Disturbance and Feeding Shorebirds on the Exe Estuary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sediment Yields in the Exe Basin: a Longer-Term Perspective

Sediment Dynamics and the Hydromorphology of Fluvial Systems (Proceedings of a symposium held in 12 Dundee, UK, July 2006). IAHS Publ. 306, 2006. Sediment yields in the Exe Basin: a longer-term perspective ANNA HARLOW, BRUCE WEBB & DES WALLING School of Geography, Archaeology and Earth Resources, Department of Geography, Amory Building, Rennes Drive, Exeter EX4 4RJ, UK [email protected] Abstract In the UK, fine sediment is viewed increasingly as a diffuse pollu- tant due to its role as a vector for the transport of potential contaminants, and in causing siltation, which may have adverse effects on river and estuarine habitats. There is a need, therefore, for river managers to have reliable information on sediment budgets in order to plan measures that will achieve “good” status under the EU Water Framework Directive. As part of a wider sediment-budget investigation in the EU-funded Cycleau Project, detailed records of fine sediment yield over the 10-year period from 1994–2003 have been analysed for the Exe Basin (1500 km2), a principal river system of southwest England. The longer-term average yields in the three major tributaries of the Exe Basin are discussed and results of monitoring of sediment loads at a site near the tidal limit over a one-year period confirm the importance of the River Exe in contributing sediment to the Estuary. Key words diffuse pollution; Exe Basin and estuary; longer-term behaviour; suspended sediment yields INTRODUCTION River systems provide a key pathway along which fine sediment (silt and clay particles of <63 µm in diameter) is transferred from the terrestrial to the estuarine environment. -

A CASE STUDY Paul Canning1 the Exe Estuary Is

DETERMINING A SUSTAINABLE APPROACH TO MANAGING AN ESTUARY MOUTH – A CASE STUDY Paul Canning1 Estuaries and their floodplains represent locations where significant population, industry and environmental interests exist. Sand spits located at estuary mouths are one factor in influencing both hydrodynamics and geomorphology. As such, their management is important as regards managing both flood and coastal risk, and the evolution of designated flora and fauna. This paper describes a study to develop a way forward for managing Dawlish Warren sand spit, located at the mouth of the Exe Estuary in Devon, UK. Dawlish Warren sand spit is important as it influences geomorphological evolution of the mouth and wider estuary, provides storm sheltering for up to 2,900 properties and national transport infrastructure in the estuary, is an internationally designated Special Area of Conservation (SAC), and influences the wider Exe Estuary Special Protection Area (SPA). Keywords: climate change, adaptation, sustainable, estuaries OVERVIEW OF EXISTING SITUATION The Exe Estuary is located in Devon, UK (see Figure 1). It is a spit enclosed drowned river valley (Defra, 2007), which has been subjected to marine inundation caused by a rise in sea level at the end of the most recent glaciation (which ended c. 12,000 years ago). The Exe Estuary has a shoreline length of 40km, channel length of 16km, valley width 2km and a mouth width of 380m. It is classified as macrotidal with a range of 4m, whilst the River Exe (the main tributary) has a mean flow of 23m3/s, and a maximum of 371m3/s. At the mouth of the Exe Estuary, the sand spit of Dawlish Warren covers approximately three quarters of the estuary mouth width, and consequently potentially shelters the estuary from the coastal swell wave climate, as well as influencing the propagation of extreme tide levels. -

Display PDF in Separate

Stuart Bcckhurst x 2 Senior Scientist (Quality Planning) ) £e> JTH vJsrr U T W J Vcxg locafenvironment agency plan EXE ACTION PLAN PLAN from JULY 2000 to JULY 2005 Further copies of this Action Plan can be obtained from: LEAPs (Devon Area) The Environment Agency Exminster House Miller Way Exminster Devon EX6 8AS Telephone: (01392) 444000 E-mail: [email protected] Environment Agency Copyright Waiver This report is intended to be used widely and the text may be quoted, copied or reproduced in any way, provided that the extracts are not quoted out of context and that due acknowledgement is given to the Environment Agency. However, maps are reproduced from the Ordnance Survey 1:50,000 scale map by the Environment Agency with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number GD 03177G. Note: This is not a legally or scientifically binding document. Introduction 1 . Introduction The Environment Agency We have a wide range of duties and powers relating to different aspects of environmental management. These duties are described in more detail in Section Six. We are required and guided by Government to use these duties and powers in order to help achieve the objective of sustainable development. The Brundtland Commission defined sustainable development 'os development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs' At the heart of sustainable development is the integration of human needs and the environment within which we live. -

Exe Water Users Code

Exe Water Users Code A guide for water users on the Exe Estuary Exe Estuary Safety As well as being an ideal site for a wide range of Exe-pect the unexpected recreational activities, the Exe Estuary is also • Check tides, currents, wind and weather before home to an abundance of wildlife. Whilst exploring launching.* this beautiful area, please be considerate to other • Let someone ashore know your plans and expected users and wildlife. return time. This guide is aimed at all water users, from large • Always carry a suitable means of calling for help commercial boats to small kayaks. (e.g. waterproof VHF radio, mobile phone, whistle). • Carry the correct safety equipment, including a personal flotation device. Exe Estuary Navigation Byelaws Exe-plore the estuary Check for information at access points and adhere to the Navigation Byelaws (Max penalty £1,000): • Be visible: make sure lights are used at night, including for paddlesports. • Byelaw 4: Do not exceed speed limit as defined by charts and buoyage: 10 Knots Max. • Where appropriate, use launch points marked on the map. • Byelaw 4a: Power boat area: powerboating allowed in marked area when predicted tidal Exe-ist with other water users height is 3.8m or more. • Keep noise and wake to a minimum to not impact • Byelaw 5: Skiing only allowed in ski area marked upon other users and wildlife. by yellow buoys. • Access points / slipways should be kept clear • Byelaw 6: Navigate with due care and attention at all times and do not park vehicles on the and with reasonable care for others. -

Exe Activities

00456 for more information. more for www.exe-estuary.org magnificent 600 year old castle to explore. explore. to castle old year 600 magnificent Thanks to David Pick for Images supplied: www.exepics.co.uk supplied: Images for Pick David to Thanks to link the River Exe and Exeter Canal, see Canal, Exeter and Exe River the link to from leisure centres to amusement arcades and a and arcades amusement to centres leisure from Exmouth and Exeter. Canoe loops are being developed being are loops Canoe Exeter. and Exmouth There are various family attractions around the Exe the around attractions family various are There confront tidal waters. Rowing clubs operate from operate clubs Rowing waters. tidal confront Family Attractions Family Exe at Turf Hotel where the more experienced can experienced more the where Hotel Turf at Exe canal negotiating traditional locks. The canal joins the joins canal The locks. traditional negotiating canal during the season of September 1st - February 20th. 20th. February - 1st September of season the during From Exeter you can take a leisurely route down the down route leisurely a take can you Exeter From Certain duck and geese quarry species are pursued are species quarry geese and duck Certain by the Devon Wildfowling & Conservation Association. Conservation & Wildfowling Devon the by Rowing, Canoeing and Kayaking and Canoeing Rowing, Exmouth Town Council Dawlish Town Council Town Dawlish Council Town Exmouth acres of freshwater marsh at Exminster, are controlled are Exminster, at marsh freshwater of acres abide by the code of conduct. conduct. of code the by abide All wildfowling areas on the Estuary, such as the 30 the as such Estuary, the on areas wildfowling All ask in local outlets for more information and please and information more for outlets local in ask Wildfowling ) or ) www.exe-estuary.org ( website the Check activity. -

A River Valley Walk Between Source and Sea Along the Beautiful River Exe the Exe Valley Way a River Valley Walk Between Source and Sea Along the Beautiful River Exe

A river valley walk between source and sea along the beautiful River Exe The Exe Valley Way A river valley walk between source and sea along the beautiful River Exe A Guide for northbound and southbound The majority of the route follows footpaths walkers with a sketch map for each stage. and quiet country lanes where there is little traffic but there are brief stretches of busy The Exe Valley Way is a long distance route roads in Exeter and Tiverton. Care should be for walkers exploring the length of this taken at all times when walking on roads. beautiful river valley. It is almost 80km/ 50miles in length, stretching from the South Whilst this booklet does give a broad outline West Coast Path National Trail on the Exe of the waymarked route, it is emphasised Estuary to the village of Exford on the high that it would also be helpful to take an OS land of Exmoor National Park. An additional map along with you, particularly for the 12km/7.5 miles route links Exford to Exe footpath sections. Head, the source of the River Exe, high upon the moor. Most of the route follows beside OS Maps which cover the the River Exe. At the northern end of the Exe Valley Way: route, the route follows the River Barle, a Explorer No. 114 tributary of the River Exe, before rejoining Exeter & the Exe Valley (1:25 000) the Exe at Exford. Explorer OL9 Exmoor (1:25 000) The Exe Valley Way can be divided up into a series of 10 stages, most of which can be walked comfortably by most walkers in half a The Exe Valley day. -

Ambles-Leaflet-2-Web-1.Pdf

Exe Estuary Trail The Exe Estuary Trail is a 26 mile cycle AvocetAvocet and walkway along both sides of the estuary. It is mostly flat with a hard surface, giving easy walking that does AmblesAmbles not need specialist footwear. It is also suitable for wheelchairs and pushchairs. Walks from Exmouth Line stations The trail is accessible from Topsham, Exton, Lympstone Village and Exmouth Rail information for the Avocet Line stations as described below, giving a choice of short walks between stations • Journey time – approximately 30 minutes. on the line. • Regular half hourly services during the day – hourly Topsham in the evening. Turn right outside the station and right again • All trains stop at Exeter Central, Digby & Sowton, at the mini roundabout. Where the main Topsham, Lympstone Village and Exmouth. road bears left downhill, follow Elm Grove • St James’ Park and Polsloe Bridge have an hourly Road straight ahead, across the railway service in each direction as does Exton, which is a bridge, then turn left into Bowling Green request stop (Note that Lympstone Commando is Road. The off road trail starts at the bottom not available for public use). of the hill, turning left under the railway line. Distances: Exton 2 miles, Lympstone Village • Weekday and Saturday services from 6 am - midnight. 3½ miles, Exmouth 5½ miles. • Hourly service on Sundays from 9 am. Exton The fares are reasonably priced (for example the return fare The entrance to the south bound trail is 50 from Exeter St David’s to Exmouth in 2014 is £4.10 or £2.70 with yards from the station entrance. -

Review of Zones in the Exe Estuary

South East Devon Habitat Regulations Executive Committee Review of zones in the Exe Estuary Neil Harris, Habitat Regulations Delivery Manager October 2017 Legal comment/advice: The report identifies the legal background and details the process that has been gone through, including significant engagement / consultation, to arrive at a final set of proposals in respect of protective zones within the Exe Estuary. The recommendations from the EEMP report (with the further requirement in respect of restricting powerboat usage during certain times) appear sound and are reflected in the recommendations to the Executive Committee. Essentially, the wildlife refuges are areas that the Partnership will look to estuary users to respect and avoid for the reasons detailed in the report. However this is voluntary and therefore there is no basis for enforcement in the event users disregard what is proposed. The only aspect that might be capable of enforcement relates to the restriction on powerboating in the Exmouth Wildlife refuge during a certain period, however this will be for Exeter City Council to consider, as Harbour Authority, and progress accordingly – Recommendation 3 addresses this. Otherwise there are no legal implications requiring comment. Finance comment/advice: Actions and measures outlined in the report are within the financial resources allocated in the approved Business Plan. Review of zones in the Exe Estuary 2 of 17 Public Document: Yes Exemption: None Review date for None release Recommendations It is proposed that the Executive Committee: 1. Notes the outcome of the comprehensive consultation exercise on the introduction of Wildlife Refuges and records its thanks to the Exe Estuary Management Partnership for undertaking the initial stages of this exercise. -

Managing Flood Risk on the Severn Estuary

Managing flood and coastal erosion risk for the Exe Estuary Draft Strategy Consultation Document January 2013 1 We are the Environment Agency. It’s our job to look after your environment and make it a better place _ f or you, and for future generations. Your environment is the air you breathe, the water you drink and the ground you walk on. Working with business, Government and society as a whole, we are making your environment cleaner and healthier. The Environment Agency. Out there, making your environment a better place. 2 Locations covered by the Strategy Holcombe to Sandy Bay Clyst St Mary Page 18 Topsham, Countess Wear and Exminster Marshes East and West Banks of the River Page 19 Clyst Pages 16 and 17 Courtlands to Exton including Lympstone Powderham Banks and Page 15 the Kenn Valley Page 20 Exmouth Page 14 Starcross and Cockwood Page 21 Sandy Bay Page 12 Dawlish Warren Page 22 The Maer, Exmouth Page 13 Dawlish Warren to Holcombe Page 23 For Glossary of Terms see pages 25 and 26 3 Introduction Our Strategy needs to be We are keen to hear your views This consultation document sustainable into the future and and in this document we: summarises our draft Strategy so will consider as far as 100 • explain how the Strategy builds and recommendations to years ahead. on existing policies; manage flood and coastal • explain the current level of erosion risks for the whole of the Partners in the Strategy include flood risk and coastal erosion Exe Estuary, from Exmouth and Devon County Council, East and the effects of climate Dawlish to Exeter, including Devon District Council, change; adjacent coastline. -

Devon Redlands Area Profile: Supporting Documents

National Character 148: Devon Redlands Area profile: Supporting documents www.naturalengland.org.uk 1 National Character 148: Devon Redlands Area profile: Supporting documents Introduction National Character Areas map As part of Natural England’s responsibilities as set out in the Natural Environment White Paper1, Biodiversity 20202 and the European Landscape Convention3, we are revising profiles for England’s 159 National Character Areas (NCAs). These are areas that share similar landscape characteristics, and which follow natural lines in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a good decision-making framework for the natural environment. NCA profiles are guidance documents which can help communities to inform theirdecision-making about the places that they live in and care for. The informationthey contain will support the planning of conservation initiatives at a landscape scale, inform the delivery of Nature Improvement Areas and encourage broader partnership working through Local Nature Partnerships. The profiles will also help to inform choices about how land is managed and can change. Each profile includes a description of the natural and cultural features that shape our landscapes, how the landscape has changed over time, the current key drivers for ongoing change, and a broad analysis of each area’s characteristics and ecosystem services. Statements of Environmental Opportunity (SEOs) are suggested, which draw on this integrated information. The SEOs offer guidance on the critical issues, which could help to achieve sustainable growth and a more secure environmental future. 1 The Natural Choice: Securing the Value of Nature, Defra NCA profiles are working documents which draw on current evidence and (2011; URL: www.official-documents.gov.uk/document/cm80/8082/8082.pdf) 2 knowledge. -

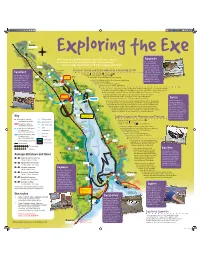

Exe Explorer Map and Info

%XPLORINGTHE%XE With help from public transport and ferries you can get %XQUISITE around much of the estuary in a day. Please take care The Exe Estuary is so important for crossing roads and railways and enjoy exploring the Exe. wildlife, particularly birds, that it is one of the most designated !SCENICCRUISEANDTRAINRIDEWITHALEISURELYSTROLL estuaries in the whole of Europe. This ensures %XCELLENT 9 1. Take ferry from Topsham 2 to Exmouth 56 that any development © RSPB Redshank Exeter Canal and Locks 2. Walk from Exmouth to Lympstone 27 plans or projects on are the oldest of their 3. Catch train from Lympstone back to Topsham the estuary must be type in the UK. They submitted to Natural Suitability: Walkers, cyclists, wheelchairs and pushchairs were built in 1567 to England for its assent. divert trade to Exeter Time: Three hours approx from Topsham, which at Distance on foot: Two miles approx that time was the second Estimated Cost: £7 adults, £4 children busiest port in the UK. Getting Started: A car park is available in Topsham on Holman Way that is a short walk from the quay. Buses and trains from Exeter to Topsham are frequent and reliable. Alternatively, ample 9 parking and public transport links are available in Exmouth if you reverse the route. To start in Topsham, follow signs to Lager Quay where Stuart Line Cruises depart for Exmouth when tides permit (check times by calling 01395 222144). The ferry takes from 1 to 1.5 hours depending on tides. %XOTIC From Exmouth Marina travel along Victoria Road and turn left on to Imperial Estuaries may look Road. -

East of Exe Buyer Locations Guide

East of Exe buyer locations guide At East of Exe we pride ourselves on knowing our ‘patch’ and are sure that knowledge gives us an edge when it comes to marketing properties for our customers. We specialise in the towns and villages east of the River Exe in Devon, an area of outstanding beauty, with the Jurassic coast line to the South and Dorset to the East. We recognise however that some purchasers may be less familiar with the area and have put together this brief overview to provide you with a guide as to the advantages and disadvantages of making your home in the major individual towns and villages. This is very much a personal opinion and we should emphasize that we think this is the best area in the whole of the UK to live, mainly because of its unique combination of sea, countryside, University City and communication links. Buying a new home is always a compromise and hopefully this guide will help in weighing up some of the locations of the properties available. Of course if you want any more details on this area please just ask, we love telling people about it. Exeter The historic Cathedral and University City of Exeter is also Devon’s capital and as such is the business, legal, retail, administrative, tourist and commercial centre for the region and it has maintained the charm and character associated with smaller cities. Its cultural heritage and traditional buildings are complemented by many recent sympathetic developments. Exeter is remarkably well served for transport with London 2 hours away by train, Exeter International Airport and the M5 motorway.