DREAMLAND a Novel and MODES of TEXTUAL DIVISION in THE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEAVING Hotill CALAFORNIX

LEAVING HOtILL CALAFORNIX Undamming the world’s rivers, forcing the collection of that which falls from the heavens and/or your ass, o camillo. An autobiographic historical expose, for Life. Introit I’m John Lawrence Kanazawa Jolley. Currently life on the planet is having a stroke, diagnosed from a human’s anatomy point of view, severe blockage of its flow ways. From life’s point of view humans are dam, slacker home building, ditch digging, drain the well dry, devil’s GMO food of the god’s, monocultural, sewage pumpers or porous dam sheddy flushtoile.t. ecocide artists. Compounding this problem is a machine/computer/vessel/organism that creates clone doppelganger pirates that’ve highjacked the surface guilty of the same crime. If we do anything well its intuitive container transportation. This is the case. I’m educated University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, Environmental Horticulture. I’m a trapper, gardener, carpenter, fisherperson, cooper and teacher. Drainage is the most important idea to consider when gardening. I paddled a canoe across North America and back, been through Lake Sacagawea twice. I’m a bullfighter, the foremost gardener in the world, the point spokesman for life, the man himself, hole puncher, obstacle remover, the pencil man, the one, Christ almighty. The character who appears again when it’s an “Obama nation of desolation” to save the world from damnation. I’m a specialist, designed specifically to solve the currentless dam problem. The timeliest, most intelligent, aggressive, offensive, desperate character ever created, for a reason. The health of life on the planet is in severe question. -

Psaudio Copper

Issue 116 JULY 27TH, 2020 “Baby, there’s only two more days till tomorrow.” That’s from the Gary Wilson song, “I Wanna Take You On A Sea Cruise.” Gary, an outsider music legend, expresses what many of us are feeling these days. How many conversations have you had lately with people who ask, “what day is it?” How many times have you had to check, regardless of how busy or bored you are? Right now, I can’t tell you what the date is without looking at my Doug the Pug calendar. (I am quite aware of that big “Copper 116” note scrawled in the July 27 box though.) My sense of time has shifted and I know I’m not alone. It’s part of the new reality and an aspect maybe few of us would have foreseen. Well, as my friend Ed likes to say, “things change with time.” Except for the fact that every moment is precious. In this issue: Larry Schenbeck finds comfort and adventure in his music collection. John Seetoo concludes his interview with John Grado of Grado Labs. WL Woodward tells us about Memphis guitar legend Travis Wammack. Tom Gibbs finds solid hits from Sophia Portanet, Margo Price, Gerald Clayton and Gillian Welch. Anne E. Johnson listens to a difficult instrument to play: the natural horn, and digs Wanda Jackson, the Queen of Rockabilly. Ken hits the road with progressive rock masters Nektar. Audio shows are on hold? Rudy Radelic prepares you for when they’ll come back. Roy Hall tells of four weddings and a funeral. -

Jerry Garcia Song Book – Ver

JERRY GARCIA SONG BOOK – VER. 9 1. After Midnight 46. Chimes of Freedom 92. Freight Train 137. It Must Have Been The 2. Aiko-Aiko 47. blank page 93. Friend of the Devil Roses 3. Alabama Getaway 48. China Cat Sunflower 94. Georgia on My Mind 138. It Takes a lot to Laugh, It 4. All Along the 49. I Know You Rider 95. Get Back Takes a Train to Cry Watchtower 50. China Doll 96. Get Out of My Life 139. It's a Long, Long Way to 5. Alligator 51. Cold Rain and Snow 97. Gimme Some Lovin' the Top of the World 6. Althea 52. Comes A Time 98. Gloria 140. It's All Over Now 7. Amazing Grace 53. Corina 99. Goin' Down the Road 141. It's All Over Now Baby 8. And It Stoned Me 54. Cosmic Charlie Feelin' Bad Blue 9. Arkansas Traveler 55. Crazy Fingers 100. Golden Road 142. It's No Use 10. Around and Around 56. Crazy Love 101. Gomorrah 143. It's Too Late 11. Attics of My Life 57. Cumberland Blues 102. Gone Home 144. I've Been All Around This 12. Baba O’Riley --> 58. Dancing in the Streets 103. Good Lovin' World Tomorrow Never Knows 59. Dark Hollow 104. Good Morning Little 145. Jack-A-Roe 13. Ballad of a Thin Man 60. Dark Star Schoolgirl 146. Jack Straw 14. Beat it on Down The Line 61. Dawg’s Waltz 105. Good Time Blues 147. Jenny Jenkins 15. Believe It Or Not 62. Day Job 106. -

Cathy Grier & the Troublemakers I'm All Burn CG

ad - funky biscuit … Frank Bang | Crazy Uncle Mikes Photo: Chris Schmitt 4 | www.SFLMusic.com 6 | www.SFLMusic.com Turnstiles | The Funky Biscuit Photo: Jay Skolnick Oct/Nov 2020 4. FRANK BANG 8. MONDAY JAM Issue #97 10. KEVIN BURT PUBLISHERS Jay Skolnick 12. DAYRIDE RITUAL [email protected] 18. VANESSA COLLIER Gary Skolnick [email protected] 22. SAMANTHA RUSSELL BAND EDITOR IN CHIEF Sean McCloskey 24. RED VOODOO [email protected] 28. CATHY GRIER SENIOR EDITOR Todd McFliker 30. LISA MANN [email protected] DISTRIBUTION MANAGER 32. LAURA GREEN Gary Skolnick [email protected] 34. MUSIC & COVID OPERATIONS MAGAGER 48. MONTE MELNICK Jessica Delgadillo [email protected] 56. TYLER BRYANT & THE SHAKEDOWN ADVERTISING [email protected] 60. SOCIALLY RESPONSIBLE FUN CONTRIBUTORS 62. THE REIS BROTHERS Brad Stevens Ray Anton • Debbie Brautman Message to our readers and advertisers Lori Smerilson Carson • Tom Craig Jessie Finkelstein As SFL Music Magazine adjusts to the events transpiring over the last several Peter “Blewzzman” Lauro weeks we have decided to put out the April issue, online only. We believe that Alex Liscio • Janine Mangini there is a need to continue to communicate what is happening in the music Audrey Michelle • Larry Marano community we love so dearly and want to be here for all of you, our readers Romy Santos • David Shaw and fellow concert goers and live music attendees, musicians, venues, clubs, Darla Skolnick and all the people who make the music industry what it is. SFL is dependent on its advertisers to bring you our “in print” all music maga- COVER PHOTO zine here in South Florida every month. -

Brand New Cd & Dvd Releases 2006 6,400 Titles

BRAND NEW CD & DVD RELEASES 2006 6,400 TITLES COB RECORDS, PORTHMADOG, GWYNEDD,WALES, U.K. LL49 9NA Tel. 01766 512170: Fax. 01766 513185: www. cobrecords.com // e-mail [email protected] CDs, DVDs Supplied World-Wide At Discount Prices – Exports Tax Free SYMBOLS USED - IMP = Imports. r/m = remastered. + = extra tracks. D/Dble = Double CD. *** = previously listed at a higher price, now reduced Please read this listing in conjunction with our “ CDs AT SPECIAL PRICES” feature as some of the more mainstream titles may be available at cheaper prices in that listing. Please note that all items listed on this 2006 6,400 titles listing are all of U.K. manufacture (apart from Imports which are denoted IM or IMP). Titles listed on our list of SPECIALS are a mix of U.K. and E.C. manufactured product. We will supply you with whichever item for the price/country of manufacture you choose to order. ************************************************************************************************************* (We Thank You For Using Stock Numbers Quoted On Left) 337 AFTER HOURS/G.DULLI ballads for little hyenas X5 11.60 239 ANATA conductor’s departure B5 12.00 327 AFTER THE FIRE a t f 2 B4 11.50 232 ANATHEMA a fine day to exit B4 11.50 ST Price Price 304 AG get dirty radio B5 12.00 272 ANDERSON, IAN collection Double X1 13.70 NO Code £. 215 AGAINST ALL AUTHOR restoration of chaos B5 12.00 347 ANDERSON, JON animatioin X2 12.80 92 ? & THE MYSTERIANS best of P8 8.30 305 AGALAH you already know B5 12.00 274 ANDERSON, JON tour of the universe DVD B7 13.00 -

MP3 Database.Wdb

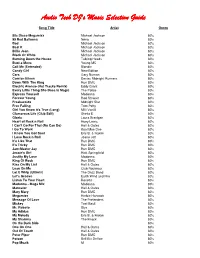

Audio Tech DJ's Music Selection Guide Song Title Artist Genre 80s Disco Megamixx Michael Jackson 80's 99 Red Balloons Nena 80's Bad Michael Jackson 80's Beat It Michael Jackson 80's Billie Jean Michael Jackson 80's Black Or White Michael Jackson 80's Burning Down the House Talking Heads 80's Bust a Move Young MC 80's Call Me (Extended) Blondie 80's Candy Girl New Edition 80's Cars Gary Numan 80's Com'on Eileen Dexies Midnight Runners 80's Down With The King Run DMC 80's Electric Avenue (Hot Tracks Remix) Eddy Grant 80's Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic The Police 80's Express Yourself Madonna 80's Forever Young Rod Stewart 80's Freakazoids Midnight Star 80's Free Falling Tom Petty 80's Girl You Know it's True (Long) Milli Vanilli 80's Glamorous Life (Club Edit) Sheila E 80's Gloria Laura Branigan 80's Heart of Rock n Roll Huey Lewis 80's I Can't Go For That (No Can Do) Hall & Oates 80's I Go To Work Kool Moe Dee 80's I Know You Got Soul Eric B. & Rakim 80's I Love Rock n Roll Joane Jett 80's It's Like That Run DMC 80's It's Tricky Run DMC 80's Jam-Master Jay Run DMC 80's Jessie's Girl Rick Springfield 80's Justify My Love Madonna 80's King Of Rock Run DMC 80's Kiss On My List Hall & Oates 80's Lean On Me Club Nouveau 80's Let It Whip (Ultimix) The Dazz Band 80's Let's Groove Earth Wind and Fire 80's Listen To Your Heart Roxette 80's Madonna - Mega Mix Madonna 80's Maneater Hall & Oates 80's Mary Mary Run DMC 80's Megamixx Herbie Hancock 80's Message Of Love The Pretenders 80's Mickey Toni Basil 80's Mr. -

Cypress Hill Still Smokin' Mp3, Flac, Wma

Cypress Hill Still Smokin' mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop / Rock Album: Still Smokin' Country: US Released: 2001 Style: Gangsta, Pop Rap MP3 version RAR size: 1930 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1781 mb WMA version RAR size: 1814 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 874 Other Formats: ADX MIDI MOD RA ASF MP1 VOC Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Program Start 2 How I Could Just Kill A Man (Live) 3 Insane In The Brain (Live) I Ain't Goin' Out Like That (Live) 4 Producer – T-Ray 5 Can't Get The Best Of Me (Live) 6 Hits From The Bong (Live) 7 Riot Starter (Live) 8 (Rock) Superstar (Live) 9 The Phuncky Feel One 10 How I Could Just Kill A Man 11 Hand On The Pump 12 Real Estate 13 Stoned Is The Way Of The Walk 14 Latin Lingo 15 Insane In The Brain 16 When Ship Goes Down I Ain't Goin' Out Like That 17 Producer – T-Ray 18 Throw Your Set In The Air Throw Your Hands In The Air 19 Featuring – Erick Sermon, MC Eiht, Redman 20 Illusions Boom Biddy Bye Bye (Fugees Remix) 21 Featuring – Wyclef JeanRemix – Wyclef Jean Tequila Sunrise 22 Featuring – Barron Ricks 23 Dr. Greenthumb 24 No Entiendes La Onda (How I Could Just Kill A Man) 25 (Rock) Superstar 26 Can't Get The Best Of Me Puppet Master 27 Rap – B-Real, Dr. Dre Credits Film Producer [Dvd] – Deana Concilio, Jason Bau Producer – DJ Muggs (tracks: 2 to 27) Notes Produced by Deana Concilio and Jason Bau. -

00:00:00 Music Transition “Crown Ones” Off the Album Stepfather by People Under the Stairs

00:00:00 Music Transition “Crown Ones” off the album Stepfather by People Under the Stairs. [Music continues under the dialogue, then fades out.] 00:00:06 Oliver Host Hello! I’m Oliver Wang. Wang 00:00:08 Morgan Host And I’m Morgan Rhodes. You’re listening to Heat Rocks. Rhodes 00:00:10 Oliver Host Every episode, we invite a guest to join us to talk about a heat rock: an album that just burns eternally. And today, we have something for the blunted as we dive back to 1991, to talk about the debut, self-titled album by Cypress Hill. 00:00:27 Music Music “Break It Up” from the album Cypress Hill by the band Cypress Hill. Light, multilayered rap. Break it up, Cypress Hill, break it up Cypress, break it up, Cypress Hill Cypress Hill! Break it up Cypress Hill, break it up Cypress, break it up Cypress Hill Cypress Hill! Break it up Cypress Hill, break it up Cypress, break it up Cypress Hill Cypress Hill! [Music continues under the dialogue briefly, then fades out.] 00:00:39 Oliver Host The first time I ever saw Cypress Hill was at my very first hip-hop show, in San Francisco in ’91. Cypress, however, were not the headliners. That would have been the trio of 3rd Bass, then touring behind their radio single, “Pop Goes the Weasel”. Cypress Hill was the opening act, with only a slow-burn B-side, “How I Could Just Kill a Man”, to their name at the time. Of course, a few years later and this would all change. -

Simplex SPECIAL Piano Player “IT MAKES MUSICIANS of US ALL” the Latest and Most Wonderful Invention in Automatic Piano Players

I' l,t ~ ....--------------------------The AJVlICA BULLETIN .. AUTOMATIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENT COLLECTORS' ASSOCIATION JULY/AUGUST 2001 VOLUME 38, NUMBER 4 24 Inches Long 16 Inches Deep 42 Inches High Simplex SPECIAL Piano Player “IT MAKES MUSICIANS OF US ALL” The Latest and Most Wonderful Invention in Automatic Piano Players. Compact – Ornamental – Capable of the Most Artistic Results As shown in the above illustration, the SIMPLEX SPECIAL does not come in contact with the keyboard. It does not interfere in any way with the ordinary uses of the piano. You can play the piano either with the aid of the SIMPLEX SPECIAL or in the ordinary manner without changing the position of the piano or player. It is so constructed that it is not necessary to cut, mar, or alter in any way the casing of the piano in making the attachment. Results obtained with the SIMPLEX SPECIAL are equal to those obtained with our regular SIMPLEX, and we feel we do not need to say more than that. The SIMPLEX SPECIAL is operated in the same manner as the SIMPLEX. Anybody can play more than five thousand selections of music on any piano by the aid of the SIMPLEX. Price of the Simplex Special, $300. Price of the Simplex, $250 Music Libraries at all principal Simplex agencies. SEND FOR CATALOGUE THEODORE P. BROWN, Manufacturer 5 MAY STREET, WORCESTER, MASS. THE AMICA BULLETIN AUTOMATIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENT COLLECTORS' ASSOCIATION Published by the Automatic Musical Instrument Collectors’ Association, a non-profit, tax exempt group devoted to the restoration, distribution and enjoyment of musical instruments using perforated paper music rolls and perforated music books. -

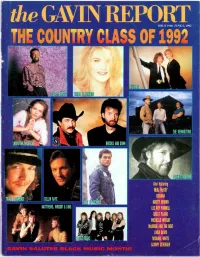

The GAVIN REPORT the COUNTRY CLASS of 1992

the GAVIN REPORT THE COUNTRY CLASS OF 1992 _; Also featuring NEAL McCOY DIXIANA COLLIN RAYE MARTY BROWN LEE ROY PARNELL GREAT PLAINS MICHELLE WRIGHT McBRIDE AND THE RIDE LINDA DAVIS MICHAEL WHITE SAMMY KERSHAW GAVIN e A K.lLITES BLACK MUSIC MdfleekrTlW In the dictionary, next to the wo -d "summer,' is a picture of the Love Shack. The video for "Roam" changed the way you eat bagels and bananas forever. Cosmic Thing comes to nearly four million pieces of history. T{ -at about cover; the last lime tl-e B -52's made a reco-d.Thisigk, the first ry direction. s Produced by Don Was Direct Manage -rent Group -Stemmei Jensen & Martin Krkup 9 ®' 992 Reprise Recoris. ft s a sock hop it +our own private Idc óo the GAVIN REPORT GAVIN AT A * Indicates Tie it» 4rv URBAN MOST ADDED MOST ADDED THE CURE EN VOGUE YO YO Friday I'm In Love (Fiction/Elektra) Giving Him Something He Can Feel (Atco/EastWest Home Girl Don't Play Dat (Atco/EastWest America) DEF LEPPARD America) ERIC B & RAKIM Make Love Like A Man (Mercury) TLC Don't Sweat The Technique (MCA) TOAD THE WET SPROCKET Baby -Baby -Baby (LaFace/Arista) X -CLAN Xodus (Polydor/PLG) All I Want (Columbia) ALYSON WILLIAMS Just My Luck (RAL/OBR/Columbia) HEAVY D. & THE BOYZ RECORD TO WATCH RECORD TO WATCH RETAIL MERYN CADELL DAVID BLACK You Can't See What I Can See The Swea er (Sire/Reprise) Nobody But You (Bust It/Capitol) (MCA) itAe RADIO SHANTE RICHARD MARX MARIAN CAREY Big Mama (Livin' Large/ Take This Heart (Capitol) I'll Be There (Columbia) Tommy Boy) COUNTRY MOST ADDED MOST ADDED MOST ADDED RICHARD -

112 Dance with Me 112 Peaches & Cream 213 Groupie Luv 311

112 DANCE WITH ME 112 PEACHES & CREAM 213 GROUPIE LUV 311 ALL MIXED UP 311 AMBER 311 BEAUTIFUL DISASTER 311 BEYOND THE GRAY SKY 311 CHAMPAGNE 311 CREATURES (FOR A WHILE) 311 DON'T STAY HOME 311 DON'T TREAD ON ME 311 DOWN 311 LOVE SONG 311 PURPOSE ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 1 PLUS 1 CHERRY BOMB 10 M POP MUZIK 10 YEARS WASTELAND 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 10CC THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 FT. SEAN PAUL NA NA NA NA 112 FT. SHYNE IT'S OVER NOW (RADIO EDIT) 12 VOLT SEX HOOK IT UP 1TYM WITHOUT YOU 2 IN A ROOM WIGGLE IT 2 LIVE CREW DAISY DUKES (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW DIRTY NURSERY RHYMES (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW FACE DOWN *** UP (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW ME SO HORNY (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW WE WANT SOME ***** (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 PAC 16 ON DEATH ROW 2 PAC 2 OF AMERIKAZ MOST WANTED 2 PAC ALL EYEZ ON ME 2 PAC AND, STILL I LOVE YOU 2 PAC AS THE WORLD TURNS 2 PAC BRENDA'S GOT A BABY 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE (EXTENDED MIX) 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE (NINETY EIGHT) 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE (ORIGINAL VERSION) 2 PAC CAN'T C ME 2 PAC CHANGED MAN 2 PAC CONFESSIONS 2 PAC DEAR MAMA 2 PAC DEATH AROUND THE CORNER 2 PAC DESICATION 2 PAC DO FOR LOVE 2 PAC DON'T GET IT TWISTED 2 PAC GHETTO GOSPEL 2 PAC GHOST 2 PAC GOOD LIFE 2 PAC GOT MY MIND MADE UP 2 PAC HATE THE GAME 2 PAC HEARTZ OF MEN 2 PAC HIT EM UP FT. -

Recording-1981-12.Pdf

nc hicrIng - °RC SOUND yotsi r $2.50 DECEMBER 1981 Z.<7 VC LUME 12 - NUMBER 6 ENGINEER PRODUCIR 104c, a:)43'pril"t 4S\\\ ru .4 rr First look: STUDER's Digital Multitrack aid Universal Sampling Convene' - Digital Up iate, page 105 60 MIMM11111111111111M1=11111.1111M 1111111111M11111MIIIIIII 50 IMMI11111111111111=111r new ININI111111111111111111411111IMIM1UMAIIIIIIIIIIIIMIll 111111111111111111111M11111111111RAMIVAIIIMIMMIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII /1111111/41111011111111111 40 NIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIMIAIIIP.11111411/.111111111111111111111111111111 e 1111111111111111111WAIIIIIINIIIMIUMIR1IUPIELIINIIMI111111111 1.1110111MIIMAINCIIIIM. ;1 30 11111111111MMBMIVallPAM'MPAIIMMIIIIINEMMII1111111111B1111111111/1111111111AIIIIMMIAlt.1111, :11 20 t M111111111111%111111/40 aleuwmAiumourdinnullissui z 411111111.1d111111M11111111111111 INNINOEIMIVAMIPINP.111rillrAINIMPP:4111111011MMPIIIIII MUM ,Inmilwall'APAITAMIIIIIKalINIIIIMMIMAIZMI 10 MNIPWIIK/111,741P MP 41111111111LIN /11111111Gal01111"noille"=well 0 or immunimmooulimd.seslemsonstionli 01 02 0.5 1 2 5 10 2C 50 100 200 500 1000 STATI L3AD 144,44s -nch Figure 2: Static deflection of lams is 1-iad- thick fiberglass pad on application of load in pounds per square inch, for ty-Tas of itabody Moist Control Company isolators. SHOWCO doing the 'Stones Tour, page 62 Floating Floors, page 80 RELATING RECORDING ART TO RECORDING SCIENCE TO RECORDING EQUIPMENT www.americanradiohistory.com EXI=DANEI YOUFI M01:11ZONS To reach the stars in this business you need two things, talent and exceptionally good equipment. The AMEK 2500 is State of the Art design and technology respected worldwide. In the past 12 months alone, we've placed consoles in Los Angeles, Dallas, NewYork, Nashville, London, Frank- furt, Munich, Paris, Milan, Tokyo, Sydney, Guatemala City, and johannesberg. When you have a great piece of equipment, word gets around. The "2500" has become an industry standard. It's everything you want in a master recording console, and ..