese Characters

Appendix 1: List of Chinese Characters 2/28 Incident 二二八事件 Bai Ke 白克 benshengren 本省人 bianshi (benshi/benzi) 辯士 bingbian 兵變 Bu Wancang 卜萬蒼 Cathay Film Company 國泰影業公司 Central Motion Picture Corporation 中央電影公司 Central Pictures Corporation 中影股份有限公司 Chang Cheh 張徹 Chang Tso-Chi 張作驥 Chen Feibao 陳飛寶 Chen Huai-En/En Chen 陳懷恩 Chen Yi 陳儀 chengzhang 成長 Chiang Wei- Shui 蔣謂水 Chiao Hsiung- Ping 焦雄屏 dahan minzu 大漢民族 Da’an senlin gongyuan 大安森林公園 doka 同化 Du Yun- Zhi 杜雲之 Edward Yang 楊德昌 Fang- Nai Pavilion Theater 芳乃亭 Feng Fei- Fei 鳳飛飛 gaoshanqing 高山青 Ge- Zai Opera 歌仔戲 Gong Hong 龔弘 guxiang 故鄉 guangfu 光復 guomin 國民 188 Appendix 1 guopian 國片 He Fei- Guang 何非光 Hou Hsiao- Hsien 侯孝賢 Hu Die 胡蝶 Huang Shi- De 黃時得 Ichikawa Sai 市川彩 jiankang xieshi zhuyi 健康寫實主義 Jinmen 金門 jinru shandi qingyong guoyu 進入山地請用國語 juancun 眷村 keban yingxiang 刻板印象 Kenny Bee 鍾鎮濤 Ke Yi-Zheng 柯一正 kominka 皇民化 Koxinga 國姓爺 Lee Chia 李嘉 Lee Daw- Ming 李道明 Lee Hsing 李行 Li You-Xin 李幼新 Li Xianlan 李香蘭 Liang Zhe- Fu 梁哲夫 Liao Huang 廖煌 Lin Hsien- Tang 林獻堂 Liu Ming- Chuan 劉銘傳 Liu Na’ou 劉吶鷗 Liu Sen- Yao 劉森堯 Liu Xi- Yang 劉喜陽 Lu Su- Shang 呂訴上 Ma- zu 馬祖 Mao Xin- Shao/Mao Wang- Ye 毛信孝/毛王爺 Matuura Shozo 松浦章三 Mei- Tai Troupe 美臺團 Misawa Mamie 三澤真美惠 Niu Chen- Ze 鈕承澤 nuhua 奴化 nuli 奴隸 Oshima Inoshi 大島豬市 piaoyou qunzu 漂游族群 Qiong Yao 瓊瑤 qiuzhi yu 求知慾 quanguo gejie 全國各界 Appendix 1 189 renmin jiyi 人民記憶 Ruan Lingyu 阮玲玉 sanhai 三害 shandi 山地 Shao 邵族 Shigehiko Hasumi 蓮實重彦 Shihmen Reservoir 石門水庫 shumin 庶民 Sino- Japanese Amity 日華親善 Society for Chinese Cinema Studies 中國電影史料研究會 Sun Moon Lake 日月潭 Taiwan Agricultural Education Studios