Pancasila: Roadblock Or Pathway to Economic Development?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Custom to Pancasila and Back to Adat Naples

1 Secularization of religion in Indonesia: From Custom to Pancasila and back to adat Stephen C. Headley (CNRS) [Version 3 Nov., 2008] Introduction: Why would anyone want to promote or accept a move to normalization of religion? Why are village rituals considered superstition while Islam is not? What is dangerous about such cultic diversity? These are the basic questions which we are asking in this paper. After independence in 1949, the standardization of religion in the Republic of Indonesia was animated by a preoccupation with “unity in diversity”. All citizens were to be monotheists, for monotheism reflected more perfectly the unity of the new republic than did the great variety of cosmologies deployed in the animistic cults. Initially the legal term secularization in European countries (i.e., England and France circa 1600-1800) meant confiscations of church property. Only later in sociology of religion did the word secularization come to designate lesser attendance to church services. It also involved a deep shift in the epistemological framework. It redefined what it meant to be a person (Milbank, 1990). Anthropology in societies where religion and the state are separate is very different than an anthropology where the rulers and the religion agree about man’s destiny. This means that in each distinct cultural secularization will take a different form depending on the anthropology conveyed by its historically dominant religion expression. For example, the French republic has no cosmology referring to heaven and earth; its genealogical amnesia concerning the Christian origins of the Merovingian and Carolingian kingdoms is deliberate for, the universality of the values of the republic were to liberate its citizens from public obedience to Catholicism. -

Wayang Golek Menak: Wayang Puppet Show As Visualization Media of Javanese Literature

Wayang Golek Menak: Wayang Puppet Show as Visualization Media of Javanese Literature Trisno Santoso 1 and Bagus Wahyu Setyawan 2 {[email protected] 1, [email protected] 2} 1Institut Seni Indonesia Surakarta, Indonesia 2Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta, Indonesia Abstract. Puppet shows developing in Javanese culture is definitely various, including wayang kulit, wayang kancil, wayang suket, wayang krucil, wayang klithik, and wayang golek. This study was a developmental research, that developed Wayang Golek Ménak Sentolo with using theatre and cinematography approaches. Its aims to develop and create the new form of wayang golek sentolo show, Yogyakarta. The stages included conducting the orientation of wayang golek sentolo show, perfecting the concept, conducting FGD on the development concept, conducting the stage orientation, making wayang puppet protoype, testing the developmental product, and disseminating it in the show. After doing these stages, Wayang Golek Ménak Sentolo show gets developed from the original one, in terms of duration that become shorter, language using other languages than Javanese, show techniques that use theatre approach with modern blocking and lighting, voice acting of wayang figure with using dubbing techniques as in animation films, stage developed into portable to ease the movement as needed, as well as the form of wayang created differently from the original in terms of size and materials used. It is expected that the development and new form of wayang golek menak will get more acceptance from the modern community. Keywords: wayang golek menak, development, puppet show, visualization media, Javanese literature, serat menak. 1. INTRODUCTION Discussing about puppet shows in Java, there are two types of puppet shows, namely wayang golek and wayang krucil . -

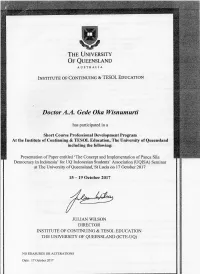

DEMOCRACY of PANCASILA: the CONCEPT and ITS IMPLEMENTATION in INDONESIA By: Dr

DEMOCRACY OF PANCASILA: THE CONCEPT AND ITS IMPLEMENTATION IN INDONESIA By: Dr. Drs. Anak Agung Gede Oka Wisnumurti, M.Si Faculty of Social and Political Science, Warmadewa University, Denpasar-Bali [email protected] Abstract Today democracy is regarded as the most ideal system of government. Many countries declare themselves to be democracies, albeit with different titles. Democracy in general is a system of government in which sovereignty is in the hands of the people, or is universally said to be government from, by and for the people. In Indonesia the democratic system used is the democracy of Pancasila. Democracy is based on the personality and philosophy of life of the Indonesian nation. Democracy based on Pancasila values, namely; based on the democracy led by the wisdom in the deliberations / representatives, having the concept of one god almighty upholding a just and civilized humanity, to unite Indonesia to bring about social justice for all Indonesians. The basic principle, prioritizing deliberation, with deliberations is expected to satisfy all those who differ, an expectation that is very difficult can be realized in the practice of nation and state. Implementation of Democrazy of Pancasila in the course of the nation's history, often experienced ups and downs. The applied democracy tends to deviate from the basic concept of the state, such as libral, guided, parliamentary and authoritarian practices. The 1998 reform order became the cornerstone of the democratic movement in Indonesia. The transition to a democratic system of government. If the implementation of this Pancasila democracy system can be realized, then Indonesia can be a model in the application of democratic system in governance. -

Kelasxii PPKN BS CRC.Indd

EDISI REVISI 2018 SMA/MA/ SMK/MAK KELAS XII Hak Cipta © 2018 pada Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Dilindungi Undang-Undang Disklaimer: Buku ini merupakan buku siswa yang dipersiapkan Pemerintah dalam rangka implementasi Kurikulum 2013. Buku siswa ini disusun dan ditelaah oleh berbagai pihak di bawah koordinasi Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, dan dipergunakan dalam tahap awal penerapan Kurikulum 2013. Buku ini merupakan “dokumen hidup” yang senantiasa diperbaiki, diperbarui, dan dimutakhirkan sesuai dengan dinamika kebutuhan dan perubahan zaman. Masukan dari berbagai kalangan diharapkan dapat meningkatkan kualitas buku ini. Katalog Dalam Terbitan (KDT) Indonesia. Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan. Pendidikan Pancasila dan Kewarganegaraan / Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan.-- . Jakarta : Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, 2018 xii, 140 hlm. : ilus. ; 25 cm. Untuk SMA/MA/SMK/MAK Kelas XII ISBN 978-602-427-090-2 (jilid lengkap) ISBN 978-602-427-093-3 (jilid 3) 1. Pendidikan Pancasila dan Kewarganegaraan -- Studi dan Pengajaran I. Judul II. Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan 600 Penulis : Yusnawan Lubis dan Mohamad Sodeli Penelaah : Dadang Sundawa, Nasiwan Pe-review : Ujang Suherman Penyelia Penerbitan : Pusat Kurikulum dan Perbukuan, Balitbang, Kemendikbud Cetakan ke-1, 2015 (ISBN 978-602-427-093-3) Cetakan Ke-2, 2018 (Edisi Revisi) Disusun dengan huruf Times New Roman, 12 pt. Kata Pengantar Pendidikan Pancasila dan Kewarganegaraan (PPKn) adalah mata pelajaran yang dirancang untuk membekali siswa dengan keimanan dan akhlak mulia sebagaimana diarahkan oleh falsafah hidup bangsa Indonesia yaitu Pancasila. Melalui pembelajaran PPKn, siswa dipersiapkan untuk dapat berperan sebagai warga negara yang efekƟ f dan bertanggung jawab. Oleh karena itu, dalam mapel ini membahas secara utuh materi Pancasila, Undang-Undang Dasar Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1945, Negara Kesatuan Republik Indonesia, dan Bhinneka Tunggal Ika. -

Revitalizing the Ideological Values of Pancasila As

Available online at http://www.pancaranpendidikan.or.id Pancaran Pendidikan Pancaran Pendidikan FKIP Universitas Jember DOI: Vol. 6, No. 3, Page 29-38, August, 2017 10.25037/pancaran.v6i3.34 ISSN 0852-601X e-ISSN 2549-838X Revitalizing The Ideological Values Of Pancasila As Antithesis Of Religious Radicalism Community Service In Karangduren Village Kebonarum Of Klaten Suryo Ediyono1 1Faculty of Cultural Sciences, Sebelas Maret University of Surakarta Email : [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: th The ideology of radical-terrorism is an interesting remark to be Received Date: 15 April 2017 understood by the Karangduren Klaten village community as an Received in Revised Form Date: th effort in preventing the entry value that is against the ideology of 30 April 2017 Pancasila. The supreme divinity value of Pancasila ideology one in Accepted Date: 15th May 2017 st the reform era has been challenged by the wave of globalization on Published online Date: 01 information. Socialization on the divinity values aims to stimulate August 2017 public awareness on the threat of radical ideology of terrorism that potentially grow and develop in the village of Karangduren, Key Words: Kebonarum, Klaten. This study covers the fields of nationalism and revitalizing, ideology pancasila, identity with the preaching method and focus of discussion. The nationalism, radical. Ideology of divinity axiologically and epistemologically comprising of divinity, humanity, unity, democratic and justice values which need to be delivered through specific form of communication which can be adjusted to community’s life in the village of Karangduren. Language as a tool in which various information can be accessed by people living in both rural and urban transition strongly influenced by factors of traditional cultural practices that are still upheld in dealing with modernity. -

Journal of Indonesian Tourism and Development Studies

Journal of Indonesian Tourism and p-ISSN: 2355-3979 Development Studies e-ISSN: 2338-1647 Journal of Indonesian Tourism and Development Studies EDITORIAL BOARD Chief Editor Luchman Hakim Ecotourism – Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, University of Brawijaya, Indonesia Team Editor Akira Kikuchi Yusri Abdillah Department of Environmental Faculty of Administrative Sciences University of Teknologi Malaysia, Malaysia University of Brawijaya, Indonesia Soemarno Soemarno Rukavina Baks Department of Soil Science Faculty of Agriculture Faculty of Agriculture University of Tadulako, Indonesia University of Brawijaya, Indonesia Regina Rosita Butarbutar Iwan Nugroho University of Sam Ratulangi, Indonesia Widyagama University – Indonesia Hasan Zayadi Devi Roza K. Kausar Department of Biology Faculty of Tourism Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Pancasila University, Indonesia Sciences Islamic University of Malang, Indonesia Managing Editor Muhammad Qomaruddin, Jehan Ramdani Haryati Aditya Dedy Purwito Editorial Address 2nd floor Building E of Graduate Program, Brawijaya University Mayor Jenderal Haryono street No. 169, Malang 65145, Indonesia Phone: +62341-571260 / Fax: +62341-580801 Email: [email protected] Website: jitode.ub.ac.id Journal of Indonesian Tourism and p-ISSN: 2355-3979 Development Studies e-ISSN: 2338-1647 TABLE OF CONTENT Vol. 4 No. 1, January 2016 The Floating Market of Lok Baitan, South Kalimantan Ellyn Normaleni ..................................................................................................................................................... -

Looking for the Form of Indonesian Democracy: Study of Pancasila Ideology Towards Concurrent Elections in 2024

Volume 2, Issue 4, April 2021 E-ISSN : 2686-6331, P-ISSN : 2686-6358 DOI: https://doi.org/10.31933/dijemss.v2i4 Received: 30h March 2021, Revised: 15th April 2021, Publish: 25th April 2021 LOOKING FOR THE FORM OF INDONESIAN DEMOCRACY: STUDY OF PANCASILA IDEOLOGY TOWARDS CONCURRENT ELECTIONS IN 2024 Osbin Samosir Lecturer in Political Science at FISIPOL, Christian University of Indonesia, Jakarta, [email protected] Corresponding Author: First Author Abstract: Indonesia’s democracy has taken huge leaps since the starting of reformation in 1998, compared to Soeharto’s authoritarian ruling (New Order) from 1966 to May 21, 1998, and during Soekarno’s ruling from the country’s independence in 1945 until 1966. One year after Soeharto’s fall on May 21, 1998, Indonesia held its first democratically election on June 7, 1999. The election was contested by 48 political parties. In 2004, Indonesia for the first time held its direct presidential election. One year later, Indonesia held its first regional elections, where voters directly elect governors, regents and mayors. The question is on whether the current democratic practices have been in accordance with all democratic values as intended by Pancasila ideology as the basic foundation for Indonesia in all political actions? Pancasila: 1). The belief in one God, 2). Just and civilized humanity, 3). Indonesian unity, 4. Democracy under the wise guidance of representative consultation, 5). Social justice for all peoples of Indonesia. The country’s founding fathers formulated the understanding of democracy based the traditional practices of democracy at the grassroots level which have lasted for centuries throughout the country. -

Digest #: Title

#8772 INDONESIA Grade Levels: 6-12 21 minutes AIMS MULTIMEDIA 1999 DESCRIPTION Located in the Indian Ocean, Indonesia has more than 17,000 islands and over 200 million people. Uses its three largest islands--Sumatra, Java, and Jakarta--to explore Indonesia's religions, government, people groups, arts, industries, and natural resources. Touches on a funeral ceremony, gathering sulfur, and the Komodo dragon. ACADEMIC STANDARDS Subject Area: Geography Standard: Understands the physical and human characteristics of place • Benchmark: Knows the human characteristics of places (e.g., cultural characteristics such as religion, language, politics, technology, family structure, gender; population characteristics; land uses; levels of development) Standard: Understands the nature and complexity of Earth's cultural mosaics • Benchmark: Understands the significance of patterns of cultural diffusion (e.g., the use of terraced rice fields in China, Japan, Indonesia, and the Philippines; the use of satellite television dishes in the United States, England, Canada, and Saudi Arabia) INSTRUCTIONAL GOALS 1. To review the history and resources of Indonesia. 2. To study the geographic features of Indonesia. 3. To illustrate the diversity of the people in Indonesia. BACKGROUND INFORMATION This ancient and diverse nation is rich in natural resources and has a hardworking citizenry. Under Dutch rule until the 1940s, Indonesia is now an independent nation operating under a republican form of government with three distinct branches: executive, legislative and judicial. 1 Captioned Media Program VOICE 800-237-6213 – TTY 800-237-6819 – FAX 800-538-5636 – WEB www.cfv.org Funding for the Captioned Media Program is provided by the U.S. Department of Education Jakarta, the capital city and located on the island of Java, is bustling, growing metropolis and home to nearly 12 million people. -

The Dynamic Interpretation of Pancasila in Indonesian State Administration History: Finding Its Authentic Interpretation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Jurnal Hukum Novelty P-ISSN: 1412-6834 E-ISSN: 2550-0090 Volume 11, Issue 01, 2020, pp. 39-55 The Dynamic Interpretation of Pancasila in Indonesian State Administration History: Finding Its Authentic Interpretation Wendra Yunaldi1 1 Faculty of Law, Universitas Muhammadiyah Sumatera Barat, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract Introduction to The Problem: The term interpretation of Pancasila seems rarely used to measure the substance of the Pancasila as the Indonesian nation’s weltanschauung. The term interpretation refers to the concept of constitutional and cultural meaning so that the order of civic life is in the same direction and under the paradigm of God, humanity, unity, society, and social justice. After the amendment of the 1945 Constitution, the Indonesian constitution has faced many changes. The changes that occurred are to creating a democratic governmental order. Even though the democratic rule of the government has surfaced, one thing for sure is that Pancasila is strengthening the form of Indonesia’s foundation. Because philosophy, enthusiasm, ideas, and thoughts of the nation’s life are determined by the underlying weltanschauung. Purpose/Objective Study: This study is trying to find the authentic interpretation of Pancasila based on its dynamic interpretation throughout Indonesian history. Design/Methodology/Approach: To answer these problems, the method used in this study is normative research with a conceptual approach so that interpretation is obtained by the paradigm built by the nation’s founders. Findings: By referring to library materials, the conclusion that can be drawn from this research is Pancasila, which is misinterpreted rigidly and is state-oriented to castrate the meaning of Pancasila as a public view of life. -

The Indonesia-China-Paradox: Indonesia's Variant of Capitalism, Its Embedding and Its Contrast to China

Goethe University Frankfurt, Germany Faculty of Social Science (FB03) Institute of Political Science Professorship for International Relations and International Political Economy Final dissertation for the reward of a Magister Artium Degree (M.A.). Topic: The Indonesia-China-Paradox: Indonesia's Variant of Capitalism, its Embedding and its Contrast to China. written under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Andreas Nölke & Prof. Dr. Heike Holbig by Dennis Fromm Frankfurt am Main, Germany Filing Date April 2012 Content List INTRODUCTION 1. RESEARCH DESIGN 1.1. Initial Question 1.2. Methodology 1.3. Latest State of the Art 1.4. Relevance 2. THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF INDONESIA 2.1. Paradoxes, Contradictions and Dialectics 2.2. Varieties of Capitalism according to Ten Brink 2.3. The Indonesian Variant of Capitalism 2.3.1. A Name for the Indonesian Capitalism I 2.3.2. Indonesian State Capitalism 2.3.3. Domestic Exploitation and Javanese Cultural Imperialism 2.3.4. Capitalism of a Failing State? 2.3.5. Special public-private Partnerships 2.3.6. Macro and Micro Economic Policies of Indonesia 2.3.7. Monetary and Financial Relations 2.3.8. Banking Sector and Capital Markets 2.3.9. Neo-Liberal or Neo-Traditional. From a Basket Case to a Special Case 2.3.10. Mechanisms of Social Sanction in Indonesian Bureaucracy 2.3.11. A Name for the Indonesian Capitalism II 2.3.12. Labour Relations in Indonesian Corporatism 2.3.13. Indonesia's Economy in International Contexts 2.3.14. The Failure of Exportism 2.3.15. Another Curse: Global Over-Accumulation and Foreign Investment 2.3.16. -

Factsheet: Indonesia's Pancasila

UNITED STATES COMMISSION on INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM FACTSHEET March 2021 INDONESIA’S PANCASILA Gayle Manchin Indonesia’s Pancasila Chair Tony Perkins By Patrick Greenwalt, Policy Analyst Vice Chair Anurima Bhargava Vice Chair Background Since its independence in 1945, Indonesia has promoted the state ideology of Pancasila Commissioners (literally, “five principles”), which comprises: monotheism, civilized humanity, national Gary Bauer unity, deliberative democracy, and social justice. Despite the general requirement of a monotheistic faith to fulfill the first principle, the government recognizes six religions James W. Carr as part of the Indonesian nation: Islam, Catholicism, Protestantism, Buddhism, Frederick A. Davie Hinduism, and Confucianism. Crucially, the state recognizes Sunnism as the only Nadine Maenza legitimate interpretation and expression of Islam. Johnnie Moore The concept of Pancasila was enshrined in the preamble to the 1945 constitution. Nury Turkel During the long, authoritarian period of President Suharto, (1967 until 1998), Pancasila became the focus of an effort to unite the country around broad principles instead of a single religious identity. However, since the transition to full democracy Erin D. Singshinsuk Executive Director following the resignation of Suharto in 1998, the prominence of state-sponsorship for the concept appeared to decline. During the same period, however, Indonesia has witnessed a continued the growth of hardline Islamist attitudes. USCIRF’s Mission In 1952, the Ministry of Religious Affairs limited the definition of monotheism but did not limit it to the Abrahamic traditions. That loose interpretation has allowed the Indonesian state to consider Confucian, Buddhist, and Hindu communities as in-line with this principle of Pancasila. It leaves no room, To advance international however, for other groups such as atheists and other nontheist communities. -

The Effect of Time Management in Shadow Puppet Performance On

ICLBI (2018) International Conference on Logistic and Business Innovation Volume 2020 Conference Paper The Effect of Time Management in Shadow Puppet Performance on the Audience Satisfaction Ribut Basuki1, Dwi Setiawan1, Theophilus Joko Riyanto1, and Zeplin Jiwa Husada Tarigan2 1Faculty of Languages and Literature, Petra Christian University, Siwalankerto 121-131, Surabaya 60236, Indonesia 2Faculty of Business and Economics, Petra Christian University , Siwalankerto 121-131, Surabaya 60236, Indonesia Abstract Indonesia has one of the greatest diversities in the world as reflected by its many cultures, languages, customs, and beliefs. This diversity can be easily seen in the East Java region which, despite its Javanese ethnic majority, is also populated by other ethnics, sub ethnics, and mixed groups. Shadow puppet theatre is a form of public attraction long existing in Java, even before the era of the Majapahit Empire. It is usually Corresponding Author: performed at night and takes a considerable time. In this multidisciplinary paper, it Ribut Basuki is hypothesized that good time management will increase audience satisfaction and [email protected] in turn contribute to the sustainability of the theatre and Javanese culture. Based on Received: 16 February 2020 the analysis of the survey, using partial least square by java web start programme, it Accepted: 5 March 2020 is found that, first, shadow puppet attraction positively affects to time management Published: 10 March 2020 as 0.720. Further, the attraction leads to audience satisfaction as 0.558. Lastly, time Publishing services provided by management affects audience satisfaction as 0.258 Knowledge E Keywords: Audience satisfaction; wayang attraction; wayang time management.