Title Tin Mining in Cornwall During the Inter-War Years 1918-38

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daily Report Thursday, 20 July 2017 CONTENTS

Daily Report Thursday, 20 July 2017 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 20 July 2017 and the information is correct at the time of publication (06:34 P.M., 20 July 2017). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 10 Social Tariffs: Torfaen 19 ATTORNEY GENERAL 10 Taxation: Electronic Hate Crime: Prosecutions 10 Government 19 BUSINESS, ENERGY AND Technology and Innovation INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 10 Centres 20 Business: Broadband 10 UK Consumer Product Recall Review 20 Construction: Employment 11 Voluntary Work: Leave 21 Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy: CABINET OFFICE 21 Mass Media 11 Brexit 21 Department for Business, Elections: Subversion 21 Energy and Industrial Strategy: Electoral Register 22 Staff 11 Government Departments: Directors: Equality 12 Procurement 22 Domestic Appliances: Safety 13 Intimidation of Parliamentary Economic Growth: Candidates Review 22 Environment Protection 13 Living Wage: Jarrow 23 Electrical Safety: Testing 14 New Businesses: Newham 23 Fracking 14 Personal Income 23 Insolvency 14 Public Sector: Blaenau Gwent 24 Iron and Steel: Procurement 17 Public Sector: Cardiff Central 24 Mergers and Monopolies: Data Public Sector: Ogmore 24 Protection 17 Public Sector: Swansea East 24 Nuclear Power: Treaties 18 Public Sector: Torfaen 25 Offshore Industry: North Sea 18 Public Sector: Wrexham 25 Performing Arts 18 Young People: Cardiff Central -

Minewater Study

National Rivers Authority (South Western-Region).__ Croftef Minewater Study Final Report CONSULTING ' ENGINEERS;. NATIONAL RIVERS AUTHORITY SOUTH WESTERN REGION SOUTH CROFTY MINEWATER STUDY FINAL REPORT KNIGHT PIESOLD & PARTNERS Kanthack House Station Road September 1994 Ashford Kent 10995\r8065\MC\P JS TN23 1PP ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 125218 r:\10995\f8065\fp.Wp5 National Rivers Authority South Crofty Minewater Study South Western Region Final Report CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY -1- 1. INTRODUCTION 1-1 2. THE SOUTH CROFTY MINE 2-1 2.1 Location____________________________________________________ 2-1 ________2.2 _ Mfning J4istojy_______________________________________ ________2-1. 2.3 Geology 2-1 2.4 Mine Operation 2-2 3. HYDROLOGY 3-1 3.1 Groundwater 3-1 3.2 Surface Water 3-1 3.3 Adit Drainage 3-2 3.3.1 Dolcoath Deep and Penhale Adits 3-3 3.3.2 Shallow/Pool Adit 3-4 3.3.3 Barncoose Adit 3-5 4. MINE DEWATERING 4-1 4.1 Mine Inflows 4-1 4.2 Pumped Outflows 4-2 4.3 Relationship of Rainfall to Pumped Discharge 4-3 4.4 Regional Impact of Dewatering 4-4 4.5 Dewatered Yield 4-5 4.5.1 Void Estimates from Mine Plans 4-5 4.5.2 Void Estimate from Production Tonnages 4-6 5. MINEWATER QUALITY 5-1 5.1 Connate Water 5-2 5.2 South Crofty Discharge 5-3 5.3 Adit Water 5-4 5.4 Acidic Minewater 5-5 Knif»ht Piesold :\10995\r8065\contants.Wp5 (l) consulting enCneers National Rivers Authority South Crofty Minewater Study South Western Region Final Report CONTENTS (continued) Page 6. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Local

Title: CIoS Local Enterprise Partnership Board Date: Wednesday 28 July 2021 Time: 10.00 to 13.00 Venue: : - Council Offices, Chy Trevail, Bodmin, PL31 2FR Livestream Link: https://teams.microsoft.com/l/meetup- join/19%3ameeting_NmFkNzY4NWMtNmVjMy00YTgxLWFhZTMtMDZlZDRlZGIyNTU5 %40thread.v2/0?context=%7b%22Tid%22%3a%22efaa16aa-d1de-4d58-ba2e- 2833fdfdd29f%22%2c%22Oid%22%3a%22fa9d3751-6eb5-4308-b8c3- 006db67ed9ac%22%2c%22IsBroadcastMeeting%22%3atrue%7d&btype=a&role=a Agenda Item Lead Action 1. 10.00 Welcome and Introductions Apologies for Absence Directors: Louis Mathers Officers: Phil Mason, John Curnow 2. 10.05 Declarations of Interest ALL 3. 10.10 LEP Board (31 March 2021) 3 .1 Minutes (Pages 3 - 11) MD To note 3 .2 Action Summary (Page 12) GCG To note 4. Strategic Matters 4 .1 10.20 Chair Update MD To note 4 .2 10.30 CEO Report, with a focus on: (Pages 13 - 65) GCG To note/ Labour market and skills challenges presentation Green Industrial Revolution 4 .3 11.25 Fishing Sector Update (Pages 66 - 68) MD/NC Decision Page 1 4 .4 11.50 Nominations Committee Update (Pages 69 - GCG Decision 122) 4 .5 12.15 Audit & Assurance Committee Update (Pages GCG Decision 123 - 198) 4 .6 12.25 Enterprise Zones Board Update (Pages 199 - SJ/GCG To note 202) 4 .7 12.35 Any other business 5. Exclusion of Press and Public 5 .1 12.40 Investment & Oversight Panel Update (Pages MD/GCG To note 203 - 206) 5 .2 12.50 Any other confidential business ALL Page 2 Agenda No. 3.1 Information Classification: CONTROLLED CORNWALL AND ISLES OF SCILLY LOCAL ENTERPRISE PARTNERSHIP MINUTES of a Meeting of the Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Local Enterprise Partnership held in the Online - Virtual Meeting on Wednesday 31 March 2021 commencing at 10.00 am. -

The Cornish Mining World Heritage Events Programme

Celebrating ten years of global recognition for Cornwall & west Devon’s mining heritage Events programme Eighty performances in over fifty venues across the ten World Heritage Site areas www.cornishmining.org.uk n July 2006, the Cornwall and west Devon Mining Landscape was added to the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites. To celebrate the 10th Ianniversary of this remarkable achievement in 2016, the Cornish Mining World Heritage Site Partnership has commissioned an exciting summer-long set of inspirational events and experiences for a Tinth Anniversary programme. Every one of the ten areas of the UK’s largest World Heritage Site will host a wide variety of events that focus on Cornwall and west Devon’s world changing industrial innovations. Something for everyone to enjoy! Information on the major events touring the World Heritage Site areas can be found in this leaflet, but for other local events and the latest news see our website www.cornish-mining.org.uk/news/tinth- anniversary-events-update Man Engine Double-Decker World Record Pasty Levantosaur Three Cornishmen Volvo CE Something BIG will be steaming through Kernow this summer... Living proof that Cornwall is still home to world class engineering! Over 10m high, the largest mechanical puppet ever made in the UK will steam the length of the Cornish Mining Landscape over the course of two weeks with celebratory events at each point on his pilgrimage. No-one but his creators knows what he looks like - come and meet him for yourself and be a part of his ‘transformation’: THE BIG REVEAL! -

A Unique Opportunity for Copper, Tin and Lithium in Cornwall

A unique opportunity for copper, tin and lithium in Cornwall All information ©Cornish Metals Inc. All Rights Reserved. 1 Cornish Metals Inc Corporate Presentation Disclaimer This presentation may contain forward-looking statements which involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors which may cause the actual results, performance, or achievements to be materially different from any future results, performance or achievements expressed or implied by such forward-looking statements. Forward looking statements may include statements regarding exploration results and budgets, resource estimates, work programs, strategic plans, market price of metals, or other statements that are not statements of fact. Although the expectations reflected in such forward-looking statements are reasonable, there is no assurance that such expectations will prove to have been correct. Various factors that may affect future results include, but are not limited to: fluctuations in market prices of metals, foreign currency exchange fluctuations, risks relating to exploration, including resource estimation and costs and timing of commercial production, requirements for additional financing, political and regulatory risks. Accordingly, undue reliance should not be placed on forward-looking statements. All technical information contained within this presentation has been reviewed and approved for disclosure by Owen Mihalop, (MCSM, BSc (Hons), MSc, FGS, MIMMM, CEng), Cornish Metals’ Qualified Person as designated by NI 43-101. Readers are further referred -

The Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Local Enterprise Partnership (LEP) Was Launched in May 2011

Written evidence submitted by Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Local Enterprise Partnership (INS0039) The Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Local Enterprise Partnership (LEP) was launched in May 2011. Private sector-led, it is a partnership between the private and public sectors and is driving the economic strategy for the region, determining local priorities and undertaking activities to drive growth and the creation of local jobs. Executive Summary The Government’s Industrial Strategy should be refreshed to include wider economic, social and environmental factors that are now in play post Covid 19 by building on all of England’s Local Industrial Strategies. Industrial Strategy Grand Challenges should be updated and localised, within a national framework, and should consider the levelling up agenda, climate change, regional imbalances and measures to reduce inequality/social inclusion. The refresh should use the guiding principle of devolving decision making and delivery. The focus on key sectors in the current Industrial Strategy is sufficient if a narrow view on “growth” is used or if “trickle down” economic policies are adopted. However, whilst this approach will raise the productivity and growth of some areas it will not benefit all areas equally and those areas furthest from key industrial centres will see little or no benefit. As the future prosperity of the UK depends on unlocking the potential of all its areas, towns, high streets businesses and residents the revised Industrial Strategy needs to be more inclusive and allow for different areas to make different contributions to overall productivity levels and growth. The immense productivity gap that currently exists between the prosperous South East of England and the rest of the country on the other must be therefore be levelled-up by investing in the LEP areas that are currently lagging behind. -

Corporate Business Plan 2016/17 – 2019/20

Business Plan 2016 - 2020 Delivering our Strategy www.cornwall.gov.uk Contents Page Foreword 2 1. Introduction 3 1.1 Our Strategy 3 1.2 Context 4 1.3 Our Corporate Business Plan 5 2. Progress to date – Strategic Overview: 6 Incorporates updates on the ‘Ambitious Cornwall’, ‘Engaging with our communities’ and ‘Partners working together’ strategic aims 3. Delivering the Council Strategy: Greater access, Driving the 10 economy, Stewarding the assets 3.1 Strategy, Economy, Enterprise & Environment 10 3.2 Commissioning & Asset Management 15 3.3 Planning & Enterprise 19 4. Delivering the Council Strategy: Healthier and safe 22 communities 4.1 Children’s Early Help, Psychology & Social Care 22 4.2 Commissioning Performance & Improvement 25 4.3 Adult Care & Support 29 4.4 Public Health 32 4.5 Learning and Achievement 35 4.6 Fire, Rescue and Community Safety 38 4.7 Public Protection 39 5. Delivering the Council Strategy: Being efficient, effective 45 and innovative 5.1 Customers and Communities 45 5.2 Business Planning & Development / People Management, 48 Development & Wellbeing 5.3 Governance and Information 51 6. Managing the Plan 54 6.1 Business & Service Planning 54 6.2 Performance management and reporting 55 6.3 Management of risk 55 6.4 Organisational development framework 56 7. Financial Resources 58 8. Conclusion 59 9. Acronyms 60 Corporate Business Plan 2016/17 – 2019/20 JOINT FOREWORD Welcome to the Council’s Business Plan for the next four years. When we approved our Council Strategy in 2014 we knew that we would be facing some significant challenges over the course of this decade, but also that there were tremendous opportunities for both the Council and for Cornwall if we worked with colleagues in the public, private and community sectors to deliver our ambition of creating a more sustainable and prosperous Cornwall that is resilient and resourceful, a place where communities are strong and where the most vulnerable are protected. -

CORNISH and DEVONSHIRE MINES. East Bolmbush Mine Is in the Township and Parish System

• XVI CORNISH AND DEVONSHIRE MINES. East Bolmbush Mine is in the township and parish system. and comists of 9,000 sl1ares. The prospPcts of of Stoke Climsland. union of Launceston, Jmndred of t11is mine l1ave much improved lately. Tbe secretary is East, Cornwall, and within the mining distrirt of G. Kieckhoefer, of 50 Threadneedle !>treet, London. Callington; it is situated 2~ miles from the town of East Tolgus Mine is in the parish and union of Red Callington. The nearest shipping place for ores and ruth, hundred of Penwith, Cornwall, within the bound!! machinery is at Calstock quay, 4 miles from the mine, of the mauor of Treleigh and mining district of Redruth. und the nearest railw»y t!tation is at Plymouth, 14 It is situated half a mile north of the town of Red from the mine, and 260 from London. The mine i~ ruth, which is the nearest railway station, and 26i miles held under a lease for 21 years, from 1850, at a from Lortlon. The nearest shipping place for ores and royalty of 1-15th, granted by His Royal Highnes" the machinery is at Portreat h, 3~ n.iles from the mine. The Duke of Cornwall. The country is granite and killa!:', mine is held under a Jotoase for 21 years, from 1853, at a anti the dip south and north; the cleavnge of the royalty of 1-16th, granted by R. 'I'. Garden and orhers, clay slate is north and south; the nearest granite is at ofTonbridge Welh. The country is killas or slate, elvan, Kit Hill. -

Cobalt Mineralisation in Cornwall – a New Discovery at Porthtowan

G.K. Rollinson, N. Le Boutillier and R. Selly COBALT MINERALISATION IN CORNWALL – A NEW DISCOVERY AT PORTHTOWAN G.K. ROLLINSON 1, N. LE BOUTILLIER AND R. SELLY Rollinson, G.K., Le Boutillier, N. and Selly, R. 2018. Cobalt mineralisation in Cornwall – A new discovery at Porthtowan. Geoscience in South-West England, 14, 176–187. Although cobalt mineralisation has been noted in Cornwall and Devon in the mining literature, there are limited details of its production and paragenesis; detailed mineral studies of cobalt are almost non-existent. This paper describes in detail previously unrecorded cobalt mineralisation discovered at Porthtowan, Cornwall, in the vicinity of old workings which are part of the Wheal Lushington group of mines, immediately west of the village. A small number of massive sulphide/gangue samples (taken from a larger sample suite) were chosen to be as representative as possible. Analysis was carried out using a QEMSCAN® automated mineral SEM-EDS system, which found that samples contained up to 50% cobaltite, along with chalcopyrite, bornite, galena, sphalerite, acanthite, erythrite, matildite, chlorargyite and other primary and secondary mineral species. This assemblage is typical of a sub-type of crosscourse mineralisation, with secondary species a result of significant weathering and supergene alteration, complicated by seawater infiltration due to the coastal location. While the number of samples is limited, the detail of the mineralogical assemblage is significant, as it is the first time such an assemblage has been subjected to this level of scientific scrutiny in Cornwall. 1 Camborne School of Mines, University of Exeter, Cornwall Campus, Penryn, Cornwall, TR10 9FE, UK. -

ERDF Convergence Progress Report, Jun 2014 DRAFT.Pub

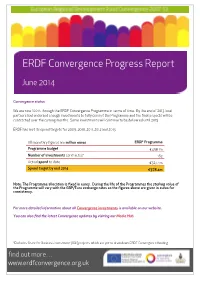

ERDF Convergence Progress Report June 2014 Convergence status We are now 100% through the ERDF Convergence Programme in terms of time. By the end of 2013 local partners had endorsed enough investments to fully commit the Programme and the final projects will be contracted over the coming months. Some investments will continue to be delivered until 2015. ERDF has met its spend targets for 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012 and 2013. All monetary figures are million euros ERDF Programme Programme budget €458.1m Number of investments contracted* 163 Actual spend to date €327.4m Spend target by end 2014 €378.4m Note: The Programme allocation is fixed in euros. During the life of the Programmes the sterling value of the Programme will vary with the GBP/Euro exchange rates so the figures above are given in euros for consistency. For more detailed information about all Convergence investments is available on our website. You can also find the latest Convergence updates by visiting our Media Hub. *Excludes Grant for Business Investment (GBI) projects which are yet to draw down ERDF Convergence funding. find out more… www.erdfconvergence.org.uk CONVERGENCE INVESTMENTS New Investments Apple Aviation Ltd Apple Aviation, an aircraft maintenance, repair and overhaul company, has established a base at Newquay Airport’s Aerohub. Convergence funding from the Grant for Business Investment programme will contribute to salary costs for thirteen new jobs in the business. ERDF Convergence investment: £211,641 (through the GBI SIF) Green Build Hub Located alongside the Eden Project, the Green Build Hub will be a research facility capable of demonstrating and testing the performance of innovative sustainable construction techniques and materials in a real building setting. -

The UK's Evolving Human Landscape

The UK’s Evolving Human Landscape Knowledge checklist Key ideas How secure is my knowledge? . Population, economic activities and settlements are key elements of the human landscape and the UK is closely linked to the wider world - Differences between urban core and rural and how UK and EU government policies have attempted to reduce - Why national and international migration over the past 50 years has altered the population geography of the UK and how UK and EU immigration policy has contributed to increasing ethnic and cultural diversity - Why the decline in primary and secondary sectors and the rise of the tertiary and quaternary sectors in urban and rural areas has altered economic and employment structure in contrasting regions of the UK - Why globalisation, free-trade polices (UK and EU) and privatisation has increased foreign direct investment (FDI) and the role of TNCs in the UK economy The context of the city influences its functions and structure, employment, services and opportunities. Further, how the area is improving and also detached from rural areas - Significance of site, situation and connectivity of the city in a national, regional and global context - The city’s structure (Central Business District (CBD), inner city, suburbs, urban-rural fringe), in terms of its functions and variations in building age and density, land-use and environmental quality - Causes of national and international migration that influence growth and character the different parts of the city - Reasons for different levels of inequality, in employment -

South West West

SouthSouth West West Berwick-upon-Tweed Lindisfarne Castle Giant’s Causeway Carrick-a-Rede Cragside Downhill Coleraine Demesne and Hezlett House Morpeth Wallington LONDONDERRY Blyth Seaton Delaval Hall Whitley Bay Tynemouth Newcastle Upon Tyne M2 Souter Lighthouse Jarrow and The Leas Ballymena Cherryburn Gateshead Gray’s Printing Larne Gibside Sunderland Press Carlisle Consett Washington Old Hall Houghton le Spring M22 Patterson’s M6 Springhill Spade Mill Carrickfergus Durham M2 Newtownabbey Brandon Peterlee Wellbrook Cookstown Bangor Beetling Mill Wordsworth House Spennymoor Divis and the A1(M) Hartlepool BELFAST Black Mountain Newtownards Workington Bishop Auckland Mount Aira Force Appleby-in- Redcar and Ullswater Westmorland Stewart Stockton- Middlesbrough M1 Whitehaven on-Tees The Argory Strangford Ormesby Hall Craigavon Lough Darlington Ardress House Rowallane Sticklebarn and Whitby Castle Portadown Garden The Langdales Coole Castle Armagh Ward Wray Castle Florence Court Beatrix Potter Gallery M6 and Hawkshead Murlough Northallerton Crom Steam Yacht Gondola Hill Top Kendal Hawes Rievaulx Scarborough Sizergh Terrace Newry Nunnington Hall Ulverston Ripon Barrow-in-Furness Bridlington Fountains Abbey A1(M) Morecambe Lancaster Knaresborough Beningbrough Hall M6 Harrogate York Skipton Treasurer’s House Fleetwood Ilkley Middlethorpe Hall Keighley Yeadon Tadcaster Clitheroe Colne Beverley East Riddlesden Hall Shipley Blackpool Gawthorpe Hall Nelson Leeds Garforth M55 Selby Preston Burnley M621 Kingston Upon Hull M65 Accrington Bradford M62