Genetic Variation and Bill Size Dimorphism in a Passerine Bird, the Reed Bunting Emberiza Schoeniclus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Quarterly Journal of Oregon Field Ornithology

$4.95 The quarterly journal of Oregon field ornithology Volume 20, Number 4, Winter 1994 Oregon's First Verified Rustic Bunting 111 Paul Sherrell The Records of the Oregon Bird Records Committee, 1993-1994 113 Harry Nehls Oregon's Next First State Record Bird 115 Bill Tice What will be Oregon's next state record bird?.. 118 Bill Tice Third Specimen of Nuttall's Woodpecker {Picoides nuttallit) in Oregon from Jackson County and Comments on Earlier Records ..119 M. Ralph Browning Stephen P. Cross Identifying Long-billed Curlews Along the Oregon Coast: A Caution 121 Range D. Bayer Birders Add Dollars to Local Economy 122 Douglas Staller Where do chickadees get fur for their nests? 122 Dennis P. Vroman North American Migration Count 123 Pat French Some Thoughts on Acorn Woodpeckers in Oregon 124 George A. Jobanek NEWS AND NOTES OB 20(4) 128 FIELDNOTES. .131 Eastern Oregon, Spring 1994 131 Steve Summers Western Oregon, Spring 1994 137 Gerard Lillie Western Oregon, Winter 1993-94 143 Supplement to OB 20(3): 104, Fall 1994 Jim Johnson COVER PHOTO Clark's Nutcracker at Crater Lake, 17 April 1994. Photo/Skip Russell. CENTER OFO membership form OFO Bookcase Complete checklist of Oregon birds Oregon s Christmas Bird Counts Oregon Birds is looking for material in these categories: Oregon Birds News Briefs on things of temporal importance, such as meetings, birding trips, The quarterly journal of Oregon field ornithology announcements, news items, etc. Articles are longer contributions dealing with identification, distribution, ecology, is a quarterly publication of Oregon Field OREGON BIRDS management, conservation, taxonomy, Ornithologists, an Oregon not-for-profit corporation. -

01 Grant 1-12.Qxd

COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Peter R. Grant & B. Rosemary Grant: How and Why Species Multiply is published by Princeton University Press and copyrighted, © 2007, by Princeton University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher, except for reading and browsing via the World Wide Web. Users are not permitted to mount this file on any network servers. Follow links for Class Use and other Permissions. For more information send email to: [email protected] CHAPTER ONE The Biodiversity Problem and Darwin’s Finches Now it is a well-known principle of zoological evolution that an isolated region, if large and sufficiently varied in topography, soil, climate and vegetation, will give rise to a diversified fauna according to the law of adaptive radiation from primitive and central types. Branches will spring off in all directions to take advantage of every possible opportunity of securing foods. (Osborn 1900, p. 563) I have stated that in the thirteen species of ground-finches, a nearly perfect gradation may be traced, from a beak extraordinarily thick, to one so fine, that it may be compared to that of a warbler. (Darwin 1839, p. 475) Biodiversity e live in a world so rich in species we do not know how many there are. Adding up every one we know, from influenza viruses Wto elephants, we reach a total of a million and a half (Wilson 1992, ch. 8). The real number is almost certainly at least five million, perhaps ten or even twenty, and although very large it is a small fraction of those that have ever existed; the vast majority has become extinct. -

Striking Difference in Response to Expanding Brood Parasites by Birds in Western and Eastern Beringia

J. Field Ornithol. 0(0):1–9, 2018 DOI: 10.1111/jofo.12247 Striking difference in response to expanding brood parasites by birds in western and eastern Beringia Vladimir Dinets,1,2,7 Kristaps Sokolovskis,3,4 Daniel Hanley,5 and Mark E. Hauber6 1Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology, Tancha 1919-1, Onna-son, Okinawa 904-0497, Japan 2Psychology Department, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996, USA 3Molecular Ecology and Evolution Lab, Lund University, S€olvegatan 37, Lund 223 62, Sweden 4Evolutionary Biology Center, Uppsala University, Norbyvagen€ 14D, Uppsala 752 36, Sweden 5Department of Biology, Long Island University – Post, Brookville, New York 11548, USA 6Department of Animal Biology, School of Integrative Biology, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, Illinois 61801, USA Received 30 November 2017; accepted 8 March 2018 ABSTRACT. Two species of obligate brood-parasitic Cuculus cuckoos are expanding their ranges in Beringia. Both now breed on the Asian side, close to the Bering Strait, and are found in Alaska during the breeding season. From May to July 2017, we used painted 3D-printed model eggs of two cuckoo host-races breeding in northeastern Siberia to test behavioral responses of native songbirds on both sides of the Bering Strait, with particular attention to species that are known cuckoo hosts in their Siberian range. Each host nest was tested after the second egg was laid and, if possible, again 4 days later with a model of a different type. Although our Siberian study site was also outside the known breeding ranges of the cuckoos, we found that Siberian birds had strong anti-parasite responses, with 14 of 22 models rejected. -

Diving Times of Grebes and Masked Ducks

April 1974] GeneralNotes 415 We wish to thank Dean Amadon of the American Museum of Natural History; Marshall Howe of the Bird and Mammal Laboratories, National Museum of Natural History; Oliver L. Austin, Jr. of the Florida State Museum; and Dwain W. Warner of the Bell Museum of Natural History, University of Minnesota, for providing specimensfor examination. Observationsand measurementswere made while conductinga study of wintering Common Loons funded in part by the Zoology Department of the University of Minnesota. William D. Schmid and Dwain W. Warner provided help with the manuscript. L•rERArURE CITED BI.rCKI.E¾, P.A. 1972. The changingseason. Amer. Birds 26: 574. CARLSOn,C. W. 1971. Arctic Loon at Ocean City, Maryland. Maryland Birdlife 27: 68-72. Gmsco•r, L. 1943. Notes on the Pacific Loons. Bull. MassachusettsAudubon Soc. 27: 106-109. PAL•rEa, R. S. 1962. Handbook of North American birds. New Haven, Con- necticut, Yale Univ. Press. Po•ra•r, R.H. 1951. Audubon water bird guide. Garden City, New York, Double- day and Co. ROBBINS,C., B. Ba•nJ•, ^•) H. S. Z•r. 1966. Birds of North America. New York, Golden Press. W•x•r•m•¾,H. F. (Ed.). 1940. The handbookof British birds. London, Witherby, Ltd. A•r•ro•¾ E..McI•r¾• and Jm)•r•r W. McintYre, Department ot Zoology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, $.•455. Accepted 30 May 73. Diving times of grebes and Masked Ducks.--Least Grebes (Podiceps dominicus)and Masked Ducks (Oxyura dominica) were found to have significantly different diving times at a small pond near Turrialba, Costa Rica in 1963 (Jenni 1969, Auk 86: 355). -

A Little Bunting Reaches Baja California Sur KURT A

NOTES A LITTLE BUNTING REACHES BAJA CALIFORNIA SUR KURT A. RADAMAKER, 8741 E. San Pedro Dr., Scottsdale, Arizona 85258; [email protected] DAVID J. POWELL, 11001 N. 7th St., #1184, Phoenix, Arizona 85020; [email protected] At midday on 8 October 2008, we discovered a Little Bunting (Emberiza pusilla) at Rancho San José de Castro on the Vizcaíno Peninsula, Baja California Sur (cover photo, Figure 1). This sighting represents the first record of this Old World species from Mexico and only the third for North America south of Alaska. Rancho San José de Castro is located at 27° 32′ 20.83″ N, 114° 28′ 24.29″ W, approximately 3 km toward Bahía Asunción south of the main road from Ejido Viz- caíno to Bahía Tortugas. The ranch consists of a few small structures and dwellings, a small livestock pen, a natural spring and a pond about 50 m wide, an orchard, and several large trees and plantings. It is one of several small ranches that dot the immense, xeric landscape of the Vizcaíno Peninsula, a rugged and barren promon- tory jutting far out into the Pacific Ocean about midway down the Baja California Peninsula, south and west of Guerrero Negro. Its proximity to the ocean, isolation, and barren landscape, with only a few remote ranches and fishing villages, make it an ideal location for finding migrants and vagrants (Howell et al. 2001). Ever since the discovery of Mexico’s first Arctic Warbler (Phylloscopus borealis) there (Pyle and Howell (1993), it has been birded nearly annually, producing a number of noteworthy sightings (1991–2000 results summarized by Erickson and Howell 2001). -

1 SOUTH KOREA 22 October – 3 November, 2018

SOUTH KOREA 22 October – 3 November, 2018 Sandy Darling, Jeni Darling, Tom Thomas Most tours to South Korea occur in May for the spring migration or in late fall or winter for northern birds that winter in South Korea. This trip was timed in late October and early November to try see both summer residents and winter arrivals, and was successful in doing so. Birds were much shyer than in North America and often were visible only briefly, so that, for example, we saw few thrushes although they could be heard. This report has been written by Sandy and includes photos from both Tom (TT) and Sandy (SD). Sandy saw 166 species adequately of which 57 were life birds. When one includes birds heard, seen by the leader or others, or not seen well enough to count (BVD), the total was about 184. From trip reports it was clear that the person to lead the tour was Dr Nial Moores, Director of Birds Korea, an NGO working to improve the environment, especially for birds, in Korea. Nial has twenty years of experience in Korea, knows where birds are, and has ears and eyes that are exceptional. He planned the trip, made all the arrangements, found birds that we would not have found on our own and was our interface with Koreans, few of whom speak English. Nial also had to rejig the itinerary when strong winds led to the cancellation of a ferry to Baekryeong Island. We drove the vehicles - confidence was needed in dealing with city traffic, which was as aggressive as other trip reports said! Some of the highlights of the trip were: About 40,000 massed shore birds on Yubu Island, including the rare Spoonbill Sandpiper, a life bird for Tom. -

Occurrence and Breeding of the Little Bunting Emberiza Pusilla in Kuusamo (NE Finland)

Occurrence and breeding of the Little Bunting Emberiza pusilla in Kuusamo (NE Finland) P. KOIVUNEN, E. S. NYHOLM and S. SULKAVA KoIVUNEN, P. [Kirkkotie 4, SF-93600 Kuusamo], NYHOLM, E. S. [Kp. 6, SF-93600 Kuusamo] and SULKAVA, S. [Department of Zoology, University of Oulu, SF-90100 Oulu 10] . 1975. - Occurrence and breeding of the Little Bunting Emberiza pusilla in Kuusamo . Ornis Fenn . 52:85-96. The Little Buntings arrive in Kuusamo (NE Finland) on an average on June 6. In warm springs, the time of arrival is earlier and the number of individuals settling down in the area is greater. Laying begins on an average on June 11, but the date varies, depending on the time of arrival. A second brood is often produced in July. The eggs are of two colour types . The breeding result is good: 76 % of the eggs pro- duced young leaving the nest. The Little Buntings bred in three different habitats, pine peat bogs, shore meadows with willows (fens), and moist birch forests. The vegetation cover above the nest was mostly 100 %. The nest cup was lined with dry leaves of Festuca ovina. The first records of the breeding of the The records for 1971-72 are still Little Bunting, Emberiza pusilla Pall ., more restricted (HILDEN 1973) . from the years 1935 in Finland are Until now, knowledge of the breeding (PALMGREN 1936) and 1942 (KIVIRIKKO number of records biology of the Little Bunting has been 1947), and, since the based on observations made at single grown, the species is presumably still has nests (ANDERSSON 1968, DEMENT'EV et increasing in the westernmost part of its al. -

Wildlife List Voyage # 1223 Birding the Russian Far East 27Th May - 8Th June 2012

Wildlife List Voyage # 1223 Birding the Russian Far East 27th May - 8th June 2012 © K Ovsyanikova 53b Montreal Street, PO Box 7218, Christchurch, New Zealand. Tel: +64 3 365 3500 / Fax: +64 3 365 1300 Freephone (within NZ): 0800 262 8873 [email protected] / www.heritage-expeditions.com Oceanodroma castro Swinhoes Storm Petrel Oceanodroma leucorhoa Leach’s StormPetrel Puffinus tenuirostris Short-tailed Shearwater Puffinus griseus Sooty Shearwater Puffinus carneipes Flesh-footed Shearwater Calonectris leucomelas Streaked Shearwater Pterodroma inexpectata Mottled Petrel Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar Phoebastria nigripes Black-footed Albatross Phoebastria immutablis Laysan Albatross Phoebastria albatrus Short-Tailed Albatross Podiceps nigricollis Black-necked Grebe(EaredGrebe) Podiceps grisegena Red-necked Grebe Podiceps auritus Slavonian Grebe(HornedGrebe) Gavia stellata Red-throated Diver(Red-throatedLoon) Gavia pacifica Pacific Diver(PacificLoon) Gavia arctica Black-throated Diver(ArcticLoon) Gavia adamsii White-billed Diver(Yellow-billedLoon) Puffinus bulleri Bullers Shearwater RUSSIAN FAREASTSPECIESLIST RUSSIAN FAREASTSPECIESLIST RUSSIAN FAREASTSPECIESLIST RUSSIAN FAREASTSPECIESLIST SPECIES SPECIES SPECIES SPECIES ABBCABDD Day 1 A 4 1 1 4 B 2 A 5 A 1 2 A 1 5Day 2 2 Day 3 1Day 1 4 A Day 5 Day 6 A A 1 Day 7 A A 1 Day 8 A CBBB 1 Day 9 Day 10 1 1 Day 11 D Day 12 Day 13 Day 14 Day 15 Day 16 Day 17 Day 18 RUSSIAN FAR EAST SPECIES LIST Fork-tailed Storm Petrel C 5 4B A 2 A 5 Oceanodroma monorhis Band-rumped Storm Petrel Oceanodroma -

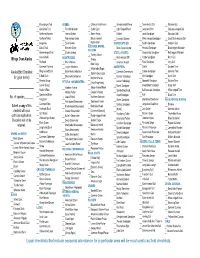

Wings Over Alaska Checklist

Blue-winged Teal GREBES a Chinese Pond-Heron Semipalmated Plover c Temminck's Stint c Western Gull c Cinnamon Teal r Pied-billed Grebe c Cattle Egret c Little Ringed Plover r Long-toed Stint Glacuous-winged Gull Northern Shoveler Horned Grebe a Green Heron Killdeer Least Sandpiper Glaucous Gull Northern Pintail Red-necked Grebe Black-crowned r White-rumped Sandpiper a Great Black-backed Gull a r Eurasian Dotterel c Garganey a Eared Grebe Night-Heron OYSTERCATCHER Baird's Sandpiper Sabine's Gull c Baikal Teal Western Grebe VULTURES, HAWKS, Black Oystercatcher Pectoral Sandpiper Black-legged Kittiwake FALCONS Green-winged Teal [Clark's Grebe] STILTS, AVOCETS Sharp-tailed Sandpiper Red-legged Kittiwake c Turkey Vulture Canvasback a Black-winged Stilt a Purple Sandpiper Ross' Gull Wings Over Alaska ALBATROSSES Osprey Redhead a Shy Albatross a American Avocet Rock Sandpiper Ivory Gull Bald Eagle c Common Pochard Laysan Albatross SANDPIPERS Dunlin r Caspian Tern c White-tailed Eagle Ring-necked Duck Black-footed Albatross r Common Greenshank c Curlew Sandpiper r Common Tern Alaska Bird Checklist c Steller's Sea-Eagle r Tufted Duck Short-tailed Albatross Greater Yellowlegs Stilt Sandpiper Arctic Tern for (your name) Northern Harrier Greater Scaup Lesser Yellowlegs c Spoonbill Sandpiper Aleutian Tern PETRELS, SHEARWATERS [Gray Frog-Hawk] Lesser Scaup a Marsh Sandpiper c Broad-billed Sandpiper a Sooty Tern Northern Fulmar Sharp-shinned Hawk Steller's Eider c Spotted Redshank Buff-breasted Sandpiper c White-winged Tern Mottled Petrel [Cooper's -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION. -

Red List of Bangladesh 2015

Red List of Bangladesh Volume 1: Summary Chief National Technical Expert Mohammad Ali Reza Khan Technical Coordinator Mohammad Shahad Mahabub Chowdhury IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature Bangladesh Country Office 2015 i The designation of geographical entitles in this book and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature concerning the legal status of any country, territory, administration, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The biodiversity database and views expressed in this publication are not necessarily reflect those of IUCN, Bangladesh Forest Department and The World Bank. This publication has been made possible because of the funding received from The World Bank through Bangladesh Forest Department to implement the subproject entitled ‘Updating Species Red List of Bangladesh’ under the ‘Strengthening Regional Cooperation for Wildlife Protection (SRCWP)’ Project. Published by: IUCN Bangladesh Country Office Copyright: © 2015 Bangladesh Forest Department and IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holders, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holders. Citation: Of this volume IUCN Bangladesh. 2015. Red List of Bangladesh Volume 1: Summary. IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, Bangladesh Country Office, Dhaka, Bangladesh, pp. xvi+122. ISBN: 978-984-34-0733-7 Publication Assistant: Sheikh Asaduzzaman Design and Printed by: Progressive Printers Pvt. -

Bio 209 Course Title: Chordates

BIO 209 CHORDATES NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA SCHOOL OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY COURSE CODE: BIO 209 COURSE TITLE: CHORDATES 136 BIO 209 MODULE 4 MAIN COURSE CONTENTS PAGE MODULE 1 INTRODUCTION TO CHORDATES…. 1 Unit 1 General Characteristics of Chordates………… 1 Unit 2 Classification of Chordates…………………... 6 Unit 3 Hemichordata………………………………… 12 Unit 4 Urochordata………………………………….. 18 Unit 5 Cephalochordata……………………………... 26 MODULE 2 VERTEBRATE CHORDATES (I)……... 31 Unit 1 Vertebrata…………………………………….. 31 Unit 2 Gnathostomata……………………………….. 39 Unit 3 Amphibia…………………………………….. 45 Unit 4 Reptilia……………………………………….. 53 Unit 5 Aves (I)………………………………………. 66 Unit 6 Aves (II)……………………………………… 76 MODULE 3 VERTEBRATE CHORDATES (II)……. 90 Unit 1 Mammalia……………………………………. 90 Unit 2 Eutherians: Proboscidea, Sirenia, Carnivora… 100 Unit 3 Eutherians: Edentata, Artiodactyla, Cetacea… 108 Unit 4 Eutherians: Perissodactyla, Chiroptera, Insectivora…………………………………… 116 Unit 5 Eutherians: Rodentia, Lagomorpha, Primata… 124 MODULE 4 EVOLUTION, ADAPTIVE RADIATION AND ZOOGEOGRAPHY………………. 136 Unit 1 Evolution of Chordates……………………… 136 Unit 2 Adaptive Radiation of Chordates……………. 144 Unit 3 Zoogeography of the Nearctic and Neotropical Regions………………………………………. 149 Unit 4 Zoogeography of the Palaearctic and Afrotropical Regions………………………………………. 155 Unit 5 Zoogeography of the Oriental and Australasian Regions………………………………………. 160 137 BIO 209 CHORDATES COURSE GUIDE BIO 209 CHORDATES Course Team Prof. Ishaya H. Nock (Course Developer/Writer) - ABU, Zaria Prof. T. O. L. Aken’Ova (Course