Religious Weaknesses in the Spirit of a Culture; and Attribute Our Difficulties Solely to the One Or to the Other

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Exemplar Texts for Grades

COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS FOR English Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects _____ Appendix B: Text Exemplars and Sample Performance Tasks OREGON COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS FOR English Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects Exemplars of Reading Text Complexity, Quality, and Range & Sample Performance Tasks Related to Core Standards Selecting Text Exemplars The following text samples primarily serve to exemplify the level of complexity and quality that the Standards require all students in a given grade band to engage with. Additionally, they are suggestive of the breadth of texts that students should encounter in the text types required by the Standards. The choices should serve as useful guideposts in helping educators select texts of similar complexity, quality, and range for their own classrooms. They expressly do not represent a partial or complete reading list. The process of text selection was guided by the following criteria: Complexity. Appendix A describes in detail a three-part model of measuring text complexity based on qualitative and quantitative indices of inherent text difficulty balanced with educators’ professional judgment in matching readers and texts in light of particular tasks. In selecting texts to serve as exemplars, the work group began by soliciting contributions from teachers, educational leaders, and researchers who have experience working with students in the grades for which the texts have been selected. These contributors were asked to recommend texts that they or their colleagues have used successfully with students in a given grade band. The work group made final selections based in part on whether qualitative and quantitative measures indicated that the recommended texts were of sufficient complexity for the grade band. -

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie 2014 T 06

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie Reihe T Musiktonträgerverzeichnis Monatliches Verzeichnis Jahrgang: 2014 T 06 Stand: 18. Juni 2014 Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (Leipzig, Frankfurt am Main) 2014 ISSN 1613-8945 urn:nbn:de:101-ReiheT06_2014-7 2 Hinweise Die Deutsche Nationalbibliografie erfasst eingesandte Pflichtexemplare in Deutschland veröffentlichter Medienwerke, aber auch im Ausland veröffentlichte deutschsprachige Medienwerke, Übersetzungen deutschsprachiger Medienwerke in andere Sprachen und fremdsprachige Medienwerke über Deutschland im Original. Grundlage für die Anzeige ist das Gesetz über die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (DNBG) vom 22. Juni 2006 (BGBl. I, S. 1338). Monografien und Periodika (Zeitschriften, zeitschriftenartige Reihen und Loseblattausgaben) werden in ihren unterschiedlichen Erscheinungsformen (z.B. Papierausgabe, Mikroform, Diaserie, AV-Medium, elektronische Offline-Publikationen, Arbeitstransparentsammlung oder Tonträger) angezeigt. Alle verzeichneten Titel enthalten einen Link zur Anzeige im Portalkatalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek und alle vorhandenen URLs z.B. von Inhaltsverzeichnissen sind als Link hinterlegt. Die Titelanzeigen der Musiktonträger in Reihe T sind, wie sche Katalogisierung von Ausgaben musikalischer Wer- auf der Sachgruppenübersicht angegeben, entsprechend ke (RAK-Musik)“ unter Einbeziehung der „International der Dewey-Dezimalklassifikation (DDC) gegliedert, wo- Standard Bibliographic Description for Printed Music – bei tiefere Ebenen mit bis zu sechs Stellen berücksichtigt ISBD (PM)“ zugrunde. -

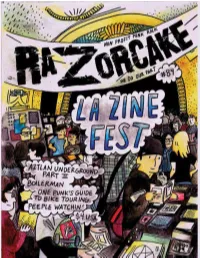

Razorcake Issue #84 As A

RIP THIS PAGE OUT WHO WE ARE... Razorcake exists because of you. Whether you contributed If you wish to donate through the mail, any content that was printed in this issue, placed an ad, or are a reader: without your involvement, this magazine would not exist. We are a please rip this page out and send it to: community that defi es geographical boundaries or easy answers. Much Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. of what you will fi nd here is open to interpretation, and that’s how we PO Box 42129 like it. Los Angeles, CA 90042 In mainstream culture the bottom line is profi t. In DIY punk the NAME: bottom line is a personal decision. We operate in an economy of favors amongst ethical, life-long enthusiasts. And we’re fucking serious about it. Profi tless and proud. ADDRESS: Th ere’s nothing more laughable than the general public’s perception of punk. Endlessly misrepresented and misunderstood. Exploited and patronized. Let the squares worry about “fi tting in.” We know who we are. Within these pages you’ll fi nd unwavering beliefs rooted in a EMAIL: culture that values growth and exploration over tired predictability. Th ere is a rumbling dissonance reverberating within the inner DONATION walls of our collective skull. Th ank you for contributing to it. AMOUNT: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc., a California non-profit corporation, is registered as a charitable organization with the State of California’s COMPUTER STUFF: Secretary of State, and has been granted official tax exempt status (section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) from the United razorcake.org/donate States IRS. -

RUSH ... Albums & Lyrics

Finding My Way – RUSH track 1 – 5:06 You’ve done me no right, but you’ve done me some wrong. Yeah, oh yeah! Left me lonely each night Ooh, said I, while I sing my sad song. I’m comin’ out to get you. Ooh, sit down. Look out! I’m comin’. I’m comin’ out to find you. Whoa, whoa. Ooh, yeah. Ooh yeah. Look out! I’m comin’. Findin’ my way! Whoa, yeah. I’ve been gone so long I’m runnin’, I’ve lost count of the years. findin’ my way back home. Well, I sang some sad songs, I’m comin’. oh yes, and cried some bad tears. Ooh, babe, I said I’m runnin’. Whoa, babe, I said I’m comin’ Look out! I’m comin’. to get you, mama. Whoa, whoa. Said I’m runnin’. Look out! I’m comin’. Whoa, yeah. Ooh, babe, I said I’m comin’ for you, babe. I’m runnin’, I said I’m runnin’. finding my way back home. Ooh yes, babe, I said I’m comin’ Oh yeah! to get you, babe. I said I’m comin’. Yeah, oh yeah! Ooh, yeah. Ooh, said I, I’m findin’, I’m comin’ back to look for you. I’m findin’ my way back home. Ooh, sit down. Well, I’ve had it for now, I’m goin’ by the back door. livin’ on the road. Ooh, yeah. Ooh yeah. Ooh, yeah. Findin’ my way! Ooh, yeah. Findin’ my way! I Need Some Love – RUSH track 2 – 2:19 I’m runnin’ here, I’m runnin’ there. -

The Book of 1 Peter

The Book of 1 Peter Introduction (1:1) Doctrine: Remember Our Great Salvation (1:2 - 2:10) The Certainty of Our Salvation (1:2 - 1:12) Elect According to the Foreknowledge of God (1:2) Preserved – Proven – Predicted (1:2 – 12) Predicted By the Prophets (1:10-12) The Calling with Our Salvation (1:13 - 2:3) The Chosen of Salvation (2:4 - 10) Duty: Remember Our Example Before Men (2:11 - 4:6) The Surrendered Life - The Witness to the World (2:9-12) Honorable Living Before Unbelievers (2:11 - 3:7) Submission of the Flesh - Principles of Fasting (2:11) Study - The Principles of Fasting (2:11) Link to Scriptures on Fasting Link to Dr. Bill Bright's Guide to Fasting and Prayer Submission to the Government (2:11-17) Submission to Masters (2:18 - 25) Submission in the Family (3:1- 7) Wives (3:1-6) Husbands (3:7) Honorable Living Before Believers (3:8 - 12) Submission to One Another (3:8 - 12) Honorable Living in the Midst of Suffering (3:13 - 4:6) The Principle of Suffering for Righteousness (3:13 - 17) The Perfection of Suffering for Righteousness (3:18- 22) The Purpose of Suffering for Righteousness (4:1 - 6) Declaration: Remember Our Lord Will Return (4:7 - 5:14) The Responsibility of Christian Living (4:7 - 11) The Rewards of Christian Suffering (4:12 - 19) The Requirements for Christian Leadership (5:1 - 4) The Realization of Christian Victory (5:5 - 14) Introduction (1:1) (1 Peter 1:1 NKJV) Peter, an apostle of Jesus Christ, To the pilgrims of the Dispersion in Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia, and Bithynia, Peter’s Life Written by Peter / Credentials Questions Written by Peter. -

The Challenge of Facts, and Other Essays

Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2007 witii funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation littp://www.arcliive.org/details/cliallengeoffactsOOsumniala WILLIAM GRAHAM SUMNER (1895) THE CHALLENGE OF FACTS AND OTHER ESSAYS THE CHALLENGE OF FACTS AND OTHER ESSAYS BY WILLIAM GRAHAM SUMNER EDITED BY ALBERT GALLOWAY KELLER NEW HAVEN: YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON: HUMPHREY MILFORD OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS MDCCCCXIV COPYRIGHT, 1914 BY YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS Copyright, 1886, by The Forum Copyright, 1886, 1887, 1890, 1891, 1902, by The Independent G)pyright. 1887, 1889, by D. Appleton & Company Copyright, 1901, by The Macmillan Company Copyright, 1904, by P. F. Collier & Son, Inc. Copyright, 1905, by Longmans, Green & Company Copyright, 1907, by The Univeraty of Chicago PreM riBBT PUBLISBEO, OCTOBER, 1914 SECOND PBIMTINO, OCTOBEB, 1916 " PREFATORY NOTE All rights on the essays in this work are reserved by the holders of the copyright. The PubHshers named in the subjoined Kst are the proprietors, either in their own right, or as agents for the author of the Essays of which the titles are given below, and of which the ownership is thus specifically noted. The Yale University Press makes grateful acknowledgment to the Publishers whose names appear below for their courteous permission to include in the present work the Essays of which they were the original publishers. Yale University Press The New Haven Palladium: "For President?" The Providence Evening Press: "Democracy and Responsible Government." The Chicago Tribune: "Republican Government." The Forum: "Indus- trial War." The Independent: "The Demand for Men," "The Sig- nificance of the Demand for Men," "What the 'Social Question' Is," "What Emancipates," "Power and Progress," "Consequences of Increased Social Power," "What is the 'Proletariat?'" "Who Win by Progress?" "Federal Legislation on Railroads," "Legisla- tion by Clamor," "The Shifting of Responsibility," "The State as an 'Ethical Person,'" "The New Social Issue," "Speculative Legis- lation," "The Concentration of Wealth: Its Economic Justification." Messrs. -

Baltim Re 2012

BALTIM RE 2012 72nd Annual Meeting Sheraton Baltimore City Center Hotel March 27-31, 2012 Sheraton Baltimore City Center Hotel Map Contents Welcome from the Program Chair ................................................................................................ iii SfAA 2012 Program Committee .....................................................................................................v Offcers of the Society for Applied Anthropology, Board of Directors, and Editors ............... vii Special Thanks and Co-Sponsors ................................................................................................ vii Past Presidents and Annual Meeting Sites ......................................................................................x General Information How to Use This Program .................................................................................................1 A Note About Abstracts .....................................................................................................1 Registration .......................................................................................................................1 Book Exhibit .....................................................................................................................1 Messages and Information ................................................................................................1 Plenary Sessions ................................................................................................................1 Social -

Proquest Dissertations

From freedom to slavery: Robert Montgomery Bird and the natural law tradition Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Buffington, Nancy Jane Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 09/10/2021 18:50:02 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/282827 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. -

Appendix B: Text Exemplars and Sample Performance Tasks

common core state STANDARDs FOR english Language arts & Literacy in History/social studies, science, and technical subjects appendix B: text exemplars and sample Performance tasks Common Core State StandardS for engliSh language artS & literaCy in hiStory/SoCial StudieS, SCienCe, and teChniCal SubjeCtS exemplars of reading text complexity, Quality, and range & sample Performance tasks related to core standards Selecting Text Exemplars The following text samples primarily serve to exemplify the level of complexity and quality that the Standards require all students in a given grade band to engage with. Additionally, they are suggestive of the breadth of texts that stu- dents should encounter in the text types required by the Standards. The choices should serve as useful guideposts in helping educators select texts of similar complexity, quality, and range for their own classrooms. They expressly do not represent a partial or complete reading list. The process of text selection was guided by the following criteria: • Complexity. Appendix A describes in detail a three-part model of measuring text complexity based on quali- tative and quantitative indices of inherent text difficulty balanced with educators’ professional judgment in matching readers and texts in light of particular tasks. In selecting texts to serve as exemplars, the work group began by soliciting contributions from teachers, educational leaders, and researchers who have experience working with students in the grades for which the texts have been selected. These contributors were asked to recommend texts that they or their colleagues have used successfully with students in a given grade band. The work group made final selections based in part on whether qualitative and quantitative measures indicated that the recommended texts were of sufficient complexity for the grade band. -

Unlocking the Paradox of Christian Metal Music

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2013 Unlocking the Paradox of Christian Metal Music Eric S. Strother University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Strother, Eric S., "Unlocking the Paradox of Christian Metal Music" (2013). Theses and Dissertations-- Music. 9. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/9 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies. I retain all other ownership rights to the copyright of my work. -

Helvet-Black Metal Journal 1.Pdf

HELVETE A JOURNAL OF BLACK METAL THEORY Issue 1: Incipit Winter 2013 HELVETE A JOURNAL OF BLACK METAL THEORY Issue 1: Incipit Winter 2013 ISSN: 2326-683X Helvete: A Journal of Black Metal Theory is also available in open-access forM: http://helvetejournal.org EDITORS Amelia IshMael Zareen Price Aspasia Stephanou Ben Woodard LAYOUT EDITOR Andrew DotY http://creativecomMons.org/licenses/bY-nc-nd/3.0/ Published bY punctuM books Brooklyn, New York http://punctuMbooks.com ISBN-13: 978-0615758282 ISBN-10: 0615758282 1 DILATION: EDITOR’S PREFACE Zareen Price 5 OPEN A VEIN: SUICIDAL BLACK METAL AND ENLIGHTENMENT Janet Silk ASDF 21 AT THE EDGE OF THE SMOKING POOL OF DEATH: WOLVES IN THE THRONE ROOM Timothy Morton 29 BAPTISM OR DEATH: BLACK METAL IN CONTEMPORARY ART, BIRTH OF A NEW AESTHETIC CATEGORY Elodie Lesourd THE NIGHT IS NO LONGER DEAD; IT HAS A LIFE OF ITS OWN Amelia Ishmael FROSTBITE ON MY FEET: REPRESENTATIONS OF WALKING 45 IN BLACK METAL VISUAL CULTURE David Prescott-Steed BLACK METAL MACHINE: THEORIZING INDUSTRIAL BLACK 69 METAL Daniel Lukes THIS IS ARMAGEDDON: THE DAWN MOTIF AND BLACK 95 METAL’S ANTI-CHRISTIAN PROJECT Joel Cotterell DILATION EDITOR’S PREFACE Zareen Price The open door and gaping shadowy halls stand wide in cold splendor of marble and stone / And from pulpits appear faces that stare, cruel mockeries of the closest in life now gone1 This is an opening. These are the first words, the opening text, of a project I conceived late in the winter of 2011. Melancology, the second iteration of the Black Metal TheorY SYmposium, had recentlY oozed through London, and the internet-lurking underground’s immune reaction to the intermingling of Black Metal and theorY was seeminglY at its most captious.