The State of Food Insecurity in Johannesburg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

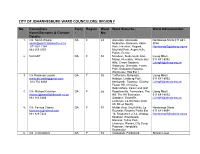

City of Johannesburg Ward Councillors: Region F

CITY OF JOHANNESBURG WARD COUNCILLORS: REGION F No. Councillors Party Region Ward Ward Suburbs: Ward Administrator: Name/Surname & Contact : : No: Details: 1. Cllr. Sarah Wissler DA F 23 Glenvista, Glenanda, Nombongo Sitela 011 681- [email protected] Mulbarton, Bassonia, Kibler 8094 011 682 2184 Park, Eikenhof, Rispark, [email protected] 083 256 3453 Mayfield Park, Aspen Hills, Patlyn, Rietvlei 2. VACANT DA F 54 Mondeor, Suideroord, Alan Lijeng Mbuli Manor, Meredale, Winchester 011 681-8092 Hills, Crown Gardens, [email protected] Ridgeway, Ormonde, Evans Park, Booysens Reserve, Winchester Hills Ext 1 3. Cllr Rashieda Landis DA F 55 Turffontein, Bellavista, Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Haddon, Lindberg Park, 011 681-8092 083 752 6468 Kenilworth, Towerby, Gillview, [email protected] Forest Hill, Chrisville, Robertsham, Xavier and Golf 4. Cllr. Michael Crichton DA F 56 Rosettenville, Townsview, The Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Hill, The Hill Extension, 011 681-8092 083 383 6366 Oakdene, Eastcliffe, [email protected] Linmeyer, La Rochelle (from 6th Street South) 5. Cllr. Faeeza Chame DA F 57 Moffat View, South Hills, La Nombongo Sitela [email protected] Rochelle, Regents Park& Ext 011 681-8094 081 329 7424 13, Roseacre1,2,3,4, Unigray, [email protected] Elladoon, Elandspark, Elansrol, Tulisa Park, Linmeyer, Risana, City Deep, Prolecon, Heriotdale, Rosherville 6. Cllr. A Christians DA F 58 Vredepark, Fordsburg, Sharon Louw [email protected] Laanglagte, Amalgam, 011 376-8618 011 407 7253 Mayfair, Paginer [email protected] 081 402 5977 7. Cllr. Francinah Mashao ANC F 59 Joubert Park Diane Geluk [email protected] 011 376-8615 011 376-8611 [email protected] 082 308 5830 8. -

Have You Heard from Johannesburg?

Discussion Have You Heard from GuiDe Johannesburg Have You Heard Campaign support from major funding provided By from JoHannesburg Have You Heard from Johannesburg The World Against Apartheid A new documentary series by two-time Academy Award® nominee Connie Field TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 about the Have you Heard from johannesburg documentary series 3 about the Have you Heard global engagement project 4 using this discussion guide 4 filmmaker’s interview 6 episode synopses Discussion Questions 6 Connecting the dots: the Have you Heard from johannesburg series 8 episode 1: road to resistance 9 episode 2: Hell of a job 10 episode 3: the new generation 11 episode 4: fair play 12 episode 5: from selma to soweto 14 episode 6: the Bottom Line 16 episode 7: free at Last Extras 17 glossary of terms 19 other resources 19 What you Can do: related organizations and Causes today 20 Acknowledgments Have You Heard from Johannesburg discussion guide 3 photos (page 2, and left and far right of this page) courtesy of archive of the anti-apartheid movement, Bodleian Library, university of oxford. Center photo on this page courtesy of Clarity films. Introduction AbouT ThE Have You Heard From JoHannesburg Documentary SEries Have You Heard from Johannesburg, a Clarity films production, is a powerful seven- part documentary series by two-time academy award® nominee Connie field that shines light on the global citizens’ movement that took on south africa’s apartheid regime. it reveals how everyday people in south africa and their allies around the globe helped challenge — and end — one of the greatest injustices the world has ever known. -

Economics of South African Townships: a Focus on Diepsloot

A WORLD BANK STUDY Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Economics of South African Townships Public Disclosure Authorized SPECIAL FOCUS ON DIEPSLOOT Public Disclosure Authorized Sandeep Mahajan, Editor Economics of South African Townships A WORLD BANK STUDY Economics of South African Townships Special Focus on Diepsloot Sandeep Mahajan, Editor WORLD BANK GROUP Washington, D.C. © 2014 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved 1 2 3 4 17 16 15 14 This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpreta- tions, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Rights and Permissions This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions: Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: Mahajan, Sandeep, ed. -

Braamfontein Aims to Be National Digital Hub

Views, Comments and Opinion Braamfontein aims to be national digital hub by Hans van de Groenendaal, features editor Prof. Barry Dwolatzky, director of the the Joburg Centre for Sofware Engineering at the University of the Witwatersrand believes in the value of an attractive and vibrant digital technolgy hub in Braamfontein to support skills development, job creation, entrepreneurship and the rejuvenation of Johanesburg's inner city. Braamfontein has seen much urban renewal in recent times, and is begining to regain its erstwhile trendiness. Prof. Barry Dwolatzky calls this new digital development the Tshimologong Precinct and is planning to create an exciting new-age software skills and innovation hub. Tshimologong is the seSotho for "place of new beginnings". The precinct is part of an ambitious ICT cluster development programme, Tech-in-Braam, aimed at turning the once dilapidated suburb into the new technical heart of South Africa and beyond. Prof. Dwolatzky is in the process of setting up shop in a series of five unused buildings. After some extensive refurbishments, a one-time night club floor will become a meeting space and will house server rooms; warehouses will be converted into computer labs and retail outlets will reincarnate as development pods. Braamfontein’s many advantages have made the neighbourhood an obvious The Tshimologong precinct will be developed in this part of Braamfontein. location for the precinct – it is convenient to two universities (the University of the Witwatersrand and the University of Johannesburg); it is centrally located with good public transport; it is the site of local government departments and many non-governmental organisations; and it is within easy reach of banks and mining houses, as well as a multitude of corporate headquarters. -

Johannesburg Spatial Development Framework 2040

City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality Spatial Development Framework 2040 In collaboration with: Iyer Urban Design, UN Habitat, Urban Morphology and Complex Systems Institute and the French Development Agency City of Johannesburg: Department of Development Planning 2016 Table of Contents Glossary of Terms.................................................................................................................................... 5 Abbreviations and Acronyms .................................................................................................................. 8 1. Foreword ....................................................................................................................................... 10 2. Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................... 11 2.1. Existing Spatial Structure of Johannesburg and its Shortcomings ........................................ 11 2.2. Transformation Agenda: Towards a Spatially Just City ......................................................... 12 2.3. Spatial Vision: A Compact Polycentric City ........................................................................... 12 2.4. Spatial Framework and Implementation Strategy ................................................................ 17 2.4.1. An integrated natural structure .................................................................................... 17 2.4.2. Transformation Zone ................................................................................................... -

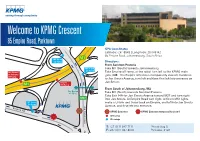

Welcome to KPMG Crescent

Jan Smuts Ave St Andrews M1 Off Ramp Winchester Rd Jan Smuts Off Ramp Welcome to KPMGM27 Crescent M1 North On Ramp De Villiers Graaff Motorway (M1) 85 Empire Road, Parktown St Andrews Rd Albany Rd GPS Coordinates Latitude: -26.18548 | Longitude: 28.045142 85 Empire Road, Johannesburg, South Africa M1 B M1 North On Ramp Directions: From Sandton/Pretoria M1 South Take M1 (South) towards Johannesburg On Ramp Jan Smuts / Take Empire off ramp, at the robot turn left to the KPMG main St Andrews gate. (NB – the Empire entrance is temporarily closed). Continue Off Ramp to Jan Smuts Avenue, turn left and then first left into entrance on Empire Jan Smuts. M1 Off Ramp From South of JohannesburgWellington Rd /M2 Sky Bridge 4th Floor Take M1 (North) towards Sandton/Pretoria Take Exit 14A for Jan Smuts Avenue toward M27 and turn right M27 into Jan Smuts. At Empire Road turn right, at first traffic lights M1 South make a U-turn and travel back on Empire, and left into Jan Smuts On Ramp M17 Jan Smuts Ave Avenue, and first left into entrance. Empire Rd KPMG Entrance KPMG Entrance temporarily closed Off ramp On ramp T: +27 (0)11 647 7111 Private Bag 9, Jan Jan Smuts Ave F: +27 (0)11 647 8000 Parkview, 2122 E m p ire Rd Welcome to KPMG Wanooka Place St Andrews Rd, Parktown NORTH GPS Coordinates Latitude: -26.182416 | Longitude: 28.03816 St Andrews Rd, Parktown, Johannesburg, South Africa M1 St Andrews Off Ramp Jan Smuts Ave Directions: Winchester Rd From Sandton/Pretoria Take M1 (South) towards Johannesburg Take St Andrews off ramp, at the robot drive straight to the KPMG Jan Smuts main gate. -

CITY of JOHANNESBURG – 24 May 2013 Structure of Presentation

2012/13 and 2013/14 BEPP/USDG REVIEW Portfolio Committee CITY OF JOHANNESBURG – 24 May 2013 Structure of Presentation 1. Overview of the City’s Development Agenda – City’s Urban Trends – Development Strategy and Approach – Capex process and implementation 2. Part One: 2012/13 Expenditure – Quarter One USDG expenditure 2012/13 – Quarter Two USDG expenditure 2012/13 – Quarter Three USDG expenditure 2012/13 – Quarter Four USDG expenditure 2012/13 – Recovery plan on 2012/13 USDG expenditure Part Two: 2013/14 Expenditure – Impact of the USDG for 2013/14 – Prioritization of 2013/14 projects 2 JOHANNESBURG DEMOGRAPHICS • Total Population – 4.4 million • 36% of Gauteng population • 8% of national population • Johanesburg is growing faster than the Gauteng Region • COJ population increase by 38% between 2001 and 2011. JOHANNESBURG POPULATION PYRAMID Deprivation Index Population Deprivation Index Based on 5 indicators: •Income •Employment •Health •Education •Living Environment 5 Deprivation / Density Profile Based on 5 indicators: •Income •Employment •Health •Education • Living Environment Development Principles PROPOSED BUILDINGS > LIBERTY LIFE,FOCUS AROUND MULTI SANDTON CITY SANDTON FUNCTIONAL CENTRES OF ACTIVITY AT REGIONAL AND LOCAL SCALE BARA TRANSPORT FACILITY, SOWETO NEWTOWN MAKING TRANSPORTATION WORK FOR ALL RIDGE WALK TOWARDS STRETFORD STATION BRT AS BACKBONE ILLOVO BOULEVARD BUILD-UP AROUND PUBLIC TRANSPORT NODESVRIVONIA ROADAND FACING LOWDENSGATE CORRIDORS URBAN RESTRUCTURING INVESTMENT IN ADEQUATE INFRASTRUCTURE IN STRATEGIC LOCATIONS -

Towards Applying a Green Infrastructure Approach in the Gauteng City-Region

GCRO RESEARCH REPORT # NO. 11 TOWARDS APPLYING A GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE APPROACH IN THE GAUTENG CITY-REGION DECEMBER 2019 Edited by Christina Culwick and Samkelisiwe Khanyile Contributions by Kerry Bobbins, Christina Culwick, Stuart Dunsmore, Anne Fitchett, Samkelisiwe Khanyile, Lerato Monama, Raishan Naidu, Gillian Sykes, Jennifer van den Bussche and Marco Vieira THE GCRO COMPRISES A PARTNERSHIP OF: TOWARDS APPLYING A GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE APPROACH IN THE GAUTENG CITY-REGION DECEMBER 2019 Production management: Simon Chislett ISBN:978-0-6399873-6-1 Cover image: Clive Hassall e-ISBN:978-0-6399873-7-8 Peer reviewer: Dr Pippin Anderson Edited by: Christina Culwick and Samkelisiwe Khanyile Copyright 2019 © Gauteng City-Region Observatory Contributions by: Kerry Bobbins, Christina Culwick, Published by the Gauteng City-Region Observatory Stuart Dunsmore, Anne Fitchett, Samkelisiwe Khanyile, (GCRO), a partnership of the University of Johannesburg, Lerato Monama, Raishan Naidu, Gillian Sykes, Jennifer the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, van den Bussche and Marco Vieira the Gauteng Provincial Government and organised local Design: Breinstorm Brand Architects government in Gauteng (SALGA). GCRO RESEARCH REPORT # NO. 11 TOWARDS APPLYING A GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE APPROACH IN THE GAUTENG CITY-REGION Edited by Christina Culwick and Samkelisiwe Khanyile Contributions by Kerry Bobbins, Christina Culwick, Stuart Dunsmore, Anne Fitchett, Samkelisiwe Khanyile, Lerato Monama, Raishan Naidu, Gillian Sykes, Jennifer van den Bussche and Marco Vieira -

Alexandra Urban Renewal:- the All-Embracing Township Rejuvenation Programme

ALEXANDRA URBAN RENEWAL:- THE ALL-EMBRACING TOWNSHIP REJUVENATION PROGRAMME 1. Introduction and Background About the Alexandra Township The township of Alexandra is one of the densely populated black communities of South Africa reach in township culture embracing cultural diversity. This township is located about 12km (about 7.5 miles) north-east of the Johannesburg city centre and 3km (less than 2 miles) from up market suburbs of Kelvin, Wendywood and Sandton, the financial heart of Johannesburg. It borders the industrial areas of Wynberg, and is very close to the Limbro Business Park, where large parts of the city’s high-tech and service sector are based. It is also very near to Bruma Commercial Park and one of the hype shopping centres of Eastgate Shopping Centre. This township amongst the others has been the first stops for rural blacks entering the city in search for jobs, and being neighbours with the semi-industrial suburbs of Kew and Wynberg. Some 170 000 (2001 Census: 166 968) people live in this community, in an area of approximately two square kilometres. Alexandra extends over an area of 800 hectares (or 7.6 square kilometres) and it is divided by the Jukskei River. Two of the main feeder roads into Johannesburg, N3 and M1 pass through Alexandra. However, the opportunity to link Alexandra with commercial and industrial areas for some time has been low. Socially, Alexandra can be subdivided into three parts, with striking differences; Old Alexandra (west of the Jukskei River) being the poorest and most densely populated area, where housing is mainly in informal dwellings and hostels. -

City of Johannesburg Pikitup

City of Johannesburg Pikitup Pikitup Head Office Private Bag X74 Tel +27(0) 11 712 5200 66 Jorissen Place, Jorissen St, Braamfontein Fax +27(0) 11 712 5322 Braamfontein Johannesburg www.pikitup.co.za 2017 2017 www.joburg.org.za DEPOT SUBURB/TOWNSHIP PRIORITY AREAS TO BE CLEARED ON FRIDAY, 05 FEB 2016 AVALON DEPOT Eldorado Park Ext 2 and Eldorado Park Proper (Michael Titus 083 260 1776) Eldorado Park Ext 10 and Proper Eldorado Park Ext 1, 3, and Bushkoppies Eldorado Park Ext 6 and 4 Eldorado Park Ext 4, Proper and Nancefield Industria Eldorado Park Ext 2, 3 and Bushkoppies Eldorado Park Ext 4 and Proper Eldorado Park Proper and M/Park Orange Farm Ext 3 and 1 Orange Farm Ext 1 and 2 Orange Farm Ext 1 and 2 Orange Farm Proper CENTRAL CAMP Selinah Pimville Zones 1 - 4 Tshablala 071 8506396 MARLBORO DEPOT Buccleuch ‘Nyane Motaung - 071 850 6395 Sandown City of Johannesburg Pikitup Pikitup Head Office Private Bag X74 Tel +27(0) 11 712 5200 66 Jorissen Place, Jorissen St, Braamfontein Fax +27(0) 11 712 5322 Braamfontein Johannesburg www.pikitup.co.za 2017 2017 www.joburg.org.za MIDRAND DEPOT Cresent wood, Erands gardens, Erands AH and Noordwyk South Jeffrey Mahlangu 082 492 8893 Juskeyview, Waterval estate, South , west and north NORWOOD DEPOT Bruma (Neil Observatory Macherson 071 Kensington 682 1450) Yeoville RANDBURG DEPOT Majoro Letsela Blairgowrie 082 855 9348 ROODEPOORT DEPOT Stella Wilson - Florida 071 856 6822 SELBY DEPOT Fordsburg Sobantwana Mkhuseli CBD 1: (Noord to Commissioner & End to Rissik Streets) 082 855 9321 CBD 2: (Rissik to -

Orange Farm Report.Indd

THE IMPACT OF THE COMMUNITY WORK PROGRAMME ON VIOLENCE IN ORANGE FARM Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation (CSVR) study on the Community Work Programme (CWP) Malose Langa August 2015 Acknowledgements This report is based on research carried out in Orange Farm in 2014. I would like to thank the many people, including staff and participants within the Community Work Programme and others, who contributed to the research by participating in interviews and focus groups and in other ways. The research was also supported by feedback from members of the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation (CSVR) Urban Violence Study Group, including Hugo van der Merwe, Themba Masuku, Jasmina Brankovic, Kindisa Ngubeni and David Bruce. Many others at CSVR also assisted with this work in one way or another. David Bruce assisted with the editing of the report. © September 2015, Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation 3rd Floor, Forum V, Braampark Office Park, 33 Hoofd Street, Braamfontein P O Box 30778, Braamfontein, 2017, South Africa; Tel: (011) 403-5650. Fax: (011) 388-0819. Email: [email protected]. CSVR website: http://www.csvr.org.za This work was carried out with financial support from the UK Government’s Department for International Development and the International Development Research Centre, Canada. The opinions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect those of DFID or IDRC. International Development Research Centre Centre de recherches pour le développement international Table of Contents Introduction -

Metropolis in Sophiatown Today, the Executive Mayor of the City Of

19 July 2013: Metropolis in Sophiatown Today, the Executive Mayor of the City of Johannesburg, Cllr Mpho Parks Tau, launched an Xtreme Park in Sophiatown while closing the annual Metropolis 2013 meeting held in Sandton, Joburg from Tuesday. At the launch, the Executive Mayor paid tribute to the vibrancy, multi-cultural and multi-racial buoyancy of Sophiatown, a place that became the lightning rod of both the anti-apartheid movement as well as the apartheid government's racially segregated and institutionalised policy of separate development. In February 1955 over 65 000 residents from across the racial divide were forcibly removed from Sophiatown and placed in separate development areas as they were considered to be too close to white suburbia. Sophiatown received a 48 hour Xtreme Park makeover courtesy of the City as part of its urban revitalisation and spatial planning programme. Said Mayor Tau: "The Xtreme Park concept was directed at an unused piece of land and turning it into a luscious green park. The park now consists of water features, play equipment for children, garden furniture and recreational facilities. Since 2007 the city has completed a number of Xtreme Parks in various suburbs including Wilgeheuwel, Diepkloof, Protea Glen, Claremont, Pimville and Ivory Park. As a result, Joburg's City Parks was awarded a gold medal by the United Nations International Liveable Communities award in 2008. "Today we are taking the Xtreme Parks concept into Sophiatown as part of our urban revitalisation efforts in this part of the city. Our objective is to take an under- utilised space, that is characterized by illegal dumping, graffiti, and often the venue for petty crime and alcohol and drug abuse; and transform it into a fully-fledged, multi-functional park," the Mayor said.