British Comedy, Global Resistance: Russell Brand, Charlie Brooker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celebrities As Political Representatives: Explaining the Exchangeability of Celebrity Capital in the Political Field

Celebrities as Political Representatives: Explaining the Exchangeability of Celebrity Capital in the Political Field Ellen Watts Royal Holloway, University of London Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Politics 2018 Declaration I, Ellen Watts, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Ellen Watts September 17, 2018. 2 Abstract The ability of celebrities to become influential political actors is evident (Marsh et al., 2010; Street 2004; 2012, West and Orman, 2003; Wheeler, 2013); the process enabling this is not. While Driessens’ (2013) concept of celebrity capital provides a starting point, it remains unclear how celebrity capital is exchanged for political capital. Returning to Street’s (2004) argument that celebrities claim to speak for others provides an opportunity to address this. In this thesis I argue successful exchange is contingent on acceptance of such claims, and contribute an original model for understanding this process. I explore the implicit interconnections between Saward’s (2010) theory of representative claims, and Bourdieu’s (1991) work on political capital and the political field. On this basis, I argue celebrity capital has greater explanatory power in political contexts when fused with Saward’s theory of representative claims. Three qualitative case studies provide demonstrations of this process at work. Contributing to work on how celebrities are evaluated within political and cultural hierarchies (Inthorn and Street, 2011; Marshall, 2014; Mendick et al., 2018; Ribke, 2015; Skeggs and Wood, 2011), I ask which key factors influence this process. -

(Dis)Believing and Belonging: Investigating the Narratives of Young British Atheists1

(Dis)Believing and Belonging: Investigating the Narratives of Young British Atheists1 REBECCA CATTO Coventry University JANET ECCLES Independent Researcher Abstract The development and public prominence of the ‘New Atheism’ in the West, particularly the UK and USA, since the millennium has occasioned considerable growth in the study of ‘non-religion and secularity’. Such work is uncovering the variety and complexity of associated categories, different public figures, arguments and organi- zations involved. There has been a concomitant increase in research on youth and religion. As yet, however, little is known about young people who self-identify as atheist, though the statistics indicate that in Britain they are the cohort most likely to select ‘No religion’ in surveys. This article addresses this gap with presentation of data gathered with young British people who describe themselves as atheists. Atheism is a multifaceted identity for these young people developed over time and through experience. Disbelief in God and other non-empirical propositions such as in an afterlife and the efficacy of homeopathy and belief in progress through science, equality and freedom are central to their narratives. Hence belief is taken as central to the sociological study of atheism, but understood as formed and performed in relationships in which emotions play a key role. In the late modern context of contemporary Britain, these young people are far from amoral individualists. We employ current theorizing about the sacred to help understand respondents’ belief and value-oriented non-religious identities in context. Keywords: Atheism, Youth, UK, Belief, Sacred Phil Zuckerman (2010b, vii) notes that for decades British sociologist Colin Campbell’s call for a widespread analysis of irreligion went largely un- heeded (Campbell 1971). -

Treloar's Student Is Bbc Two Tv Star

Kindly sponsored by TRELOAR’S STUDENT IS BBC TWO TV STAR Inside this Issue • Don’t Forget The Driver • Woodlarks visit • National Open Youth Orchestra • September 2019 A visit from our Royal Patron, HRH The Countess of Wessex GCVO • Nina’s Story • Sophie’s gift for Rory Bremner Image courtesy of BBC/Sister Pictures 1 About Treloar’s Founded in 1907, Treloar’s is a School and College for children and young adults aged 2-25 with physical disabilities. Every year we have to raise over £2 million to provide all our students with access to the specialist staff, equipment and opportunities needed to give them the confidence and skills to realise their full potential. With your support, we can help all our young people enjoy the chance to achieve so much more than they, or their parents, could ever have imagined possible. Thank you. Autumn edition of Treloar’s Today A warm welcome to you, in my first edition of Treloar’s Today. I would like to thank Homes Estate Agents for continuing to sponsor Treloar’s Today – we are very grateful for your generous support. Since joining earlier this year I have enjoyed the most amazing welcome from students, parents, colleagues, governors, trustees and supporters alike. I would also like to make a special l l mention to Tony Reid, for his insight and support passing over the leadership of the Trust i to me and to our Principal, Martin Ingram, for his warm welcome and sharing of knowledge. W d n a Ou sica As we refine our new strategy the Trust is focused on remaining true to Sir William’s r CEO Jes original aims and ever cognisant of the evolving needs of young people with disabilities and the changing nature of those disabilities. -

TRINITY COLLEGE Cambridge Trinity College Cambridge College Trinity Annual Record Annual

2016 TRINITY COLLEGE cambridge trinity college cambridge annual record annual record 2016 Trinity College Cambridge Annual Record 2015–2016 Trinity College Cambridge CB2 1TQ Telephone: 01223 338400 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.trin.cam.ac.uk Contents 5 Editorial 11 Commemoration 12 Chapel Address 15 The Health of the College 18 The Master’s Response on Behalf of the College 25 Alumni Relations & Development 26 Alumni Relations and Associations 37 Dining Privileges 38 Annual Gatherings 39 Alumni Achievements CONTENTS 44 Donations to the College Library 47 College Activities 48 First & Third Trinity Boat Club 53 Field Clubs 71 Students’ Union and Societies 80 College Choir 83 Features 84 Hermes 86 Inside a Pirate’s Cookbook 93 “… Through a Glass Darkly…” 102 Robert Smith, John Harrison, and a College Clock 109 ‘We need to talk about Erskine’ 117 My time as advisor to the BBC’s War and Peace TRINITY ANNUAL RECORD 2016 | 3 123 Fellows, Staff, and Students 124 The Master and Fellows 139 Appointments and Distinctions 141 In Memoriam 155 A Ninetieth Birthday Speech 158 An Eightieth Birthday Speech 167 College Notes 181 The Register 182 In Memoriam 186 Addresses wanted CONTENTS TRINITY ANNUAL RECORD 2016 | 4 Editorial It is with some trepidation that I step into Boyd Hilton’s shoes and take on the editorship of this journal. He managed the transition to ‘glossy’ with flair and panache. As historian of the College and sometime holder of many of its working offices, he also brought a knowledge of its past and an understanding of its mysteries that I am unable to match. -

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

Reflections on UK Comedy’s Glass Ceiling: Stand-Up Comedy and Contemporary Feminisms TOMSETT, Eleanor Louise Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/26442/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/26442/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Reflections on UK Comedy’s Glass Ceiling: Stand-up Comedy and Contemporary Feminisms Eleanor Louise Tomsett A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2019 Candidate declaration: I hereby declare that: 1. I have not been enrolled for another award of the University, or other academic or professional organisation, whilst undertaking my research degree. 2. None of the material contained in the thesis has been used in any other submission for an academic award. 3. I am aware of and understand the University's policy on plagiarism and certify that this thesis is my own work. The use of all published or other sources of material consulted have been properly and fully acKnowledged. 4. The worK undertaKen towards the thesis has been conducted in accordance with the SHU Principles of Integrity in Research and the SHU Research Ethics Policy. -

Racist Violence in the United Kingdom

RACIST VIOLENCE IN THE UNITED KINGDOM Human Rights Watch/Helsinki Human Rights Watch New York AAA Washington AAA London AAA Brussels Copyright 8 April 1997 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN 1-56432-202-5 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 96-77750 Addresses for Human Rights Watch 485 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10017-6104 Tel: (212) 972-8400, Fax: (212) 972-0905, E-mail: [email protected] 1522 K Street, N.W., #910, Washington, DC 20005-1202 Tel: (202) 371-6592, Fax: (202) 371-0124, E-mail: [email protected] 33 Islington High Street, N1 9LH London, UK Tel: (171) 713-1995, Fax: (171) 713-1800, E-mail: [email protected] 15 Rue Van Campenhout, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Tel: (2) 732-2009, Fax: (2) 732-0471, E-mail: [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org Gopher Address://gopher.humanrights.org:5000/11/int/hrw Listserv address: To subscribe to the list, send an e-mail message to [email protected] with Asubscribe hrw-news@ in the body of the message (leave the subject line blank). HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH Human Rights Watch conducts regular, systematic investigations of human rights abuses in some seventy countries around the world. Our reputation for timely, reliable disclosures has made us an essential source of information for those concerned with human rights. We address the human rights practices of governments of all political stripes, of all geopolitical alignments, and of all ethnic and religious persuasions. Human Rights Watch defends freedom of thought and expression, due process and equal protection of the law, and a vigorous civil society; we document and denounce murders, disappearances, torture, arbitrary imprisonment, discrimination, and other abuses of internationally recognized human rights. -

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 15 – 21 May 2021 Page 1 of 10 SATURDAY 15 MAY 2021 Producer: Jill Waters Comedy Chat Show About Shame and Guilt

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 15 – 21 May 2021 Page 1 of 10 SATURDAY 15 MAY 2021 Producer: Jill Waters comedy chat show about shame and guilt. First broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in June 1998. Each week Stephen invites a different eminent guest into his SAT 00:00 Planet B (b00j0hqr) SAT 03:00 Mrs Henry Wood - East Lynne (m0006ljw) virtual confessional box to make three 'confessions' are made to Series 1 5. The Yearning of a Broken Heart him. This is a cue for some remarkable storytelling, and 5. The Smart Money No sooner has Lady Isabel been betrayed by the wicked Francis surprising insights. John and Medley are transported to a world of orgies and Levison than she is left unrecognisably disfigured by a terrible We’re used to hearing celebrity interviews where stars are circuses, where the slaves seek a new leader. train crash. persuaded to show off about their achievements and talk about Ten-part series about a mystery virtual world. What is to become of her? their proudest moments. Stephen isn't interested in that. He Written by Paul May. Mrs Henry Wood's novel dramatised by Michael Bakewell. doesn’t want to know what his guests are proud of, he wants to John ...... Gunnar Cauthery Mrs Henry Wood ... Rosemary Leach know what makes them ashamed. That’s surely the way to find Lioba ...... Donnla Hughes Lady Isabel ... Moir Leslie out what really makes a person tick. Stephen and his guest Medley ...... Lizzy Watts Mr Carlyle ... David Collings reflect with empathy and humour on things like why we get Cerberus ..... -

2014 BAFTA TV Awards Full List of Nominations

NOMINATIONS IN 2014 LEADING ACTOR JAMIE DORNAN The Fall – BBC Two SEAN HARRIS Southcliffe – Channel 4 LUKE NEWBERRY In The Flesh – BBC Three DOMINIC WEST Burton and Taylor – BBC Four LEADING ACTRESS HELENA BONHAM CARTER Burton and Taylor – BBC Four OLIVIA COLMAN Broadchurch - ITV KERRIE HAYES The Mill – Channel 4 MAXINE PEAKE The Village – BBC One SUPPORTING ACTOR DAVID BRADLEY Broadchurch – ITV JEROME FLYNN Ripper Street – BBC One NICO MIRALLEGRO The Village – BBC One RORY KINNEAR Southcliffe – Channel 4 SUPPORTING ACTRESS SHIRLEY HENDERSON Southcliffe – Channel 4 SARAH LANCASHIRE Last Tango in Halifax – BBC One CLAIRE RUSHBROOK My Mad Fat Diary – E4 NICOLA WALKER Last Tango in Halifax – BBC One ENTERTAINMENT PERFORMANCE ANT AND DEC Ant and Dec’s Saturday Night Takeaway – ITV CHARLIE BROOKER 10 O’Clock Live – Channel 4 SARAH MILLICAN The Sarah Millican Television Programme – BBC Two GRAHAM NORTON The Graham Norton Show – BBC One FEMALE PERFORMANCE IN A COMEDY PROGRAMME FRANCES DE LA TOUR Vicious – ITV KERRY HOWARD Him & Her: The Wedding – BBC Three DOON MACKICHAN Plebs – ITV2 KATHERINE PARKINSON The IT Crowd – Channel 4 MALE PERFORMANCE IN A COMEDY PROGRAMME RICHARD AYOADE The IT Crowd – Channel 4 MATHEW BAYNTON The Wrong Mans – BBC Two JAMES CORDEN The Wrong Mans – BBC Two CHRIS O’DOWD The IT Crowd – Channel 4 Arqiva British Academy Television Awards – Nominations Page 1 SINGLE DRAMA AN ADVENTURE IN SPACE AND TIME Mark Gatiss, Matt Strevens, Terry McDonough, Caroline Skinner – BBC Wales/BBC America/BBC Two BLACK MIRROR: BE RIGHT BACK -

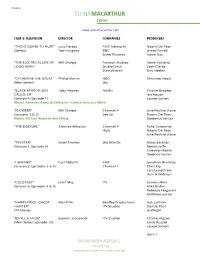

SELINA MACARTHUR Editor

(7/20/21) SELINA MACARTHUR Editor www.selinamacarthur.com FILM & TELEVISION DIRECTOR COMPANIES PRODUCERS “THIS IS GOING TO HURT” Lucy Forbes AMC Networks Naomi De Pear (Series) Tom Kingsley BBC James Farrell Sister Pictures Adam Kay “THE ELECTRICAL LIFE OF Will Sharpe Amazon Studios Adam Ackland LOUIS WAIN” StudioCanal Leah Clarke SunnyMarch Guy Heeley “CATHERINE THE GREAT” Phillip Martin HBO Christine Healy (Mini-Series) Sky “BLACK MIRROR: USS Toby Haynes Netflix Charlie Brooker CALLISTER” Ian Hogan (Season 4, Episode 1) Louise Sutton Winner: Primetime Emmy for Editing for a Limited Series or a Movie “FLOWERS” Will Sharpe Channel 4 Jane Featherstone (Seasons 1 & 2) See So Naomi De Pear Winner: RTS Craft Award for Best Editing Diederick Santer “THE BISEXUAL” Desiree Akhavan Channel 4 Katie Carpenter Hulu Naomi De Pear Jane Featherstone “TIN STAR” Grant Harvey Sky Atlantic Alison Jackson (Season 1, Episode 6) Rowan Joffe Cameron Roach Diedrick Santer “HUMANS” Carl Tibbetts AMC Jonathan Brackley (Season 2, Episodes 3 & 4) Channel 4 Chris Fry Lars Lundström Henrik Widman “COLD FEET” Juliet May ITV Kenton Allen (Season 6, Episodes 3 & 4) Mike Bullen Rebecca Ferguson Matthew Justice “HARRY PRICE: GHOST Alex Pillai Bentley Productions Jack Lothian HUNTER” ITV Studios Denise Paul (TV Movie) Jo Wright “JEKYLL & HYDE” Stewart Svaasand ITV Studios Charlie Higson (Mini-Series, Episode 10) Emily Russell Louise Sutton (cont.) SANDRA MARSH & ASSOCIATES +1 (310) 285-0303 [email protected] • www.sandramarsh.com (7/20/21) SELINA MACARTHUR Editor - 2 -

Building the Big Society

Building the Big Society Defining the Big Society Delivering the Big Society Financing the Big Society Can big ideas succeed in politics? With Clive Barton, Roberta Blackman-Woods MP, Rob Brown, Sir Stephen Bubb, Patrick Butler, Chris Cummings, Michele Giddens, David Hutchison, Bernard Jenkin MP, Rt Hon Oliver Letwin MP, Jesse Norman MP, Ali Parsa, Michael Smyth CBE, Matthew Taylor and Andrew Wates Clifford Chance 10 Upper Bank Street London E14 5JJ Thursday 31 March 2011 Reform is an independent, non-party think tank whose mission is to set out a better way to deliver public services and economic prosperity. We believe that by reforming the public sector, increasing investment and extending choice, high quality services can be made available for everyone. Our vision is of a Britain with 21st Century healthcare, high standards in schools, a modern and efficient transport system, safe streets, and a free, dynamic and competitive economy. Reform 45 Great Peter Street London SW1P 3LT T 020 7799 6699 [email protected] www.reform.co.uk Building the Big Society / Reform Contents Building the Big Society Introduction 2 Pamphlet articles 5 Full transcript 14 www.reform.co.uk 1 Building the Big Society / Reform Introduction Nick Seddon, Deputy Director, Reform The Big Society is this Government’s Big “lacking a cutting edge” and “has no Sir Stephen Bubb spoke in favour of this Idea. Part philosophy, part practical teeth”. Others are outright hostile. They feature of the Government’s public service programme, it is the glue that holds see it as a cover for cuts. -

BB Fou St S BB CT Ur Ser BC O Thr Rvi on Ree Ce Ne, Ea BB Nd BC

BBC Trust service review: BBC OnOne, BBC Two, BBC Three and BBC Fouru Consultation Questions November 2013 Getting the best out of the BBC for licence fee payers Introduction to the consultation Background The BBC Trust works on behalf of licence fee payers to ensure that the BBC provides high quality services and good value for everyone in the UK. One of the ways we do this is by carrying out an in-depth review of each of the BBC's services at least once every five years. This consultation is part of our review of BBC television. It will help us to get the views of licence fee payers on BBC One, BBC Two, BBC Three and BBC Four. What do you think are the strength of the channels and what should the BBC do to make these television services better? How to take part in the consultation The simplest way to take part in the consultation is by completing the questionnaire online at www.bbc.co.uk/bbctrust/have_your_say/ If you cannot reply online, you can return it to us using the enclosed pre-paid envelope at BBC Trust, Television Services Consultation, 180 Great Portland Street, London W1W 5QZ. To request a questionnaire in audio or braille please call 0800 0680 116 or Textphone 0800 0153 350. The consultation is open until 14th Feb 2014, we are unable to accept responses after this date. You can answer as many or as few questions as you wish. What happens next? Once the consultation closes, we will analyse the responses, alongside a range of other information that we are collecting as part of this review. -

A Conversation About King Rocker Between the Quietus, Stewart Lee, Michael Cumming and Robert Lloyd

No Image: A conversation about King Rocker between the Quietus, Stewart Lee, Michael Cumming and Robert Lloyd. It looks like a music documentary. Look, there’s a famous person [Stewart Lee] walking out of a train station telling viewers where they are and why it’s important. Now they’re telling us what is going on and why we’re here. It feels like a music documentary. And King Rocker, Michael Cumming and Stewart Lee’s film about Robert Lloyd and The Nightingales is one. It’s also not. You’d expect a film by the director of Brass Eye and Toast of London, and the comedian behind some of the most brilliant stand-up ever to come from these shores to be funny and smart but the experience of King Rocker explodes those expectations. It’s not hyperbole to say this is one of the best music documentaries of all time. Hilarious and brilliantly knowing about the form of music documentaries and caustic about the music industry and fame, at its moving heart it’s a wonderful homage to and portrait of a true outsider artist and inspiring comeback story that in the already boiling maelstrom of 2021 feels profoundly necessary. The film follows Stewart Lee and Robert Lloyd as they talk about Lloyd’s life as front-man and creative driver of post-punk favourites The Prefects and latterly The Nightingales. Through a series of funny and insightful conversations as they hunt down a famous 1970s public art sculpture of King Kong that is central to both men’s stories, the pair and assorted friends, acolytes and naysayers including the rest of the band and family members plus Frank Skinner, John Taylor (yep, of Duran Duran), Nigel Slater (!) and Robin Askwith (!!) discuss the past, the ups, the downs and the hazy memories of it all.