Toussaint Charbonneau, a Most Durable Man

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mountain Man Clymer Museum of Art It Has Been Said That It Took Rugged, Practically Fearless Individuals to Explore and Settle America’S West

HHiiSSTORTORYY— PaSt aNd PerspeCtive John Colter encountering some Indians The First Mountain Man Clymer Museum of Art It has been said that it took rugged, practically fearless individuals to explore and settle America’s West. Surely few would live up to such a characterization as well as John Colter. by Charles Scaliger ran, and sharp stones gouged the soles of wether Lewis traveled down the Ohio his feet, but he paid the pain no mind; any River recruiting men for his Corps of Dis- he sinewy, bearded man raced up torment was preferable to what the Black- covery, which was about to strike out on the brushy hillside, blood stream- foot warriors would inflict on him if they its fabled journey across the continent to ing from his nose from the terrific captured him again. map and explore. The qualifications for re- Texertion. He did not consider himself a cruits were very specific; enlistees in what In 1808, the year John Colter ran his fast runner, but on this occasion the terror race with the Blackfeet, Western Mon- became known as the Lewis and Clark of sudden and agonizing death lent wings tana had been seen by only a handful of expedition had to be “good hunter[s], to his feet. Somewhere not far behind, his white men. The better-known era of the stout, healthy, unmarried, accustomed to pursuers, their lean bodies more accus- Old West, with its gunfighters, cattlemen, the woods, and capable of bearing bodily tomed than his to the severe terrain, were and mining towns, lay decades in the fu- fatigue in a pretty considerable degree.” closing in, determined to avenge the death ture. -

History of Navigation on the Yellowstone River

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1950 History of navigation on the Yellowstone River John Gordon MacDonald The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation MacDonald, John Gordon, "History of navigation on the Yellowstone River" (1950). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2565. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2565 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HISTORY of NAVIGATION ON THE YELLOWoTGriE RIVER by John G, ^acUonald______ Ë.À., Jamestown College, 1937 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Mas ter of Arts. Montana State University 1950 Approved: Q cxajJL 0. Chaiinmaban of Board of Examiners auaue ocnool UMI Number: EP36086 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Ois8<irtatk>n PuUishing UMI EP36086 Published by ProQuest LLC (2012). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

THE CHALLENGE to COMMUNICATE at Fort Mandan in North Dakota, Their Interpreters Were Two Frenchmen Who Had Been Living with the Introduction Indians

THE CHALLENGE TO COMMUNICATE At Fort Mandan in North Dakota, their interpreters were two Frenchmen who had been living with the Introduction Indians. They hired Touissant Charbonneau and one of his Shoshone wives to interpret for them when they met the Shoshones. The Hidatsa call her When Lewis and Clark embarked upon their epic Sakakawea, or Bird Woman and the Shoshones call journey in 1804, they knew very little about the her Sacagawea. people they would encounter along the Missouri River. Even less was known about the tribes of the Charles McKenzie was a Canadian trader who Columbia. The explorers had no idea of how or by observed the Lewis and Clark expedition in the what means those people would communicate. Mandan Country in the spring of 1805. He describes them below: With the help of interpreters, they were sometimes able to effectively exchange information with the The woman who answered the purpose of wife to tribes along the way. However, there were many Charbonneau, was of the Serpent Nation and lately times when their interpreters were not able to help taken prisoner by a war party:- She understood a them. Often they had to rely on other methods of little Gros Ventres, in which she had to converse communication, such as sign language and drawing. with her husband, who was a Canadian, and who did not understand English- A Mulatto, who spoke Communication Challenges for the Expedition bad French and worse English served as interpreter to the Captains- So that a single word to be Communication was generally not a problem as the understood by the party required to pass from the party traveled up the Missouri River. -

Foreword & Introduction to the Manuel Lisa's Fort On-The-Yellowstone

Foreword 1873 land surveys for their track location within Montana Territory, and the Department of the Interior’s (General Land & Office / Bureau of Land Management) fully documented location Introduction to the Manuel Lisa’s of the land that is verified as the site upon which Manuel Lisa constructed the fort. That land still exists, the BLM is its Fort on-the-Yellowstone designated manager, and is listed as such by the DOI/GLO/BLM as “Public Use.” Up until the 1950’s it was thought to belong to the Crow Nation. These facts will be explained in the following Throughout the early history of Montana it has been thought that chapters. The definitions of the fort location were buried deep in the intrepid and brilliant entrepreneur ‘Manuel Lisa’, had the historical past; requiring the services of several agencies and constructed the first fur trading post on the Yellowstone River that dedicated people to unearth – what eventually became self evident. was ‘lost in time’ due to changes in the local area’s Montana river topography. In this brief summary of various major research efforts The following irrefutable facts are presented: and the full diligence of the National Park Service and local residents we are disclosing what actually happened to one of the Fact #1 – The original junction point of the Yellowstone greatest achievements in world history – as seen through the eyes and Big Horn Rivers in Montana has not changed of local Montana residents. significantly since 1806. In this volume we will take you through the maze of reputed Fact #2 – The Manuel Lisa Fort, constructed in 1807, was research activities about this very special fort; the first reported located on the south bank of the Yellowstone River on a building constructed upon future Montana soil in 1807. -

Kidnapped and Sold Into Marriage on the Lewis and Clark Expedition

Fact or Fiction? Name: _________________________ Below is a passage on Sacagawea. On the following page is a chart with ten statements. Indicate whether each statement is fact or fiction. Sacagawea was born sometime around 1790. She is best known for her role in assisting the Lewis and Clark expedition. She and her husband were guides from the Great Plains to the Pacific Ocean and back. Kidnapped and Sold into Marriage Sacagawea was kidnapped from her Shoshone village by Hidatsa Indians when she was twelve years old. She was promptly sold into slavery. She was then sold to a French fur trapper by the name of Toussaint Charbonneau. The pair became married and had a son named Jean-Baptiste. On the Lewis and Clark Expedition Although there are conflicting opinions concerning how important Sacagawea was to the Lewis and Clark expedition, she did serve as the interpreter and negotiator to the Shoshone tribe - that was led by her brother Cameahwait. She helped them obtain essential supplies and horses while she carried her infant son on her back. Furthermore, Sacagawea helped identify edible plants and herbs and prevented hostile relations with other tribes simply by being with the expedition. She was even more important on the return trip because she was familiar with the areas in which the expedition was traveling. Lewis and Clark received credit for discovering hundreds of animals and plants that Sacagawea had probably seen for years. Although she received no payment for her help, her husband was rewarded with cash and land. Death and Adoption of her Children Six years after the journey, Sacagawea died after giving birth to her daughter Lisette. -

Fact Sheet #3

Stream Team Academy Fact Sheet #3 LEWIS & CLARK An Educational Series For Stream Teams To Learn and Collect Stream Team Academy Fact Sheet Series 004 marks the bicentennial of the introverted, melancholic, and moody; #1: Tree Planting Guide Lewis and Clark expedition. Clark, extroverted, even-tempered, and 2Meriwether Lewis and his chosen gregarious. The better educated and more #2: Spotlight on the Big companion, William Clark, were given a refined Lewis, who possessed a Muddy very important and challenging task by philosophical, romantic, and speculative President Thomas Jefferson. Lewis was a mind, was at home with abstract ideas; #3: Lewis & Clark long-time friend of Jeffersons and his Clark, of a pragmatic mold, was more of a personal secretary. They shared common practical man of action. Each supplied Watch for more Stream views on many issues but, perhaps most vital qualities which balanced their Team Academy Fact importantly, they both agreed on the partnership. Sheets coming your way importance of exploring the west. The The men and their accompanying soon. Plan to collect the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 made this party were brave and courageous. They entire educational series possible as well as critical for a growing had no way of knowing what they would for future reference! nation to learn about the recently acquired encounter on their journey or if they lands and peoples that lay between the would make it back alive. They set out Mississippi River and a new western with American pride to explore the border. unknown, a difficult task that many times Both Lewis and Clark have been goes against human nature. -

Mandan/ Hidatsa Encounter Packet Unit: Politics & Diplomacy (Elementary and Middle School)

Mandan/ Hidatsa Encounter Packet Unit: Politics & Diplomacy (Elementary and Middle School) To the Cooperative Group: In this packet you will find: 1. a map showing locations of four tribal encounters 2. a short explanation of the Mandan/Hidatsa encounter 3. excerpts from Clark’s journal concerning that encounter 4. four questions for your group to discuss and try to answer Lewis and Clark spend the winter of 1804-1805 in North Dakota near the Mandan and Hidatsa tribes. During this winter the temperature dropped as low as 40 degrees below zero. The Captains had their men build a fort near the Mandan villages, which they named Fort Mandan. That is where they spent the winter, waiting for spring so that they could continue their journey. The Mandan and Hidatsa Indians were well acquainted with white fur traders and knew of many European customs. During the winter of 1804-1805, these Indians visited Fort Mandan almost daily and were helpful in providing food and information to the Americans. It was while they were at Fort Mandan that Lewis and Clark met Charboneau and his wife Sacagawea. It was also here that baby “Pomp” was born. Here is what Captain Clark wrote in his journal about the Mandan/Hidatsa Indians visiting the Corps at Fort Mandan: William Clark, December 31, 1804 “ A number of Indians here every Day our blacksmith mending their axes, hoes etc for which the squaws bring corn for payment.” At the end of their stay, the day before leaving Fort Mandan, Clark wrote: William Clark, Wednesday, March 20, 1805 “I visited the Chief of the Mandans in the Course of the Day and Smoked a pipe with himself and Several old men.” Questions and activities for cooperative group to consider: • find the location of Fort Mandan • how far did the Corps travel from St. -

The Sacagawea Mystique: Her Age, Name, Role and Final Destiny Columbia Magazine, Fall 1999: Vol

History Commentary - The Sacagawea Mystique: Her Age, Name, Role and Final Destiny Columbia Magazine, Fall 1999: Vol. 13, No. 3 By Irving W. Anderson EDITOR'S NOTE The United States Mint has announced the design for a new dollar coin bearing a conceptual likeness of Sacagawea on the front and the American eagle on the back. It will replace and be about the same size as the current Susan B. Anthony dollar but will be colored gold and have an edge distinct from the quarter. Irving W. Anderson has provided this biographical essay on Sacagawea, the Shoshoni Indian woman member of the Lewis and Clark expedition, as background information prefacing the issuance of the new dollar. THE RECORD OF the 1804-06 "Corps of Volunteers on an Expedition of North Western Discovery" (the title Lewis and Clark used) is our nation's "living history" legacy of documented exploration across our fledgling republic's pristine western frontier. It is a story written in inspired spelling and with an urgent sense of purpose by ordinary people who accomplished extraordinary deeds. Unfortunately, much 20th-century secondary literature has created lasting though inaccurate versions of expedition events and the roles of its members. Among the most divergent of these are contributions to the exploring enterprise made by its Shoshoni Indian woman member, Sacagawea, and her destiny afterward. The intent of this text is to correct America's popular but erroneous public image of Sacagawea by relating excerpts of her actual life story as recorded in the writings of her contemporaries, people who actually knew her, two centuries ago. -

American Expansionism, the Great Plains, and the Arikara People, 1823-1957

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2019 Breakdown of Relations: American Expansionism, the Great Plains, and the Arikara People, 1823-1957 Stephen R. Aoun Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, Diplomatic History Commons, Other History Commons, and the United States History Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/5836 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Breakdown of Relations: American Expansionism, the Great Plains, and the Arikara People, 1823-1957 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University By Stephen Robert Aoun Bachelor of Arts, Departments of History and English, Randolph-Macon College, 2017 Director: Professor Gregory D. Smithers, Department of History, College of Humanities and Sciences, Virginia Commonwealth University Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia April 2019 Table of Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Chapter One Western Expansion and Arikara Identity ………………………………………………. 17 Chapter Two Boarding Schools and the Politics of Assimilation ……...……………………………... 37 Chapter Three Renewing Arikara Identity -

Toussaint Charbonneau (1767- C

Toussaint Charbonneau (1767- c. 1839-1843) By William L. Lang Toussaint Charbonneau played a brief role in Oregon’s past as part of the Corps of Discovery, the historic expedition led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark in 1804-1806. He is one of the most recognizable among members of the Corps of Discovery, principally as the husband of Sacagawea and father of Jean-Baptiste Charbonneau, the infant who accompanied the expedition. The captains hired Charbonneau as an interpreter on April 7, 1805, at Fort Mandan in present-day North Dakota and severed his employment on August 17, 1806, on their return journey. Charbonneau was born on March 22, 1767, in Boucherville, Quebec, a present-day suburb of Montreal, to parents Jean-Baptiste Charbonneau and Marguerite Deniau. In his youth, he worked for the North West Company, and by the time Lewis and Clark encountered him in late 1804, he was an independent trader living at a Minnetaree village on the Knife River, a tributary to the Missouri near present-day Stanton, North Dakota. Charbonneau lived in the village with his Shoshoni wife Sacagawea, who had been captured by Hidatsas in present-day Idaho four years earlier and may have been sold to Charbonneau as a slave. On November 4, William Clark wrote in his journal that “a Mr. Chaubonée [Charbonneau], interpreter for the Gros Ventre nation Came to See us…this man wished to hire as an interpreter.” Lewis and Clark made a contract with him, but not with Sacagawea, although it is clear that the captains saw Sacagawea’s great benefit to the expedition, because she could aid them when they traveled through her former homeland. -

Lewis & Clark Timeline

LEWIS & CLARK TIMELINE The following time line provides an overview of the incredible journey of the Lewis & Clark Expedition. Beginning with preparations for the journey in 1803, it highlights the Expedition’s exploration of the west and concludes with its return to St. Louis in 1806. For a more detailed time line, please see www.monticello.org and follow the Lewis & Clark links. 1803 JANUARY 18, 1803 JULY 6, 1803 President Thomas Jefferson sends a secret letter to Lewis stops in Harpers Ferry (in present-day West Virginia) Congress asking for $2,500 to finance an expedition to and purchases supplies and equipment. explore the Missouri River. The funding is approved JULY–AUGUST, 1803 February 28. Lewis spends over a month in Pittsburgh overseeing APRIL–MAY, 1803 construction of a 55-foot keelboat. He and 11 men head Meriwether Lewis is sent to Philadelphia to be tutored down the Ohio River on August 31. by some of the nation’s leading scientists (including OCTOBER 14, 1803 Benjamin Rush, Benjamin Smith Barton, Robert Patterson, and Caspar Wistar). He also purchases supplies that will Lewis arrives at Clarksville, across the Ohio River from be needed on the journey. present-day Louisville, Kentucky, and soon meets up with William Clark. Clark’s African-American slave York JULY 4, 1803 and nine men from Kentucky are added to the party. The United States’s purchase of the 820,000-square mile DECEMBER 8–9, 1803 Louisiana territory from France for $15 million is announced. Lewis leaves Washington the next day. Lewis and Clark arrive in St. -

Idaho: Lewis Clark Byway Guide.Pdf

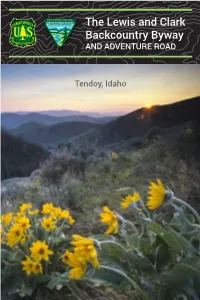

The Lewis and Clark Backcountry Byway AND ADVENTURE ROAD Tendoy, Idaho Meriwether Lewis’s journal entry on August 18, 1805 —American Philosophical Society The Lewis and Clark Back Country Byway AND ADVENTURE ROAD Tendoy, Idaho The Lewis and Clark Back Country Byway and Adventure Road is a 36 mile loop drive through a beautiful and historic landscape on the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail and the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail. The mountains, evergreen forests, high desert canyons, and grassy foothills look much the same today as when the Lewis and Clark Expedition passed through in 1805. THE PUBLIC LANDS CENTER Salmon-Challis National Forest and BLM Salmon Field Office 1206 S. Challis Street / Salmon, ID 83467 / (208)756-5400 BLM/ID/GI-15/006+1220 Getting There The portal to the Byway is Tendoy, Idaho, which is nineteen miles south of Salmon on Idaho Highway 28. From Montana, exit from I-15 at Clark Canyon Reservoir south of Dillon onto Montana Highway 324. Drive west past Grant to an intersection at the Shoshone Ridge Overlook. If you’re pulling a trailer or driving an RV with a passenger vehicle in tow, it would be a good idea to leave your trailer or RV at the overlook, which has plenty of parking, a vault toilet, and interpretive signs. Travel road 3909 west 12 miles to Lemhi Pass. Please respect private property along the road and obey posted speed signs. Salmon, Idaho, and Dillon, Montana, are full- service communities. Limited services are available in Tendoy, Lemhi, and Leadore, Idaho and Grant, Montana.