H.Doc. 108-224 Black Americans in Congress 1870-2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shoals Black History Educator Resource Packet

Shoals Black History Educator Resource Packet Muscle Shoals National Heritage Area Table of Contents Page 3: Introduction Page 4: Background Page 5: School Page 9: Religion Page 13: Work/Business Page 17: Community Page 18: Politics Page 25: People Page 29: Sports and Recreation Page 33: Music Page 37: Word Bank 2 Introduction This packet is the result of the Shoals Black History Project, a col- laborative effort between Project Say Something, the Florence- Lauderdale Public Library, and the University of North Alabama’s Pub- lic History Program. The Muscle Shoals National Heritage Area funded the project through their Community Grants Program. In the autumn of 2017, Project Say Something, in conjunction with the Florence- Lauderdale Public Library and students in the Public History program at UNA, hosted three history digitization events. At these events, com- munity members brought photographs, pamphlets, newspaper articles, documents, yearbooks, and other historical artifacts that were scanned and added to the public library’s online database. Volunteers also rec- orded oral histories at these events, and these recordings, along with typed transcripts, were added to the library’s database as well. This da- tabase can be accessed at: shoalsblackhistory.omeka.net. This effort seeks to incorporate African American history and life into the narrative of the Shoals area. In order for this history to be shared, it must first be gathered and organized; it can then be contextu- alized within national and regional trends and transformed into educa- tional resources that make sense of our common heritage and help us to better understand our present moment. -

Nicole Ives-Allison Phd Thesis

P STONES AND PROVOS: GROUP VIOLENCE IN NORTHERN IRELAND AND CHICAGO Nicole Dorothea Ives-Allison A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2015 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/6925 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence P Stones and Provos: Group Violence in Northern Ireland and Chicago Nicole Dorothea Ives-Allison This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 20 February 2015 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Nicole Dorothea Ives-Allison, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 83, 278 words in length, has been written by me, and that it is the record of work carried out by me, or principally by myself in collaboration with others as acknowledged, and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September, 2011 and as a candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (International Relations) in May, 2011; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2011 and 2014 (If you received assistance in writing from anyone other than your supervisor/s): I, Nicole Dorothea Ives-Allison, received assistance in the writing of this thesis in respect of spelling and grammar, which was provided by Laurel Anne Ives-Allison. -

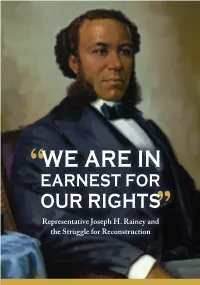

"We Are in Earnest for Our Rights": Representative

Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction On the cover: This portrait of Joseph Hayne Rainey, the f irst African American elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, was unveiled in 2005. It hangs in the Capitol. Joseph Hayne Rainey, Simmie Knox, 2004, Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction September 2020 2 | “We Are in Earnest for Our Rights” n April 29, 1874, Joseph Hayne Rainey captivity and abolitionists such as Frederick of South Carolina arrived at the U.S. Douglass had long envisioned a day when OCapitol for the start of another legislative day. African Americans would wield power in the Born into slavery, Rainey had become the f irst halls of government. In fact, in 1855, almost African-American Member of the U.S. House 20 years before Rainey presided over the of Representatives when he was sworn in on House, John Mercer Langston—a future U.S. December 12, 1870. In less than four years, he Representative from Virginia—became one of had established himself as a skilled orator and the f irst Black of f iceholders in the United States respected colleague in Congress. upon his election as clerk of Brownhelm, Ohio. Rainey was dressed in a f ine suit and a blue silk But the fact remains that as a Black man in South tie as he took his seat in the back of the chamber Carolina, Joseph Rainey’s trailblazing career in to prepare for the upcoming debate on a American politics was an impossibility before the government funding bill. -

Black & White in America: Political Cartoons on Race in the 1920S

BECOMING MODERN: AMERICA IN THE 1920S PRIMARY SOURCE COLLECTION * IN POLITICAL CARTOONS THE T WENTIES Eighteen political cartoons examining the racial issues confronting black and white Americans in the 1920s— the “race problem”—appear on the following pages. RACE They were published in general circulation (white- owned) and African American newspapers from 1919 to 1928. [Virulent racist depictions from the period are not included in this collection.] To analyze a political cartoon, consider its: CONTENT. First, basically describe what is drawn in the cartoon (without referring to the labels). What is depicted? What is happening? CONTEXT. Consider the timing. What is happening in national events at the time of the cartoon? Check the date: what occurred in the days and weeks before the cartoon appeared? LABELS. Read each label; look for labels that are not apparent at first, and for other written content in the cartoon. SYMBOLS. Name the symbols in the cartoons. What do they mean? How do they convey the cartoon’s “The U.S. Constitution Will Soon Be Bobtailed” meaning? The Afro-American, Jan. 18, 1924 TITLE. Study the title. Is it a statement, question, exclamation? Does it employ a well-known phrase, e.g., slang, song lyric, movie title, radio show, political or product slogan? How does it encapsulate and enhance the cartoonist’s point? TONE. Identify the tone of the cartoon. Is it satirical, comic, tragic, ironic, condemning, quizzical, imploring? What adjective describes the feeling of the cartoon? How do the visual elements in the drawing align with its tone? POINT. Put it all together. -

African American History in the Muscle Shoals National Heritage Area

African American History in the Muscle Shoals National Heritage Area Africans arrived in Alabama well before it became a state. In 1527, Pánfilo de Narvaez and six hundred men, including an unknown number of Christian African slaves (though at least two), left Spain on five ships with the intention of forming a permanent settlement in Florida. After a series of unfortunate events, the men landed in Mobile Bay, where one of the African slaves went to locate water for the crew. The man never returned to the ship and he inadvertently became the first black man to set foot in Alabama. Over the next three hundred years, more people of African descent traveled through and lived in what would become the state of Alabama. Some came of their own volition, however most arrived as slaves. The rich soil of the Tennessee River Valley attracted planters and farmers from Virginia, the Carolinas and Georgia. Because of poor field management practices, the soil in these eastern seaboard states had become worn out. Planters and farmers arrived in northwest Alabama, eager to grow crops, especially cotton. Many of them traveled to the region with slaves. While slavery in northwest Alabama did not reach the magnitude of slavery in the Black Belt region to the south, a significant portion of the population was enslaved. In 1818, when Alabama was still a territory, slaves made up 16 percent of the population of Franklin County and 13.6 percent of the population of Lauderdale County. By the eve of the Civil War, there were twenty three plantations in Lauderdale County with over fifty slaves. -

Elects Negro to City Council

A Newspaper » WrthA Constructive Policy s stanbaiud <' VOLUME 19, NUMBER 94 MEMPHIS, TENNESSEE, TUESDAY, MAY 15, 1951 PRICE FIVE CENTS >■1 X pr.;'Á? '•'À’ ELECTS NEGRO TO CITY COUNCIL . ' i.-’ j-..' At C.M E. Win After 30 Years NASHVILLE — (SNS) — Attorney Z. Alexander Looby, oneLof By C, E. CHAPMAN Dr. Martin Reports delivered response on behalf of the the nation's most prominent lawyers, was olected to the City Ij SHREVEPORT. La.—The General General Board delegation and Council of Nashville. He is the first Negro in 30 years to have gK Board of the Colored Methodist many visitors present. The distin K Episcopal Church held its 1961 ses- On Plans For New guished Bishop was vociferously a seat in the council. .' |8 slon here at Williams Institutional applauded for is fine words of wit The legal representative of the National Association for'tho S’ CME Church, 808 Butler St., last Hospital Campaign ticism and wisdom in response on Advancement of Colored People in Nashville, he defeated his gg Wednesday and Thursday and the behalf of the General Board and only opponent. Coyness L. Ennix. also a Negro. ® occasion seemed more like a Gen- Its huge delegation. The other H era! Conference than any other Welcoming program. Bishop Ber-. speakers were excellent. Music was Because of a recent Nashville M type of meeting, said one minister tram W. Doyle, presiding Bishop ot furnished by the musical groups of law which provides that Council who has been a regular attendant the Seventh Episcopal District, Lane Chapel CME Church and ths men be elected by the voters n «of the high bodies of the C. -

H.Doc. 108-224 Black Americans in Congress 1870-2007

H APPENDIX C H Black-American Representatives and Senators by State and Territory States are listed in descending order according to the number of African Americans that each has sent to Congress. STATE OR TERRITORY MEMBER’S NAME YEAR MEMBER TOOK OFFICE Illinois (16) Oscar Stanton De Priest 1929 Arthur Wergs Mitchell 1935 William Levi Dawson 1943 George Washington Collins 1970 Ralph Harold Metcalfe 1971 Cardiss Collins 1973 Bennett McVey Stewart 1979 Gus Savage 1981 Harold Washington 1981 Charles Arthur Hayes 1983 Carol Moseley-Brauna 1993 Mel Reynolds 1993 Bobby L. Rush 1993 Jesse L. Jackson, Jr. 1995 Danny K. Davis 1997 Barack Obamaa 2005 California (11) Augustus Freeman (Gus) Hawkins 1963 Ronald V. Dellums 1971 Yvonne Brathwaite Burke 1973 Julian Carey Dixon 1979 Mervyn Malcolm Dymally 1981 Maxine Waters 1991 Walter R. Tucker III 1993 Juanita Millender-McDonald 1996 Barbara Lee 1998 Diane Edith Watson 2001 Laura Richardson 2007 New York (9) Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. 1945 Shirley Anita Chisholm 1969 Charles B. Rangel 1971 Major Robert Odell Owens 1983 Edolphus Towns 1983 Alton R. Waldon, Jr. 1986 Floyd Harold Flake 1987 Gregory W. Meeks 1998 Yvette Diane Clarke 2007 766 H BLACK AMERICANS IN CONGRESS APPENDICES H PB STATE OR TERRITORY MEMBER’S NAME YEAR MEMBER TOOK OFFICE South Carolina (9) Joseph Hayne Rainey 1870 Robert Carlos De Large 1871 Robert Brown Elliott 1871 Richard Harvey Cain 1873 Alonzo Jacob Ransier 1873 Robert Smalls 1875 Thomas Ezekiel Miller 1890 George Washington Murray 1893 James Enos Clyburn 1993 Georgia (8) Jefferson Franklin Long 1870 Andrew Jackson Young, Jr. 1973 John R. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name The Forum other names/site number Forum Hall Name of Multiple Property Listing (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing) 2. Location rd street & number 318-328 East 43 Street not for publication city or town Chicago vicinity state Illinois county Cook zip code 60653 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide local Applicable National Register Criteria: A B C D Signature of certifying official/Title: Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer Date State Historic Preservation Office State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Blackwell-Israel Samuel A.M.E. Zion Church Building 3956 South Langley Avenue

LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT BLACKWELL-ISRAEL SAMUEL A.M.E. ZION CHURCH BUILDING 3956 SOUTH LANGLEY AVENUE Final Landmark Recommendation adopted by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks February 6, 2020 CITY OF CHICAGO Lori E. Lightfoot, Mayor Department of Planning and Development Maurice D. Cox, Commissioner 1 The Commission on Chicago Landmarks, whose nine members are appointed by the Mayor and City Council, was established in 1968 by city ordinance. The Commission is responsible for rec- ommending to the City Council which individual buildings, sites, objects, or districts should be desig- nated as Chicago Landmarks, which protects them by law. The landmark designation process begins with a staff study and a preliminary summary of information related to the potential designation criteria. The next step is a preliminary vote by the landmarks commission as to whether the proposed landmark is worthy of consideration. This vote not only initiates the formal designation process, but it places the review of city permits for the property under the jurisdiction of the Commission until a final landmark recommendation is acted on by the City Council. This Landmark Designation Report is subject to possible revision and amendment during the designation process. Only language contained within the designation ordinance adopted by the City Council should be regarded as final. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 4 Building Location Map 5 History of the Oakland Community Area and Bronzeville 6 Oakland Community Area 6 Bronzeville 9 History of Blackwell-Israel Samuel A.M.E. Zion Church 10 Oakland Methodist Episcopal Church: Initial Construction and Development 10 Blackwell Memorial A.M.E. -

BLACK HISTORY365 Courtesy of the AT&T Alabama African American History Calendar

BLACK HISTORY365 Courtesy of the AT&T Alabama African American History Calendar JANUARY volt in Louisiana, 1811. Rights Movement, was born in 22 Susan Rice confirmed as U.S. Am- Atlanta, Georgia, 1929. bassador to the U.N., the first 1 President Abraham Lincoln issues 9 Earl Gilbert Graves, Sr., publisher, African American female to hold Emancipation Proclamation, 1863. entrepreneur, philanthropist, and 16 Marcelite Jordan Harris, the first that position, 2009. founder of Black Enterprise maga- African American female general in 2 Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander, zine was born in Brooklyn, New the United States Air Force, was 23 Roots the television miniseries the first African American woman York, 1935. born in Houston, Texas, 1943. based on Alex Haley’s book Roots: to receive a Ph.D. in the United The Saga of an American Family, States, was born in Philadelphia, 1898. 10 George Washington Carver, agri- 17 Three-time heavyweight boxing began airing on ABC, 1977. cultural scientist, inventor, and champion Muhammad Ali was 3 William Tucker, the first recorded educator born in 1864. born in Louisville, Kentucky, 1942. 24 Jackie Robinson is first African African American born in the American elected to Baseball Hall American colonies, was born in 11 Reuben V. Anderson, first African 18 Dr. Daniel Hale Williams, pioneer of Fame, 1962. Jamestown, Virginia, 1624. American to be appointed to heart surgeon, was born in Mississippi Supreme Court, 1985. Hollidaysburg, Pennsylvania, 1856. 25 Black Entertainment Television be- 4 Grace Bumbry, opera singer, was gan broadcasting, 1980. born in St. Louis, Missouri, 1937. 12 U.S. Supreme Court rules that Afri- 19 John Harold Johnson, publisher can Americans have the right to (Ebony and Jet magazines), author, 26 Angela Yvonne Davis, political ac- 5 Alvin Ailey, Jr., hall of fame choreo- study law at state institutions, 1948. -

Mt. Olivet Baptist Church

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 05/31/2030) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name Mt. Olivet Baptist Church other names/site number Well Church Name of Multiple Property Listing African American Resources in Portland, Oregon, from 1851 to 1973 (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing) 2. Location street & number 1734 NE 1st Avenue not for publication city or town Portland vicinity state Oregon code OR county Multnomah code 051 zip code 97212 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth -

House of Representatives

370 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE MARCH 14 The PRESIDENT pro tempore. The Chair has held that country. The amendment I have suggested wm keep them it is not a substitute. on the roll, but will give the President the power to reduce Mr. HARRISON. Mr. President, in view of the fact that their compensation. there are several Senators who want to discuss at length Mr. McKELLAR. Mr. President, will the Senator yield? some amendments, I want to submit a unanimous-cQnsent Mr. DILL. I yield. request that when the Senate concludes its business tonight Mr. McKELLAR. I call the Senator's attention to the it shall recess until 12 o'clock noon tomorrow; that the bill last words of his amendment: be taken up at that hour and that no Senator shall speak But the President may reduce the rate of pension as he may longer th::m 30 minutes on the bill or longer than 15 min deem proper. utes on any amendment to the bill, and that no Senator That would mean that he could reduce it to any sum that shall speak mere than once on the bill. he might deem proper. The PRESIDENT pro tempore. Is there objection to the unanimous-consent request? Mr. DILL. Yes. Mr. LONG. I object. Mr. McKELLAR. When we apply the rule of 15 percent to other reductions, why should we make a distinction by Mr. McCARRAN. I object to the request. allowing the President to reduce to any amount he might Mr. BORAH. Mr. President, may I be permitted to say see fit or to cut off entirely the pensions received by Spanish .