Rape Jokes Aren't Funny: the Mainstreaming of Rape Jokes In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FX's 'Legit', Jim Jefferies Embraced by Disabled Community

Follow Like 153k Subscribe Industry Tools Newsletters Daily PDF Register Log in Blocked Plug-in MAR -./$0123$2456782$95:;<5$8=5$&;>?7@6$.A$8=5 22 2 DAYS &73;B?5C$).<<D@78E 8:00 AM PDT 3/22/2013 by Aaron Couch SHARE (/pri 28 Comments (#comments) (3 (http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/node/430325#disqus_thread) )nt/4 0 Like 133303 (=5$:.<5CE23$:>5;8.>3$/.>>75C$783$C73;B?5C$:=;>;:85>3$<76=8 25) .AA5@C$F75/5>3G$BD8$A.D@C$8=.35$H.>8>;E;?3$=;F5$5;>@5C$8=5$3=./$3.<5$.A$783 A75>:538$A;@3I FX From left: Dan Bakkedahl, D.J. Qualls and Jim Jefferies in "Legit" Drugs, prostitution and masturbation are among the topics tackled by FX’s freshman comedy Legit. Despite those edgy plot points, it was the show’s multiple characters with disabilities that had co-creators Jim Jefferies and Peter O’Fallon worried they might offend viewers. From series regular Billy (DJ Qualls), a 30- !"#$%&'(!#$#%)!**%+&, something with muscular dystrophy, to Rodney (Nick Daley), a party hound with an intellectual disability, the world of Legit is full of characters trying to make it no matter their circumstances. 'Legit'(http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/live- Creators Spill Secrets of Theirfeed/legit-creators-spill-secrets-abrasive- Abrasive Yet Kind “We were kind of nervous,” Jefferies, the show’s star, Comedy tells The Hollywood Reporter (http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/live- (http://www.hollywoodreporter.com) . “We know we’re not feed/legit-creators-spill-secrets-abrasive- 417069) being nasty, but maybe people won’t see it the same way we see it.” STORY: 'Legit' Creators Spill Secrets of Their Abrasive Yet Kind Comedy Season(http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/live- Finale Scheduler: Your Guidefeed/2013-season-finale-schedule- to What Ends When (http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/live-feed/legit-creators-spill- 429839) (http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/live- secrets-abrasive-417069) feed/2013-season-finale-schedule-429839) But since premiering in January, it’s the characters with disabilities who have won the show some of its fiercest fans. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

Reflections on UK Comedy’s Glass Ceiling: Stand-Up Comedy and Contemporary Feminisms TOMSETT, Eleanor Louise Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/26442/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/26442/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Reflections on UK Comedy’s Glass Ceiling: Stand-up Comedy and Contemporary Feminisms Eleanor Louise Tomsett A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2019 Candidate declaration: I hereby declare that: 1. I have not been enrolled for another award of the University, or other academic or professional organisation, whilst undertaking my research degree. 2. None of the material contained in the thesis has been used in any other submission for an academic award. 3. I am aware of and understand the University's policy on plagiarism and certify that this thesis is my own work. The use of all published or other sources of material consulted have been properly and fully acKnowledged. 4. The worK undertaKen towards the thesis has been conducted in accordance with the SHU Principles of Integrity in Research and the SHU Research Ethics Policy. -

Racist Violence in the United Kingdom

RACIST VIOLENCE IN THE UNITED KINGDOM Human Rights Watch/Helsinki Human Rights Watch New York AAA Washington AAA London AAA Brussels Copyright 8 April 1997 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN 1-56432-202-5 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 96-77750 Addresses for Human Rights Watch 485 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10017-6104 Tel: (212) 972-8400, Fax: (212) 972-0905, E-mail: [email protected] 1522 K Street, N.W., #910, Washington, DC 20005-1202 Tel: (202) 371-6592, Fax: (202) 371-0124, E-mail: [email protected] 33 Islington High Street, N1 9LH London, UK Tel: (171) 713-1995, Fax: (171) 713-1800, E-mail: [email protected] 15 Rue Van Campenhout, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Tel: (2) 732-2009, Fax: (2) 732-0471, E-mail: [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org Gopher Address://gopher.humanrights.org:5000/11/int/hrw Listserv address: To subscribe to the list, send an e-mail message to [email protected] with Asubscribe hrw-news@ in the body of the message (leave the subject line blank). HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH Human Rights Watch conducts regular, systematic investigations of human rights abuses in some seventy countries around the world. Our reputation for timely, reliable disclosures has made us an essential source of information for those concerned with human rights. We address the human rights practices of governments of all political stripes, of all geopolitical alignments, and of all ethnic and religious persuasions. Human Rights Watch defends freedom of thought and expression, due process and equal protection of the law, and a vigorous civil society; we document and denounce murders, disappearances, torture, arbitrary imprisonment, discrimination, and other abuses of internationally recognized human rights. -

Cis Tv & Film Cv 2018-10

LANA VEENKER CSA & ERYN GOODMAN CSA SELECTED FILM CREDITS “Timmy Failure” Principal Casting (OR) Walt Disney Studios/Fayleure Prods | p. Jim Whitaker “Bad Samaritan” Principal Casting (OR) Electric Entertainment | d. Dean Devlin “Preserve” Principal Casting (OR) Preserve LLC/CineReach | d. Nicole Perlman “Wild” Principal Casting (OR) Fox Searchlight/Pacific Standard | d. Jean-Marc Vallée “Gone” Principal Casting (OR) Lakeshore Entertainment | d. Heitor Dhalia “Twilight” Principal Casting (OR & WA) Summit Entertainment | d. Catherine Hardwicke “Paranoid Park” Principal Casting MK2/Tsetse Fly Film Co. | d. Gus Van Sant “The Burning Plain” Principal Casting (OR) 2929 Productions | d. Guillermo Arriaga “Management” Principal Casting (OR) Sidney Kimmel Entertainment | d. Stephen Belber “The Heretic” Principal Casting (OR) Havoc Films | d. Tim Robbins “Chacun Son Cinéma: First Kiss” Principal Casting ARTE/Canal+/Elzevir | d. Gus Van Sant “Feast of Love” Principal Casting (OR & WA) Lakeshore Entertainment | d. Robert Benton “Into the Wild” Additional Casting (OR) Paramount Vantage | d. Sean Penn SELECTED TV CREDITS Trinkets (S1) Principal Casting (NW) Netflix/Awesomeness TV | e.p. Linda Gase American Vandal (S2) Principal Casting (NW) Netflix/CBS Studios/Funny or Die | d. Tony Yacenda Pretty Little Liars: The Perfectionists (S1) Principal Casting (NW) Warner Horizon/Freeform | d. Marlene King Staties (Pilot) Principal Casting (NW) ABC Studios/Maniac Productions | d. Rob Bowman Angie Tribeca (1 episode) Principal Casting (OR) TBS/Carousel Prods | e.p. Nancy Carell & Steve Carell “Here and Now” (S1) Principal Casting (OR) HBO/Perplexed Production Services | e.p. Alan Ball “The Show” (Pilot) Series Regulars (US Search) BLACKPILLS/Together Media/Vice | e.p. Luc Besson The Wonderland Murders (S1) Principal Casting (OR) American Chainsaws Ent./Baltic Tiger | d. -

BOB DOBSON – LANCASHIRE LISTS ‘Acorns’ 3 Staining Rise Staining Blackpool FY3 0BU Tel 01253 886103 Email: [email protected]

BOB DOBSON – LANCASHIRE LISTS ‘Acorns’ 3 Staining Rise Staining Blackpool FY3 0BU Tel 01253 886103 Email: [email protected] A CATALOGUE of SECONDHAND LANCASHIRE BOOKS FOR ORDERING PURPOSES PLEASE REFER TO THIS . CATALOGUE AS ‘LJ’ (Updated on 9. 11. 2020) All books in this catalogue are in good secondhand condition with major faults stated and minor ones ignored. Any book found to be poorer than described may be returned at my expense. My integrity is your guarantee. All secondhand items are sent ‘on approval’ to ensure the customer’s satisfaction before payment is made. Postage on these is extra to the stated price, so please do not send payment with order for these secondhand books I( want you to be satisfied with them before paying..Postage will not exceed £5 to a UK address. Pay by cheque or bank transfer. I do not accept card payments. I am preparing to ‘sell up’,and to this end, I offer at least 30% off the stated price to those who will call to see my stock. To those wanting books to be posted, I make the same offer if the order without that reduction comes to £40. Postage to a UK address will still be capped @ £5 If you prefer not to receive any future issues of this catalogue, please inform me so that I can delete your name from my mailing list A few abbreviations have been used :- PENB Published Essay Newly Bound – an essay taken from a learned journal , newly bound in library cloth dw dustwrapper, or dustjacket (nd) date of publication not known. -

COMEDIAN JIM JEFFERIES ANNOUNCES the MOIST TOUR WHICH COMES to the FLORIDA THEATRE on OCTOBER 10, 2021 Tickets on Sale Beginning Friday, June 4 at 12:00 P.M

COMEDIAN JIM JEFFERIES ANNOUNCES THE MOIST TOUR WHICH COMES TO THE FLORIDA THEATRE ON OCTOBER 10, 2021 Tickets On Sale Beginning Friday, June 4 at 12:00 p.m. Jacksonville, Fla. (June 1, 2021) – Jim Jefferies (Legit, FX; The Jim Jefferies Show, Comedy Central) announced today his new The Moist Tour which kicks off September 23 in New York City. Tickets go on sale to the general public beginning Friday, June 4 at 12:00 p.m. with a fan presale beginning Wednesday, June 2 at 10:00 a.m. For more information and tickets, visit jimjefferies.com. This Sydney native is one of the most popular and respected comedians of his generation, entertaining audiences across the globe with his provocative, belief-challenging, and thought-provoking comedy. Jim was honored as Stand-Up Comedian of the Year at the Just for Laughs Festival in summer 2019. At the end of 2019, he started his Oblivious Tour and toured all around Europe and North America. Jim’s ninth stand up special Intolerant came out on Netflix last year. He currently hosts his own podcast I Don’t Know About That with Jim Jefferies and releases new episodes on Tuesdays with video available on Jim's YouTube channel and audio available everywhere you get podcasts. JIM JEFFERIES: THE MOIST TOUR Friday, July 30, 2021 Las Vegas Nevada The Mirage (on sale now) Saturday, July 31, 2021 Las Vegas Nevada The Mirage (on sale now) Thursday, September 23, 2021 New York, New York Beacon Theatre Saturday, September 25, 2021 Chicago, Illinois Chicago Theatre Sunday, September 26, 2021 Indianapolis, Indiana Clowes Memorial Hall (on sale June 11) Friday, October 8, 2021 Fort Myers, Florida Barbara B. -

Eric Andre Returning to Tour Australia & New Zealand in May 2017 After Selling out His Debut Run of Shows!

ERIC ANDRE RETURNING TO TOUR AUSTRALIA & NEW ZEALAND IN MAY 2017 AFTER SELLING OUT HIS DEBUT RUN OF SHOWS! Currently in Australia for his sold-out run of debut shows, Frontier Comedy are thrilled to announce that Eric Andre will return to our shores in May 2017 for his biggest Australian shows to date and first ever Auckland shows. Fans Down Under cannot get enough of Eric; his debut tour sold out in just days with an extra Sydney show added to meet massive demand and record-breaking attendances in Melbourne. Both Comic’s Lounge shows saw Eric pull the biggest crowds the venue had ever seen - breaking the attendance record previously held by Jim Jefferies in 2012 - with audiences treated to a special surprise appearance from The Eric Andre Show co-host Hannibal Buress. ★★★★½ ‘Anyone looking for a night of chaotic and disorderly comedy need look no further. Andre has every surprise up his sleeve and then some when it comes to the ultimate showing of weird and wonderful.’ - The Music ‘One of the most off-kilter and versatile comedians on planet earth.’ - VICE Boundary-pushing comedian and the world’s most unstable talk show host Eric Andre has been perplexing and provoking audiences with late night cult hit The Eric Andre Show since 2012, where he’s made Tyler The Creator cry, exposed himself to Seth Rogen, and covered Ariel Pink in toilet water. But he's been bringing the laughs long before then with his daring and inventive approach to stand-up. Every bit as uproarious as he is bizarre, Andre's unyielding enthusiasm, infectious energy and surrealist humour have him consistently selling out venues across the US and Canada. -

British Comedy, Global Resistance: Russell Brand, Charlie Brooker

British Comedy, Global Resistance: Russell Brand, Charlie Brooker, and Stewart Lee (Forthcoming European Journal of International Relations) Dr James Brassett Introduction: Satirical Market Subjects? An interesting facet of the austerity period in mainstream British politics has been the rise (or return) to prominence of an apparently radical set of satirists.1 Comedians like Russell Brand, Charlie Brooker and Stewart Lee have consolidated already strong careers with a new tranche of material that meets a widespread public mood of disdain for the failure and excess of ‘global capitalism’. This can be seen through Brand’s use of tropes of revolution in his Messiah Complex and Paxman Interview, Brooker’s various subversions of the media-commodity nexus in Screenwipe, and Lee’s regular Guardian commentaries on the instrumentalisation of the arts and social critique. While radical comedy is by no means new, it has previously been associated with a punk/socialist fringe, whereas the current batch seems to occupy a place within the acceptable mainstream of British society: BBC programs, Guardian columns, sell out tours, etc. Perhaps a telling indication of the ascendancy of these ‘radical’ comedians has been the growing incidence of broadsheet articles and academic blogs designed to ‘clip their wings’. For example, Matt Flinders has argued that Russell Brand’s move to ‘serious politics’ is undermined by a general decline in the moral power of satire: 1 Numerous people have read and commented on this paper. In particular, I thank Erzsebet Strausz, Lisa Tilley, Madeleine Fagan, Kyle Grayson, Roland Bleiker and Nick Vaughan-Williams. The idea for the paper arose in a series of enjoyable discussions with Alex Sutton and Juanita Elias and I am grateful for their encouragement to develop these ideas. -

The Performance of Place and Comedy Explored Through Postdramatic and Popular Forms with Reference to the Staging of 'A Good Neet Aht'

THE PERFORMANCE OF PLACE AND COMEDY EXPLORED THROUGH POSTDRAMATIC AND POPULAR FORMS WITH REFERENCE TO THE STAGING OF 'A GOOD NEET AHT' Philip Green University of Salford School of Arts and Media Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (PhD) 2020 Table of contents i List of tables vi List if images and photographs vii Acknowledgements viii Abstract ix Curtain up: The journey begins 1 1. Beginnings: mapping out the journey 2 1.1 Aims and objectives 2 1.2 Autoethnography 3 1.3 Place 5 1.4 Performance: the postdramatic and the popular 7 1.4.1 Postdramatic 8 1.4.1.1 A contested landscape 8 1.4.1.2 Panorama of the postdramatic 8 1.4.2 Popular performance 9 1.5 Structure 11 1.5.1 Chapter 2: Planning the journey’s route: Methodology 11 1.5.2 Chapter 3: Surveying the landscape for the journey ahead: place, class, performance 11 1.5.3 Chapter 4: The journey into performance: key concepts in the analysis of performing place and comedy 12 1.5.4 Chapter 5: An audience of travelling companions: The iterations of A Good Neet Aht and audience response 12 1.5.5 Chapter 6: Arrivals and Departures: Conclusion 12 1.6 Gaps in knowledge and original contribution 13 1.6.1 Northern stereotypes and stand-up comedy 13 1.6.2 Original contribution 13 Entr’acte 1: 1, Clifton Road, Sharlston 14 2. Planning the journey’s route: Methodology 15 2.1 Autoethnography 15 2.1.1 Autoethnography and place 15 2.1.2 Performative-I 16 2.1.3 Performative-I persona and dialogical performance 17 2.2 Geographical space in the studio and the reading of maps 18 2.3 Popular performance and the comic-I 22 2.3.1 Reading stand-up 23 i 2.3.1.1 Kowzan and analysis of the ‘mother in law and the shark’ 27 2.3.1.2 Pavis and ‘blowing raspberries’ 28 2.4 Destinations: Iterations of A Good Neet Aht 32 Entr’acte 2: 36, Clifton Road, Sharlston 35 3. -

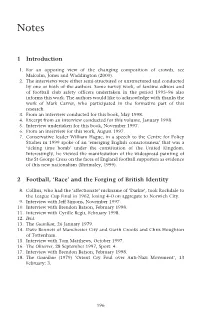

1 Introduction 2 Football, 'Race' and the Forging of British Identity

Notes 1 Introduction 1. For an opposing view of the changing composition of crowds, see Malcolm, Jones and Waddington (2000). 2. The interviews were either semi-structured or unstructured and conducted by one or both of the authors. Some survey work, of fanzine editors and of football club safety officers undertaken in the period 1995–96 also informs this work. The authors would like to acknowledge with thanks the work of Mark Carver, who participated in the formative part of this research. 3. From an interview conducted for this book, May 1998. 4. Excerpt from an interview conducted for this volume, January 1998. 5. Interview undertaken for this book, November 1997. 6. From an interview for this work, August 1997. 7. Conservative leader William Hague, in a speech to the Centre for Policy Studies in 1999 spoke of an ‘emerging English consciousness’ that was a ‘ticking time bomb’ under the constitution of the United Kingdom. Interestingly, he viewed the manifestation of the widespread painting of the St George Cross on the faces of England football supporters as evidence of this new nationalism (Shrimsley, 1999). 2 Football, ‘Race’ and the Forging of British Identity 8. Collins, who had the ‘affectionate’ nickname of ‘Darkie’, took Rochdale to the League Cup Final in 1962, losing 4–0 on aggregate to Norwich City. 9. Interview with Jeff Simons, November 1997. 10. Interview with Brendon Batson, February 1998. 11. Interview with Cyrille Regis, February 1998. 12. Ibid. 13. The Guardian, 26 January 1979. 14. Dave Bennett of Manchester City and Garth Crooks and Chris Houghton of Tottenham. -

British Cult Comedy.Indb 215 16/8/06 12:34:16 Pm Cult Comedy Club up the Creek in Greenwich, Southeast London

Geography Lessons: comedy around Britain British Cult Comedy.indb 215 16/8/06 12:34:16 pm Cult comedy club Up The Creek in Greenwich, southeast London British Cult Comedy.indb 216 16/8/06 12:34:17 pm Geography Lessons: comedy around Britain Comedy just wouldn’t be comedy without local roots. And that is why, in this chapter, we take you on a tour of British comedy from Cornwall to the Scottish Highlands, visiting local comedic landmarks, clubs and festivals. Comedy is prey to the same homogenizing forces Do Part, was successfully re-created in America, that have made Starbucks globally ubiquitous but Germany and Israel, suggesting that comedy that humour doesn’t travel so easily or predictably as touches, however lightly, on universal truths can cappuccino. In the past, slang, regional vocabu- be exported around the world. lary, accents and local knowledge have often A comic’s roots, cherished or spurned, are limited a comic’s appeal, explaining why such crucial to their humour. The small screen has acts as George Formby and Tommy Trinder never made it easier for contemporary acts – nota- quite transcended the north/south divide. Yet a bly Johnny Vegas, Peter Kay and Ben Elton character as localized as Alf Garnett, the charis- – to achieve national recognition while retain- matic Cockney bigot in the sitcom Till Death Us ing a regional identity. Since the 1980s, a more 217 British Cult Comedy.indb 217 16/8/06 12:34:17 pm GEOGRapHY LESSONS: COmedY arOUND brItaIN adventurous approach to sitcoms has meant that theme to British comedy, it was that, as Linda shows such as The Royle Family have had a much Smith told him: “A lot of comics come from more authentic local flavour than most of their the edge of nowhere.” Smith often argued with predecessors.