Conservative Environmental Thought: the Bush Administration And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greenspace | Los

NOAA may prohibit Navy sonar testing at marine mammal 'hot spots' | Greenspace | Los ... Page 1 of 3 Subscribe Place An Ad Jobs Cars Real Estate Rentals Foreclosures More Classifieds ENVIRONMENT LOCAL U.S. & WORLD BUSINESS SPORTS ENTERTAINMENT HEALTH LIVING TRAVEL OPINION MORE Search GO L.A. NOW POLITICS CRIME EDUCATION O.C. WESTSIDE NEIGHBORHOODS ENVIRONMENT OBITUARIES HOT LIST Stay connected: Greenspace ENVIRONMENTAL NEWS FROM CALIFORNIA AND BEYOND advertisement « Previous Post | Greenspace Home NOAA may prohibit Navy sonar testing at marine mammal 'hot spots' January 22, 2010 | 2:49 pm Marine mammal "hot spots" in areas including Southern California's coastal waters may become off limits to testing of a type of Navy sonar linked to the deaths of whales under a plan announced this week by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. NOAA also called for development of a system for estimating the "comprehensive sound budget for the oceans," which could help reduce human sources of noise -- vessel traffic, sonar and construction activities -- that degrade the environment in which sound-sensitive species communicate. The plans were revealed in a letter from NOAA Administrator Jane Lubchenco to the White House Council on Environmental Quality. In the letter, Lubchenco said her goal is to reduce adverse effects on marine mammals resulting from the Navy's training exercises. About the Bloggers Environmentalists contend that sonar has a possibly deafening effect on marine mammals. Studies around the world have shown the piercing underwater sounds cause whales to flee in panic or to dive Bettina Boxall too deeply. Whales have been found beached in Greece, the Canary Islands and the Bahamas after Susan Carpenter Tiffany Hsu sonar was used in the area. -

Beyond Drought: Water Rights in the Age of Permanent Depletion

Beyond Drought: Water Rights in the Age of Permanent Depletion Burke W. Griggs* INTRODUCTION Drought affects more North Americans than any other natural hazard.1 Over the past two decades, it has returned to the American West with historic intensity. The long drought of 2000–06 across the Great Plains resulted in record low stream flows and record low reservoir levels; in Kansas, it compelled a record number of surface water rights curtailments.2 The Colorado River Basin is caught in the throes of a fifteen-year drought that has reduced water levels in the two largest reservoirs in the United States, Lake Mead and Lake Powell, to unprecedented lows.3 California is experiencing its worst drought since 1976–77, and possibly since 1580.4 Chronic water shortages have driven at least ten states to litigation presently before the Supreme Court of the United States, and most of these cases involve western waters.5 Unlike the Dust Bowl era, when Farm Security Administration photographs of dry streambeds and drought-stricken fields * Consulting Professor, Bill Lane Center for the American West, Stanford University; Special Assistant Attorney General, State of Kansas. 1. Kansas Drought Watch, U.S.GEOLOGICAL SURVEY, http://ks.water.usgs.gov/ks-drought (last visited May 13, 2014). 2. Id. 3. Michael Wines, Colorado River Drought Forces a Painful Reckoning for States, N.Y. TIMES, Jan. 5, 2014, at A1; Felicity Barringer, Lake Mead Hits Record Low Level, N.Y. TIMES, (Oct. 18, 2010, 2:05 PM), http://green.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/10/18/lake-mead-hits-record-low-level. -

Litigation, Argumentative Strategies, and Coalitions in the Same-Sex Marriage Struggle

Florida State University College of Law Scholarship Repository Scholarly Publications Winter 2012 The Terms of the Debate: Litigation, Argumentative Strategies, and Coalitions in the Same-Sex Marriage Struggle Mary Ziegler Florida State University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/articles Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, and the Litigation Commons Recommended Citation Mary Ziegler, The Terms of the Debate: Litigation, Argumentative Strategies, and Coalitions in the Same- Sex Marriage Struggle, 39 FLA. ST. U. L. REV. 467 (2012), Available at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/articles/332 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE TERMS OF THE DEBATE: LITIGATION, ARGUMENTATIVE STRATEGIES, AND COALITIONS IN THE SAME-SEX MARRIAGE STRUGGLE MARY ZIEGLER ABSTRACT Why, in the face of ongoing criticism, do advocates of same-sex marriage continue to pursue litigation? Recently, Perry v. Schwarzenegger, a challenge to California’s ban on same-sex marriage, and Gill v. Office of Personnel Management, a lawsuit challenging section three of the federal Defense of Marriage Act, have created divisive debate. Leading scholarship and commentary on the litigation of decisions like Perry and Gill have been strongly critical, predicting that it will produce a backlash that will undermine the same- sex marriage cause. These studies all rely on a particular historical account of past same-sex marriage decisions and their effect on political debate. -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

December 2020 Edition

The Search for Brave Candidates While many people in the party were thrilled about having a by Amber Jewell candidate like Jo Jorgensen, many others were extremely disappointed. They believed her to be a cookie cutter Libertarians often candidate, put into place as a safe option – and several ridicule those who believed that she wasn’t even the best option with which to support the two-party play it safe. On the flip side, her running mate Spike Cohen system. They strongly was seen as a force to be reckoned with. His presence showed oppose the idea of a certain amount of strength through his passion and choosing “the lesser of communication that made him a great candidate. two evils” and use the oppositional argument As a third party, Libertarians have to work harder than the old against everyone who parties in order to be taken seriously. This has created a claims that a binary challenge in choosing candidates. Many candidates want to be choice is the only way. seen as boisterous so that they can draw attention to the LP in For example, in this past an effort to bring in more members. Others may only want to election, most people be “paper candidates,” not actively involved in campaigning, seemed to despise the just to get names on ballots. But choosing a serious candidate choices of Donald that does not reflect that same boring tactics as the Trump and Joe Biden; so, Libertarians tried vehemently to Republicans and Democrats can be tough. remind others that there are other options. -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

March 10-11, 2012, LNC Meeting Minutes

LNC MEETING MINUTES ROSEN CENTRE, ORLANDO, FL MARCH 10-11, 2012 CURRENT STATUS: AUTO-APPROVED APRIL 7, 2012 VERSION LAST UPDATED: MARCH 17, 2012 LEGEND: text to be inserted - text to be deleted CALL TO ORDER The meeting was called to order at 9:14am at the Rosen Centre in Orlando, Florida. ATTENDANCE Attending the meeting were: Officers: Mark Hinkle (Chair), Mark Rutherford (Vice-Chair), Alicia Mattson (Secretary), Bill Redpath (Treasurer) At-Large Representatives: Kevin Knedler, Wayne Allyn Root, Mary Ruwart, Rebecca Sink-Burris Regional Representatives: Doug Craig (Region 1), Stewart Flood (Region 1), Dan Wiener (Region 1), Vicki Kirkland (Region 2), Andy Wolf (Region 3), Norm Olsen (Region 4), Jim Lark (Region 5S), Dianna Visek (Region 6) Regional Alternates: Scott Lieberman (Region 1), Brad Ploeger (Region 1), David Blau (Region 2), Brett Pojunis (Region 4), Audrey Capozzi (Region 5N) Randy Eshelman (At-Large) and Dan Karlan (Region 5N) were not present. LNC Counsel Gary Sinawski was not present, but did participate by phone in Executive Session. Staff present included Executive Director Carla Howell and Operations Director Robert Kraus. LNC Minutes – Orlando, FL – March 10-11, 2012 Page 1 The gallery contained numerous other attendees including, but not limited to: Lynn House (FL), Chuck House (FL), Joey Kidd (GA), John Wayne Smith (FL), Aaron Starr (CA), Chad Monnin (OH), Aaron Harris (OH), Steve LaBianca (FL) CREDENTIALS Since the previous LNC session, the following events have occurred with regard to LNC credentials: • On December 21, Region 5N notified the LNC Secretary that Audrey Capozzi had been selected to serve as their regional alternate, filling the vacancy created when Carl Vassar resigned. -

University of Texas / Texas Tribune Texas Statewide Survey — (Partial for Day 1)

University of Texas / Texas Tribune Texas Statewide Survey — (partial for Day 1) Field dates: October 11-18, 2010 N=800 Adults; Margin of error=+/-3.46 *Due to rounding, not all percentages sum to 100 Interest and Engagement Q1. Are you registered to vote in the state of Texas? 1. Yes, registered 100% 2. No, not registered 0% 3. Don’t know 0% Q2. Generally speaking, would you say that you are extremely interested in politics and public affairs, somewhat interested, not very interested, or not interested at all? 1. Extremely interested 53% 2. Somewhat interested 36% 3. Not very interested 9% 4. Not at all interested 2% 5. Don’t know 1% Q3. Thinking back over the past 3-4 years, how often would you say that you have voted in local, state, or national elections? 1. Every time 43% 2. Almost every time 31% 3. Some of the time 12% 4. Once or twice 9% 5. Never 4% 6. Don’t know 1% Q4. How closely would you say you have been following the campaign for governor of Texas this year? 1. Extremely closely 34% 2. Somewhat closely 18% 3. Not very closely 13% 4. Not at all 6% 5. Don’t know 1% UT-Austin/Texas Tribune – Texas Statewide Survey, Sept. 2010 Page 1 of 12 Retrospective Assessments Q7. How would you rate the job Barack Obama has done as president? Would you say that you… 1. Approve strongly 14% 2. Approve somewhat 21% 3. Neither approve nor disapprove 4% 4. Disapprove somewhat 6% 5. Disapprove strongly 53% 6. -

The Settlement Agreement And

T Y i a 1 EXANDER MORRISON FEHRLLP ichael S Morrison State Bar No 205320 Su c u rv i o tv 2 F k i fi 00 Avenue of the Stars SUlte 9 C iP a Y s at r 5 s 4 F a a E c r s Angeles lifornia 90067 3 310 394 088 F 310 394 08ll Q 1 C 4 mmorrison com a ry amfllp f B 5 i J s R L C3P JT orneys for aintiffs individually on behalf g all others si ilarly situated and the general i lic 7 SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA 8 COUNTY OF SAN BERNARDINO j 9 TTINA BO ALL an Individual PALOMA Case No CIVDS2010984 QUIVEL Individual ANGEL 10 GS a Individual ANGELA Assigned for All Purposes to the Hon David MISON an dividual E GREGORY Cohn 11 TON a Individual and B J Department 5 26 RHLJNE a I individual on behalf of 2 mselves an all others similarly situated Filed June 4 2020 13 Complaint Plaintiffs REVISED ORDER RE 14 PLAI TIFFS MOTION FOR PRE IMINARY AND 15 CON ITIONAL APPROVAL OF I II CLA S ACTION SETTLEMENT 16 S ANGEL S TIMES COMMUNICATIONS r C a Delaw e limited liability company DAT September 9 2020 17 BL7NE PU LISHING COMPANY TIME 10 00 am rmerly doin business as TRONC INC a PLAC Dept 5 26 18 laware corp ration and DOES 1 through 0 inclusive 19 I Defendants 20 I 21 j I C 22 w 23 a 24 r 25 26 I I I 27 2 I i i II PROPOS REVISED ORDER RE MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY APPROVAL OF CLASS ACTION SETTLEMENT i i I 1 [PROPOSED] ORDER 2 3 WHEREAS, the representatives BETTINA BOXALL, PALOMA ESQUIVEL, ANGELA 4 JENNINGS, ANGELA JAMISON, GREGORY BRAXTON, and B.J. -

December 6-7, 2008, LNC Meeting Minutes

LNC Meeting Minutes, December 6-7, 2008, San Diego, CA To: Libertarian National Committee From: Bob Sullentrup CC: Robert Kraus Date: 12/7/2008 Current Status: Automatically Approved Version last updated December 31, 2008 These minutes due out in 30 days: January 6, 2008 Dates below may be superseded by mail ballot: LNC comments due in 45 days: January 21, 2008 Revision released (latest) 14 days prior: February 14, 2009 Barring objection, minutes official 10 days prior: February 18, 2009 * Automatic approval dates relative to February 28 Charleston meeting The meeting commenced at 8:12am on December 6, 2008. Intervening Mail Ballots LNC mail ballots since the last meeting in DC included: • Sent 9/10/2008. Moved, that the tape of any and all recordings of the LNC meeting of Sept 6 & 7, 2008 be preserved until such time as we determine, by a majority vote of the Committee, that they are no longer necessary. Co-Sponsors Rachel Hawkridge, Dan Karlan, Stewart Flood, Lee Wrights, Julie Fox, Mary Ruwart. Passed 13-1, 3 abstentions. o Voting in favor: Michael Jingozian, Bob Sullentrup, Michael Colley, Lee Wrights, Mary Ruwart, Tony Ryan, Mark Hinkle Rebecca Sink-Burris, Stewart Flood, Dan Karlan, James Lark, Julie Fox, Rachel Hawkridge o Opposed: Aaron Starr o Abstaining: Bill Redpath, Pat Dixon, Angela Keaton Moment of Reflection Chair Bill Redpath called for a moment of reflection, a practice at LNC meetings. Opportunity for Public Comment Kevin Takenaga (CA) welcomed the LNC to San Diego. Andy Jacobs (CA) asked why 2000 ballot access signatures were directed to be burned by the LP Political Director in violation of election law? Mr. -

Office of Public Information

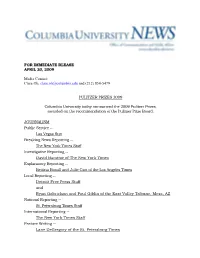

FOR IMMEDIATE RLEASE APRIL 20, 2009 Media Contact: Clare Oh, [email protected] and (212) 854-5479 PULITZER PRIZES 2009 Columbia University today announced the 2009 Pulitzer Prizes, awarded on the recommendation of the Pulitzer Prize Board. JOURNALISM Public Service -- Las Vegas Sun Breaking News Reporting -- The New York Times Staff Investigative Reporting -- David Barstow of The New York Times Explanatory Reporting -- Bettina Boxall and Julie Cart of the Los Angeles Times Local Reporting -- Detroit Free Press Staff and Ryan Gabrielson and Paul Giblin of the East Valley Tribune, Mesa, AZ National Reporting -- St. Petersburg Times Staff International Reporting -- The New York Times Staff Feature Writing -- Lane DeGregory of the St. Petersburg Times Commentary -- Eugene Robinson of The Washington Post Criticism -- Holland Cotter of The New York Times Editorial Writing -- Mark Mahoney of The Post-Star, Glens Falls, NY Editorial Cartooning -- Steve Breen of The San Diego Union-Tribune Breaking News Photography -- Patrick Farrell of The Miami Herald Feature Photography -- Damon Winter of The New York Times LETTERS AND DRAMA Fiction -- Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout (Random House) Drama -- Ruined by Lynn Nottage History -- The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family by Annette Gordon- Reed (W.W. Norton & Company) Biography -- American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House by Jon Meacham (Random House) Poetry -- The Shadow of Sirius by W. S. Merwin (Copper Canyon Press) General Nonfiction -- Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II by Douglas A. Blackmon (Doubleday) MUSIC Double Sextet by Steve Reich, premiered March 26, 2008 in Richmond, VA (Boosey & Hawkes). -

4. Chapter 3.Wps

Chapter Three State Policies That Promote Corporate Size and Centralization Capitalism, if we take it in R.A. Wilson's sense of a political and economic system in which the state intervenes in the market on behalf of capitalists, has been exploitative since the beginning. It was established at the outset by massive acts of state robbery and restrictions on liberty: the so-called "primitive accumulation" by which the peasantry's property in the land was expropriated, the Laws of Settlement which acted as an internal passport system restricting movement of the working class, the Combination Laws which restricted the bargaining power of labor, and the mercantilism and imperial aggression by which the so- called world market was created. These matters fall too far outside of our focus for detailed examination. A summary of all the uses of force involved in the establishment of capitalism can be found in Chapter Four of Studies in Mutualist Political Economy.1 Once established on this basis, the system was maintained through various state- enforced legal privileges. This, also, is too far outside the scope of the present chapter to examine in depth. The main forms of privilege that existed before the rise of corporate capitalism in the nineteenth century were the "Four Monopolies" summarized by Benjamin Tucker in "State Socialism and Anarchism," and will be considered in greater depth in our examination of privilege in Chapter Eleven. Our main concern here is not with this earlier system of privilege, but more specifically with the state's later role in the creation and development of the corporate economy, the concentration of capital, and the centralization of production.