The Motto and the Enigma: Rhetoric and Knowledge in the Sixth Day of the Decameron

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assumption Parking Lot Rosary.Pub

Thank you for joining in this celebration Please of the Blessed Mother and our Catholic park in a faith. Please observe these guidelines: designated Social distancing rules are in effect. Please maintain 6 feet distance from everyone not riding parking with you in your vehicle. You are welcome to stay in your car or to stand/ sit outside your car to pray with us. space. Anyone wishing to place their own flowers before the statue of the Blessed Mother and Christ Child may do so aer the prayers have concluded, but social distancing must be observed at all mes. Please present your flowers, make a short prayer, and then return to your car so that the next person may do so, and so on. If you wish to speak with others, please remember to wear a mask and to observe 6 foot social distancing guidelines. Opening Hymn—Hail, Holy Queen Hail, holy Queen enthroned above; O Maria! Hail mother of mercy and of love, O Maria! Triumph, all ye cherubim, Sing with us, ye seraphim! Heav’n and earth resound the hymn: Salve, salve, salve, Regina! Our life, our sweetness here below, O Maria! Our hope in sorrow and in woe, O Maria! Sign of the Cross The Apostles' Creed I believe in God, the Father almighty, Creator of heaven and earth, and in Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord, who was conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Ponus Pilate, was crucified, died and was buried; he descended into hell; on the third day he rose again from the dead; he ascended into heaven, and is seated at the right hand of God the Father almighty; from there he will come to judge the living and the dead. -

Twenty-Fourth Sunday in Ordinary Time

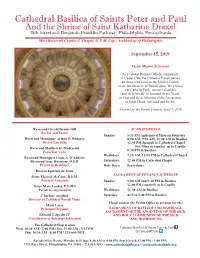

Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul And the Shrine of Saint Katharine Drexel 18th Street and Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Most Reverend Charles J. Chaput, O.F.M. Cap., Archbishop of Philadelphia September 15, 2019 Parish Mission Statement As a vibrant Roman Catholic community in Center City, the Cathedral Parish Serves all those who come to the Mother Church of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia. We profess our Catholic Faith, minister to others and welcome all, as founded on the Word of God and the celebration of the Sacraments of Jesus Christ, our Lord and Savior. Adopted by the Parish Council, April 5, 2016 Reverend Gerald Dennis Gill MASS SCHEDULE Rector and Pastor Sunday: 5:15 PM Anticipated Mass on Saturday Reverend Monsignor Arthur E. Rodgers 8:00 AM, 9:30 AM, 11:00 AM in Basilica Rector Emeritus 12:30 PM Spanish in Cathedral Chapel Sta. Misa en español, en la Capilla Reverend Matthew K. Biedrzycki 6:30 PM in Basilica Parochial Vicar Weekdays: 7:15 AM, 12:05 PM in Cathedral Chapel Reverend Monsignor Louis A. D’Addezio Saturdays: 12:05 PM in Cathedral Chapel Reverend Isaac Haywiser, O.S.B. Priests in Residence Holy Days: See website Deacon Epifanio de Jesus SACRAMENT OF PENANCE SCHEDULE Sister Eleanor McCann, R.S.M. Pastoral Associate Sunday: 9:00 AM and 5:30 PM in Basilica 12:00 PM (español) en la Capilla Sister Mary Luchia, P.V.M.I Parish Evangelization Weekdays: 11:30 AM in Basilica Charlene Angelini Saturday: 4:15 to 5:00 PM in Basilica Director of Cathedral Parish Music Please contact the Parish Office to arrange for the: Mark Loria SACRAMENT OF BAPTISM AND MARRIAGE, Principal Organist SACRAMENT OF THE ANOINTING OF THE SICK, Edward J. -

GOODSPEED MUSICALS TEACHER's INSTRUCTIONAL GUIDE MICHAEL GENNARO Executive Director

GOODSPEED MUSICALS TEACHER'S INSTRUCTIONAL GUIDE MICHAEL GENNARO Executive Director MICHAEL P. PRICE Founding Director presents Book by MARC ACITO Conceived by TINA MARIE CASAMENTO LIBBY Musical Adaptation by DAVID LIBBY Scenic Design by Costume Design by Lighting Design by Wig & Hair Design by KRISTEN ROBINSON ELIZABETH CAITLIN WARD KEN BILLINGTON MARK ADAM RAMPMEYER Creative Consultiant/Historian Assistant Music Director Arrangements and Original JOHN FRICKE WILLIAM J. THOMAS Orchestrations by DAVID LIBBY Orchestrations by Sound Design by DAN DeLANGE JAY HILTON Production Manager Production Stage Manager Casting by R. GLEN GRUSMARK BRADLEY G. SPACHMAN STUART HOWARD & PAUL HARDT Associate Producer Line Producer General Manager BOB ALWINE DONNA LYNN COOPER HILTON RACHEL J. TISCHLER Music Direction by MICHAEL O'FLAHERTY Choreographed by CHRIS BAILEY Directed by TYNE RAFAELI SEPT 16 - NOV 27, 2016 THE GOODSPEED TABLE OF CONTENTS How To Use the Guides........................................................................................................................................................................4 ABOUT THE SHOW: Show Synopsis..........................................................................................................................................................................5 The Characters..........................................................................................................................................................................7 Meet the Writers......................................................................................................................................................................8 -

Homer's Odyssey and the Image of Penelope in Renaissance Art Giancarlo FIORENZA

223 Homer's Odyssey and the Image of Penelope in Renaissance Art Giancarlo FIORENZA The epic heroine Penelope captured the Renaissance literary and artistic imagination, beginning with Petrarch and the recovery of Homer's poetry through its translation into Latin. Only a very small number of humanists in the 14'h century were able to read Homer in the Greek original, and Petrarch's friend Leontius Pilatus produced for him long-awaited Latin translations of the Iliad 1 and Odyssey in the 1360s • Profoundly moved by his ability to finally compre hend the two epics (albeit in translation), Petrarch composed a remarkable letter addressed to Homer in which he compares himself to Penelope: "Your Penelope cannot have waited longer nor with more eager expectation for her Ulysses than I did for you. At last, though, my hope was fading gradually away. Except for a few of the opening lines of certain books, from which there seemed to flash upon me the face of a friend whom I had been longing to behold, a momen tary glimpse, dim through the distance, or, rather, the sight of his streaming hair, as he vanished from my view- except for this no hint of a Latin Homer had come to me, and I had no hope of being able ever to see you face to face"'. The themes of anticipation and fulfillment, and longing and return that are associated with the figure of Penelope coincide with the rediscovery of ancient texts. To encounter Homer for the first time in a language with which one was 3 familiar was as much a personal as a literary experience • As Nancy Struever observes, Petrarch's Le Familiari, a collection of letters addressed to contemporary friends and ancient authors, values friendship and intimate exchange because 4 it leads to knowledge and affective reward • Books on their own (Le Familiari, XII, 6) constituted surrogate friends with whom Petrarch could correspond, con verse, exchange ideas, and share his affections. -

Petrarch and Boccaccio Mimesis

Petrarch and Boccaccio Mimesis Romanische Literaturen der Welt Herausgegeben von Ottmar Ette Band 61 Petrarch and Boccaccio The Unity of Knowledge in the Pre-modern World Edited by Igor Candido An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. The Open Access book is available at www.degruyter.com. ISBN 978-3-11-042514-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-041930-6 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-041958-0 ISSN 0178-7489 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 license. For more information, see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2018 Igor Candido, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Typesetting: Konvertus, Haarlem Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Dedicated to Ronald Witt (1932–2017) Contents Acknowledgments IX Igor Candido Introduction 1 H. Wayne Storey The -

Petrarch and Boccaccio: the Rewriting of Griselda's Tale

Heliotropia 16-17 (2019-20) http://www.heliotropia.org Petrarch and Boccaccio: The Rewriting of Griselda’s Tale (Dec. 10.10). A Rhetorical Debate on Latin and Vernacular Languages∗ he story of Griselda has always raised many interpretative problems. One could perhaps suggest that when Boccaccio has his storytellers T quarrel over the meaning of the last novella, he is anticipating the critical controversy that this text has sparked throughout its long and suc- cessful career in Europe. The first critic and reader of Boccaccio’s tale was Petrarch, whom Boc- caccio met for the first time in Florence in 1350. The following year, Boccac- cio met the elder poet in Padua to invite him, unsuccessfully, to assume a position as a professor at Florence’s Studium. The cultural and personal bond between Boccaccio and Petrarch dates back to that time.1 This friend- ship, marked by intense correspondence and mutual invitations, was always affected by an inherent tension over Dante’s poetics. For Petrarch, the Com- media was irreconcilable with his well-known aristocratic and elitist con- ception of literature; Boccaccio, however, soon became Dante’s ‘advocate,’ promoting the poetics of the Commedia.2 The Dante debate between Boccaccio and Petrarch expresses a differ- ence of opinion concerning vernacular literature, its dignity and its appro- priateness for dealing with issues traditionally entrusted to Latin. Famili- ares 21.15, addressed to Boccaccio, is an important token of Petrarch’s atti- tude towards Dante. Rejecting any charge of envy, Petrarch presents the is- sue of language as the real reason he dismisses Dante’s poetry: ∗ I would like to thank Prof. -

Jennifer Rushworth

Jennifer Rushworth Petrarch’s French Fortunes: negotiating the relationship between poet, place, and identity in the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries This article reconsiders Petrarch’s French afterlife by juxtaposing a time of long-recognised Petrarchism — the sixteenth century — with a less familiar and more modern Petrarchist age, the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Of particular interest is how French writers from both periods understand and represent Petrarch’s associations with place. This variously proposed, geographically defined identity is in turn regional (Tuscan/Provençal) and national (Italian/French), located by river (Arno/Sorgue) and city (Florence/Avignon). I argue that sixteenth-century poets stress Petrarch’s foreignness, thereby keeping him at a safe distance, whereas later writers embrace Petrarch as French, drawing the poet closer to (their) home. The medieval Italian poet Francesco Petrarca (known in English as Petrarch, in French as Pétrarque) is the author of many works in Latin and in Italian, in poetry and in prose (for the most complete and accessible account, see Kirkham and Maggi). Since the sixteenth century, however, his fame has resided in one particular vernacular form: the sonnet. In his poetic collection Rerum vulgarium fragmenta, more commonly and simply known as the Canzoniere, 317 of the total 366 are sonnets. These poems reflect on the experience of love and later of grief, centred on the poet’s beloved Laura, and have been so often imitated by later poets as to have given rise to a poetic movement named after the poet: Petrarchism. In the words of Jonathan Culler, “Petrarch’s Canzoniere established a grammar for the European love lyric: a set of tropes, images, oppositions (fire and ice), and typical scenarios that permitted generations of poets throughout Europe to exercise their ingenuity in the construction of love sonnets” (69). -

Locating Boccaccio in 2013

Locating Boccaccio in 2013 Locating Boccaccio in 2013 11 July to 20 December 2013 Mon 12.00 – 5.00 Tue – Sat 10.00 – 5.00 Sun 12.00 – 5.00 The John Rylands Library The University of Manchester 150 Deansgate, Manchester, M3 3EH Designed by Epigram 0161 237 9660 1 2 Contents Locating Boccaccio in 2013 2 The Life of Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375) 3 Tales through Time 4 Boccaccio and Women 6 Boccaccio as Mediator 8 Transmissions and Transformations 10 Innovations in Print 12 Censorship and Erotica 14 Aesthetics of the Historic Book 16 Boccaccio in Manchester 18 Boccaccio and the Artists’ Book 20 Further Reading and Resources 28 Acknowledgements 29 1 Locating Boccaccio Te Life of Giovanni in 2013 Boccaccio (1313-1375) 2013 is the 700th anniversary of Boccaccio’s twenty-first century? His status as one of the Giovanni Boccaccio was born in 1313, either Author portrait, birth, and this occasion offers us the tre corone (three crowns) of Italian medieval in Florence or nearby Certaldo, the son of Decameron (Venice: 1546), opportunity not only to commemorate this literature, alongside Dante and Petrarch is a merchant who worked for the famous fol. *3v great author and his works, but also to reflect unchallenged, yet he is often perceived as Bardi company. In 1327 the young Boccaccio upon his legacy and meanings today. The the lesser figure of the three. Rather than moved to Naples to join his father who exhibition forms part of a series of events simply defining Boccaccio in automatic was posted there. As a trainee merchant around the world celebrating Boccaccio in relation to the other great men in his life, Boccaccio learnt the basic skills of arithmetic 2013 and is accompanied by an international then, we seek to re-present him as a central and accounting before commencing training conference held at the historic Manchester figure in the classical revival, and innovator as a canon lawyer. -

Monica Berté - Francisco Rico

MONICA BERTÉ - FRANCISCO RICO TRE O QUATTRO EPIGRAMMI DI PETRARCA I M ONICA B ERTÉ SULL’ANTOLOGIA DELLE POESIE D’OCCASIONE DI PETRARCA* Nel 1929 Konrad Burdach, con la collaborazione di Richard Kienast, pubblicava nel quarto volume di Vom Mittelalter zur Reformation le poesie d’occasione di Francesco Petrarca conservate nel manoscritto di Olomouc, Státní Oblastní Archiv, C. O. 5091; diciannove componi- * Ringrazio per la generosa e preziosa lettura di queste pagine Rossella Bianchi, Vincenzo Fera, Alessandro Pancheri e Silvia Rizzo. Ulteriormente Francisco Rico mi ha dato utili riferimenti bibliografici, che mi hanno permesso di affinare il mio lavoro. 1 Vd. K. BURDACH, Vom Mittelalter zur Reformation. Aus Petrarcas ältestem deutschen Schülerkreise. Texte und Untersuchungen, unter Mitwirkung R. KIENA- STS, IV, Berlin 1929 (con correzioni in Vom Mittelalter zur Reformation. Briefwe- chsel des Cola di Rienzo, II/5, Berlin 1929, 517-19). Lo stesso Burdach tornava sulle poesie d’occasione in due diverse sedi: Unbekannte Gelegenheitsgedichte Petrarcas nach einer Olmützer Handschrift aus dem Anfang des 15. Jahrhunderts, «Die Antike. Zeitschrift für Kunst und Kultur des klassischen Altertums», 10 (1934), 122-43 e Die Sammlung kleiner lateinischer Gelegenheitsgedichte Petrar- cas, «Sitzungsberichte der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften», Philo- sophisch-historische Klasse, 1935, 120-36. Nel primo dei due articoli Burdach dava nuovamente il testo latino, privo di apparato ma con qualche variante e con traduzione tedesca a fronte, dei carmina latini di Petrarca traditi dal manoscritto di Olomouc e nel secondo ridiscuteva sulla base di un nuovo codice, emerso dopo la 2 MONICA BERTÉ - FRANCISCO RICO menti in tutto, vari per metro, tono, data (dai primi, la gran parte, com- posti nel 1341 all’ultimo, il celebre inno all’Italia, del 1353) e destina- tario (alcuni ricavabili dalle rime o, più spesso, dalle didascalie: Lud- ovico Santo di Beringen, Filippo di Cabassoles, Roberto d’Angiò re di Napoli, Orso dell’Anguillara, Luchino Visconti, Gui de Boulogne, Lello Tosetti). -

“Clean Hands” Doctrine

Announcing the “Clean Hands” Doctrine T. Leigh Anenson, J.D., LL.M, Ph.D.* This Article offers an analysis of the “clean hands” doctrine (unclean hands), a defense that traditionally bars the equitable relief otherwise available in litigation. The doctrine spans every conceivable controversy and effectively eliminates rights. A number of state and federal courts no longer restrict unclean hands to equitable remedies or preserve the substantive version of the defense. It has also been assimilated into statutory law. The defense is additionally reproducing and multiplying into more distinctive doctrines, thus magnifying its impact. Despite its approval in the courts, the equitable defense of unclean hands has been largely disregarded or simply disparaged since the last century. Prior research on unclean hands divided the defense into topical areas of the law. Consistent with this approach, the conclusion reached was that it lacked cohesion and shared properties. This study sees things differently. It offers a common language to help avoid compartmentalization along with a unified framework to provide a more precise way of understanding the defense. Advancing an overarching theory and structure of the defense should better clarify not only when the doctrine should be allowed, but also why it may be applied differently in different circumstances. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 1829 I. PHILOSOPHY OF EQUITY AND UNCLEAN HANDS ...................... 1837 * Copyright © 2018 T. Leigh Anenson. Professor of Business Law, University of Maryland; Associate Director, Center for the Study of Business Ethics, Regulation, and Crime; Of Counsel, Reminger Co., L.P.A; [email protected]. Thanks to the participants in the Discussion Group on the Law of Equity at the 2017 Southeastern Association of Law Schools Annual Conference, the 2017 International Academy of Legal Studies in Business Annual Conference, and the 2018 Pacific Southwest Academy of Legal Studies in Business Annual Conference. -

The Renaissance, and the Rediscovery of Plato and the Greeks

Click here for Full Issue of Fidelio Volume 12, Number 3, Fall 2003 The Renaissance, and The Rediscovery of Plato And the G by Torbjörn Jerlerup t was in the Midland between the ‘ famous rivers Po and Ticino and IAdda and others, whence some say our Milan derives its name, on the ninth day of October, in the year of this last age of the world the 1360th.”1 For the people who lived in the Italian city of Milan or in one of its surrounding villages, it might have looked like an ordinary, but cold, autumn morning. It was Friday. The city council and the bishop of Milan were probably quarrelling about the construction of a new cathedral in the city. The construction would not start for another 25 years. The university professors and the barbers (the doctors Alinari/Art Resource, NY of the time), were probably worried Domenico di Michelino, “Dante Alighieri Reading His Poem,” 1465 about rumors of a new plague, the (detail). The Cathedral of Florence, topped by Brunelleschi’s Dome, third since the Great Plague in 1348, appears to Dante’s left. and the townspeople were probably complaining about taxes, as usual. The Great minds of ancient Greece farmers, who led their cattle to pas- (clockwise from top): Homer, Plato, ture, were surely complaining about Solon, Aeschylus, Sophocles. the weather, as it had been unusually unstable. 36 © 2003 Schiller Institute, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission strictly prohibited. The Granger Collection of Plato EIRNS/Philip Ulanowsky Greeks The Granger Collection If they were not too busy with their cows, they perhaps caught a glimpse of a monk riding along the grassy, mud-ridden path that was part of the main road between the cities of Florence and The Granger Collection Milan. -

Private Higher Education Institutions Faculty-Student Ratio: AY 2017-18

Table 11. Private Higher Education Institutions Faculty-Student Ratio: AY 2017-18 Number of Number of Faculty/ Region Name of Private Higher Education Institution Students Faculty Student Ratio 01 - Ilocos Region The Adelphi College 434 27 1:16 Malasiqui Agno Valley College 565 29 1:19 Asbury College 401 21 1:19 Asiacareer College Foundation 116 16 1:7 Bacarra Medical Center School of Midwifery 24 10 1:2 CICOSAT Colleges 657 41 1:16 Colegio de Dagupan 4,037 72 1:56 Dagupan Colleges Foundation 72 20 1:4 Data Center College of the Philippines of Laoag City 1,280 47 1:27 Divine Word College of Laoag 1,567 91 1:17 Divine Word College of Urdaneta 40 11 1:4 Divine Word College of Vigan 415 49 1:8 The Great Plebeian College 450 42 1:11 Lorma Colleges 2,337 125 1:19 Luna Colleges 1,755 21 1:84 University of Luzon 4,938 180 1:27 Lyceum Northern Luzon 1,271 52 1:24 Mary Help of Christians College Seminary 45 18 1:3 Northern Christian College 541 59 1:9 Northern Luzon Adventist College 480 49 1:10 Northern Philippines College for Maritime, Science and Technology 1,610 47 1:34 Northwestern University 3,332 152 1:22 Osias Educational Foundation 383 15 1:26 Palaris College 271 27 1:10 Page 1 of 65 Number of Number of Faculty/ Region Name of Private Higher Education Institution Students Faculty Student Ratio Panpacific University North Philippines-Urdaneta City 1,842 56 1:33 Pangasinan Merchant Marine Academy 2,356 25 1:94 Perpetual Help College of Pangasinan 642 40 1:16 Polytechnic College of La union 1,101 46 1:24 Philippine College of Science and Technology 1,745 85 1:21 PIMSAT Colleges-Dagupan 1,511 40 1:38 Saint Columban's College 90 11 1:8 Saint Louis College-City of San Fernando 3,385 132 1:26 Saint Mary's College Sta.