Systems Reboot: Sanitation Sector Change in Maputo and Lusaka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mozambique Zambia South Africa Zimbabwe Tanzania

UNITED NATIONS MOZAMBIQUE Geospatial 30°E 35°E 40°E L a k UNITED REPUBLIC OF 10°S e 10°S Chinsali M a l a w TANZANIA Palma i Mocimboa da Praia R ovuma Mueda ^! Lua Mecula pu la ZAMBIA L a Quissanga k e NIASSA N Metangula y CABO DELGADO a Chiconono DEM. REP. OF s a Ancuabe Pemba THE CONGO Lichinga Montepuez Marrupa Chipata MALAWI Maúa Lilongwe Namuno Namapa a ^! gw n Mandimba Memba a io u Vila úr L L Mecubúri Nacala Kabwe Gamito Cuamba Vila Ribáué MecontaMonapo Mossuril Fingoè FurancungoCoutinho ^! Nampula 15°S Vila ^! 15°S Lago de NAMPULA TETE Junqueiro ^! Lusaka ZumboCahora Bassa Murrupula Mogincual K Nametil o afu ezi Namarrói Erego e b Mágoè Tete GiléL am i Z Moatize Milange g Angoche Lugela o Z n l a h m a bez e i ZAMBEZIA Vila n azoe Changara da Moma n M a Lake Chemba Morrumbala Maganja Bindura Guro h Kariba Pebane C Namacurra e Chinhoyi Harare Vila Quelimane u ^! Fontes iq Marondera Mopeia Marromeu b am Inhaminga Velha oz P M úngu Chinde Be ni n è SOFALA t of ManicaChimoio o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o gh ZIMBABWE o Bi Mutare Sussundenga Dondo Gweru Masvingo Beira I NDI A N Bulawayo Chibabava 20°S 20°S Espungabera Nova OCE A N Mambone Gwanda MANICA e Sav Inhassôro Vilanculos Chicualacuala Mabote Mapai INHAMBANE Lim Massinga p o p GAZA o Morrumbene Homoíne Massingir Panda ^! National capital SOUTH Inhambane Administrative capital Polokwane Guijá Inharrime Town, village o Chibuto Major airport Magude MaciaManjacazeQuissico International boundary AFRICA Administrative boundary MAPUTO Xai-Xai 25°S Nelspruit Main road 25°S Moamba Manhiça Railway Pretoria MatolaMaputo ^! ^! 0 100 200km Mbabane^!Namaacha Boane 0 50 100mi !\ Bela Johannesburg Lobamba Vista ESWATINI Map No. -

Lusaka Protocol-Angola

Peace Agreements Digital Collection Angola >> Lusaka Protocol Lusaka Protocol Lusaka, Zambia, November 15, 1994 The Government of the Republic of Angola (GRA) and the "União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola" (UNITA); With the mediation of the United Nations Organization, represented by the Special Representative of the Secretary-General of the United Nations in Angola, Mr. Alioune Blondin Beye; In the presence of the Representatives of the Observer States of the Angolan peace process: Government of the United States of America; Government of the Russian Federation; Government of Portugal; Mindful of: The need to conclude the implementation of the "Acordos de Paz para Angola" signed in Lisbon on 31 May 1991; The need for a smooth and normal functioning of the institutions resulting from the elections held on 29 and 30 September 1992; The need for the establishment of a just and lasting peace within the framework of a true and sincere national reconciliation; The relevant resolutions of the United Nations Security Council, Accept as binding the documents listed below, which constitute the Lusaka Protocol: Annex 1: Agenda of the Angola Peace Talks between the Government and UNITA; Annex 2: Reaffirmation of the acceptance, by the Government and UNITA, of the relevant legal instruments; Annex 3: Military Issues - I; Annex 4: Military Issues - II; Annex 5: The Police; Annex 6: National Reconciliation; Annex 7: Completion of the Electoral Process; Annex 8: The United Nations mandate and the role of the Observers of the "Acordos de Paz" and the Joint Commission; Annex 9: Timetable for the implementation of the Lusaka Protocol; Annex 10: Other matters. -

AFRICA 40 20 Dublin 0 20 Minsk 40 60 IRE

AFRICA 40 20 Dublin 0 20 Minsk 40 60 IRE. U.K. Amsterdam Berlin London Warsaw BELARUS RUSSIA NETH. KAZAKHSTAN Brussels GERMANY POLAND Kiev BEL. LUX. Prague N o r t h CZ. REP. UKRAINE Vol Aral SLOV. ga Sea Paris Bratislava Rostov A t l a n t i c Vienna MOL. Chisinau SWITZ. Bern AUS. Budapest Tashkent HUNG. Sea of FRANCE SLO. ROM. Odesa Azov Ljubljana CRO. Belgrade 40 O c e a n Milan Zagreb Bucharest UZBEKISTAN Marseilles BOS. & Danube AND. HER. SER.& Black Sea GEO. Caspian ITALYSarajevo MONT. Sofia Tbilisi Sea Ponta BULG. TURKMENISTAN PORTUGAL Barcelona Corsica Istanbul AZER. Delgada Rome Skopje ARM. Baku Ashgabat AZORES Madrid Tirana MACE. Ankara Yerevan (PORTUGAL) Lisbon Naples ALB. SPAIN Sardinia GREECE . Mashhad Izmir TURKEY Tabriz- Adana Algiers Tunis Sicily Athens Tehran Strait of Gibraltar Oran Aleppo AFG. MADEIRA ISLANDS Constantine Valletta Nicosia (PORTUGAL) Rabat SYRIA IRAQ Fès MALTA LEB. Esfahan- Casablanca CYPRUS Damascus ¸ Funchal TUNISIA Mediterranean Sea Beirut IRAN MOROCCO Baghdad Jerusalem Amman - CANARY ISLANDS Marrakech Tripoli Banghazi- - Alexandria ISRAEL Shiraz (SPAIN) Bandar Cairo JORDAN Kuwait - KUWAIT 'Abbas Al Jizah- Persian Las Palmas Nile Laayoune A L G E R I A Manama Gulf (El Aaiún) Abu BAHR. Dhabi Western L I B Y A EGYPT Riyadh Doha Muscat Medina Sahara QATAR U.A.E Al Jawf Aswan- Tropic of OMAN Cancer Admin. SAUDI boundary Jiddah 20 Nouadhibou ARABIA 20 Mecca MAURITANIA S A H A R A Port Red Sudan Sea CAPE VERDE Nouakchott Nile Tombouctou N I G E R Praia Agadez Omdurman ERITREA YEMEN Dakar MALI Arabian SENEGAL Khartoum Asmara Sanaa Banjul er CHAD Nig Niamey Zinder Sea Bamako BURKINA Lac'Assal Gulf of THE GAMBIA S U D A N Blue FASO (lowest point in Socotra N'Djamena Africa, -155 m) Djibouti Aden Bissau Kano (YEMEN) Ouagadougou Nile DJIBOUTI GUINEA-BISSAU GUINEA Nile Conakry BENIN E Y NIGERIA L Hargeysa GHANA White Addis L Freetown Abuja Moundou A CÔTE Volta Ababa TOGO Ogbomoso V SIERRA LEONE D'IVOIRE ue Prov. -

EKSC Airport Codes

EK airport codes AAE Annaba BTV Burlington DUS Dusseldorf ABJ Abidjan BUD Budapest DXB Dubai ABZ Aberdeen BUF Buffalo EAS San Sebastian ACC Accra CAI Cairo EBB Entebbe ADD Addis Ababa CAN Guangzhou EBL Ebril ADL Adelaide CBR Canberra ELS East London AGA Agadir CCJ Kozhikode EZE Buenos Aires AHB Abha CCU Kolkata FAO Faro AKL Auckland CDG Paris FAT Fresno ALC Alicante CFE Clermont-Ferrand FCO Rome ALG Algiers CGK Jakarta FLL Fort Lauderdale AMD Ahmedabad CHC Christchurch FNC Funchal AMM Amman CJB Peelamedu FRA Frankfurt AMS Amsterdam CKY Conarky FUK Fukuoka ANC Anchorage CLT Charlotte GAU Guwahati ARH Arkhangelsk CMB Colombo GBE Gaborone ARN Stockholm CMN Casablanca GDL Guadalajara ASU Asuncion CNF Belo Horizonte GIG Rio de Janeiro ATH Athens CNS Cairns GLA Glasgow ATL Atlanta CNX Chiang Mai GOI Goa AUS Austin COK Kochi GRJ George AZR Adrar COO Cotonou GRU Sao Paulo BAH Bahrain COR Cordoba GVA Geneva BCN Barcelona CPH Copenhagen GYN Goiania BEG Belgrade CPT Cape Town HAJ Hanover BEN Benghazi CTA Catania HAK Haikou BES Brest CTS Sapporo HAM Hamburg BEY Beirut CTU Chengdu HAN Hanoi BGW Baghdad CVG Cincinnati HBA Hobart BHD Belfast CWB Curitiba HEL Helsinki BHQ Broken Hill DAC Dhaka HGH Hangzhou BHX Birmingham DAD Da Nang HKG Hong Kong BIQ Biarritz DAM Damascus HKT Phuket BJL Banjul DAR Dar es Salaam HME Hassi Messaoud BKK Bangkok DCA Washington HND Tokyo BLL Billund DEL Delhi HOR Horta BLR Bengaluru (Bangalore) DEN Denver HPH Haiphong BMV Ban Me Thuot DFW Dallas/Fort Worth HRE Harare BNE Brisbane DKR Dakar HYD Hyderabad BOD Bordeaux DLC Dalian -

LEARNING from the CITY British Red Cross Urban Learning Project Scoping Study

LEARNING FROM THE CITY British Red Cross Urban Learning Project Scoping Study Acknowledgements This report was written by Amelia B. Kyazze, Paula Baizan and Samuel Carpenter, international division, British Red Cross. We are particularly grateful for the research support provided by Ellie Lewis. We also wish to thank our interviewees from the British Red Cross and the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, as well as members of the British Red Cross international division urban working group, for offering their time and insights. Thanks are also owed to Sara Pavanello, independent consultant, and Sonia Molina, Sorcha O’Callaghan and Ted Tuthill, British Red Cross, for reviewing earlier drafts of this study. Cover photo: Urban resident, Port-au-Prince, Haiti © British Red Cross Society 2 3 Contents Acknowledgements 2 Acronyms and abbreviations 6 Executive summary 7 1. Introduction 11 The British Red Cross Urban Learning Project 11 Study purpose and methodology 11 British Red Cross ways of working 12 2. The drive for better urban learning 13 The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and humanitarian action in urban areas 14 The British Red Cross and humanitarian action in urban areas 15 3. Urbanisation: trends and challenges 16 Understanding ‘urban’ and ’urbanisation’ 16 Responding to urban risk and vulnerability 18 Natural hazards 18 Urban violence and conflict 19 Markets and livelihoods 23 Health and water, sanitation and hygiene 23 Shelter, land and the built environment 25 4. New challenges, new approaches 26 Challenges and opportunities for the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement 26 Five ways forward for the British Red Cross 26 Sharpening context analysis and assessments 26 Understanding cash and markets better 28 Engaging and communicating with complex communities 32 Adapting to the challenges of land and the built environment 35 Engaging with urban systems and partnering with local groups and institutions 39 5. -

Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Land Use Land Cover Change in Lusaka City Using Geoinformatics Tools

The International Journal of Multi-Disciplinary Research ISSN: 3471-7102 Spatial Temporal Analysis of Land Use Land Cover Change in Lusaka City Using Geoinformatics Tools (Conference ID: CFP/371/2017) Alick Nguvulu Nicholas Okello Survey Department, School of Mines and Mineral Sciences Survey Department, School of Mines and Mineral Sciences Copperbelt University, P.O. Box 21692 Copperbelt University, P.O. Box 21692 Kitwe, Zambia Kitwe, Zambia [email protected] [email protected] Abstract— I. INTRODUCTION Analyzing the land use land cover (LULC) Land use land cover (LULC) change through change over time and space is important for effective rapid urbanization has been known to have such city space planning, monitoring and management effects as pollution from sewage, industrial especially in fast growing cities like Lusaka. effluent, urban run-off agricultural siltation, Nowadays, satellite based earth observation and localized air pollution and heat islands, monitoring has been used to detect, manage and overcrowding, traffic congestion due to monitor land use land cover changes over large areas inadequate infrastructure, high poverty levels of land. In the present study, we analyze the spatial- due to unemployment and poor social services temporal change of LULC for Lusaka City using classified Landsat imageries for 1995, 2005 and provision in water and sanitation electricity and 2015 in ERDAS Imagine 2014 and ArcGIS 10.2 solid waste disposal [1], [2]. It has also been environments. The classification is based on a noticed that urban land conversion leads to loss predefined LULC classification scheme consisting of of parcels of land earmarked for such purposes five classes, namely Industrial / Commercial / as recreation, open space and forest to built-up Residential, Water, Open/Unutilized Land, Miombo areas [3], [4]. -

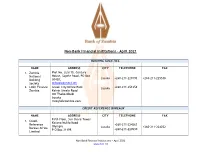

Non-Bank Financial Institutions – April 2021

Non-Bank Financial Institutions – April 2021 BUILDING SOCIETIES NAME ADDRESS CITY TELEPHONE FAX 1. Zambia Plot No. LUS/15, Century National House, Sapele Road, PO Box Lusaka +260-211-229191 +260-211-225510 Building 30420; Society [email protected] 2. LOLC Finance Green City Office Park Lusaka +260-211-251258 Zambia Kelvin Siwale Road Off Thabo Mbeki Lusaka [email protected] CREDIT REFERENCE BUREAUX NAME ADDRESS CITY TELEPHONE FAX Fifth Floor, Sun Share Tower 1. Credit Katima Mulilo Road Reference +260-211-224263 Olympia Bureau Africa Lusaka +260-211-224252 P O Box 31199, +260-211-220530 Limited Non-Bank Financial Institutions – April 2021 www.boz.zm DEVELOPMENT FINANCE INSTITUTIONS NAME ADDRESS CITY TELEPHONE FAX 1. Development Development House, Katondo Bank of Street, P.O. Box 33955; Lusaka +260-211-228576 +260-211-228588 Zambia [email protected] LEASING AND FINANCE COMPANIES NAME ADDRESS CITY TELEPHONE FAX 1. Agricultural Unit 214 B, Foxdale Court Office Leasing Park, Mama Betty Building Company 609 Zambezi Road Lusaka +260-969-785314 Zambia Limited 2. Alios Finance Stand No.20849,Corporate Park, +260-211-256592 Zambia Alick Nkhata Road P.O. Box Lusaka +260-211-256582 Limited 3370; [email protected] +260-211-256846 3. Betternow Plot No. LUS/1146, Lagos Road Finance Rhodes Pak Lusaka +260-211-295281 +260-211-295282 Company P.O. Box 32170, Limited [email protected] 4. Business Partners First Floor, Block 3,Corporate International Park, Alick Nkhata Road Lusaka +260-211-843277 +260-211-843277 Zambia SME PO Box 20849; Fund Limited Foxdale Forest, Zambezi Road, 5. -

COUNTRY SUMMARY for AFRICA May 2020

FUTURE CLIMATE COUNTRY SUMMARY FOR AFRICA May 2020 Summary of FCFA work in Zambia Future Climate for Africa (FCFA) aims to generate fundamentally new climate science focused on Africa, and to ensure that this science has an impact on human development across the continent. FCFA’s research in Zambia, was carried out in the capital city, Lusaka, by the FRACTAL consortium and led by the University of Zambia. Lusaka About FRACTAL FRACTAL (Future Resilience for African Cities and Lands) aimed to understand the decision context and the climate science required to contribute to climate-resilient Highlights from Lusaka development in nine southern African cities (Blantyre, Durban, Cape Town, Gaborone, Harare, Johannesburg, Lusaka, Maputo, Windhoek). The FRACTAL team aimed City Learning processes focused on water and climate to contribute to an advanced understanding of scientific change in the city, specifically the themes of water knowledge about climate processes, regional and local supply, groundwater pollution, groundwater levels and climate trends to improve understanding of southern flooding in peri-urban areas. Africa’s climate and work with decision-makers to integrate Learning Labs and City Dialogues were used to co- this scientific knowledge into climate-sensitive decisions at the city-regional scale (particularly decisions relating to explore issues around climate and water. water, energy and food with a lifetime of 5 to 40 years). Embedded Researcher seconded from city government supported learning processes and co-production of The project engaged with scientists, engineers, government policy briefs. representatives and other stakeholders. Working together, the researchers and stakeholders are co-producing relevant Climate Risk Narratives provided city with three possible knowledge that will support resilient development pathways future climate scenarios and enable decision-makers to better integrate pertinent climate knowledge into their resource management City-to-City learning exchanges provided decision- decisions and urban development planning. -

International Currency Codes

Country Capital Currency Name Code Afghanistan Kabul Afghanistan Afghani AFN Albania Tirana Albanian Lek ALL Algeria Algiers Algerian Dinar DZD American Samoa Pago Pago US Dollar USD Andorra Andorra Euro EUR Angola Luanda Angolan Kwanza AOA Anguilla The Valley East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antarctica None East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda St. Johns East Caribbean Dollar XCD Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine Peso ARS Armenia Yerevan Armenian Dram AMD Aruba Oranjestad Aruban Guilder AWG Australia Canberra Australian Dollar AUD Austria Vienna Euro EUR Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijan New Manat AZN Bahamas Nassau Bahamian Dollar BSD Bahrain Al-Manamah Bahraini Dinar BHD Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi Taka BDT Barbados Bridgetown Barbados Dollar BBD Belarus Minsk Belarussian Ruble BYR Belgium Brussels Euro EUR Belize Belmopan Belize Dollar BZD Benin Porto-Novo CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Bermuda Hamilton Bermudian Dollar BMD Bhutan Thimphu Bhutan Ngultrum BTN Bolivia La Paz Boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Sarajevo Marka BAM Botswana Gaborone Botswana Pula BWP Bouvet Island None Norwegian Krone NOK Brazil Brasilia Brazilian Real BRL British Indian Ocean Territory None US Dollar USD Bandar Seri Brunei Darussalam Begawan Brunei Dollar BND Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian Lev BGN Burkina Faso Ouagadougou CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Burundi Bujumbura Burundi Franc BIF Cambodia Phnom Penh Kampuchean Riel KHR Cameroon Yaounde CFA Franc BEAC XAF Canada Ottawa Canadian Dollar CAD Cape Verde Praia Cape Verde Escudo CVE Cayman Islands Georgetown Cayman Islands Dollar KYD _____________________________________________________________________________________________ -

BRIEFING NOTES for the SECRETARY-GENERAL 37Th Summit Meeting of OAU

BRIEFING NOTES FOR THE SECRETARY-GENERAL 37th Summit Meeting of OAU. Lusaka. Zambia Burundi The Secretary-General may wish to reiterate his support for the peace process and express hope that a breakthrough will be achieved at the Regional Summit in Arusha on 23 July 2001. There is a close linkage between the peace process and the development towards a democratic system based on the rule of law and the respect of human rights. The work of OHCHR Burundi is essential for the success of the peace process and therefore should be adequately supported. OHCHR Burundi has been strengthened in the last months in order to improve its capacity in Monitoring - 1 additional observers has been deployed and 2 more will be deployed hi July 2001. The Justice and Promotion sector will be strengthened as well. The Secretary-General may wish to address the issue of the establishment of "Commission on political prisoners" which was decided by the Implementation Monitoring Committee of the Arusha accord and to offer the assistance of OHCHR. OHCHR Office in Burundi has also been requested to assist in several other areas; elaboration of a legal framework which would allow the exercise of political freedoms; launching of an awareness campaign in order to ensure support for the peace process; establishment of a National Commission of rehabilitation and relocation of refugees and other victims; review of the provisions on temporary immunity in order to facilitate the return of refugees; review of legislation to combat crimes against humanity, including genocide. In addition to the above protection and promotion activities, OHCHR assists all UN partners in integrating human rights in their activities through a working group established to this effect. -

Africa Asia Australasia Europe Latin America Middle

PILATUS PC-12 ZS-JDD Introduced in 1994, the Pilatus PC12 is the largest civil single engine turbo-prop aircraft in production. With typical Swiss workmanship this aircraft offers a large cabin and versatility to load large items through the purpose designed aft loading door. It’s short take-off and landing capability ensure your party of leisure travellers will have direct access to remote safari lodges and project teams can be conveniently flown direct to site airfields in many cases. AFRICA ASIA AUSTRALASIA EUROPE LATIN AMERICA MIDDLE EAST Brazzaville Bujumbura Pointe-Noire Kinshasa Mombasa ANGOLA Tabora Tanga Matadi Kalemi TANZANIA Kananga Dar es Salaam Luanda Kamina Mbeya Malange Kasama Likasi Luena Lubumbashi Moroni MALAWI Antsiranana PILATUS PC-12 Huambo COMOROS Chipata MOZAMBIQUE ZAMBIA Lubango Lusaka Lilongwe Mongu Blantyre Nampula ANGOLA Livingstone Harare ZS-JDD Victoria Falls NAMIBIA Tsumeb Maun ZIMBABWE Antananarivo Tomasina Bulawayo Beira Francistown MADAGASCAR Windhoek Walvis Bay BOTSWANA Fianarantsoa Gaborone Pietersburg Tulear Pretoria Keetmanshoop Maputo Tolanaro Luederitz Johannesburg SWAZILAND Welkom Mbabane Kimberley Maseru Bloemfontein LESOTHO Durban SOUTH AFRICA De Aar Beaufort West Umtata Oudtshoorn East London Cape Town Port Elizabeth PILATUS PC-12 PILATUS PC-12 This map is a schematic representation only. CABIN CONFIGURATION RANGE OUT OF CAPE TOWN TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS: Registration ZS-JDD Base Cape Town, South Africa Year of Manufacture 2005 Number of Passengers 8 (including 2 x commuter seats) Crew 1 (with optional First Officer) Cruise Altitude 30,000 ft / 9,675 m Cruising Speed 240 kts / 445 km/hr Non-stop Range 1,000 nm / 2,220 km Galley No Lavatory Yes TRAVEL TIMES* JOURNEY NM KM FLIGHT TIME Cape Town - Windhoek 621 1,150 02 h 50 mins Cape Town - Maun 878 1,625 03 h 30 mins Cape Town - Bulawayo 993 1,837 03 h 55 mins *based on average winds from doors shut to doors open ExecuJet South Africa Charter, Tel: +27 11 516 2300, Fax: +27 11 659 2520, [email protected], www.execujet.com. -

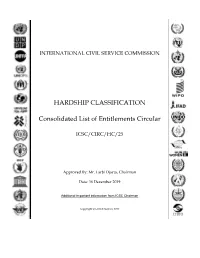

HARDSHIP CLASSIFICATION Consolidated List of Entitlements Circular

INTERNATIONAL CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION HARDSHIP CLASSIFICATION Consolidated List of Entitlements Circular ICSC/CIRC/HC/25 Approved By: Mr. Larbi Djacta, Chairman Date: 16 December 2019 Additional important information from ICSC Chairman Copyright © United Nations 2017 United Nations International Civil Service Commission (HRPD) Consolidated list of entitlements - Effective 1 January 2020 Country/Area Name Duty Station Review Date Eff. Date Class Duty Station ID AFGHANISTAN Bamyan 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG002 AFGHANISTAN Faizabad 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG003 AFGHANISTAN Gardez 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG018 AFGHANISTAN Herat 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG007 AFGHANISTAN Jalalabad 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG008 AFGHANISTAN Kabul 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG001 AFGHANISTAN Kandahar 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG009 AFGHANISTAN Khowst 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 E AFG010 AFGHANISTAN Kunduz 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG020 AFGHANISTAN Maymana (Faryab) 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG017 AFGHANISTAN Mazar-I-Sharif 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG011 AFGHANISTAN Pul-i-Kumri 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG032 ALBANIA Tirana 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 A ALB001 ALGERIA Algiers 01/Jan/2018 01/Jan/2018 B ALG001 ALGERIA Tindouf 01/Jan/2018 01/Jan/2018 E ALG015 ALGERIA Tlemcen 01/Jul/2018 01/Jul/2018 C ALG037 ANGOLA Dundo 01/Jul/2018 01/Jul/2018 D ANG047 ANGOLA Luanda 01/Jul/2018 01/Jan/2018 B ANG001 ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA St. Johns 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 A ANT010 ARGENTINA Buenos Aires 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 A ARG001 ARMENIA Yerevan 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019