Separating Water and Politics Isn't Easy in California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greenspace | Los

NOAA may prohibit Navy sonar testing at marine mammal 'hot spots' | Greenspace | Los ... Page 1 of 3 Subscribe Place An Ad Jobs Cars Real Estate Rentals Foreclosures More Classifieds ENVIRONMENT LOCAL U.S. & WORLD BUSINESS SPORTS ENTERTAINMENT HEALTH LIVING TRAVEL OPINION MORE Search GO L.A. NOW POLITICS CRIME EDUCATION O.C. WESTSIDE NEIGHBORHOODS ENVIRONMENT OBITUARIES HOT LIST Stay connected: Greenspace ENVIRONMENTAL NEWS FROM CALIFORNIA AND BEYOND advertisement « Previous Post | Greenspace Home NOAA may prohibit Navy sonar testing at marine mammal 'hot spots' January 22, 2010 | 2:49 pm Marine mammal "hot spots" in areas including Southern California's coastal waters may become off limits to testing of a type of Navy sonar linked to the deaths of whales under a plan announced this week by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. NOAA also called for development of a system for estimating the "comprehensive sound budget for the oceans," which could help reduce human sources of noise -- vessel traffic, sonar and construction activities -- that degrade the environment in which sound-sensitive species communicate. The plans were revealed in a letter from NOAA Administrator Jane Lubchenco to the White House Council on Environmental Quality. In the letter, Lubchenco said her goal is to reduce adverse effects on marine mammals resulting from the Navy's training exercises. About the Bloggers Environmentalists contend that sonar has a possibly deafening effect on marine mammals. Studies around the world have shown the piercing underwater sounds cause whales to flee in panic or to dive Bettina Boxall too deeply. Whales have been found beached in Greece, the Canary Islands and the Bahamas after Susan Carpenter Tiffany Hsu sonar was used in the area. -

Beyond Drought: Water Rights in the Age of Permanent Depletion

Beyond Drought: Water Rights in the Age of Permanent Depletion Burke W. Griggs* INTRODUCTION Drought affects more North Americans than any other natural hazard.1 Over the past two decades, it has returned to the American West with historic intensity. The long drought of 2000–06 across the Great Plains resulted in record low stream flows and record low reservoir levels; in Kansas, it compelled a record number of surface water rights curtailments.2 The Colorado River Basin is caught in the throes of a fifteen-year drought that has reduced water levels in the two largest reservoirs in the United States, Lake Mead and Lake Powell, to unprecedented lows.3 California is experiencing its worst drought since 1976–77, and possibly since 1580.4 Chronic water shortages have driven at least ten states to litigation presently before the Supreme Court of the United States, and most of these cases involve western waters.5 Unlike the Dust Bowl era, when Farm Security Administration photographs of dry streambeds and drought-stricken fields * Consulting Professor, Bill Lane Center for the American West, Stanford University; Special Assistant Attorney General, State of Kansas. 1. Kansas Drought Watch, U.S.GEOLOGICAL SURVEY, http://ks.water.usgs.gov/ks-drought (last visited May 13, 2014). 2. Id. 3. Michael Wines, Colorado River Drought Forces a Painful Reckoning for States, N.Y. TIMES, Jan. 5, 2014, at A1; Felicity Barringer, Lake Mead Hits Record Low Level, N.Y. TIMES, (Oct. 18, 2010, 2:05 PM), http://green.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/10/18/lake-mead-hits-record-low-level. -

Litigation, Argumentative Strategies, and Coalitions in the Same-Sex Marriage Struggle

Florida State University College of Law Scholarship Repository Scholarly Publications Winter 2012 The Terms of the Debate: Litigation, Argumentative Strategies, and Coalitions in the Same-Sex Marriage Struggle Mary Ziegler Florida State University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/articles Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, and the Litigation Commons Recommended Citation Mary Ziegler, The Terms of the Debate: Litigation, Argumentative Strategies, and Coalitions in the Same- Sex Marriage Struggle, 39 FLA. ST. U. L. REV. 467 (2012), Available at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/articles/332 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE TERMS OF THE DEBATE: LITIGATION, ARGUMENTATIVE STRATEGIES, AND COALITIONS IN THE SAME-SEX MARRIAGE STRUGGLE MARY ZIEGLER ABSTRACT Why, in the face of ongoing criticism, do advocates of same-sex marriage continue to pursue litigation? Recently, Perry v. Schwarzenegger, a challenge to California’s ban on same-sex marriage, and Gill v. Office of Personnel Management, a lawsuit challenging section three of the federal Defense of Marriage Act, have created divisive debate. Leading scholarship and commentary on the litigation of decisions like Perry and Gill have been strongly critical, predicting that it will produce a backlash that will undermine the same- sex marriage cause. These studies all rely on a particular historical account of past same-sex marriage decisions and their effect on political debate. -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

The Settlement Agreement And

T Y i a 1 EXANDER MORRISON FEHRLLP ichael S Morrison State Bar No 205320 Su c u rv i o tv 2 F k i fi 00 Avenue of the Stars SUlte 9 C iP a Y s at r 5 s 4 F a a E c r s Angeles lifornia 90067 3 310 394 088 F 310 394 08ll Q 1 C 4 mmorrison com a ry amfllp f B 5 i J s R L C3P JT orneys for aintiffs individually on behalf g all others si ilarly situated and the general i lic 7 SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA 8 COUNTY OF SAN BERNARDINO j 9 TTINA BO ALL an Individual PALOMA Case No CIVDS2010984 QUIVEL Individual ANGEL 10 GS a Individual ANGELA Assigned for All Purposes to the Hon David MISON an dividual E GREGORY Cohn 11 TON a Individual and B J Department 5 26 RHLJNE a I individual on behalf of 2 mselves an all others similarly situated Filed June 4 2020 13 Complaint Plaintiffs REVISED ORDER RE 14 PLAI TIFFS MOTION FOR PRE IMINARY AND 15 CON ITIONAL APPROVAL OF I II CLA S ACTION SETTLEMENT 16 S ANGEL S TIMES COMMUNICATIONS r C a Delaw e limited liability company DAT September 9 2020 17 BL7NE PU LISHING COMPANY TIME 10 00 am rmerly doin business as TRONC INC a PLAC Dept 5 26 18 laware corp ration and DOES 1 through 0 inclusive 19 I Defendants 20 I 21 j I C 22 w 23 a 24 r 25 26 I I I 27 2 I i i II PROPOS REVISED ORDER RE MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY APPROVAL OF CLASS ACTION SETTLEMENT i i I 1 [PROPOSED] ORDER 2 3 WHEREAS, the representatives BETTINA BOXALL, PALOMA ESQUIVEL, ANGELA 4 JENNINGS, ANGELA JAMISON, GREGORY BRAXTON, and B.J. -

Office of Public Information

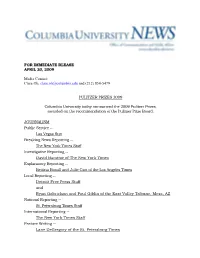

FOR IMMEDIATE RLEASE APRIL 20, 2009 Media Contact: Clare Oh, [email protected] and (212) 854-5479 PULITZER PRIZES 2009 Columbia University today announced the 2009 Pulitzer Prizes, awarded on the recommendation of the Pulitzer Prize Board. JOURNALISM Public Service -- Las Vegas Sun Breaking News Reporting -- The New York Times Staff Investigative Reporting -- David Barstow of The New York Times Explanatory Reporting -- Bettina Boxall and Julie Cart of the Los Angeles Times Local Reporting -- Detroit Free Press Staff and Ryan Gabrielson and Paul Giblin of the East Valley Tribune, Mesa, AZ National Reporting -- St. Petersburg Times Staff International Reporting -- The New York Times Staff Feature Writing -- Lane DeGregory of the St. Petersburg Times Commentary -- Eugene Robinson of The Washington Post Criticism -- Holland Cotter of The New York Times Editorial Writing -- Mark Mahoney of The Post-Star, Glens Falls, NY Editorial Cartooning -- Steve Breen of The San Diego Union-Tribune Breaking News Photography -- Patrick Farrell of The Miami Herald Feature Photography -- Damon Winter of The New York Times LETTERS AND DRAMA Fiction -- Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout (Random House) Drama -- Ruined by Lynn Nottage History -- The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family by Annette Gordon- Reed (W.W. Norton & Company) Biography -- American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House by Jon Meacham (Random House) Poetry -- The Shadow of Sirius by W. S. Merwin (Copper Canyon Press) General Nonfiction -- Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II by Douglas A. Blackmon (Doubleday) MUSIC Double Sextet by Steve Reich, premiered March 26, 2008 in Richmond, VA (Boosey & Hawkes). -

Volume 68 Issue 2

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY ANNUAL SURVEY OF AMERICAN LAW VOLUME 68 ISSUE 2 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW ARTHUR T. VANDERBILT HALL Washington Square New York City Imaged with the Permission of N.Y.U. Annual Survey of American Law New York University Annual Survey of American Law is in its seventy-first year of publication. L.C. Cat. Card No.: 46-30523 ISSN 0066-4413 All Rights Reserved New York University Annual Survey ofAmerican Law is published quarterly at 110 West 3rd Street, New York, New York 10012. Subscription price: $30.00 per year (plus $4.00 for foreign mailing). Single issues are available at $16.00 per issue (plus $1.00 for foreign mailing). For regular subscriptions or single issues, contact the Annual Survey editorial office. Back issues may be ordered directly from William S. Hein & Co., Inc., by mail (1285 Main St., Buffalo, NY 14209-1987), phone (800- 828-7571), fax (716-883-8100), or email ([email protected]). Back issues are also available in PDF format through HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org). All articles copyright @ 2012 by the New York University Annual Survey of American Law, except when otherwise expressly indicated. For permission to reprint an article or any portion thereof, please address your written request to the New York University Annual Survey of American Law. Copyright: Except as otherwise provided, the author of each article in this issue has granted permission for copies of that article to be made for classroom use, provided that: (1) copies are distributed to students at or below cost; (2) the author and journal are identified on each copy; and (3) proper notice of copyright is affixed to each copy. -

1997-1998 Supreme Court Preview: Contents Institute of Bill of Rights Law at the William & Mary Law School

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Supreme Court Preview Conferences, Events, and Lectures 1997 1997-1998 Supreme Court Preview: Contents Institute of Bill of Rights Law at the William & Mary Law School Repository Citation Institute of Bill of Rights Law at the William & Mary Law School, "1997-1998 Supreme Court Preview: Contents" (1997). Supreme Court Preview. 73. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/preview/73 Copyright c 1997 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/preview A AMIL 'g. Ik Ilk I w 'am isms 1997-98 Supreme Court Preview SUMMARY OF CONTENTS Conference Schedule iv Panelists vi Acknowledgments xi The Institute of Bill of Rights Law xvii Table of Contents xix iii 1997-98 Supreme Court Preview CONFERENCE SCHEDULE Friday, October 24 5:30 pm -- 6:15 pm Registration Lobby, Law School 6:15 pm -- 6:20 pm Welcome McGlothlin Moot Court Room 6:20 pm -- 7:40 pm MOOT COURT ARGUMENT McGlothlin Moot Court Room Piscataway v. Taxman, No. 96-679 Advocates: Samuel Issacharoff Suzanna Sherry Court: Joan Biskupic, Chief Justice Richard Carelli Lyle Denniston Aaron Epstein Edward Felsenthal Susan Grover Tony Mauro David Savage Margaret Spencer 7:50 pm -- 8:10 pm The View from the Solicitor McGlothlin Moot Court Room General's Office Walter Dellinger 8:10 pm -- 9:00 pm The Court and Race Relations: McGlothlin Moot Court Room What Lies Ahead? Moderator: Steve Wermiel Panel: Neal Devins Sam Issacharoff David -

Beyond Sexual Orientation in Queer Legal Theory

Denver Law Review Volume 75 Issue 4 Symposium - InterSEXionality: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Queering Article 13 Legal Theory January 2021 Beyond Sexual Orientation in Queer Legal Theory: Majoritarianism, Multidimensionality, and Responsibility in Social Justice Scholarship or Legal Scholars as Cultural Warriors Francisco Valdes Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/dlr Recommended Citation Francisco Valdes, Beyond Sexual Orientation in Queer Legal Theory: Majoritarianism, Multidimensionality, and Responsibility in Social Justice Scholarship or Legal Scholars as Cultural Warriors, 75 Denv. U. L. Rev. 1409 (1998). This Back Matter is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Denver Sturm College of Law at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. AFTERWORD BEYOND SEXUAL ORIENTATION IN QUEER LEGAL THEORY: MAJORITARIANISM, MULTIDIMENSIONALITY, AND RESPONSIBILITY IN SOCIAL JUSTICE SCHOLARSHIP OR LEGAL SCHOLARS AS CULTURAL WARRIORS FRANCISCO VALDES* Introduction .......................................................................................................... 14 10 A. Sexual Minorities & Sexual Orientation Scholarship Since 1979 .............. 1416 B. Sexual Orientation, Critical Race Theory & Postmodem Analysis ............ 1418 C. Queering Sexual Orientation Legal Scholarship ........................................ -

Conservative Environmental Thought: the Bush Administration And

Conservative Environmental Thought: The Bush Administration and Environmental Policy Barton H. Thompson, Jr.* I. Conservative Perspectives on Environmental Policy .................... 312 A . L ibertarians ................................................................................ 314 B . Pareto O ptim ists ........................................................................ 317 C. Jeffersonian Conservatives ....................................................... 319 D . H am iltonian Conservatives ...................................................... 320 E. Burkean Conservatives ............................................................. 322 II. Bush A dm inistration Policies .......................................................... 323 A . Subsidy R eform ......................................................................... 325 B. Inform ation D isclosure ............................................................. 331 C. Econom ic Incentives ................................................................. 335 D . M arket M echanism s .................................................................. 339 E . Federalism .................................................................................. 344 III. C onclusion ......................................................................................... 346 Republican Presidents over the last forty years have often produced environmental advances, although not always out of environmental sympathies! Nudged by the prospect of a tough reelection battle with Senator -

Curing Wildfire Law at the Font of Oil and Gas Regulation*

DARLING.TOPRINTER (DO NOT DELETE) 5/17/2018 8:31 PM A Baptism by Incentives: Curing Wildfire Law at the Font of Oil and Gas Regulation* For over sixty years, wildland fires in the United States have been consuming American land to an ever-increasing extent:1 from January 1 through March 31 of 2017 alone, over two million acres of U.S. earth were scorched by wildfires.2 According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, nine out of the ten years with the highest burned acreage counts on record in the United States have occurred within the past seventeen years.3 The cost of residential property destruction, both in terms of quantity and in terms of value, is one significant marker of just the human costs of wildfires. From 2002 to 2011, insured losses4 related to wildfire totaled $7.9 billion, up 364.7% from the previous decade’s total insured losses.5 On at least one rendering, annual American property loss due to wildfire has been estimated to have increased by more than 22,000% between 1960 and the * Deepest gratitude to Professor Jane Cohen for her guidance in structuring and shaping this Note, as well as securing a class visit from the individual whose work inspired it—Professor Karen Bradshaw of Arizona State University. I would also like to thank my family and friends for their tireless support throughout my law school career. Finally, my gratitude goes out to the Texas Law Review members, whose impeccable work has rendered any errors mine alone. 1. See Total Wildland Fires and Acres (1960-2015), NAT’L INTERAGENCY FIRE CTR., https://www.nifc.gov/fireInfo/fireInfo_stats_totalFires.html [https://perma.cc/5WNK-9HAL] (reporting increasing rates of acreage burned by American wildfires); see also Climate Change Indicators: Wildfires, U.S. -

Bill Clinton Bibliography - 2002 Thru 2020*

Bill Clinton Bibliography - 2002 thru 2020* Books African American Journalists Rugged Waters: Black Journalists Swim the Mainstream by Wayne Dawkins PN4882.5 .D38 2003 African American Women Cotton Field of Dreams: A Memoir by Janis Kearney F415.3.K43 K43 2004 For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Politics by Donna Brazile E185.96 .B829 2018 African Americans--Biography Step by Step: A Memoir of Hope, Friendship, Perseverance, and Living the American Dream by Bertie Bowman E185.97 .B78 A3 2008 African Americans--Civil Rights Brown Versus Board of Education: Caste, Culture, and the Constitution KF4155 .B758 2003 A Matter of Justice: Eisenhower and the Beginning of the Civil Rights Revolution by David Nichols E836 .N53 2007 Winning While Losing: Civil Rights, the Conservative Movement, and the Presidency From Nixon to Obama edited by Kenneth Osgood and Derrick White E185.615 .W547 2013 African Americans--Politics and Government Bill Clinton and Black America by DeWayne Wickham E886.2 .W53 2002 Conversations: William Jefferson Clinton from Hope to Harlem by Janis Kearney E886.2 .K43 2006 African Americans--Social Conditions The Mark of Criminality: Rhetoric, Race, and Gangsta Rap in the War-on-crime Era * This is a non-annotated continuation of Allan Metz’s, Bill Clinton: A Bibliography. 1 by Bryan McCann ML3531 .M3 2019 Air Force One (Presidential Aircraft) Air Force One: The Aircraft that Shaped the Modern Presidency by Von Hardesty TL723 .H37 2003 Air Force One: A History of the Presidents and Their Planes by Kenneth Walsh TL723 .W35