Yellowstone Science a Quarterly Publication Devoted to the Natural and Cultural Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November 2020- January 2021

AMERICAN LEGION DEPARTMENT OF MONTANA Non-Profit Org. ARMED FORCES RESERVE CENTER U.S. Postage P.O. BOX 6075 HELENA, MT 59604-6075 PAID Permit No. 189 Helena, MT 59601 Volume 98, No. 2 November 2020— January 2021 RAYMOND J NYDEGGER Important Upcoming Dates Nov 11 ........................... Veterans Day DEPARTMENT COMMANDER 1975-76 Nov 26 ........................... Thanksgiving Raymond J Nydegger, Depart- Ray was very civic minded, he Dec 7 .......................Pearl Harbor Day ment Commander 1975-76 of belonged to the Masons, Eastern Dec 9 .....................75% Target Date – Renewal Cut Off Date Melstone, a 65-year member of Star and Shrine; he was also Dec 11 .................................Hanukkah Townsend Post 42 passed away on a former Dad Advisor for the Dec 15 .............. All Employer Awards August 18, 2020. Ray served in the DeMolay and a former Mayor of due to Department US Navy aboard the AE4 USS MT Townsend. Dec 25 ............................... Christmas Baker, an ammunition ship, during Dec 26 .........All 2021 Cash Calendars Ray is survived by his wife due back to Department the Korean War. Jeanne of Melstone, who served Jan 1 ................. New Year’s Day 2021 Ray held all elected offices of the as the Department Auxiliary Jan 2 ..........First 2021 Big K Drawings Post and District; additionally, he President the same year Ray was First 2021 Cash Calendar held many of the appointed offices drawings Commander; and his daughters, Jan 5 ...........................MT Legionnaire in both the Post and District. At Jennifer Bergin and Jody Haa- Feb / Mar / Apr issue cutoff date the Department level he served as gland; and son John. -

Thomas Stuart Homestead Site: Historic Context Report

Thomas Stuart Homestead Historic Context Report Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site Avana Andrade Public Lands History Center at Colorado State University 2/1/2012 1 Thomas Stuart Homestead Site: Historic Context Report Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site in Deer Lodge Montana is currently developing plans for a new contact station. One potential location will affect the site of a late-nineteenth-century historic homestead. Accordingly, the National Park Service and the Montana State Historic Preservation Office need more information about the historic importance of the Thomas Stuart homestead site to determine future decisions concerning the contact station. The following report provides the historic contexts within which to assess the resource’s historic significance according to National Register of Historic Places guidelines. The report examines the site’s association with Thomas Stuart, a Deer Lodge pioneer, and the Menards, a French- Canadian family, and presents the wider historical context of the fur trade, Deer Lodge’s mixed cultural milieu, and the community’s transformation into a settled, agrarian town. Though only indications of foundations and other site features remain at the homestead, the report seeks to give the most complete picture of the site’s history. Site Significance and Integrity The Thomas Stuart homestead site is evaluated according to the National Register of Historic Places, a program designed in the 1960s to provide a comprehensive listing of the United States’ significant historic properties. Listing on the National Register officially verifies a site’s importance and requires park administrators or land managers to consider the significance of the property when planning federally funded projects. -

Recreational Trails Master Plan

Beaverhead County Recreational Trails Master Plan Prepared by: Beaverhead County Recreational Trails Master Plan Prepared for: Beaverhead County Beaverhead County Commissioners 2 South Pacific Dillon, MT 59725 Prepared by: WWC Engineering 1275 Maple Street, Suite F Helena, MT 59601 (406) 443-3962 Fax: (406) 449-0056 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ...................................................................................................... 1 Overview ...................................................................................................................... 1 Public Involvement .................................................................................................... 1 Key Components of the Plan ..................................................................................... 1 Intent of the Plan ....................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1 - Master Plan Overview................................................................................ 3 1.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 3 1.1.1 Project Location ............................................................................................... 3 1.2 Project Goals ......................................................................................................... 3 1.2.1 Variety of Uses ................................................................................................ -

East Bench Unit History

East Bench Unit Three Forks Division Pick Sloan Missouri Basin Program Jedediah S. Rogers Bureau of Reclamation 2008 Table of Contents East Bench Unit...............................................................2 Pick Sloan Missouri Basin Program .........................................2 Project Location.........................................................2 Historic Setting .........................................................3 Investigations...........................................................7 Project Authorization....................................................10 Construction History ....................................................10 Post Construction History ................................................15 Settlement of Project Lands ...............................................19 Project Benefits and Uses of Project Water...................................20 Conclusion............................................................21 Bibliography ................................................................23 Archival Sources .......................................................23 Government Documents .................................................23 Books ................................................................24 Other Sources..........................................................24 1 East Bench Unit Pick Sloan Missouri Basin Program Located in rural southwest Montana, the East Bench Unit of the Pick Sloan Missouri Basin Program provides water to 21,800 acres along the Beaverhead River in -

A HISTORY OP FORT SHAW, MONTANA, from 1867 to 1892. by ANNE M. DIEKHANS SUBMITTED in PARTIAL FULFILLMENT of "CUM LAUDE"

A HISTORY OP FORT SHAW, MONTANA, FROM 1867 TO 1892. by ANNE M. DIEKHANS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF "CUM LAUDE" RECOGNITION to the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY CARROLL COLLEGE 1959 CARROLL COLLEGE LIBRARY HELENA, MONTANA MONTANA COLLECTION CARROLL COLLEGE LIBRAS/- &-I THIS THESIS FOR "CUM LAUDE RECOGNITION BY ANNE M. DIEKHANS HAS BEEN APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY Date ii PREFACE Fort Shaw existed as a military post between the years of 1867 and 1892. The purpose of this thesis is to present the history of the post in its military aspects during that period. Other aspects are included but the emphasis is on the function of Fort Shaw as district headquarters of the United States Army in Montana Territory. I would like to thank all those who assisted me in any way in the writing of this thesis. I especially want to thank Miss Virginia Walton of the Montana Historical Society and the Rev. John McCarthy of the Carroll faculty for their aid and advice in the writing of this thesis. For techni cal advice I am indebted to Sister Mary Ambrosia of the Eng lish department at Carroll College. I also wish to thank the Rev. James R. White# Mr. Thomas A. Clinch, and Mr. Rich ard Duffy who assisted with advice and pictures. Thank you is also in order to Mrs. Shirley Coggeshall of Helena who typed the manuscript. A.M.D. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chggter Page I. GENERAL BACKGROUND............................... 1 II. MILITARY ACTIVITIES............................. 14 Baker Massacre Sioux Campaign The Big Hole Policing Duties Escort and Patrol Duties III. -

The 1988 Yellowstone Fires: the Response of the Elk And

THE 1988 YELLOWSTONE FIRES: THE RESPONSE OF THE ELK AND BISON C'0\1\fC!\ITY by Tanya C. Apple A SENIOR THESIS m GENERAL STUDIES Submmited to the General Studies Council in the College of Arts and Sciences at Texas Tech University in Partial fulfillment for the Requirements for the Degree of BACHELOR OF GENERAL STUDIES Approved DR. ROB MITCHELL Department ofRange, Wildlife, and Fisheries Management Chairperson of Thesis Committee DR. JEFF LEE Department of Geography Assistant Director, Fire Man ent U.S.D.A. Forestry Service, Region III 1 0 •. DALE DAVIS Director of General Studies August 1998 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my thanks to many people for their help and support in my pursuit of my education and the production of this paper. 1 am grateful to Dr. Dale Davis for his leadership in the General Studies Program. A special thanks goes out to each member of my committee: Dr. Jeff Lee of the Geography Department for his input and time; Mr. Ronny Moody for his expertise, enthusiasm, and support; and Dr. Rob Mitchell for being the chan of my committee and for the time he sacrificed to help me. I would also like to thank Ms. Linda Gregston for being my advocate and one of my strongest supporters. Lastly, I would like to thank my husband. Ken, and the rest of my family for having the patience and faith that I would some day complete my degree. n TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii LIST OF TABLES iv CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. A BRIEF HISTORY OF YELLOWSTONE 4 Early Exploration Accounts 4 Establishment of Yellowstone National Park 6 Early Fire Suppression Policy 7 III. -

Appendix I Lunar and Martian Nomenclature

APPENDIX I LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE A large number of names of craters and other features on the Moon and Mars, were accepted by the IAU General Assemblies X (Moscow, 1958), XI (Berkeley, 1961), XII (Hamburg, 1964), XIV (Brighton, 1970), and XV (Sydney, 1973). The names were suggested by the appropriate IAU Commissions (16 and 17). In particular the Lunar names accepted at the XIVth and XVth General Assemblies were recommended by the 'Working Group on Lunar Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr D. H. Menzel. The Martian names were suggested by the 'Working Group on Martian Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr G. de Vaucouleurs. At the XVth General Assembly a new 'Working Group on Planetary System Nomenclature' was formed (Chairman: Dr P. M. Millman) comprising various Task Groups, one for each particular subject. For further references see: [AU Trans. X, 259-263, 1960; XIB, 236-238, 1962; Xlffi, 203-204, 1966; xnffi, 99-105, 1968; XIVB, 63, 129, 139, 1971; Space Sci. Rev. 12, 136-186, 1971. Because at the recent General Assemblies some small changes, or corrections, were made, the complete list of Lunar and Martian Topographic Features is published here. Table 1 Lunar Craters Abbe 58S,174E Balboa 19N,83W Abbot 6N,55E Baldet 54S, 151W Abel 34S,85E Balmer 20S,70E Abul Wafa 2N,ll7E Banachiewicz 5N,80E Adams 32S,69E Banting 26N,16E Aitken 17S,173E Barbier 248, 158E AI-Biruni 18N,93E Barnard 30S,86E Alden 24S, lllE Barringer 29S,151W Aldrin I.4N,22.1E Bartels 24N,90W Alekhin 68S,131W Becquerei -

The Settlement of Teton Valley, Idaho-Wyoming

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1974 The Settlement of Teton Valley, Idaho-Wyoming David Brooks Green Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons, Mormon Studies Commons, and the Sociology Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Green, David Brooks, "The Settlement of Teton Valley, Idaho-Wyoming" (1974). Theses and Dissertations. 4727. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4727 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE sfttiinhsettlementT OF TETtemonTETONON VALLEY IDAHO WYOMING A thesis presented to the department of geography brighamB r ighambigham young university in partial fulfillmentfulfillynent of the requirements for the degree master of science by D brooks green this thesis by D brooks green is accepted in its present form by the department of geography of brigham young university as satisfying the thesis requirement for the degree of master of science 1 1 L waw& eiaelaLIA X 1 1 X y richardurfaH jackson cammicommiconmiiuteewae3e chairman 1 L AAAy L 1 1 i yuj alan H grey committecommittee meermepioer te aa7aaa roberi 1 lilILL a on depai6twnt rronaron 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS page PREFACE 0 0 0 0 0 0 viii LIST OF TABLES v LIST OF illustrations vi chapter I1 introduction -

Architecture of Yellowstone a Microcosm of American Design by Rodd L

Architecture of Yellowstone A Microcosm of American Design by Rodd L. Wheaton The idea of Yellowstone lands. The army’s effort be- National Park—the preser- gan from the newly estab- vation of exotic wilderness— lished Camp Sheridan, con- was a noble experiment in structed below Capitol Hill 1872. Preserving nature and at the base of the lower ter- then interpreting it to the park races at Mammoth Hot visitors over the last 125 years Springs. has manifested itself in many Beyond management management strategies. The difficulties, the search for an few employees hired by the architectural style had be- Department of the Interior, gun. The Northern Pacific then the U.S. Army cavalry- Railroad, which spanned men, and, after 1916, the Montana, reached Cinnabar rangers of the National Park with a spur line by Septem- Service needed shelter; ber 1883. The direct result of hence, the need for architec- this event was the introduc- ture. Whether for the pur- tion of new architectural pose of administration, em- styles to Yellowstone Na- ployee housing, mainte- tional Park. The park’s pio- nance, or visitor accommo- neer era faded with the ad- dation, the architecture of vent of the Queen Anne style Yellowstone has proven that that had rapidly reached its construction in the wilder- zenith in Montana mining ness can be as exotic as the The burled logs of Old Faithful’s Lower Hamilton Store epitomize the communities such as Helena landscape itself and as var- Stick style. NPS photo. and Butte. In Yellowstone ied as the whims of those in the style spread throughout charge. -

Carnegie Institution of Washington Monograph Series

BTILL UMI Carnegie Institution of Washington Monograph Series BT ILL UMI 1 The Carnegie Institution of Washington, D. C. 1902. Octavo, 16 pp. 2 The Carnegie Institution of Washington, D. C. Articles of Incorporation, Deed of Trust, etc. 1902. Octavo, 15 pp. 3 The Carnegie Institution of Washington, D. C. Proceedings of the Board of Trustees, January, 1902. 1902. Octavo, 15 pp. 4 CONARD, HENRY S. The Waterlilies: A Monograph of the Genus Nymphaea. 1905. Quarto, [1] + xiii + 279 pp., 30 pls., 82 figs. 5 BURNHAM, S. W. A General Catalogue of Double Stars within 121° of the North Pole. 1906. Quarto. Part I. The Catalogue. pp. [2] + lv + 1–256r. Part II. Notes to the Catalogue. pp. viii + 257–1086. 6 COVILLE, FREDERICK VERNON, and DANIEL TREMBLY MACDOUGAL. Desert Botani- cal Laboratory of the Carnegie Institution. 1903. Octavo, vi + 58 pp., 29 pls., 4 figs. 7 RICHARDS, THEODORE WILLIAM, and WILFRED NEWSOME STULL. New Method for Determining Compressibility. 1903. Octavo, 45 pp., 5 figs. 8 FARLOW, WILLIAM G. Bibliographical Index of North American Fungi. Vol. 1, Part 1. Abrothallus to Badhamia. 1905. Octavo, xxxv + 312 pp. 9 HILL, GEORGE WILLIAM, The Collected Mathematical Works of. Quarto. Vol. I. With introduction by H. POINCARÉ. 1905. xix + 363 pp. +errata, frontispiece. Vol. II. 1906. vii + 339 pp. + errata. Vol. III. 1906. iv + 577 pp. Vol. IV. 1907. vi + 460 pp. 10 NEWCOMB, SIMON. On the Position of the Galactic and Other Principal Planes toward Which the Stars Tend to Crowd. (Contributions to Stellar Statistics, First Paper.) 1904. Quarto, ii + 32 pp. -

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America There are approximately 101,135sexual abuse claims filed. Of those claims, the Tort Claimants’ Committee estimates that there are approximately 83,807 unique claims if the amended and superseded and multiple claims filed on account of the same survivor are removed. The summary of sexual abuse claims below uses the set of 83,807 of claim for purposes of claims summary below.1 The Tort Claimants’ Committee has broken down the sexual abuse claims in various categories for the purpose of disclosing where and when the sexual abuse claims arose and the identity of certain of the parties that are implicated in the alleged sexual abuse. Attached hereto as Exhibit 1 is a chart that shows the sexual abuse claims broken down by the year in which they first arose. Please note that there approximately 10,500 claims did not provide a date for when the sexual abuse occurred. As a result, those claims have not been assigned a year in which the abuse first arose. Attached hereto as Exhibit 2 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the state or jurisdiction in which they arose. Please note there are approximately 7,186 claims that did not provide a location of abuse. Those claims are reflected by YY or ZZ in the codes used to identify the applicable state or jurisdiction. Those claims have not been assigned a state or other jurisdiction. Attached hereto as Exhibit 3 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the Local Council implicated in the sexual abuse. -

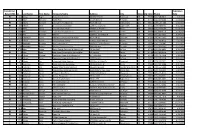

Installers.Pdf

Initial (I) or Expiration Recert (RI) Id Last Name First Sept Name Company Name Address City State Zip Code Phone Date RI 212 Abbas Roger Abbas Construction 6827 NE 33rd St Redmond OR 97756 (541) 548-6812 2/3/2024 I 2888 Adair Benjamin Septic Pros 1751 N Main st Prineville OR 97754 (541) 359-8466 5/10/2024 RI 727 Adams Kenneth Ken Adams Plumbing Inc 906 N 9th Ave Walla Walla WA 99362 (509) 529-7389 6/23/2023 RI 884 Adcock Dean Tri County Construction 22987 SE Dowty Rd Eagle Creek OR 97022 (503) 948-0491 9/25/2023 I 2592 Adelt Georg Cascade Valley Septic 17360 Star Thistle Ln Bend OR 97703 (541) 337-4145 11/18/2022 I 2994 Agee Jetamiah Leavn Trax Excavation LLC 50020 Collar Dr. La Pine OR 97739 (541) 640-3115 9/13/2024 I 2502 Aho Brennon BRX Inc 33887 SE Columbus St Albany OR 97322 (541) 953-7375 6/24/2022 I 2392 Albertson Adam Albertson Construction & Repair 907 N 6th St Lakeview OR 97630 (541) 417-1025 12/3/2021 RI 831 Albion Justin Poe's Backhoe Service 6590 SE Seven Mile Ln Albany OR 97322 (541) 401-8752 7/25/2022 I 2732 Alexander Brandon Blux Excavation LLC 10150 SE Golden Eagle Dr Prineville OR 97754 (541) 233-9682 9/21/2023 RI 144 Alexander Robert Red Hat Construction, Inc. 560 SW B Ave Corvallis OR 97333 (541) 753-2902 2/17/2024 I 2733 Allen Justan South County Concrete & Asphalt, LLC PO Box 2487 La Pine OR 97739 (541) 536-4624 9/21/2023 RI 74 Alley Dale Back Street Construction Corporation PO Box 350 Culver OR 97734 (541) 480-0516 2/17/2024 I 2449 Allison Michael Deschutes Property Solultions, LLC 15751 Park Dr La Pine OR 97739 (541) 241-4298 5/20/2022 I 2448 Allison Tisha Deschutes Property Solultions, LLC 15751 Park Dr La Pine OR 97739 (541) 241-4298 5/20/2022 RI 679 Alman Jay Integrated Water Services 4001 North Valley Dr.