Getting from Conflict to Communion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fourth Crusade Was No Different

Coastal Carolina University CCU Digital Commons Honors College and Center for Interdisciplinary Honors Theses Studies Fall 12-15-2016 The ourF th Crusade: An Analysis of Sacred Duty Dale Robinson Coastal Carolina University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/honors-theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Robinson, Dale, "The ourF th Crusade: An Analysis of Sacred Duty " (2016). Honors Theses. 4. https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/honors-theses/4 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College and Center for Interdisciplinary Studies at CCU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of CCU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Robinson 1 The crusades were a Christian enterprise. They were proclaimed in the name of God for the service of the church. Religion was the thread which bound crusaders together and united them in a single holy cause. When crusaders set out for a holy war they took a vow not to their feudal lord or king, but to God. The Fourth Crusade was no different. Proclaimed by Pope Innocent III in 1201, it was intended to recover Christian control of the Levant after the failure of past endeavors. Crusading vows were exchanged for indulgences absolving all sins on behalf of the church. Christianity tied crusaders to the cause. That thread gradually came unwound as Innocent’s crusade progressed, however. Pope Innocent III preached the Fourth Crusade as another attempt to secure Christian control of the Holy Land after the failures of previous crusades. -

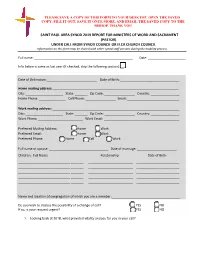

UNDER CALL from SYNOD COUNCIL OR ELCA CHURCH COUNCIL Information on This Form May Be Shared with Other Synod Staff Persons During the Mobility Process

PLEASE SAVE A COPY OF THIS FORM TO YOUR DESKTOP, OPEN THE SAVED COPY, FILL IT OUT, SAVE IT ONCE MORE, AND EMAIL THE SAVED COPY TO THE BISHOP. THANK YOU SAINT PAUL AREA SYNOD 2019 REPORT FOR MINISTERS OF WORD AND SACRAMENT (PASTOR) UNDER CALL FROM SYNOD COUNCIL OR ELCA CHURCH COUNCIL Information on this form may be shared with other synod staff persons during the mobility process Full name: _______________________________________________________ Date: _____________________ Info below is same as last year (if checked, skip the following section):__ Date of Ordination:____________________________ Date of Birth: _________________________________ Home mailing address: ______________________________________________________________________ City: _____________________ State: _______ Zip Code: _________________ Country: ________________ Home Phone: _______________ Cell Phone: _________________ Email: _____________________________ Work mailing address: _______________________________________________________________________ City: _____________________ State: _______ Zip Code: _________________ Country: ________________ Work Phone: _________________________ Work Email: __________________________________________ Preferred Mailing Address: Home Work Preferred Email: Home Work Preferred Phone: Home Cell Work Full name of spouse: _________________________________ Date of marriage: ______________________ Children: Full Name Relationship Date of Birth _____________________________ _______ _________________________ ________________________ _____________________________ -

Globalization and Orthodox Christianity: a Glocal Perspective

religions Article Globalization and Orthodox Christianity: A Glocal Perspective Marco Guglielmi Human Rights Centre, University of Padua, Via Martiri della Libertà, 2, 35137 Padova, Italy; [email protected] Received: 14 June 2018; Accepted: 10 July 2018; Published: 12 July 2018 Abstract: This article analyses the topic of Globalization and Orthodox Christianity. Starting with Victor Roudometof’s work (2014b) dedicated to this subject, the author’s views are compared with some of the main research of social scientists on the subject of sociological theory and Eastern Orthodoxy. The article essentially has a twofold aim. Our intention will be to explore this new area of research and to examine its value in the study of this religion and, secondly, to further investigate the theory of religious glocalization and to advocate the fertility of Roudometof’s model of four glocalizations in current social scientific debate on Orthodox Christianity. Keywords: Orthodox Christianity; Globalization; Glocal Religions; Eastern Orthodoxy and Modernity Starting in the second half of the nineteen-nineties, the principal social scientific studies that have investigated the relationship between Orthodox Christianity and democracy have adopted the well-known paradigm of the ‘clash of civilizations’ (Huntington 1996). Other sociological research projects concerning religion, on the other hand, have focused on changes occurring in this religious tradition in modernity, mainly adopting the paradigm of secularization (in this regard see Fokas 2012). Finally, another path of research, which has attempted to develop a non-Eurocentric vision, has used the paradigm of multiple modernities (Eisenstadt 2000). In his work Globalization and Orthodox Christianity (2014b), Victor Roudometof moves away from these perspectives. -

The True Orthodox Church in Front of the Ecumenism Heresy

† The True Orthodox Church in front of the Ecumenism Heresy Dogmatic and Canonical Issues I. Basic Ecclesiological Principles II. Ecumenism: A Syncretistic Panheresy III. Sergianism: An Adulteration of Canonicity of the Church IV. So-Called Official Orthodoxy V. The True Orthodox Church VI. The Return to True Orthodoxy VII. Towards the Convocation of a Major Synod of the True Orthodox Church † March 2014 A text drawn up by the Churches of the True Orthodox Christians in Greece, Romania and Russian from Abroad 1 † The True Orthodox Church in front of the Ecumenism Heresy Dogmatic and Canonical Issues I. Basic Ecclesiological Principles The True Orthodox Church has, since the preceding twentieth century, been struggling steadfastly in confession against the ecclesiological heresy of ecumenism1 and, as well, not only against the calendar innovation that derived from it, but also more generally against dogmatic syncretism,2 which, inexorably and methodically cultivating at an inter-Christian3 and inter-religious4 level, in sundry ways and in contradiction to the Gospel, the concurrency, commingling, and joint action of Truth and error, Light and darkness, and the Church and heresy, aims at the establishment of a new entity, that is, a community without identity of faith, the so-called body of believers. * * * • In Her struggle to confess the Faith, the True Orthodox Church has applied, and 5 continues to embrace and apply, the following basic principles of Orthodox ecclesiology: 1. The primary criterion for the status of membership in the Church of Christ is the “correct and saving confession of the Faith,” that is, the true, exact and anti innova- tionist Orthodox Faith, and it is “on this rock” (of correct confession) that the Lord 6 has built His Holy Church. -

Saint Augustine • Whose Full Name Was Aurelius Augustinus • Was Born

Saint Augustine • The grand style is not quite as elegant as the mixed style, but is exciting and heartfelt, with the purpose of igniting the same passion in the • Whose full name was Aurelius Augustinus students' hearts. • was born in a.d. 354, in the city of Tagaste, in the Roman North African province of Numidia (now Algeria). • Augustine proposed that evil could not exist within God, nor be created •was an early Christian theologian whose writings were very influential in by God, and is instead a by-product of God's creativity. the development of Western Christianity and Western philosophy. • He believed that this evil will, present in the human soul, was a •Augustine developed the concept of the Catholic Church as a spiritual City corruption of the will given to humans by God, making suffering a just of God punishment for the sin of humans. •He was ordained as a priest in 391, and in 396 he became the bishop of • Augustine believed that a physical Hell exists, but that physical Hippo, a position he undertook with conviction and would hold until his punishment is secondary to the punishment being separated from God. death. •Augustine died in the year 430 in his bed, reading the Psalms, as the Vandals began to attack Hippo. Teachings and beliefs • Augustine believed that dialogue/dialectic/discussion is the best means for learning, and this method should serve as a model for learning encounters between teachers and students. • Augustine stressed the importance of showing that type of student the difference between "having words and having understanding," and of helping the student to remain humble with his acquisition of knowledge. -

Generous Orthodoxy - Doing Theology in the Spirit

Generous Orthodoxy - Doing Theology in the Spirit When St Mellitus began back in 2007, a Memorandum of Intent was drawn up outlining the agreement for the new College. It included the following paragraph: “The Bishops and Dean of St Mellitus will ensure that the College provides training that represents a generous Christian orthodoxy and that trains ordinands in such a way that all mainstream traditions of the Church have proper recognition and provision within the training.” That statement reflected a series of conversations that happened at the early stages of the project, and the desire from everyone involved that this new college would try in some measure to break the mould of past theological training. Most of us who had trained at residential colleges in the past had trained in party colleges which did have the benefit of strengthening the identity of the different rich traditions of the church in England but also the disadvantage of often reinforcing unhelpful stereotypes and suspicion of other groups and traditions within the church. I remember discussing how we would describe this new form of association. It was Simon Downham, the vicar of St Paul’s Hammersmith who came up with the idea of calling it a “Generous Orthodoxy”, and so the term was introduced that has become so pivotal to the identity of the College ever since. Of course, Simon was not the first to use the phrase. It was perhaps best known as the title of a book published in 2004 by Brian McLaren, a book which was fairly controversial at the time. -

The Eastern Mission of the Pontifical Commission for Russia, Origins to 1933

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations August 2017 Lux Occidentale: The aE stern Mission of the Pontifical Commission for Russia, Origins to 1933 Michael Anthony Guzik University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Guzik, Michael Anthony, "Lux Occidentale: The Eastern Mission of the Pontifical ommiC ssion for Russia, Origins to 1933" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 1632. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1632 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LUX OCCIDENTALE: THE EASTERN MISSION OF THE PONTIFICAL COMMISSION FOR RUSSIA, ORIGINS TO 1933 by Michael A. Guzik A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee August 2017 ABSTRACT LUX OCCIDENTALE: THE EASTERN MISSION OF THE PONTIFICAL COMMISSION FOR RUSSIA, ORIGINS TO 1933 by Michael A. Guzik The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2017 Under the Supervision of Professor Neal Pease Although it was first a sub-commission within the Congregation for the Eastern Churches (CEO), the Pontifical Commission for Russia (PCpR) emerged as an independent commission under the presidency of the noted Vatican Russian expert, Michel d’Herbigny, S.J. in 1925, and remained so until 1933 when it was re-integrated into CEO. -

The Synod Process

The Synod Process I Convocation and Preparation of the Synod 2 Preparatory Commission 1 The bishop convenes the synod with the consultation of the • Members of the preparatory commission are chosen by the bishop. Presbyteral Council. • The preparatory commission assists the bishop in organizing and preparing for the synod. • The bishop establishes a synodal secretariat and possibly a press office. 1 2 4 Preparatory phases of synod • Spiritual, catechetical and formational preparation 4 1. All are invited to pray for the ongoing intention of the synod and its results, that it might become an authentic 3 event of grace for the Church. 3 Publication of the Synodal 2. All should be informed on the nature and Directory purpose of the synod and the scope of its The Synodal Directory includes: deliberations. 1. composition of the synod; • Diocesan Consultation 2. norms by which elections of synodal members are to be conducted; 1. The faithful and the clergy of the Diocese 3. various offices to be exercised by the synod; are encouraged to express their needs, 4. procedural norms of the synod meetings. desires, challenges and opinions regarding the synod topics. 2. Meetings will take place at each parish, then deanery, to discuss synod topics. II Conducting the Synod • Determining the questions 1. The bishop determines the • The actual synod consists of the synodal sessions, questions on which the synodal typically in the cathedral. debate will concentrate. • Members of the synod make the profession of the faith before commencing synodal discussions. • Themes to be examined are introduced from a brief report; discussion begins. -

The Long Way to a Common Easter Date a Catholic and Ecumenical Perspective

Journal of Eastern Christian Studies 63(3-4), 353-376. doi: 10.2143/JECS.63.3.2149626 © 2011 by Journal of Eastern Christian Studies. All rights reserved. THE LONG WAY TO A COMMON EASTER DATE A CATHOLIC AND ECUMENICAL PERSPECTIVE BERT GROEN* 1. INTRODUCTION ‘The feast of feasts, the new drink, the famous and holy day…’ With these words and in other poetic language, St. John of Damascus (ca. 650 - before 754) extols Easter in the paschal canon attributed to him.1 The liturgical calendars of both Eastern and Western Christianity commemorate this noted Eastern theologian on December 4. Of course, not only on Easter, but in any celebration of the Eucharist, the paschal mystery is being commemo- rated. The Eucharist is the nucleus of Christian worship. Preferably on the Lord’s Day, the first day of the week, Christians assemble to hear and expe- rience the biblical words of liberation and reconciliation, to partake of the bread and cup of life which have been transformed by the Holy Spirit, to celebrate the body of Christ and to become this body themselves. Hearing and doing the word of God, ritually sharing His gifts and becoming a faith- ful Eucharistic community make the Church spiritually grow. Yet, it is the Easter festival, the feast of the crucified and resurrected Christ par excellence, in which all of this is densely and intensely celebrated. The first Christians were Jews who believed that in Jesus of Nazareth, the Messiah had come. Initially, they celebrated the festivals of the Jewish calendar, * Bert Groen is professor of liturgical studies and sacramental theology at the University of Graz, Austria. -

Greetings: Christopher Hill

DOC ID GREET_01 LANGUAGE ENGLISH ORIGINAL English Welcome to General Assembly of CEC Most Reverend Brothers and Sisters, Sisters and Brothers in Christ Welcome! Bienvenue! Herzlich willkommen! Dobra pozhalovat! In our host country of Serbia this is the Week of Pentecost. For Western Churches we are just a week or so from Pentecost. Despite this I fear your President – outgoing President! – does not have the apostolic gift of tongues recounted in the Acts of the Apostles. So hereafter in English. I do not intend to bore you by repeating my written Introduction/Foreword. But I simply remind you that CEC has in these last years been through a metamorphosis. We have changed structure and shape. In my written Introduction/Foreword I remind you of the journey from Lyons, ten years ago, through Budapest, five years ago, to today in Novi Sad, Serbia. But after reminding you of our changing history, I also emphasised that here at this Assembly we are looking for a renewed Christian vision for Europe; a Europe wider than the European Union as it is today, but also a Europe with a vision much wider than simple economic growth. So our themes of Witness, Justice and Hospitality. What is the Churches’ contribution to a vision for the Future of Europe? First, we must remember our history. This is not all good news for a vision of Europe. There was the Great Schism between Eastern and Western Christianity. We give it a formal date in 1054 but it happened long before that, East and West having drifted apart with the collapse of the Western Roman Empire and the rise of the Holy Roman Empire, and the Crusades, and the continuance of the Eastern, Byzantine Roman Empire right up until the conquest of Constantinople in 1453 by the Ottoman Turks. -

The Religious Foundations of Western Law

Catholic University Law Review Volume 24 Issue 3 Spring 1975 Article 4 1975 The Religious Foundations of Western Law Harold J. Berman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Harold J. Berman, The Religious Foundations of Western Law, 24 Cath. U. L. Rev. 490 (1975). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol24/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RELIGIOUS FOUNDATIONS OF WESTERN LAWt Harold 1. Berman* I. THE WESTERN LEGAL TRADITION The Western legal tradition, like Western civilization as a whole, is under- going in the 20th century a crisis greater than any other in its history, since it is a crisis generated not only from within Western experience but also from without. From within, social, economic, and political transformations of un- precedented magnitude have put a tremendous strain upon traditional legal institutions and legal values in virtually all countries of the West. Yet there have been other periods of revolutionary upheaval in previous centuries, and we have somehow survived them. What is new is the confrontation with non- Western civilizations and non-Western philosophies. In the past, Western man has confidently carried his law with him throughout the world. The world today, however, is more suspicious than ever before of Western "legal- ism." Eastern man and Southern man offer other alternatives. -

The Synod for the Amazon

THE SYNOD FOR THE AMAZON Marcelo Barros • The divine revelation that arrives late1 • ABSTRACT It is good news that the Synod of Catholic Bishops from around the world, convened by Pope Francis and which will take place in October in Rome, has been prepared with extensive consultation with Amazonian communities and civil organizations working with them. The novelty of this Synod is the call for the Church, instead of acting as a teacher, to listen and hear the voice of the Amazon. In doing so, the Church will discover how to confront the challenges and new possibilities for its mission; a new vision and in opposition to the colonization in which it was complicit. KEYWORDS Spiritual listening | Catholic Church | Earth cry | Amazon peoples | Walk together • SUR 29 - v.16 n.29 • 133 - 138 | 2019 133 THE SYNOD FOR THE AMAZON There is no doubt that for the peoples of the Amazon, the news that Pope Francis convoked a Synod of Roman-Catholic Bishops from around the world to reflect about the appeals that the Amazon is making to the Universal Church (the body of Christian churches worldwide) was well-received. As Dom Roque Paloschi, president of the Indigenist Missionary Council in Brazil (Conselho Indigenista Missionário - CIMI), affirmed, “the Synod for the Amazon practically began in January of 2018, in Puerto Maldonado (Peru), during the Pope’s meeting with Amazonian people.”2 The Synod of Bishops is an institution that continues an old church custom and enacts the Church’s vocation as a sign and instrument of unity for all of humanity.