Human Influences on the Northern Yellowstone Range by Ryan M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yellowstone Science a Quarterly Publication Devoted to the Natural and Cultural Resources

Yellowstone Science A quarterly publication devoted to the natural and cultural resources Apollinaris Spring through the Years Lewis & Clark Among the Grizzlies 1960s Winter Atmospheric Research, Part II Wildlife–Human Conflicts Volume 11 Number 1 Labors of Love NG DAN As the new year begins, we commem- promoted the Great Fountain orate the passing of three great friends of Project, an effort that, with the Yellowstone. support of the Yellowstone Park I didn’t know Don White, but his Foundation, mitigated the friends tell me that Don’s testimony before resource impacts on the geyser Congress helped bring geothermal protec- from the adjacent road and tion in Yellowstone into the national con- reduced off-boardwalk travel by sciousness. This, among many other providing more badly needed accomplishments in his career with the viewing space at the popular USGS, noted in this issue by Bob Fournier geyser. John assisted inter- and Patrick Muffler, earn him a place in preters on a daily basis by pro- the history of Yellowstone’s great scien- viding visitors with Old Faith- tists and friends. ful predictions after the visitor I did know Tom Tankersley. I worked center closed. He conducted for him as an interpreter for four years and thermal observations, interpret- I would be honored to be considered one ed geysers to the public, and of his friends. Tom was an excellent inter- was often seen with a hammer preter, a strong manager, and an extraordi- re-nailing thousands of loose nary human being. When I think of him, I boardwalk planks that presented a hazard returning to Yellowstone after 1997, vol- will remember that gleam in his eye when to visitors. -

Location of Legal Description

Form No. 1O-306 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS Historic Resources- of Yellows-tone National Park (Partial Inventory; AND/OR OIC^ON^ Obsidian Cliff Kiosk) LOCATION STREETS NUMBER N/A N/ANOTFOR PUBUCATION CITY. TOWN- ojTfl k-yA^YV*XJL JjU^ CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT N/A iYellows-tonp Naffrynal <p., T4i,_ VICINITY OF At Large STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Wyoming 56 029 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT Z-PUBLIC —OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE. _ MUSEUM X^BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE 2L.UNOCCUPIED _ COMMERCIAL S_PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS _ EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE _ SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT N /IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED _ GOVERNMENT _ SCIENTIFIC multiple —BEING CONSIDERED X-YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION X resource —NO _ MILITARY —OTHER: AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: STRIET& NUMBER .655, Parfet Street. P.0. Box 2.5287 CITY. TOWN STATE Denver VICINITY OF Colorado LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, , REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. H / A STREET & NUMBER Yellowstone National Park CtTY. TOWN STATE Wyoming N/A 01 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE List of Classified Structures Inventory DATE 1976-1977 XFEOEBAL —STATE __COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS National Park Service, Rocky Mountain Regional Office CITY. TOWN Denver„ STATEColorado DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED X—UNALTERED _RUINS __ALTERED _ MOVED DATE_ _ FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Obsidian Cliff Kiosk nomination'is a portion of the multiple resource nomination^ for Yellowstone National Park, The. -

Yellowstone Today

YELLOWSTONE Today National Park Service Spring 2009 Official Newspaper of Yellowstone National Park U.S. Department of the Interior Throughout the Park TRAFFIC DELAYS & ROAD CLOSURES See back page & below NPS/Peaco The Albright Visitor Center at Mammoth Hot Springs, above, is part of historic Fort Yellowstone. In This Issue This and other stone buildings at the fort were built 100 years ago. MAP & ROAD INFORMATION .Back Cover Fort Yellowstone dates from the time the U.S. Army managed the park, 1886–1918. You can enjoy a self-guiding trail around the fort by following the exhibits that begin in front of the visitor center. Safety . .2 You can also purchase a guide that explains even more about this National Historic Landmark District. Plan Your Visit . .3 Highlights . .4 “Greening” Yellowstone . 5 Expect Delays as You Travel In the Park Camping, Fishing, Hiking . 6–7 See map on the back page. Symbols of Yellowstone . 8 Plan your day to minimize delays. Our rangers • If animals are nearby, stay safe—stay in your offer these tips: car and watch them through the windows. Spring Wildlife Gallery . .9 • Don’t wait until the last minute for a rest- • Enjoy this park newspaper! Friends of Yellowstone . 10 room stop—the next facility may be on the • Make notes about your trip so far—where other side of a 30-minute delay. Issues: Bison, Winter Use, Wolves . 11 you’ve been in Yellowstone, which features • Turn off your engine and listen to the wild and animals you’ve seen. Other NPS Sites Near Yellowstone . -

October 30, 2019 Local Announcements Last Reminder - Applications for the Gardiner Resort Area District Tax Funds Are Due Tomorrow, 10/31

October 30, 2019 Local Announcements Last reminder - Applications for the Gardiner Resort Area District tax funds are due tomorrow, 10/31. You MUST have at least one representative available at our November meeting to answer any questions we might have. Funds will be assigned in December. Thank you to everyone who has applied. We will see you 11/12 at 7pm upstairs at the Chamber of Commerce. Public Meeting Notice: The Gardiner Resort Area District will hold its regular monthly meeting on Tuesday, November 12th at 7:00 PM upstairs at the Chamber of Commerce. The public is welcome to attend. For further information go to www.gardinerresorttax.com. The Electric Peak Arts Council presents it’s first visual art event on Thursday, November 14 at 7:00pm at the Gardiner School Multipurpose Room. The artist Robert Stephenson, known on stage as Rohaun, will paint a large scale piece of art in conjunction with a musical performance by Maiah Wynne. Rohaun’s work explores the depths of the human experience to tell stories that often go unheard. Twenty-two year old multi-instrumentalist, indie-folk singer-songwriter Maiah Wynne has the kind of hauntingly beautiful voice that can cause a room full of people to fall still, silently taking in every word and note. Breast Cancer Awareness Raffle at the Town Station Conoco will be ending tomorrow! Last chance tickets! Drawing held on 11/1/19. Thank you to all who donated and good luck! Wade, Paula & the crew. Town Station Conoco remodel project has progressed to the point where we will be unable to sell gas for a few weeks. -

Jackson Hole Vacation Planner Vacation Hole Jackson Guide’S Guide Guide’S Globe Addition Guide Guide’S Guide’S Guide Guide’S

TTypefypefaceace “Skirt” “Skirt” lightlight w weighteight GlobeGlobe Addition Addition Book Spine Book Spine Guide’s Guide’s Guide’s Guide Guide’s Guide Guide Guide Guide’sGuide’s GuideGuide™™ Jackson Hole Vacation Planner Jackson Hole Vacation2016 Planner EDITION 2016 EDITION Typeface “Skirt” light weight Globe Addition Book Spine Guide’s Guide’s Guide Guide Guide’s Guide™ Jackson Hole Vacation Planner 2016 EDITION Welcome! Jackson Hole was recognized as an outdoor paradise by the native Americans that first explored the area thousands of years before the first white mountain men stumbled upon the valley. These lucky first inhabitants were here to hunt, fish, trap and explore the rugged terrain and enjoy the abundance of natural resources. As the early white explorers trapped, hunted and mapped the region, it didn’t take long before word got out and tourism in Jackson Hole was born. Urbanites from the eastern cities made their way to this remote corner of northwest Wyoming to enjoy the impressive vistas and bounty of fish and game in the name of sport. These travelers needed guides to the area and the first trappers stepped in to fill the niche. Over time dude ranches were built to house and feed the guests in addition to roads, trails and passes through the mountains. With time newer outdoor pursuits were being realized including rafting, climbing and skiing. Today Jackson Hole is home to two of the world’s most famous national parks, world class skiing, hiking, fishing, climbing, horseback riding, snowmobiling and wildlife viewing all in a place that has been carefully protected allowing guests today to enjoy the abundance experienced by the earliest explorers. -

Yellowstone Visitor Guide 2019

Yellowstone Visitor Guide 2019 Are you ready for your Yellowstone adventure? Place to stay Travel time Essentials Inside Hotels and campgrounds fill up Plan plenty of time to get to Top 5 sites to see: 2 Welcome quickly, both inside and around your destination. Yellowstone 1. Old Faithful Geyser 4 Camping the park. Make sure you have is worth pulling over for! 2. The Grand Canyon of the secured lodging before you make Plan a minimum of 40 minutes Yellowstone River 5 Activities other plans. If you do not, you to travel between junctions or 3. Yellowstone Lake 7 Suggested itineraries may have to drive several hours visitor service areas on the Grand 4. Mammoth Hot Springs away from the park to the nearest Loop Road. The speed limit in Terraces 8 Famously hot features available hotel or campsite. Yellowstone is 45 mph (73 kph) 5. Hayden or Lamar valleys 9 Wild lands and wildlife except where posted slower. 10 Area guides 15 Translations Area guides....pgs 10–14 Reservations.......pg 2 Road map.......pg 16 16 Yellowstone roads map Emergency Dial 911 Information line 307-344-7381 TTY 307-344-2386 Park entrance radio 1610 AM = Medical services Yellowstone is on 911 emergency service, including ambulances. Medical services are available year round at Mammoth Clinic (307- 344-7965), except some holidays. Services are also offered at Lake Clinic (307-242-7241) and at Old Faithful Clinic (307-545-7325) during the summer visitor season. Welcome to Yellowstone National Park Yellowstone is a special place, and very different from your home. -

Yellowstone National Park Family

Yellowstone National Park Family Trip Summary Yellowstone National Park is a paradise for family adventure. Our expert guides create a secure and rewarding environment full of challenge, accomplishment and fun, in the world’s first national park: Yellowstone. Combined with exceptional accommodations and classic dining, this is the ultimate family vacation. Hike into the Yellowstone’s backcountry, through the rainbow spray of a thundering waterfall and a shooting geyser. Raft a playful stretch of the beautiful Yellowstone River, perfect for beginners. Wind your way along a trail high into the Montana Rockies on horseback alongside a real-deal fourth generation cowboy. And when night falls, relax and recharge with a soak in soothing hot spring waters. Itinerary Day 1: West Yellowstone / Upper Geyser Basin / Old Faithful Meet in Bozeman and shuttle to the town of West Yellowstone, Montana where we will start our adventure with a thrilling ropes course adventure • After lunch, we'll make our way into the west entrance of Yellowstone • Upon arrival to the Upper Geyser Basin we'll hike in the back way, traversing through an area of bubbling hot springs to the main attraction, Old Faithful • After checking into our home for the night, walk to the historic Old Faithful Inn for dinner and a chance to watch Old Faithful erupt under the stars • Overnight Old Faithful Snow Lodge or Old Faithful Inn (L, D) Day 2: Upper Geyser Basin / Yellowstone Lake Begin the day with a ranger-guided hike through the Upper Geyser Basin to explore the many geysers -

Foundation Document Overview Yellowstone National Park Wyoming, Montana, Idaho

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Overview Yellowstone National Park Wyoming, Montana, Idaho Contact Information For more information about the Yellowstone National Park Foundation Document, contact: [email protected] or 307-344-7381 or write to: Superintendent, Yellowstone National Park, PO Box 168, Yellowstone National Park, WY 82190-0168 Park Description Yellowstone became the world’s first national park on March This vast landscape contains the headwaters of several major 1, 1872, set aside in recognition of its unique hydrothermal rivers. The Firehole and Gibbon rivers unite to form the Madison, features and for the benefit and enjoyment of the people. which, along with the Gallatin River, joins the Jefferson to With this landmark decision, the United States Congress create the Missouri River several miles north of the park. The created a path for future parks within this country and Yellowstone River is a major tributary of the Missouri, which around the world; Yellowstone still serves as a global then flows via the Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico. The Snake resource conservation and tourism model for public land River arises near the park’s south boundary and joins the management. Yellowstone is perhaps most well-known for its Columbia to flow into the Pacific. Yellowstone Lake is the largest hydrothermal features such as the iconic Old Faithful geyser. lake at high altitude in North America and the Lower Yellowstone The park encompasses 2.25 million acres, or 3,472 square Falls is the highest of more than 40 named waterfalls in the park. miles, of a landscape punctuated by steaming pools, bubbling mudpots, spewing geysers, and colorful volcanic soils. -

Landsat Evaluation of Trumpeter Swan Historical Nesting Sites In

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Online Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship 2014 Landsat Evaluation Of Trumpeter Swan Historical Nesting Sites In Yellowstone National Park Laura Elizabeth Cockrell Eastern Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://encompass.eku.edu/etd Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Ornithology Commons Recommended Citation Cockrell, Laura Elizabeth, "Landsat Evaluation Of Trumpeter Swan Historical Nesting Sites In Yellowstone National Park" (2014). Online Theses and Dissertations. 222. https://encompass.eku.edu/etd/222 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Online Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LANDSAT EVALUATION OF TRUMPETER SWAN HISTORICAL NESTING SITES IN YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK By Laura Elizabeth Cockrell Bachelor of Science California State University, Chico Chico, California 2007 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Eastern Kentucky University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE May, 2014 Copyright © Laura Elizabeth Cockrell, 2014 All rights reserved ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my family and friends for their unwavering support during this adventure. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This research was made possible through funding from the Yellowstone Park Foundation and the Society of Wetland Scientists Student Research Grant for support of field work, and by a Graduate Assistantship and Research Assistantship from the Department of Biological Sciences at Eastern Kentucky University. Thank you to Dr. Bob Frederick for his insight and persistence and for providing the GIS lab and to Dr. -

Yellowstone Wolf Project: Annual Report, 2009

YELLOWSTONE WOLFPROJECT ANNUAL REPORT 2009 Yellowstone Wolf Project Annual Report 2009 Douglas Smith, Daniel Stahler, Erin Albers, Richard McIntyre, Matthew Metz, Kira Cassidy, Joshua Irving, Rebecca Raymond, Hilary Zaranek, Colby Anton, Nate Bowersock National Park Service Yellowstone Center for Resources Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming YCR-2010-06 Suggested citation: Smith, D.W., D.R. Stahler, E. Albers, R. McIntyre, M. Metz, K. Cassidy, J. Irving, R. Raymond, H. Zaranek, C. Anton, N. Bowersock. 2010. Yellowstone Wolf Project: Annual Report, 2009. National Park Ser- vice, Yellowstone Center for Resources, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, YCR-2010-06. Wolf logo on cover and title page: Original illustration of wolf pup #47, born to #27, of the Nez Perce pack in 1996, by Melissa Saunders. Treatment and design by Renée Evanoff. All photos not otherwise marked are NPS photos. ii TABLE OF CON T EN T S Background .............................................................iv Wolf –Prey Relationships ......................................11 2009 Summary .........................................................v Composition of Wolf Kills ...................................11 Territory Map ..........................................................vi Winter Studies.....................................................12 The Yellowstone Wolf Population .............................1 Summer Predation ...............................................13 Population and Territory Status .............................1 Population Genetics ............................................14 -

2017 Experience Planner

2017 Experience Planner A Guide to Lodging, Camping, Dining, Shopping, Tours, and Activities in Yellowstone Don’t just see Yellowstone. Experience it. MAP LEGEND Contents LODGING Old Faithful Inn, Old Faithful Lodge Cabins, Old General Info 3 OF Must-Do Adventures 4 Faithful Snow Lodge & Cabins (pg 11-14) Visitor Centers & Park Programs 5 GV Grant Village Lodge (pg. 27-28) Visiting Yellowstone with Kids 6 Canyon Lodge & Cabins (pg 21-22) Tips for Summer Wildlife Viewing 9 CL 12 Awesome Day Hikes 19-20 LK Lake Yellowstone Hotel, Lake Lodge Cabins (pg 15-18) Photography Tips 23-24 M Mammoth Hot Springs Hotel & Cabins (pg 7-8) How to Travel Sustainably 29-30 Animals In The Park 33-34 RL Roosevelt Lodge (pg 25-26) Thermal Features 35-36 CAMPING Working in Yellowstone 43-44 (Xanterra-operated Campground) Partner Pages 45-46 Canyon, Madison, Bridge Bay, Winter Fishing Bridge RV Park, Grant Village (pg 31-32) Reasons to Visit in Winter 37-38 Winter Packages 39-40 DINING Winter Tours & Activities 41-42 Old Faithful Inn Dining Room, Bear Paw Deli, OF Obsidian Dining Room, Geyser Grill, Old Faithful Location Guides Lodge Cafeteria (pg 11-14) Grant Village Dining Room, Grant Village Lake House Mammoth Area 7-8 GV Old Faithful Area 11-14 (pg 27-28) Yellowstone Lake Area 15-18 Canyon Lodge Dining Room, Canyon Lodge Canyon Area 21-22 CL Roosevelt Area 25-26 Cafeteria, Canyon Lodge Deli (pg 21-22) Grant Village Area 27-28 Lake Yellowstone Hotel Dining Room, Lake Hotel LK Campground Info 31-32 Deli, Lake Lodge Cafeteria (pg 15-18) Mammoth Hot Springs Dining Room, Mammoth M Terrace Grill (pg 7-8) Roosevelt Lodge Dining Room. -

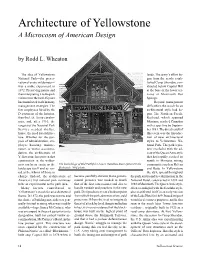

Architecture of Yellowstone a Microcosm of American Design by Rodd L

Architecture of Yellowstone A Microcosm of American Design by Rodd L. Wheaton The idea of Yellowstone lands. The army’s effort be- National Park—the preser- gan from the newly estab- vation of exotic wilderness— lished Camp Sheridan, con- was a noble experiment in structed below Capitol Hill 1872. Preserving nature and at the base of the lower ter- then interpreting it to the park races at Mammoth Hot visitors over the last 125 years Springs. has manifested itself in many Beyond management management strategies. The difficulties, the search for an few employees hired by the architectural style had be- Department of the Interior, gun. The Northern Pacific then the U.S. Army cavalry- Railroad, which spanned men, and, after 1916, the Montana, reached Cinnabar rangers of the National Park with a spur line by Septem- Service needed shelter; ber 1883. The direct result of hence, the need for architec- this event was the introduc- ture. Whether for the pur- tion of new architectural pose of administration, em- styles to Yellowstone Na- ployee housing, mainte- tional Park. The park’s pio- nance, or visitor accommo- neer era faded with the ad- dation, the architecture of vent of the Queen Anne style Yellowstone has proven that that had rapidly reached its construction in the wilder- zenith in Montana mining ness can be as exotic as the The burled logs of Old Faithful’s Lower Hamilton Store epitomize the communities such as Helena landscape itself and as var- Stick style. NPS photo. and Butte. In Yellowstone ied as the whims of those in the style spread throughout charge.