Protecting Sydney's Water Catchments from Coal And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sydney Water in 1788 Was the Little Stream That Wound Its Way from Near a Day Tour of the Water Supply Hyde Park Through the Centre of the Town Into Sydney Cove

In the beginning Sydney’s first water supply from the time of its settlement Sydney Water in 1788 was the little stream that wound its way from near A day tour of the water supply Hyde Park through the centre of the town into Sydney Cove. It became known as the Tank Stream. By 1811 it dams south of Sydney was hardly fit for drinking. Water was then drawn from wells or carted from a creek running into Rushcutter’s Bay. The Tank Stream was still the main water supply until 1826. In this whole-day tour by car you will see the major dams, canals and pipelines that provide water to Sydney. Some of these works still in use were built around 1880. The round trip tour from Sydney is around 350 km., all on good roads and motorway. The tour is through attractive countryside south Engines at Botany Pumping Station (demolished) of Sydney, and there are good picnic areas and playgrounds at the dam sites. source of supply. In 1854 work started on the Botany Swamps Scheme, which began to deliver water in 1858. The Scheme included a series of dams feeding a pumping station near the present Sydney Airport. A few fragments of the pumping station building remain and can be seen Tank stream in 1840, from a water-colour by beside General Holmes Drive. Water was pumped to two J. Skinner Prout reservoirs, at Crown Street (still in use) and Paddington (not in use though its remains still exist). The ponds known as Lachlan Swamp (now Centennial Park) only 3 km. -

History of Sydney Water

The history of Sydney Water Since the earliest days of European settlement, providing adequate water and sewerage services for Sydney’s population has been a constant challenge. Sydney Water and its predecessor, the Metropolitan Water Sewerage and Drainage Board, has had a rich and colourful history. This history reflects the development and growth of Sydney itself. Over the past 200 years, Sydney’s unreliable rainfall has led to the development of one of the largest per capita water supplies in the world. A truly reliable water supply was not achieved until the early 1960s after constructing Warragamba Dam. By the end of the 20th Century, despite more efficient water use, Sydney once again faced the prospect of a water shortage due to population growth and unreliable rainfall patterns. In response to this, the NSW Government, including Sydney Water, started an ambitious program to secure Sydney’s water supplies. A mix of options has been being used including water from our dams, desalination, wastewater recycling and water efficiency. Timeline 1700s 1788 – 1826 Sydney was chosen as the location for the first European settlement in Australia, in part due to its outstanding harbour and the availability of fresh water from the Tank Stream. The Tank Stream remained Sydney’s main water source for 40 years. However, pollution rapidly became a problem. A painting by J. Skinner Prout of the Tank Stream in the 1840s 1800s 1880 Legislation was passed under Sir Henry Parkes, as Premier, which constitutes the Board of Water Supply and Sewerage. 1826 The Tank Stream was abandoned as a water supply because of pollution from rubbish, sewage and runoff from local businesses like piggeries. -

Heritage Inventory Sheet

Heritage Inventory Sheet Item Name Parramatta Road Milestone Recommended Name Parramatta Road Milestones Group Site Image Address Parramatta Road, between Dartbrook Road and Station Street, Auburn NSW 2144; and Parramatta Road, between Platform Street and Delhi Street, Lidcombe NSW 2144. Lot/Section/DP - - - Draft Cumberland LEP ID I295 Former LEP ID A51 (Auburn LEP) Parramatta Road Milestone; and A52 (Auburn LEP) Parramatta Road Milestone. Heritage Conservation Not included Area Date Updated March 2020 Significance Level LOCAL Site Type Level 1 Built Level 2 Exploration, Survey and Events Heritage Study 2019 – Extent Heritage Pty Ltd Curtilage Map Note: Former item number used to identify individual milestones. Revised curtilage recommended – refer below Heritage Study 2019 – Extent Heritage Pty Ltd Statement of Significance The Parramatta Road Milestones Group are of local significance for their historic, associative, aesthetic and representative heritage values. The milestones are historically significant in their role of marking the distance of the journey along Parramatta Road from Parramatta to Sydney. They are a tangible reminder of the continuing importance of Parramatta Road as a main highway between Sydney, Parramatta and the West. While some milestones are no longer located in their exact original location, they relate to their original location and mark the significance of Parramatta Road and the construction of roads by the Department of Main Roads. The milestones are associated with the Department of Main Roads in 1934 and their implementation of the "Type D" milestones for use in urban situations. The milestones have aesthetic significance through their notable lettering and form, and their role as a landscape element. -

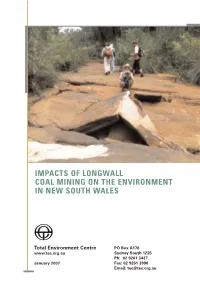

Impacts of Longwall Coal Mining on the Environment in New South Wales

IMPACTS OF LONGWALL COAL MINING ON THE ENVIRONMENT IN NEW SOUTH WALES Total Environment Centre PO Box A176 www.tec.org.au Sydney South 1235 Ph: 02 9261 3437 January 2007 Fax: 02 9261 3990 Email: [email protected] CONTENTS 01 OVERVIEW 3 02 BACKGROUND 5 2.1 Definition 5 2.2 The Longwall Mining Industry in New South Wales 6 2.3 Longwall Mines & Production in New South Wales 2.4 Policy Framework for Longwall Mining 6 2.5 Longwall Mining as a Key Threatening Process 7 03 DAMAGE OCCURRING AS A RESULT OF LONGWALL MINING 9 3.1 Damage to the Environment 9 3.2 Southern Coalfield Impacts 11 3.3 Western Coalfield Impacts 13 3.4 Hunter Coalfield Impacts 15 3.5 Newcastle Coalfield Impacts 15 04 LONGWALL MINING IN WATER CATCHMENTS 17 05 OTHER EMERGING THREATS 19 5.1 Longwall Mining near National Parks 19 5.2 Longwall Mining under the Liverpool Plains 19 5.3 Longwall Top Coal Caving 20 06 REMEDIATION & MONITORING 21 6.1 Avoidance 21 6.2 Amelioration 22 6.3 Rehabilitation 22 6.4 Monitoring 23 07 KEY ISSUES AND RECOMMENDATIONS 24 7.1 The Approvals Process 24 7.2 Buffer Zones 26 7.3 Southern Coalfields Inquiry 27 08 APPENDIX – EDO ADVICE 27 EDO Drafting Instructions for Legislation on Longwall Mining 09 REFERENCES 35 We are grateful for the support of John Holt in the production of this report and for the graphic design by Steven Granger. Cover Image: The now dry riverbed of Waratah Rivulet, cracked, uplifted and drained by longwall mining in 2006. -

Dam Safety Committee H Middleton, Mining Regulation Officer, NSW Dam Safety Committee

NSW Dams Safety Committee (DSC) Submission to the Independent Expert Panel for Mining in the Catchment – Task 2 The Committee understands Task #2 to be: Undertake a review of current coal mining in the Greater Sydney Water Catchment Special Areas with a particular focus on risks to the quantity of water available, the environmental consequences for swamps and the issue of cumulative impacts. 1. BACKGROUND The Dams Safety Committee (DSC) is a NSW government body that was created under the Dams Safety Act 1978. The DSC’s current role under the existing 1978 Act in regards to mining is to ensure the safety of any prescribed dam and to ensure there is no significant loss of stored waters which would threaten lives (other than underground miners) or whereby the risks to the community from uncontrolled loss of storage are tolerably low. In regards to the matter of what is deemed a significant loss of water that could threaten the health of the population. The DSC in 2008/09 in consultation with the SCA (now WaterNSW) developed a Tolerable Storage Loss criterion (see more on this later) in relation to mining at Dendrobium near Cordeaux Reservoir. The DSC has subsequently, due to lack of other advice adopted the same criteria for other mines in the Catchment. DSC delineates Notification Areas around certain prescribed dams and their storages under Section 369 of the Mining Act. These Notification Areas are small areas designed for administrative purposes and within which it is considered possible that the effects of mining may potentially directly impact either dams and/or their water storages. -

Water Storages in NSW

PO Box R1437 NSWIC Royal Exchange NSW 1225 NEW SOUTH WALES Tel: 02 9251 8466 Fax: 02 9251 8477 IRRIGATORS’ [email protected] COUNCIL www.nswic.org.au ABN: 49 087 281 746 Submission to the Standing Committee on State Development Adequacy of Water Storages in NSW 120831 Mark Moore Policy Analyst Member Organisations: Bega Cheese Limited, Border Rivers Food & Fibre, Coleambally Irrigation Co-Op Ltd, Cotton Australia, Gwydir Valley Irrigators’ Association Inc., High Security Irrigators Inc, Hunter Valley Water Users’ Association, Lachlan Valley Water, Macquarie River Food & Fibre, Mid Coast Dairy Advancement Group, Mungindi-Menindee Advisory Council, Murray Irrigation Limited, Murray Valley Water Diverters’ Association, Murrumbidgee Groundwater Inc., Murrumbidgee Irrigation Ltd, Murrumbidgee Private Irrigators’ Inc., Murrumbidgee Valley Food and Fibre Association, Namoi Water, NSW Farmers’ Association, Ricegrowers’ Association of Australia, Richmond Wilson Combined Water Users Association, Riverina Citrus, Southern Riverina Irrigators, South Western Water Users’, West Corurgan Private Irrigation District, Western Murray Irrigation, Wine Grapes Marketing Board. Introduction NSW Irrigators’ Council (NSWIC) represents more than 12,000 irrigation farmers across NSW. These irrigators access regulated, unregulated and groundwater systems. Our members include valley water user associations, food and fibre groups, irrigation corporations and commodity groups from the rice, cotton, dairy and horticultural industries. This document represents the views of the members of NSWIC. However each member reserves the right to independent policy on issues that directly relate to their areas of operation, or expertise, or any other issues that they may deem relevant. 1 | P a g e Background NSWIC, being the peak body for irrigators in NSW, appreciates the opportunity to make a submission to this Inquiry. -

Temporal and Spatial Study of Thunderstorm Rainfall in the Greater Sydney Region Ali Akbar Rasuly University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1996 Temporal and spatial study of thunderstorm rainfall in the Greater Sydney region Ali Akbar Rasuly University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Rasuly, Ali Akbar, Temporal and spatial study of thunderstorm rainfall in the Greater Sydney region, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Geosciences, University of Wollongong, 1996. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/1986 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] TEMPORAL AND SPATIAL STUDY OF THUNDERSTORM RAINFALL IN THE GREATER SYDNEY REGION A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree UNIVERSITY O* DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by ALIAKBAR RASULY B.Sc. & M.Sc. (IRAN, TABRIZ University) SCHOOL OF GEOSCIENCES 1996 CERTIFICATION The work presented herein has not been submitted to any other university or institution for a higher degree and, unless acknowledged, is my own original work. A. A. Rasuly February 1996 i ABSTRACT Thunderstorm rainfall is considered as a very vital climatic factor because of its significant effects and often disastrous consequences upon people and the natural environment in the Greater Sydney Region. Thus, this study investigates the following aspects of thunderstorm rainfall climatology of the region between 1960 to 1993. In detail, it was found that thunderstorm rainfalls in Sydney have marked diurnal and seasonal variations. They are most frequent in the spring and summer and during the late afternoon and early evening. Thunderstorms occur primarily over the coastal areas and mountains, and less frequently over the lowland interior of the Sydney basin. -

2. Environmental Context 23 Landforms at Plateau Level Vary Between Being Either Narrow Or Broad

2 Environmental Context This chapter outlines the physical context of the Upper Nepean. The location and boundaries are delineated, and the topography, geology and vegetation are defined. The broader geographic and environmental context, in which the study area is situated, is also described. The four catchments are discussed individually. They each have different overall characteristics, which would have presented a different suite of opportunities and constraints to human occupation. It is assumed that the area is likely to have been used by Aboriginal people since the late Pleistocene through to the historic era. Accordingly, consideration is given to climatic variation and corresponding changes to the physical environment over that time. The weathering and site formation processes, which created and continue to form rock shelters, are described. These processes have considerable relevance to the nature of human occupation of shelters and to their potential to preserve the rock art they host. 2.1 Introduction The study area is located on the Woronora Plateau, situated between the Illawarra Escarpment and the watershed divide between the Nepean and Bargo rivers. The plateau is deeply dissected, and is drained by six major rivers: the Georges, Woronora, Cataract, Cordeaux, Avon and Nepean (Figure 2.1). The study area is defined on a catchment (the Upper Nepean) and land use basis (it is confined to the Metropolitan Special Area), and it occupies the southern extent of the Woronora Plateau. The Metropolitan Special Area measures c. 78,000 hectares and is managed jointly by the SCA and the NSW OEH. Public access has been restricted for a considerable time, and it is now a significant naturally vegetated and largely undeveloped area (Mills et al. -

C H a I N M a I L [email protected] No

c h a i n m a i l http://www.bikenorth.org.au/ [email protected] No. 35 August 2004 Contents M2 Cyclist Issues UPDATE! M2 Cyclist Issues UPDATE! 1 Doug Stewart Events 2 In the last Chain Mail we reported that the M2 operators has raised some safety concerns and Diary Dates 2 that Bike North was preparing a submission. Further information gathered since then suggests Bike North AGM & Picnic 2 Bike North may need to put together a strong argument to keep the M2 as a direct and quick commuter and training route for local cyclists. Touring / Riding 3 The Ryde Council Bicycle Advisory Committee recently met with reps from the Hills motorway A Tale of Two Canals (and One Reservoir)Chain 3 and consultants Mail GHD, whose plans to make changes to the M2 seem well advanced. Spoke-n 4 WHY ARE CHANGES BEING PLANNED? A Blitz Of Young Blades 4 The pressure for change is from new roads developing to the east (Lane Cove Tunnel) and the Chatswood to surf and west (M7 and M2 to F3 link) which create the opportunity for more vehicles on the M2, and not quite back again. 4 therefore more revenue for the company. Cycling for transport 5 The current chokepoint in the morning peak is the toll plaza. The M2 is working to install Murphy, the law, and our lore 5 improved technology allowing for faster E-Tag recognition and distance based tolls may be considered as well. The legal side 6 With toll Bike Bits 6 collection solved Crank Rites 6 the next issue is BN Member Product Review 7 vehicle capacity. -

System Blueprints Aligning Short-Term Investment with Long-Term Strategy

Modelling & Planning ISSN 2206-1991 Volume 2 No 4 2017 https://doi.org/10.21139/wej.2017.034 SYSTEM BLUEPRINTS ALIGNING SHORT-TERM INVESTMENT WITH LONG-TERM STRATEGY A Jaiswal, C Moore, M Wilton, M Healey ABSTRACT Big data and smart predictive tools are enabling Maximising the performance and utilisation of existing utilities to gain a clearer picture of asset information assets to enable future adaptability and flexibility within and performance, thus enabling a more balanced an envelope of prudent and efficient expenditure is view of risk. Sydney Water has capitalised on this by complex and challenging, particularly in the context of developing an adaptive strategic planning framework maintaining service level obligations. In the emerging that efficiently integrates portfolios and product digital age, “big data” is enabling utilities to better drivers in the development of System Blueprints leverage and manage these challenges. Sydney Water (Figure 1). The System Blueprints integrate planning has capitalised on this by developing an adaptive across portfolios and products in delivering improved strategic planning framework that efficiently integrates service to customers, whilst at the same time reducing portfolios and product drivers in the development of investment requirements. System Blueprints. The System Blueprints map short- This paper presents the foundation of term and long-term system priorities (integrating the adaptive strategic planning treatment facilities and networks) in the context of framework process, which is multiple drivers. They provide a clearer picture of the considered to be more: long-term context and system requirements, which ◗ intelligent – tapping in turn promotes optimised investment decisions and into systems, improved customer services. -

Inquiry Into Proposal to Raise the Warragamba Dam Wall

Submission No 284 INQUIRY INTO PROPOSAL TO RAISE THE WARRAGAMBA DAM WALL Name: Dr Anthony Green Date Received: 8 September 2019 Submission to the Legislative Council Select Committee on the Proposal to Raise the Warragamba Dam Wall Dr A.R. Green, B.SC. , PhD. Director: ARGSAB Pacific Pty Ltd Visiting Principle Fellow, School of Computer Science and Software Engineering, University of Wollongong 9 September 2019 1 Summary of Recommendations 1. It is my submission that the raising of the dam wall does not build resilience for Sydney, NSW or Australia, but increases the vulnerability of the population to unnecessary and avoidable risks. 2. My submission is that the committee should recommend that the draft EIS and Draft Business cases together with the original papers requesting this proposal, cost calculations, risk and vulnerability assessments be published together with assessments of who will pay for externality risks. 3. The committee should also recommend the final EIS and final Business case be published with all the supporting cost benefit papers including how externality costs are to handled. 4. The committee should investigate why dam collapse was not included in the Hawkesbury-Nepean flood study. 5. It is a recommendation that the SES develops and test plans for a dam failure of all the major dams in NSW if they have not already done so and publish the results. 6. It is my submission that other options are available that do increase resilience for Sydney and NSW, and should be enacted. This includes developing desalination technology which has come a long way since the first desalination plant was built in Sydney, the provision of at least 10 desalination plants as well as lowering the dam water level by some 30m. -

Silver Perch)

Consultation Document on Listing Eligibility and Conservation Actions Bidyanus bidyanus (Silver Perch) You are invited to provide your views and supporting reasons related to: 1) the eligibility of Bidyanus bidyanus (Silver Perch) for inclusion on the EPBC Act threatened species list in the Endangered category; and 2) the necessary conservation actions for the above species. Evidence provided by experts, stakeholders and the general public are welcome. Responses can be provided by any interested person. Anyone may nominate a native species, ecological community or threatening process for listing under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) or for a transfer of an item already on the list to a new listing category. The Threatened Species Scientific Committee (the Committee) undertakes the assessment of species to determine eligibility for inclusion in the list of threatened species and provides its recommendation to the Australian Government Minister for the Environment and Energy. Responses are to be provided in writing either by email to: [email protected] or by mail to: The Director Marine and Freshwater Species Conservation Section Biodiversity Conservation Division Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment PO Box 858 Canberra ACT 2601 Responses are required to be submitted by 12 March 2021. Contents of this information package Page General background information about listing threatened species 2 Information about this consultation process 3 Draft information about the common name and its eligibility for listing 4 Conservation actions for the species 24 References cited 26 Collective list of questions – your views 34 Bidyanus bidyanus (Silver Perch) consultation document Page 1 of 36 General background information about listing threatened species The Australian Government helps protect species at risk of extinction by listing them as threatened under Part 13 of the EPBC Act.