Sir William Crookes (1832–1919) Biography with Special Reference to X-Rays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Henry Ford NERS/BIOE 481 Lecture 01 Introduction

NERS/BIOE 481 Lecture 01 Introduction Michael Flynn, Adjunct Prof Nuclear Engr & Rad. Science Henry Ford Health System [email protected] [email protected] RADIOLOGY RESEARCH I.A – Imaging Systems (6 charts) A) Imaging Systems 1) General Model 2) Medical diagnosis 3) Industrial inspection NERS/BIOE 481 - 2019 2 I.A.1 - General Model – xray imaging Xrays are used to examine the interior content of objects by recording and displaying transmitted radiation from a point source. DETECTION DISPLAY (A) Subject contrast from radiation transmission is (B) recorded by the detector and (C) transformed to display values that are (D) sent to a display device for (E) presentation to the human visual system. NERS/BIOE 481 - 2019 3 I.A.2 - Medical Radiographs Traditional Modern Film-screen Digital Radiograph Radiograph NERS/BIOE 481 - 2019 4 I.A.1 - General Model – radioisotope imaging Radioisotope imaging differs from xray imaging only with repect to the source of radiation and the manner in which radiation reaches the detector DETECTION DISPLAY A B Pharmaceuticals tagged with radioisotopes accumulate in target regions. The detector records the radioactivity distribution by using a multi-hole collimator. NERS/BIOE 481 - 2019 5 I.A.2 - Medical Radisotope image Radioisotope image depicting the perfusion of blood into the lungs. Images are obtained after an intra-venous injection of albumen microspheres labeled with technetium 99m. Anterior Posterior NERS/BIOE 481 - 2019 6 I.A.3 - Industrial Radiography – homeland security Aracor Eagle High energy x-rays and a linear detector are used to scan large vehicles for border inspection NERS/BIOE 481 - 2019 7 I.A.3 - Industrial radiography – battery CT CT image of a lithium battery (Duracell CR2) “Tracking the dynamic morphology of active materials Finegan during operation of et.al., lithium batteries is Advanced essential for Science, identifying causes 2016 (3). -

A Compact Guide

A Compact Guide TO Dr. HAKIM’s COLLECTION OF ANTIQUE X-RAY TUBES AND ACCESSORIES October 2014 INDEX Page Number Crookes Tubes……………………………... 1 Cold Cathode Ion X-Ray Tubes…………… 2-3-4-5 Cold Cathode Rectifier Valves…………….. 6 Air-Cooled Hot Cathode ( Coolidge ) X-Ray Tubes……………………………………….. 7-8-9 Oil-Immersed Hot-Cathode Fixed Anode Tubes, Unusual Tubes, and Tubes with Special Functions ………………………….. 9-10-11 Air-Cooled Kenotrons ( Rectifier Valves )….. 13-14 Oil-Immersed Kenotrons ( Rectifier Valves ).. 15-16-17 Radiology-Related Items…………………... 18-19-20- 21-22 1 Crookes Tubes Early basic type Crookes tube This is a 20 th Century replica of the Crookes tube with which W.C.Roëntgen was experimenting when he discovered an unknown type of rays which he called “x”rays Experimental multi-electrode Crookes tube (One cathode and three anodes ). Early 20 th Century Adjustable vacuum multi-electrode discharge tube, with two cathodes ( in the long arms ), one flat anode on top of the spherical bulb, and an anti-cathode in the centre of the sphere, covered with platinum foil Experimental Crookes tube for studying the deflection of cathode rays in a magnetic field 2 Cold Cathode Ion X-Ray Tubes The “ Jackson Tube ”, the earliest two electrode “Focus X-Ray Tube”, (concave aluminum cathode and flat platinum anti-cathode ) 1896 Late 19 th Century or early 20 th Century three electrode focus x-ray tube (Aluminium concave cathode, flat aluminium anode, and thin platinum anti-cathode). No Regeneration. Early 20 th Century x-ray tube similar in conception to the tube above, but with an aluminium rod anode, and of a more recent make No regeneration Very rare late 19 th Century 3 electrode cylindrical x-ray tube. -

May 2016 Alan J. Rocke EDUCATION BA, 1969, Chemistry, Beloit College

-1- May 2016 Alan J. Rocke EDUCATION B.A., 1969, Chemistry, Beloit College, Beloit, Wisconsin M.A., 1973, History of Science, University of Wisconsin-Madison Thesis: “Isaac Newton’s Theory of Matter” University of Munich, West Germany, 1974-75 Ph.D., 1975, History of Science, University of Wisconsin-Madison Dissertation: “Origins of the Structural Theory in Organic Chemistry” ACADEMIC EMPLOYMENT University of Wisconsin-Madison 1969-74 Teaching Assistant, Depts. of Chemistry and History of Science 1975-78 Lecturer, Depts. of Chemistry and Integrated Liberal Studies Case Western Reserve University 1978-84 Assistant Professor of History of Science and Technology, Department of Interdisciplinary Studies 1984-93 Associate Professor of History of Technology and Science 1993-2016 Professor of History 1995-2016 Henry Eldridge Bourne Professor of History 2012- Distinguished University Professor AWARDS AND HONORS Jack Youden Prize (American Society for Quality Control, Chemical Division), 1982 Carl F. Wittke Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching, 1988 Outstanding Paper Award (American Chemical Society, History Division), 1992 Dexter Award for Outstanding Lifetime Contributions to the History of Chemistry (American Chemical Society), 2000 Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, 2000 Liebig-Wöhler Freundschafts-Preis, Lewicki Foundation, Göttingen, 2002 Membre correspondant, Académie Internationale d’Histoire des Sciences, 2007 Fellow of the American Chemical Society, 2012 Distinguished University Professor, 2012 -

Atomic Theory - Review Sheet

Atomic Theory - Review Sheet You should understand the contribution of each scientist. I don't expect you to memorize dates, but I do want to know what each scientist contributed to the theory. Democretus - 400 B.C. - theory that matter is made of atoms Boyle 1622 -1691 - defined element Lavoisier 1743-1797 - pioneer of modern chemistry (careful and controlled experiments) - conservation of mass (understand his experiment and compare to the lab "Does mass change in a chemical reaction?") Proust 1799 - law of constant composition (or definite proportions) - understand this law and relate it to the Hydrogen and Oxygen generation lab Dalton 1808 - Understand the meaning of each part of Dalton's atomic theory. - You don't have to memorize the five parts, just understand what they mean. - You should know which parts we now know are not true (according to modern atomic theory). Black Box Model Crookes 1870 - Crookes tube - Know how this is constructed (Know how cathode rays are generated and what they are.) J.J. Thomsen - 1890 - How did he expand on Crookes' experiment? - discovered the electron - negative particles in all of matter (all atoms) - must also be positive parts Lord Kelvin - near Thomsen's time Plum Pudding Model - plum pudding model Henri Becquerel - 1896 - discovered radioactivity of uranium Marie Curie - 1905 - received Nobel prize (shared with her husband Pierre Curie and Henri Bequerel) for her work in studying radiation. - Name the three kinds of radiation and describe each type. Rutheford - 1910 - Understand the gold foil experiment - How was it set up? - What did it show? - Discovered the proton Hard Nucleus Model - new model of atom (positively charged, very dense nucleus) Niels Bohr - 1913 - Bohr model of the atom - electrons in specific orbits with specific energies James Chadwick - 1932 - discovered the electron Modern version of atom - 1950 Bohr Model - similar nucleus (protons + neutrons) - electrons in orbitals not orbits Bohr Model Understand isotopes, atomic mass, mass #, atomic #, ions (with neutrons) Nature of light - wavelength vs. -

The Cathode Ray Tube 1

Kendall Dix The Cathode Ray Tube 1 PHYSICS II HONORS PROJECT THE CATHODE RAY TUBE BY: KENDALL DIX 001-H ID: 010363995 Kendall Dix The Cathode Ray Tube 2 Introduction !The purpose of this construction project was the replication of Crookes tube, or the cathode ray tube. I was inspired by the historical and modern significance of the cathode ray. A modification of Crookes tube evolved into the first televisions. Although these are being phased out, their importance is undeniable. In modern times the basic cathode ray is not used for anything but demonstrating gasses conducting electricity. How it should work !A Crookes tube is constructed by applying a voltage from a few kV to 100 kV between a cathode and anode (Gilman). Although the Crookes tube requires an evacuation of gas, it must not be complete. The remaining gas is crucial to the process. The cathode (negative side) is induced to emit electrons by naturally occurring positive ions in the air (Townsend). The positive ions are attracted to the negative charge of the cathode. They collide with other air particles and strip off electrons, creating more positive ions. The positive ions collide with the cathode so powerfully that they knock off the excess electrons. These electrons are immediately attracted to the anode and begin accelerating toward it. Because Crookes tube is a cold cathode (no heat applied), the cathode requires the impact of the ions to knock off electrons. The maximum vacuum or minimum gas pressure to begin the chain reaction of ions in the gas is about 10-6 atm (Thompson). -

One Century of Cosmic Rays – a Particle Physicist\'S View

EPJ Web of Conferences 105, 00001 (2015) DOI: 10.1051/epjconf/201510500001 c Owned by the authors, published by EDP Sciences, 2015 One century of cosmic rays – A particle physicist’s view Christine Suttona CERN, 1211 Geneva 23, Switzerland Abstract. Experiments on cosmic rays and the elementary particles share a common history that dates back to the 19th century. Following the discovery of radioactivity in the 1890s, the paths of the two fields intertwined, especially during the decades after the discovery of cosmic rays. Experiments demonstrated that the primary cosmic rays are positively charged particles, while other studies of cosmic rays revealed various new sub-atomic particles, including the first antiparticle. Techniques developed in common led to the birth of neutrino astronomy in 1987 and the first observation of a cosmic γ -ray source by a ground-based cosmic-ray telescope in 1989. 1. Introduction remove the air led to the discovery of “cathode rays” emitted from the cathode at one end of the tube. In 1879, in “There are more things in heaven and earth than are the course of investigations in England, William Crookes dreamt of in your philosophy ...” (Hamlet, William discovered that the speed of the discharge along the length Shakespeare). of a vacuum tube decreased as he reduced the pressure. This indicated that ionization of the air was causing the The modern fields of cosmic-ray studies and experimental discharge. particle physics have much in common, as they both The last few years of the 19th century saw a burst investigate the high-energy interactions of subatomic of discoveries that not only cast light on the effect that particles. -

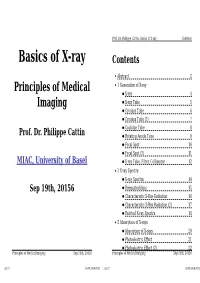

Basics of X-Ray Contents

Prof. Dr. Philippe Cattin: Basics of X-ray Contents Basics of X-ray Contents Abstract 2 Principles of Medical 1 Generation of X-ray X-ray 4 Imaging X-ray Tube 5 Crookes Tube 6 Crookes Tube (2) 7 Coolidge Tube 8 Prof. Dr. Philippe Cattin Rotating Anode Tube 9 Focal Spot 10 Focal Spot (2) 11 MIAC, University of Basel X-ray Tube, Filter, Collimator 12 2 X-ray Spectra X-ray Spectra 14 Sep 19th, 20156 Bremsstrahlung 15 Characteristic X-Ray Radiation 16 Characteristic X-Ray Radiation (2) 17 Emitted X-ray Spectra 18 3 Absorption of X-rays Absorption of X-rays 20 Photoelectric Effect 21 Photoelectric Effect (2) 22 Principles of Medical Imaging Sep 19th, 20156 Principles of Medical Imaging Sep 19th, 20156 1 of 27 26.09.2016 08:33 2 of 27 26.09.2016 08:33 Compton Effect 23 Prof. Dr. Philippe Cattin: Basics of X-ray Photoelectric vs. Compton Effect 24 4 Radiography Abstract (2) Radiography 26 Radiography Setup 27 Radiography Setup 28 5 Perils of X-rays "EDISON FEARS HIDDEN PERILS OF THE 30 X-RAYS" Principles of Medical Imaging Sep 19th, 20156 Principles of Medical Imaging Sep 19th, 20156 3 of 27 26.09.2016 08:33 4 of 27 26.09.2016 08:33 Generation of Prof. Dr. Philippe Cattin: Basics of X-ray Generation of X-ray X-ray X-ray Tube (5) The X-ray tube is a vacuum tube ( ). X-ray (4) The emitter (either a filament or a cathode) emits electrons → X-rays [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/X-ray] (or Röntgen rays) are The anode collects these Fig 1.2: Ancient X-ray tube Photons and thus part of the → electromagnetic spectrum electrons [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electromagnetic_radiation] with a The high voltage source wavelength in the range of , corresponding to connected to the cathode and frequencies in the range of . -

Lesson 37: Thomson's Plum Pudding Model

Lesson 37: Thomson's Plum Pudding Model Remember back in Lesson 18 when we looked at trapping moving particles in a circular path using a magnetic field? • In this lesson we look at how using this type of set up eventually helped physicists start to figure out the nature of the atom. Early Theories about Atoms In 1803 John Dalton presented his theory that the elements of the periodic table were made of atoms. • The main reason he was proposing this idea was to be able to explain the chemistry that he was studying. • Dalton believed that atoms were solid pieces of matter that could not be broken down any further. ◦ This is why his model is often referred to as the Solid Sphere Model. • Although Dalton's model was able to explain the way he saw chemical reactions working, he was unable to really prove that matter was made up of these atoms, or how chemical bonding could happen between them. During the late 1800's experiments with cathode ray tubes (CRTs) were starting to The negative give the first glimpses into what an atom might be. electrode is referred ● A cathode ray tube is just a vacuum tube with two electrodes at the ends. to as the cathode. That's the reason ○ When a really high voltage is applied, mysterious “cathode rays” this is called a moved from the negative electrode to the positive electrode. cathode ray tube. ○ Sometimes you could see a glow at the opposite end of the tube when the tube was turned on. ● William Crookes used a really high quality cathode ray tube in 1885. -

Röntgen's Discovery of X-Rays

Röntgen’s discovery of X-rays by Jean-Jacques Samueli1, PhD in physics Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen was born on 27 March 1845 in Lennep in Germany (Westphalia). He studied in Zurich and then became a professor of physics in Strasburg (1876–1879), which was then under German occupation. This was followed by posts in Giessen (1879–1888), Würzburg (1888–1900) and Geneva (1900–1920). He received the first Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901 for his discovery of X-rays, a discovery he had made in late 1895 using a Crookes tube in a darkened room. RÖNTGEN’S EXPERIMENT On 8 November 1895, Röntgen wrapped some black cardboard around a Crookes tube attached to a Ruhmkorff induction coil, in other words a step-up transformer excited by repeated electrical pulses. Every pulse produced an electric discharge in the low-pressure gas in the tube. After turning off the lights in the room, Röntgen noticed a fluorescent effect on a small paper screen painted with barium platinocyanide. One of the properties of barium platinocyanide is that it is fluorescent, which means it emits light when it is excited by photons. This fluorescence appeared when the paper was fewer than two metres away from the tube, even when the paper was obscured by black cardboard. Röntgen concluded that the tube was producing invisible radiation of an unknown nature, which he called an X-ray, and that this was causing the fluorescence he had observed. The Crookes tube Sir William Crookes (1832–1919) invented an experimental device, which is now known as a Crookes tube (or a discharge tube, gas-filled tube or cold cathode tube), to study the fluorescence of minerals. -

Radiation Safety Management for Crookes Tubes in Education Field

2021 / 06 / 19 The 6th International Symposium on Radiation Education Main Theme: Radiation Education and Radiation in Medical Science RadiationRadiation SafetySafety ManagementManagement forfor CrookesCrookes TubesTubes inin EducationEducation FieldField Osaka Prefecture University, Radiation Research Center, Masafumi Akiyoshi Special thanks: Crookes Tube Project Members in Japan [email protected] http://bigbird.riast.osakafu-u.ac.jp/~akiyoshi/Works/index.htm What is Crookes tube? Wilhelm Konrad Rontgen 1895, Found the X-ray during the experiment of discharge tube 1901, Got the first Nobel prize in physics William Crookes ③ ① At the cold cathode, cation in ① - ② - air is accelerated and knock - out secondary electrons. - - - Acceleration + of electron These electrons are accele ② -rated as the applied HV. Cathode Vacuum of + 0.005 - 0.1 Pa Accelerated electrons hit Anode ③ glass wall and radiate bremsstrahlung X-rays. 10-20kV HV from an induction coil How to Establish Safty Management for Crookes tube? Crookes tube has been used in junior-high science classes in Japan, and the primary purpose is to teach the characteristics of electrons and current, not for radiological education. Therefore, some teachers are not recognizing the radiation of X-ray from Crookes tube, and most of them have no information of the dose. However, it is possible to expose high dose of X-ray to students using a Crookes tube, where Hp(0.07) reaches 200mSv/h at a distance of 15cm. Some discharge tube that use hot cathode is Basic Plan operated with only several 100V, and even with cold cathode, some equipment can be operated By using low voltage type equipment, teachers at about 5kV. -

Back Matter (PDF)

[ 229 • ] INDEX TO THE PHILOSOPHICAL TRANSACTIONS, S e r ie s B, FOR THE YEAR 1897 (YOL. 189). B. Bower (F. 0.). Studies in the Morphology of Spore-producing Members.— III. Marattiaceae, 35. C Cheirostrobus, a new Type of Fossil Cone (Scott), 1. E. Enamel, Tubular, in Marsupials and other Animals (Tomes), 107. F. Fossil Plants from Palaeozoic Rocks (Scott), 1, 83. L. Lycopodiaceae; Spencerites, a new Genus of Cones from Coal-measures (Scott), 83. 230 INDEX. M. Marattiaceae, Fossil and Recent, Comparison of Sori of (Bower), 3 Marsupials, Tubular Enamel a Class Character of (Tomes), 107. N. Naqada Race, Variation and Correlation of Skeleton in (Warren), 135 P. Pteridophyta: Cheirostrobus, a Fossil Cone, &c. (Scott), 1. S. Scott (D. H.). On the Structure and Affinities of Fossil Plants from the Palaeozoic Ro ks.—On Cheirostrobus, a new Type of Fossil Cone from the Lower Carboniferous Strata (Calciferous Sandstone Series), 1. Scott (D. H.). On the Structure and Affinities of Fossil Plants from the Palaeozoic Rocks.—II. On Spencerites, a new Genus of Lycopodiaceous Cones from the Coal-measures, founded on the Lepidodendron Spenceri of Williamson, 83. Skeleton, Human, Variation and Correlation of Parts of (Warren), 135. Sorus of JDancea, Kaulfxissia, M arattia, Angiopteris (Bower), 35. Spencerites insignis (Will.) and S. majusculus, n. sp., Lycopodiaceous Cones from Coal-measures (Scott), 83. Sphenophylleae, Affinities with Cheirostrobus, a Fossil Cone (Scott), 1. Spore-producing Members, Morphology of.—III. Marattiaceae (Bower), 35. Stereum lvirsutum, Biology of; destruction of Wood by (Ward), 123. T. Tomes (Charles S.). On the Development of Marsupial and other Tubular Enamels, with Notes upon the Development of Enamels in general, 107. -

Tabea Cornel 1

Tabea Cornel 1 Betahistory The Historical Imagination of Neuroscience1 1. Introduction [T]he beta (β) of an investment is a measure of the risk arising from exposure to gen- eral market movements as opposed to idiosyncratic factors. The market portfolio of all investable assets has a beta of exactly 1. A beta below 1 can indicate either an in- vestment with lower volatility than the market, or a volatile investment whose price movements are not highly correlated with the market. … A beta above one generally means that the asset both is volatile and tends to move up and down with the mar- ket. … There are few fundamental investments with consistent and significant nega- tive betas, but some derivatives like equity put options can have large negative betas. (Wikipedia 2015) This paper inquires into how the history of neuroscience should be written. And it will not an- swer the question. Instead, it will draw together meta-histor(iograph)ical accounts and illustrate to what extent these could steer someone who aims at coming up with a qualified answer to this question in the right direction. Several old and not-so-old men have been wrestling with the problems of how history is or has been written and how it ought to be written. Before I embark on illustrations of different possible kinds of history-writing, previous work on which the elab- orations in this paper rest will be briefly introduced. Historian of medicine Roger Cooter published several reflections on the historiography of science and medicine, explicitly including neuroscience, over the course of the past years.