Pancasila Ideology As a Field of Interpretation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Political Economy of Agriculture and Trade in Indonesia

Food, the State and Development: A Political Economy of Agriculture and Trade in Indonesia Benjamin Cantrell A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Studies University of Washington 2015 Committee: Sara Curran David Balaam Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Jackson School of International Studies ©Copyright 2015 Benjamin Cantrell ii University of Washington Abstract Food, the State and Development: A Political Economy of Agriculture and Trade in Indonesia Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Sara Curran, PhD Associate Professor Jackson School of International Studies Evans School of Public Affairs Global South economies experience significant political economic challenges to developing and implementing effective national development policy today. Many of these challenges are illustrated in the case of food policy in Indonesia, the subject of this study. After a period during which free trade and neoliberalism pervaded its national policy, Indonesia has experienced a rebirth of economic nationalism in national development. This is highlighted by food policies and political economic decisions being made at the national level focused on protection of domestic agricultural and trade sectors. This study applies qualitative research methods and historical analysis to understanding why this phenomena is taking place. This analysis explores intersections of state development, food security and globalization that influence policy–making, and identifies conflicting political -

Pancasila: Roadblock Or Pathway to Economic Development?

ICAT Working Paper Series February 2015 Pancasila: Roadblock or Pathway to Economic Development? Marcus Marktanner and Maureen Wilson Kennesaw State University www.kennesaw.edu/icat 1. WHAT IS PANCASILA ECONOMICS IN THEORY? When Sukarno (1901-1970) led Indonesia towards independence from the Dutch, he rallied his supporters behind the vision of Pancasila (five principles). And although Sukarno used different wordings on different occasions and ranked the five principles differently in different speeches, Pancasila entered Indonesia’s constitution as follows: (1) Belief in one God, (2) Just and civilized humanity, (3) Indonesian unity, (4) Democracy under the wise guidance of representative consultations, (5) Social justice for all the peoples of Indonesia (Pancasila, 2013). Pancasila is a normative value system. This requires that a Pancasila economic framework must be the means towards the realization of this normative end. McCawley (1982, p. 102) poses the question: “What, precisely, is meant by ‘Pancasila Economics’?” and laments that “[a]s soon as we ask this question, there are difficulties because, as most contributors to the discussion admit, it is all rather vague.” A discussion of the nature of Pancasila economics is therefore as relevant today as it was back then. As far as the history of Pancasila economic thought is concerned, McCawley (1982, p. 103ff.) points at the importance of the writings of Mubyarto (1938-2005) and Boediono (1943-present). Both have stressed five major characteristics of Pancasila economics. These characteristics must be seen in the context of Indonesia as a geographically and socially diverse developing country after independence. They are discussed in the following five sub-sections. -

Contemporary History of Indonesia Between Historical Truth and Group Purpose

Review of European Studies; Vol. 7, No. 12; 2015 ISSN 1918-7173 E-ISSN 1918-7181 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Contemporary History of Indonesia between Historical Truth and Group Purpose Anzar Abdullah1 1 Department of History Education UPRI (Pejuang University of the Republic of Indonesia) in Makassar, South Sulawesi, Indonesia Correspondence: Anzar Abdullah, Department of History Education UPRI (Pejuang University of the Republic of Indonesia) in Makassar, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. E-mail: [email protected] Received: May 28, 2015 Accepted: October 13, 2015 Online Published: November 24, 2015 doi:10.5539/res.v7n12p179 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/res.v7n12p179 Abstract Contemporary history is the very latest history at which the historic event traces are close and still encountered by us at the present day. As a just away event which seems still exists, it becomes controversial about when the historical event is actually called contemporary. Characteristic of contemporary history genre is complexity of an event and its interpretation. For cases in Indonesia, contemporary history usually begins from 1945. It is so because not only all documents, files and other primary sources have not been uncovered and learned by public yet where historical reconstruction can be made in a whole, but also a fact that some historical figures and persons are still alive. This last point summons protracted historical debate when there are some collective or personal memories and political consideration and present power. The historical facts are often provided to please one side, while disagreeable fact is often hidden from other side. -

A Lesson from Borobudur

5 Changing perspectives on the relationship between heritage, landscape and local communities: A lesson from Borobudur Daud A. Tanudirjo, Jurusan Arkeologi, Fakultas Ilmu Budaya, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta Figure 1. The grandeur of the Borobudur World Heritage site has attracted visitors for its massive stone structure adorned with fabulous reliefs and stupas laid out in the configuration of a Buddhist Mandala. Source: Daud Tanudirjo. The grandeur of Borobudur has fascinated almost every visitor who views it. Situated in the heart of the island of Java in Indonesia, this remarkable stone structure is considered to be the most significant Buddhist monument in the Southern Hemisphere (Figure 1). In 1991, Borobudur 66 Transcending the Culture–Nature Divide in Cultural Heritage was inscribed on the World Heritage List, together with two other smaller stone temples, Pawon and Mendut. These three stone temples are located over a straight line of about three kilometres on an east-west orientation, and are regarded as belonging to a single temple complex (Figure 2). Known as the Borobudur Temple Compound, this World Heritage Site meets at least three criteria of the Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention: (i) to represent a masterpiece of human creative genius, (ii) to exhibit an important interchange of human values over a span of time or within cultural area of the world, on developments in architecture or technology, monumental arts, town planning or landscape design, and (iii) to be directly or tangibly associated with events or living traditions, with ideas, or with beliefs, with artistic and literacy works of outstanding universal value (see also Matsuura 2005). -

From Custom to Pancasila and Back to Adat Naples

1 Secularization of religion in Indonesia: From Custom to Pancasila and back to adat Stephen C. Headley (CNRS) [Version 3 Nov., 2008] Introduction: Why would anyone want to promote or accept a move to normalization of religion? Why are village rituals considered superstition while Islam is not? What is dangerous about such cultic diversity? These are the basic questions which we are asking in this paper. After independence in 1949, the standardization of religion in the Republic of Indonesia was animated by a preoccupation with “unity in diversity”. All citizens were to be monotheists, for monotheism reflected more perfectly the unity of the new republic than did the great variety of cosmologies deployed in the animistic cults. Initially the legal term secularization in European countries (i.e., England and France circa 1600-1800) meant confiscations of church property. Only later in sociology of religion did the word secularization come to designate lesser attendance to church services. It also involved a deep shift in the epistemological framework. It redefined what it meant to be a person (Milbank, 1990). Anthropology in societies where religion and the state are separate is very different than an anthropology where the rulers and the religion agree about man’s destiny. This means that in each distinct cultural secularization will take a different form depending on the anthropology conveyed by its historically dominant religion expression. For example, the French republic has no cosmology referring to heaven and earth; its genealogical amnesia concerning the Christian origins of the Merovingian and Carolingian kingdoms is deliberate for, the universality of the values of the republic were to liberate its citizens from public obedience to Catholicism. -

Wayang Golek Menak: Wayang Puppet Show As Visualization Media of Javanese Literature

Wayang Golek Menak: Wayang Puppet Show as Visualization Media of Javanese Literature Trisno Santoso 1 and Bagus Wahyu Setyawan 2 {[email protected] 1, [email protected] 2} 1Institut Seni Indonesia Surakarta, Indonesia 2Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta, Indonesia Abstract. Puppet shows developing in Javanese culture is definitely various, including wayang kulit, wayang kancil, wayang suket, wayang krucil, wayang klithik, and wayang golek. This study was a developmental research, that developed Wayang Golek Ménak Sentolo with using theatre and cinematography approaches. Its aims to develop and create the new form of wayang golek sentolo show, Yogyakarta. The stages included conducting the orientation of wayang golek sentolo show, perfecting the concept, conducting FGD on the development concept, conducting the stage orientation, making wayang puppet protoype, testing the developmental product, and disseminating it in the show. After doing these stages, Wayang Golek Ménak Sentolo show gets developed from the original one, in terms of duration that become shorter, language using other languages than Javanese, show techniques that use theatre approach with modern blocking and lighting, voice acting of wayang figure with using dubbing techniques as in animation films, stage developed into portable to ease the movement as needed, as well as the form of wayang created differently from the original in terms of size and materials used. It is expected that the development and new form of wayang golek menak will get more acceptance from the modern community. Keywords: wayang golek menak, development, puppet show, visualization media, Javanese literature, serat menak. 1. INTRODUCTION Discussing about puppet shows in Java, there are two types of puppet shows, namely wayang golek and wayang krucil . -

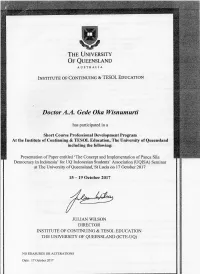

DEMOCRACY of PANCASILA: the CONCEPT and ITS IMPLEMENTATION in INDONESIA By: Dr

DEMOCRACY OF PANCASILA: THE CONCEPT AND ITS IMPLEMENTATION IN INDONESIA By: Dr. Drs. Anak Agung Gede Oka Wisnumurti, M.Si Faculty of Social and Political Science, Warmadewa University, Denpasar-Bali [email protected] Abstract Today democracy is regarded as the most ideal system of government. Many countries declare themselves to be democracies, albeit with different titles. Democracy in general is a system of government in which sovereignty is in the hands of the people, or is universally said to be government from, by and for the people. In Indonesia the democratic system used is the democracy of Pancasila. Democracy is based on the personality and philosophy of life of the Indonesian nation. Democracy based on Pancasila values, namely; based on the democracy led by the wisdom in the deliberations / representatives, having the concept of one god almighty upholding a just and civilized humanity, to unite Indonesia to bring about social justice for all Indonesians. The basic principle, prioritizing deliberation, with deliberations is expected to satisfy all those who differ, an expectation that is very difficult can be realized in the practice of nation and state. Implementation of Democrazy of Pancasila in the course of the nation's history, often experienced ups and downs. The applied democracy tends to deviate from the basic concept of the state, such as libral, guided, parliamentary and authoritarian practices. The 1998 reform order became the cornerstone of the democratic movement in Indonesia. The transition to a democratic system of government. If the implementation of this Pancasila democracy system can be realized, then Indonesia can be a model in the application of democratic system in governance. -

State and Revolution in the Making of the Indonesian Republic

Jurnal Sejarah. Vol. 2(1), 2018: 64 – 76 © Pengurus Pusat Masyarakat Sejarawan Indonesia https://doi.org/10.26639/js.v%vi%i.117 State and Revolution in the Making of the Indonesian Republic Norman Joshua Northwestern University Abstract While much ink has been spilled in the effort of explaining the Indonesian National Revolution, major questions remain unanswered. What was the true character of the Indonesian revolution, and when did it end? This article builds a case for viewing Indonesia’s revolution from a new perspective. Based on a revisionist reading of classic texts on the Revolution, I argue that the idea of a singular, elite-driven and Java-centric "revolution" dismisses the central meaning of the revolution itself, as it was simultaneously national and regional in scope, political and social in character, and it spanned more than the five years as it was previously examined. Keywords: Revolution, regionalism, elite-driven, Java-centric Introduction In his speech to Indonesian Marhaenist youth leaders in front of the Istana Negara on December 20, 1966, President Soekarno claimed that “[The Indonesian] revolution is not over!”1 Soekarno’s proposition calls attention to at least two different perspectives on revolution. On the one hand, the Indonesian discourse of a continuous revolution resonates with other permanent leftist revolutions elsewhere, such as the Cultural Revolution in Maoist China, Cuban Revolution in Castroist Cuba, or the Bolivarian 1 Soekarno, Revolusi belum selesai: kumpulan pidato Presiden Soekarno, 30 September 1965, pelengkap Nawaksara, ed. Budi Setiyono and Bonnie Triyana, Cetakan I (Jakarta: Serambi Ilmu Semesta, 2014), 759. Jurnal Sejarah – Vol. -

Kelasxii PPKN BS CRC.Indd

EDISI REVISI 2018 SMA/MA/ SMK/MAK KELAS XII Hak Cipta © 2018 pada Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Dilindungi Undang-Undang Disklaimer: Buku ini merupakan buku siswa yang dipersiapkan Pemerintah dalam rangka implementasi Kurikulum 2013. Buku siswa ini disusun dan ditelaah oleh berbagai pihak di bawah koordinasi Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, dan dipergunakan dalam tahap awal penerapan Kurikulum 2013. Buku ini merupakan “dokumen hidup” yang senantiasa diperbaiki, diperbarui, dan dimutakhirkan sesuai dengan dinamika kebutuhan dan perubahan zaman. Masukan dari berbagai kalangan diharapkan dapat meningkatkan kualitas buku ini. Katalog Dalam Terbitan (KDT) Indonesia. Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan. Pendidikan Pancasila dan Kewarganegaraan / Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan.-- . Jakarta : Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, 2018 xii, 140 hlm. : ilus. ; 25 cm. Untuk SMA/MA/SMK/MAK Kelas XII ISBN 978-602-427-090-2 (jilid lengkap) ISBN 978-602-427-093-3 (jilid 3) 1. Pendidikan Pancasila dan Kewarganegaraan -- Studi dan Pengajaran I. Judul II. Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan 600 Penulis : Yusnawan Lubis dan Mohamad Sodeli Penelaah : Dadang Sundawa, Nasiwan Pe-review : Ujang Suherman Penyelia Penerbitan : Pusat Kurikulum dan Perbukuan, Balitbang, Kemendikbud Cetakan ke-1, 2015 (ISBN 978-602-427-093-3) Cetakan Ke-2, 2018 (Edisi Revisi) Disusun dengan huruf Times New Roman, 12 pt. Kata Pengantar Pendidikan Pancasila dan Kewarganegaraan (PPKn) adalah mata pelajaran yang dirancang untuk membekali siswa dengan keimanan dan akhlak mulia sebagaimana diarahkan oleh falsafah hidup bangsa Indonesia yaitu Pancasila. Melalui pembelajaran PPKn, siswa dipersiapkan untuk dapat berperan sebagai warga negara yang efekƟ f dan bertanggung jawab. Oleh karena itu, dalam mapel ini membahas secara utuh materi Pancasila, Undang-Undang Dasar Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1945, Negara Kesatuan Republik Indonesia, dan Bhinneka Tunggal Ika. -

Revitalizing the Ideological Values of Pancasila As

Available online at http://www.pancaranpendidikan.or.id Pancaran Pendidikan Pancaran Pendidikan FKIP Universitas Jember DOI: Vol. 6, No. 3, Page 29-38, August, 2017 10.25037/pancaran.v6i3.34 ISSN 0852-601X e-ISSN 2549-838X Revitalizing The Ideological Values Of Pancasila As Antithesis Of Religious Radicalism Community Service In Karangduren Village Kebonarum Of Klaten Suryo Ediyono1 1Faculty of Cultural Sciences, Sebelas Maret University of Surakarta Email : [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: th The ideology of radical-terrorism is an interesting remark to be Received Date: 15 April 2017 understood by the Karangduren Klaten village community as an Received in Revised Form Date: th effort in preventing the entry value that is against the ideology of 30 April 2017 Pancasila. The supreme divinity value of Pancasila ideology one in Accepted Date: 15th May 2017 st the reform era has been challenged by the wave of globalization on Published online Date: 01 information. Socialization on the divinity values aims to stimulate August 2017 public awareness on the threat of radical ideology of terrorism that potentially grow and develop in the village of Karangduren, Key Words: Kebonarum, Klaten. This study covers the fields of nationalism and revitalizing, ideology pancasila, identity with the preaching method and focus of discussion. The nationalism, radical. Ideology of divinity axiologically and epistemologically comprising of divinity, humanity, unity, democratic and justice values which need to be delivered through specific form of communication which can be adjusted to community’s life in the village of Karangduren. Language as a tool in which various information can be accessed by people living in both rural and urban transition strongly influenced by factors of traditional cultural practices that are still upheld in dealing with modernity. -

Journal of Indonesian Tourism and Development Studies

Journal of Indonesian Tourism and p-ISSN: 2355-3979 Development Studies e-ISSN: 2338-1647 Journal of Indonesian Tourism and Development Studies EDITORIAL BOARD Chief Editor Luchman Hakim Ecotourism – Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, University of Brawijaya, Indonesia Team Editor Akira Kikuchi Yusri Abdillah Department of Environmental Faculty of Administrative Sciences University of Teknologi Malaysia, Malaysia University of Brawijaya, Indonesia Soemarno Soemarno Rukavina Baks Department of Soil Science Faculty of Agriculture Faculty of Agriculture University of Tadulako, Indonesia University of Brawijaya, Indonesia Regina Rosita Butarbutar Iwan Nugroho University of Sam Ratulangi, Indonesia Widyagama University – Indonesia Hasan Zayadi Devi Roza K. Kausar Department of Biology Faculty of Tourism Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Pancasila University, Indonesia Sciences Islamic University of Malang, Indonesia Managing Editor Muhammad Qomaruddin, Jehan Ramdani Haryati Aditya Dedy Purwito Editorial Address 2nd floor Building E of Graduate Program, Brawijaya University Mayor Jenderal Haryono street No. 169, Malang 65145, Indonesia Phone: +62341-571260 / Fax: +62341-580801 Email: [email protected] Website: jitode.ub.ac.id Journal of Indonesian Tourism and p-ISSN: 2355-3979 Development Studies e-ISSN: 2338-1647 TABLE OF CONTENT Vol. 4 No. 1, January 2016 The Floating Market of Lok Baitan, South Kalimantan Ellyn Normaleni ..................................................................................................................................................... -

The Practice of Pencak Silat in West Java

The Politics of Inner Power: The Practice of Pencak Silat in West Java By Ian Douglas Wilson Ph.D. Thesis School of Asian Studies Murdoch University Western Australia 2002 Declaration This is my own account of the research and contains as its main content, work which has not been submitted for a degree at any university Signed, Ian Douglas Wilson Abstract Pencak silat is a form of martial arts indigenous to the Malay derived ethnic groups that populate mainland and island Southeast Asia. Far from being merely a form of self- defense, pencak silat is a pedagogic method that seeks to embody particular cultural and social ideals within the body of the practitioner. The history, culture and practice of pencak in West Java is the subject of this study. As a form of traditional education, a performance art, a component of ritual and community celebrations, a practical form of self-defense, a path to spiritual enlightenment, and more recently as a national and international sport, pencak silat is in many respects unique. It is both an integrative and diverse cultural practice that articulates a holistic perspective on the world centering upon the importance of the body as a psychosomatic whole. Changing socio-cultural conditions in Indonesia have produced new forms of pencak silat. Increasing government intervention in pencak silat throughout the New Order period has led to the development of nationalized versions that seek to inculcate state-approved values within the body of the practitioner. Pencak silat groups have also been mobilized for the purpose of pursuing political aims. Some practitioners have responded by looking inwards, outlining a path to self-realization framed by the powers, flows and desires found within the body itself.