Motivation &Engagement of Boys

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Humble Beginnings to a Leader in Child and Family Care

® WINTER 2017 Boys Town, Yesterday and Today From Humble Beginnings to a Leader in Child and Family Care ecember 12, 1917, was a chilly day in Omaha, Nebraska. Passers-by hurried along the D downtown streets, their thoughts perhaps on Christmas, only two weeks away, and the preparations they still needed to make. Or, maybe they were wondering how the holidays would be different this year, with America now involved in the Great War being waged on the battlefields of Europe. In all the hustle and bustle, no one paid much attention to the tall, bespectacled priest who was shepherding several ragamuffin boys along the sidewalk. When the little group reached a somewhat run-down Victorian-style boardinghouse, the priest confidently strode to the front door, unlocked it and bade his young charges to enter. Once inside, he turned to the cluster of expectant faces and welcomed the boys Over a proud history spanning 100 years, Boys Town has provided life-changing love and care for America’s children! to their new home. There was no ribbon-cutting ceremony. Father Flanagan had borrowed $90 hard-pressed to provide enough food and No parade with marching bands. No from a businessman friend to rent the clothing for his boys. And as Christmas speech by the mayor. On that ordinary property. For at least a month, the boys approached, the prospects for a happy day, in that ordinary place, Father would have a roof over their heads. But holiday were bleak. By the morning of Flanagan’s Home for Boys (later to be there wasn’t much else. -

Bring Back Our Boys – Jared Feldshreiber

WEEKLY BRING BACK Candle-lighting/Shabbos ends Friday, June 27: 8:12/9:21 OUR BOYS Vol. III No. 18 (#67) June 26, 2014 • 28 Sivan 5774 Free Lakewood Rabbanim Visit Community Unites New York City Offi cials Queens On Behalf Of At Prayer Gathering For Stand In Solidarity With Beth Medrash Govoha Kidnapped Boys In Israel Israel After Kidnapping Of Three Jewish Teenagers SEE STORY ON P. 55 SEE PHOTOS ON 36/37; ARTICLE ON P. 52 SEE STORY ON P. 39 Shabbos Inbox Blue And White Op-Ed Politics And Ethics Hooked On Healing (D)Anger Tragedy Helplessness Situational To Give Management Brings Unity By Betsalel Steinhart Awareness Or Not To Give Is Derech Eretz By Eytan Kobre By Shmuel Sackett hat can we do in the By Caroline Schumsky face of helplessness? By Abe Fuchs o goes the well-known hy do we do this to W This question is ooo… You want to give joke: ourselves? Why do being asked so many times, somehow, some way. S Husband to Wife: Wwe fi ght like dogs and over the last few days, as our and another person were SYou want to dedicate When I get mad at you, you cats until tragedy strikes? Why darkest fears take shape, as waiting on line at a bank the or allocate, but not so sure never fi ght back. How do you does it take the kidnapping of three boys sit who-knows- Iother day when there was how or where or how often? control your anger? three precious boys to bring us where, as three families lie only one teller available. -

Newsletter 2017 - October Volume 23 No 7 2 November 2017

Palmerston North Boys’ High School @PalmyBoys PalmerstonPalmerston North Boys’ North High School Boys’ – International High School College House PNBHS stratus.pnbhs.school. PNBHS Old Boys Association PNBHS Newsletter 2017 - October Volume 23 No 7 2 November 2017 Old Boy Brendon Hartley gets first ride in Formula One Old Boy Hadleigh Parkes gets call-up for Wales (above left) Mountain bikers Hayden Storrier, Caleb Bottcher and Adam Francis (page 9); Fred Hollows Day - Patrick Takurua and Hamzah Arafeh show what it’s like to have cataracts; Xavier Bowe, Chase Maniapoto and Mason Gerrard gained their level 1 in Mau Rākau, a Maori martial art Phoenix win Shand Shield Choral Senior Monrad Cup - Long Ball. Spot the ball! (left to right) ICAS English - High Distinction winners; ICAS Distinction winners Year 10 Specials vs 1992 1st XI Cricket reunion team Palmerston North Boys’ High School Major Sponsor Partners McVerry Crawford pageThe school1 acknowledges the above businesses, who through their significant sponsorship arrangements, assist us in developing young men of outstanding character. We appreciate their support and encourage you to also support them in return From the Rector Mr David Bovey Dear Parents The end of another busy year is nigh, and this last newsletter for 2017 celebrates another impressive range of achievement and involvement from the young men of the school. A number of the young men who feature in this edition will be leaving us in a few short weeks and heading out into the world. While the achievements of the young men of the school, not just those who feature in this newsletter, but all of those who have done well throughout the year, are impressive, they do not happen by accident. -

A Cultural Analysis of the Russo-Soviet Anekdot

A CULTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE RUSSO-SOVIET ANEKDOT by Seth Benedict Graham BA, University of Texas, 1990 MA, University of Texas, 1994 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2003 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Seth Benedict Graham It was defended on September 8, 2003 and approved by Helena Goscilo Mark Lipovetsky Colin MacCabe Vladimir Padunov Nancy Condee Dissertation Director ii Copyright by Seth Graham 2003 iii A CULTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE RUSSO-SOVIET ANEKDOT Seth Benedict Graham, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2003 This is a study of the cultural significance and generic specificity of the Russo-Soviet joke (in Russian, anekdot [pl. anekdoty]). My work departs from previous analyses by locating the genre’s quintessence not in its formal properties, thematic taxonomy, or structural evolution, but in the essential links and productive contradictions between the anekdot and other texts and genres of Russo-Soviet culture. The anekdot’s defining intertextuality is prominent across a broad range of cycles, including those based on popular film and television narratives, political anekdoty, and other cycles that draw on more abstract discursive material. Central to my analysis is the genre’s capacity for reflexivity in various senses, including generic self-reference (anekdoty about anekdoty), ethnic self-reference (anekdoty about Russians and Russian-ness), and critical reference to the nature and practice of verbal signification in more or less implicit ways. The analytical and theoretical emphasis of the dissertation is on the years 1961—86, incorporating the Stagnation period plus additional years that are significant in the genre’s history. -

A Fun-Filled Year's End P

101 N. Warson Road Saint Louis, MO 63124 Non-Profit Organization Address Service Requested United States Postage PAID Saint Louis, Missouri PERMIT NO. 230 THE MAGAZINE VOLUME 28 NO. 3 | FALL 2018 THEN − & − NOW A Fun-Filled Year's End p . 2 0 A May Tradition: May Day has been a tradition since the earliest moments at Mary Institute and continues as a staple of the MICDS experience. Here's a look at May Day in 1931 and 2018. 16277_MICDSMag_CV.indd 1 8/15/18 10:00 AM ABOUT MICDS MAGAZINE MICDS Magazine has been in print since 1993. It is published three times per year. Unless otherwise noted, articles may be reprinted with credit to MICDS. EDITOR Jill Clark DESIGN Almanac HEAD OF SCHOOL Lisa L. Lyle DIRECTOR OF MARKETING & COMMUNICATIONS Monica Shripka MULTIMEDIA SPECIALIST Glennon Williams CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Crystal D'Angelo Wes Jenkins Lisa L. Lyle OUR MISSION Monica Shripka Britt Vogel More than ever, our nation needs responsible CLASS NOTES COPY EDITORS men and women who can meet the challenges Anne Stupp McAlpin ’64 Libby Hall McDonnell ’58 of this world with confidence and embrace all its Peggy Dubinsky Price ’65 Cliff Saxton ’64 people with compassion. The next generation must include those who think critically and ADDRESS CHANGE Office of Alumni and Development resolve to stand for what is good and right. MICDS, 101 N. Warson Rd. St. Louis, MO 63124 Our School cherishes academic rigor, encourages CORRESPONDENCE and praises meaningful individual achievement Office of Communications MICDS, 101 N. Warson Rd. and fosters virtue. Our independent education St. -

'Lose in Vietnam, Bring Our Boys Home'

Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons Faculty Publications 2004 ‘Lose in Vietnam, Bring Our Boys Home’ Robert N. Strassfeld Case Western Reserve University - School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Strassfeld, Robert N., "‘Lose in Vietnam, Bring Our Boys Home’" (2004). Faculty Publications. 267. https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/faculty_publications/267 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. "LOSE IN VIETNAM, BRING THE BOYS HOME" ROBERTN. STRASSFELD. This Article examines the contest over dissent and loyalty during the Vietnam War. The Johnson and Nixon Administrations used an array of weapons to discourage or silence antiwar opposition. These included crinLinal prosecutions for "disloyal speech," a tool that they used with less frequency than s01ne other administrations in times of war; prosecutions for other "crimes" that served as pretext for prosecuting disloyal speech; infiltration and harassment; and an attempt to characterize their critics as disloyal. The antiwar movement, in turn, responded to allegations that dissent equaled disloyalty by offering an alternative vision of loyalty and patriotism. In so doing, they recast notions of allegiance, betrayal, support of the troops, and our obligations in the face of conflicting loyalties. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................... 1892 I. THE USES OF LOYALTY IN THE VIETNAM WAR ERA ........... 1894 A. The Model of Legal Repression: The World War I Experience ........................................................................... -

A War-Modified Course of Study for the Public Schools of Colorado

c . / —I « 4 COLORADO STATE PUBLICATIONS LIBRARY ED2.2/W19/1918 v.3 local /A war-modified course of study for the ODIFIED 3 1799 00027 3466 OF STUDY HE PUBLS&4€*iOOLS OF COLORADO ID BY E DEPARTMENT'^W PUBLIC INSTRUCTION MARY C. C. BRADFORD. Superintendent 1918 VOLUME III E WORLD OF NATURE AND OF MAN lid have tess opportunity for \use of the war" —Woodrow Wilson IPARED BY C. BRADFORD lting Educators 1918 lENVER TATI Pm\HTi /^.uLiiur UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO LIBRARY CIRCULATING BOOK \l , J ^ Accession No. r O 3L O Form 273. 8-22-lOM ^^^^^^ T^^i,s 7 J " A WAR-MODIFIED COURSE OF STUDY ^ FOR THE PUBLIC SCHOOLS OF COLORADO " ISSUED B\^^ THE DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION MARY C. C. BRADFORD, Superintendent 1918 VOLUME III THE WORLD OF NATURE AND OF MAN **J^o child should have less opportunity for education because of the war*' —Woodrow Wilson PREPARED BY MARY C. C. BRADFORD AND CO-OpERATING EDUCATORS 1918 DENVER EAMES BROS.. STATE PRINTERS NOTICE Teachers of Colorado: This volume is public property and is not to be removed from the district when you leave. The State of Colorado provides these books, paying for them from the State School Fund. They are ordered by your County Superintendent for use by any teacher who may be in charge of the school where you are now teaching. "War service demands conservation of books and ail other school material. Therefore, as a matter of honor and an obliga- tion of patriotism, please regard this book as public property, not for personal ownership. -

The Baltimore County Board of School Commissioners

Proceedings Baltimore City Public School Board Meeting 1 THE BALTIMORE COUNTY BOARD OF SCHOOL 2 COMMISSIONERS 3 BALTIMORE COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS 4 5 6 PUBLIC BOARD MEETING 7 BALTIMORE, MARYLAND 8 9 10 MAY 7, 2019 11 5:00 P.M. 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 CRC Salomon, Inc. www.crcsalomon.com - [email protected] Page: 1 (1) Office (410) 821-4888 2201 Old Court Road, Baltimore, MD 21208 Facsimile (410) 821-4889 Proceedings Baltimore City Public School Board Meeting Page 2 Page 4 1 MEMBERS: 1 Anna Gaffold. 57 2 2 Jessie Lehson . 61 3 Kathleen S. Causey, Board Chair 3 Public Comment on Proposed Changes to 4 Julie C. Henn, Vice Chair 4 Policies. 65 5 Roger B. Hayden 5 Superintendent's Report . 78 6 Moalie S. Jose 6 Chair's Report. 88 7 Russell T. Kuehn 7 Student Board's Report. 94 8 Lisa A. Mack 8 Unfinished Business . 97 9 Rodney R. McMillion 9 New Business. 99 10 John H. Offerman 10 Considerations of Policy. 97 11 Cheryl E. Pasteur 11 Personnel Matters . 99 12 Lily P. Rowe 12 Administrative Appointments . 100 13 Makeda Scott 13 Actions Taken in Closed Session . 103 14 Haleemat Adekoya, Student Member 14 Northeast Area Middle School Boundary . 105 15 15 Contract Awards . 146 16 16 Curricula . 152 17 17 West Towson Elementary. 157 18 18 Dogwood and Johnnycake Release Studies. 159 19 19 Board Member Comments . 180 20 20 Upcoming Meetings . 196 21 21 Close of Meeting. 196 Page 3 Page 5 1 I N D E X 1 P R O C E E D I N G S 2 Call to Order . -

Smart Boys, Bad Grades

Smart Boys, Bad Grades Gender Inequality and STEM in Education By Julie Coates and William A. Draves © 2015 by Julie Coates and William A. Draves. All rights reserved. No por- tion of this book, with the exception of “Chapter 11 For Parents of Boys”, may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written per- mission from the authors, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews and articles. “Chapter 11 For Parents of Boys” may be reproduced as long as the following information is included, “From Smart Boys, Bad Grades: Gender Inequality and Stem in Education, by Julie Coates and William A. Draves.” Published by LERN Books, a division of the Learning Resources Network (LERN), P.O. Box 9, River Falls, Wisconsin 54022, U.S.A. Phone: 800-678-5376; email [email protected]; URL: www.lern.org Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Coates, Julie, 1946- Smart Boys ISBN 978-1-57722-045-9 Manufactured in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 Dedication To our smart boys, to your smart boys, to smart boys everywhere. Thank you for creating the 21st century Cover Four smart boys. From left to right – Landon, Graham, Will and Ray. Photo taken in 2013 when they were around age 27. They are smart, successful at work, motivated and hard working. Yet our edu- cational institutions at the time of this writing graduated only 1 of the 4 with a four year college degree. Acknowledgments We wish to thank firstly, the Board of Directors of the Learning Resources Network (LERN) for their support of gender equality in education. -

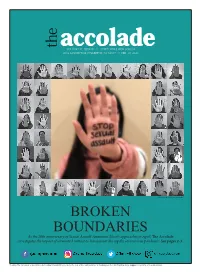

Broken Boundaries

the accolade VOLUME LXI, ISSUE III // SUNNY HILLS HIGH SCHOOL 1801 LANCER WAY, FULLERTON, CA 92833 // FEB. 19, 2021 HANNAH KIM | theaccolade* BROKEN BOUNDARIES As the 20th anniversary of Sexual Assault Awareness Month approaches in April, !e Accolade investigates the impact of unwanted contact or harassment during the coronavirus pandemic. See pages 2-3. *Led by The Accolade’s special sections editor Hannah Kim (center), the rest of the staff joins her in holding out their left hand to show support for victims of sexual assault. 2 February 19, 2021 BROKEN BOUNDARIES the accolade Treating controversial Media issues in ‘fair, ethical manner’ overselling If you have any questions, comments or concerns about the content of this ar- illicit ticle, we strongly encourage you to con- tact us at [email protected]. If you wish to report any cases of sexual misconduct, please talk to a trusted adult. content This is a safe school. As editor-in-chief, I’ve had the oppor- ERIN LEE | theaccolade tunity to speak with our administration MARKETING INAPPROPRIATE BEHAVIOR: An artist's rendering of the South Korean comic book cover, Painter frequently, and as a Sunny Hills student, of the Night. The series, which features an artist forced to illustrate erotic scenes, has recently grown in popularity. I can attest that sexual misconduct is NOT a rampant problem on campus. If you have any questions, comments For the full story, go to complexity, the fact that the protagonist is Nevertheless, it’s or concerns about the content of this arti- shhsaccolade.com/category/ encaged in a sexually violent prison sky- still a serious issue cle, we strongly encourage you to contact special-sections rocketed this manhwa to the No. -

The Christ the King CYO Newsletter

December 22, 2017 The Christ the King The CYO Newsletter Pastor: Father Joseph Davanzo Executive Director: John Newman Assistant Director: Dennis Briordy FAST BREAK tter Executive Assistant: Michelle Mardiney Fast th FAST BREAK is a monthly newsletter published by the evaluations held on January 6 beginning at 930am CTK CYO in order to bring everyone the latest news, at the CTK Gym. Participants will be notified of updates, and accomplishments of our boys and girls their specific reporting time via email. CYO Basketball Program teams and girls CYO Volleyball Program teams. CTK CYO has now become a year round program ready to bring basketball to anyone interested in playing throughout the year. CTK now offers Spring, Summer, Fall and Winter basketball programs for both girls and boys as well as individual personalized instruction. Volleyball for girls grades 6 and 7 is also now a part of the CTK CYO Program. Go to the CTK CYO website ctkcyo.net for further information Boys Divisons and check the ANNOUNCEMENT section of the Grades 5 thru 8- The boys winter season has begun and NEWSLETTER for updates. the teams are off to a terrific start. In the 5th grade division Brian McConaghy’s team is 2-1 after defeating a tough St. Joseph of Hewlett on 12/16 by the score of 27- 20. Coach Rosenoff’s 6th grade team is once again WHAT’S HAPPENING making an early statement as evidenced by their 3-0 record. Coach Newfield’s 7th grade team and Coach Spinelli’s 8th grade team are both showing early signs of making a serious title run as both teams are 3-1. -

Volume 81, Issue 7

June 12, 2018 The MOUNTAINEER Page 1 THE MOUNTAINEER Volume 81, Issue 7 The official newspaper of The American Legion Mountaineer Boys State hp://f.wvboysstate.org Boys State Legislature working in the Senate and hp://t.wvvboysstate.org House Chambers at the Capitol #ALMBS A Week That Shapes A Lifetime! http://wvboysstate.org June 12, 2018 The MOUNTAINEER Page 2 Farewell Mountaineer Boys State! By: Alex Joshua Mullins Today marks the last day for the citizens of Mountaineer Boys State. A somber and sad time for some and with that feeling all of the citizens will leave Jackson’s Mill with the knowledge of government and friendships that will last a life time and beyond. My experience here at Mountaineer Boys State has been one I will take back to Boone County with me and tell my peers and family about. Especially, the opportunities and responsibilities they bestowed upon me. When I first came to this camp on Sunday evening I didn't know what to expect. I was apart of a strong population with four hundred boys from all counties of this state. I was also very nervous. I have never been to a place where I didn't know a lot of people and that I needed to adapt to those changes. Although, throughout the week I met people around the grounds with many and I'm sure I will want to keep in contact with them. I befriended a few in my cabin that shares the same views and interests as me. Which was good for me because I could finally tell some of my political jokes and they would laugh! The best part of my time here would have to be my job as a reporter for the Mountaineer Boys State paper.