Book Reviews 1988 COMPILED by GEOFFREY TEMPLEMAN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Touching the Void Discussion Guide

www.influencefilmclub.com Touching the Void Discussion Guide Director: Kevin Macdonald Year: 2003 Time: 106 min You might know this director from: Black Sea (2014) How I Live Now (2013) Marley (2012) The Eagle (2011) Life in a Day (2011) State of Play (2009) My Enemy’s Enemy (2007) The Last King of Scotland (2006) One Day in September (1999) FILM SUMMARY When Joe Simpson published “Touching the Void,” the wildly popular account of his near-death experience on the Siula Grande mountain in the Peruvian Andes, the film rights to the book became a hot commodity. Yet, translating this tale onto the silver screen was a difficult task, one that Academy Award-winning director Kevin Macdonald thought was best suited for the documentary format. “I’m a purist,” Macdonald says. “I don’t like casually blurring the lines of documentary and drama.” So, he stays true to the memoir in his filmic adaptation. Using studio interviews and reenactments, Macdonald tells the thrilling story of Simpson’s climb, bringing us to the top of that treacherous mountain and down again. There was a reason that the West Face of the Siula Grande had never been ascended. It is perilous and menacing at its best. The majority of people would laugh at the prospect, which is exactly the reason Simpson and Yates set out for its peak. Confident young men full of athletic prowess, they alpined to the top, took the victorious photographs, and quickly set out to get back down, all while racing against a ticking clock. The biggest challenge of the journey unexpectedly proved to be the descent. -

TOUCHING the VOID Based on the Book by Joe Simpson Adapted by David Greig

Press Release –Monday 15th July 2019 Fiery Angel and Ambassador Theatre Group Productions present the Bristol Old Vic, Royal Lyceum Theatre Edinburgh, Royal & Derngate, Northampton, and Fuel production of TOUCHING THE VOID Based on the book by Joe Simpson Adapted by David Greig IMAGES CAN BE DOWNLOADED HERE TRAILER CAN BE DOWNLOADED HERE • PRODUCERS ANNOUNCE CASTING FOR THE WEST END TRANSFER OF TOM MORRIS’ PRODUCTION OF TOUCHING THE VOID • THE PRODUCTION WILL OPEN IN PREVIEWS AT THE DUKE OF YORK’S THEATRE ON NOVEMBER 9TH WITH AN OPENING NIGHT OF NOVEMBER 14TH • TICKETS ARE ON SALE NOW Casting has today been announced for Touching The Void. Following critically acclaimed runs at the Bristol Old Vic, Royal & Derngate, Northampton, Royal Lyceum Theatre Edinburgh, Hong Kong Festival and on Tour in the UK Tom Morris’ production of Touching the Void will see original cast members Fiona Hampton, Patrick McNamee and Josh Williams return to the show, joined by Angus Yellowlees. The show will open in the West End at the Duke of York’s Theatre previewing from November 9th for a strictly limited season with an opening night of November 14th. Fiona Hampton will play Sarah. Her theatre credits include: Much Ado About Nothing (Shakespeare’s Globe); Tamburlaine (Yellow Earth/Arcola Theatre and UK tour); A Midsummer Night’s Dream (New Wolsey Theatre); Private Lives (Octagon Theatre/New Victoria Theatre); Winter Hill, The Glass Menagerie, Tull, Of Mice and Men, Lighthearted Intercourse (all Octagon Theatre); Don’t Laugh (Cockpit Theatre); Playhouse Creatures (Chichester Festival Theatre); The Changeling (The Production Works/Southwark Playhouse); Roar, Clockheart Boy (Rose Theatre Kingston); The Merchant of Venice (Derby LIVE). -

Countries and Continents of the World: a Visual Model

Countries and Continents of the World http://geology.com/world/world-map-clickable.gif By STF Members at The Crossroads School Africa Second largest continent on earth (30,065,000 Sq. Km) Most countries of any other continent Home to The Sahara, the largest desert in the world and The Nile, the longest river in the world The Sahara: covers 4,619,260 km2 The Nile: 6695 kilometers long There are over 1000 languages spoken in Africa http://www.ecdc-cari.org/countries/Africa_Map.gif North America Third largest continent on earth (24,256,000 Sq. Km) Composed of 23 countries Most North Americans speak French, Spanish, and English Only continent that has every kind of climate http://www.freeusandworldmaps.com/html/WorldRegions/WorldRegions.html Asia Largest continent in size and population (44,579,000 Sq. Km) Contains 47 countries Contains the world’s largest country, Russia, and the most populous country, China The Great Wall of China is the only man made structure that can be seen from space Home to Mt. Everest (on the border of Tibet and Nepal), the highest point on earth Mt. Everest is 29,028 ft. (8,848 m) tall http://craigwsmall.wordpress.com/2008/11/10/asia/ Europe Second smallest continent in the world (9,938,000 Sq. Km) Home to the smallest country (Vatican City State) There are no deserts in Europe Contains mineral resources: coal, petroleum, natural gas, copper, lead, and tin http://www.knowledgerush.com/wiki_image/b/bf/Europe-large.png Oceania/Australia Smallest continent on earth (7,687,000 Sq. -

Everest and Oxygen—Ruminations by a Climber Anesthesiologist by David Larson, M.D

Everest and Oxygen—Ruminations by a Climber Anesthesiologist By David Larson, M.D. Gaining Altitude and Losing Partial Pressure with Dave and Samantha Larson Dr. Dave Larson is an obstetric anesthesiologist who practices at Long Beach Memorial Medical Center, and his daughter Samantha is a freshman at Stanford University. Together they have successfully ascended the Seven Summits, the tallest peaks on each of the seven continents, a feat of mountaineering postulated in the 1980s by Richard Bass, owner of the Snowbird Ski Resort in Utah. Bass accomplished it first in 1985. Samantha Larson, who scaled Everest in May 2007 (the youngest non-Sherpa to do so) and the Carstensz Pyramid in August 2007, is at age 18 the youngest ever to have achieved this feat. Because of varying definitions of continental borders based upon geography, geology, and geopolitics, there are nine potential summits, but the Seven Summits is based upon the American and Western European model. Reinhold Messner, an Italian mountaineer known for ascending without supplemental oxygen, postulated a list of Seven Summits that replaced a mountain on the Australian mainland (Mount Kosciuszko—2,228 m) with a higher peak in Oceania on New Guinea (the Carstensz Pyramid—4,884 m). The other variation in defining summits is whether you define Mount Blanc (4,808 m) as the highest European peak, or use Mount Elbrus (5,642 m) in the Caucasus. Other summits include Mount Kilimanjaro in Kenya, Africa (5,895 m), Vinson Massif in Antarctica (4,892 m), Mount Everest in Asia (8,848 m), Mount McKinley in Alaska, North America (6,194 m), and Mount Aconcagua in Argentina, South America (6,962 m). -

Slippery Slope

Slippery Slope The film Touching the Void tells the true story of Joe Simpson and Simon Yates and their 1985 attempt to scale Siula Grande. While successful with the ascent, the steep descent they attempted got them in serious trouble. Simpson falls and breaks his leg part-way down the mountain, and Yates attempts to lower him down a particularly dangerous slope by means of a rope since he cannot walk. The slope is inclined at źŴ to the horizontal, and the coefficient of friction between Joe Simpson and the snowfield is ŴŻ. Joe is being held in equilibrium by a rope at an angle of Ź from the slope. Draw a force diagram to show all forces acting on Joe. Assuming Joe (and his kit) weighs ŵŴŴ˫˧ , find the minimum tension in the rope. What is the largest tension that could be applied to the rope? Slippery Slope Solutions The film Touching the Void tells the true story of Joe Simpson and Simon Yates and their 1985 attempt to scale Siula Grande. While successful with the ascent, the steep descent they attempted got them in serious trouble. Simpson falls and breaks his leg part-way down the mountain, and Yates attempts to lower him down a particularly dangerous slope by means of a rope since he cannot walk. The slope is inclined at źŴ to the horizontal, and the coefficient of friction between Joe Simpson and the snowfield is ŴŻ. Joe is being held in equilibrium by a rope at an angle of Ź from the slope. Draw a force diagram to show all forces acting on Joe: Assuming Joe (and his kit) weighs ŵŴŴ ˫˧ , find the minimum tension in the ro pe. -

Stone Mountain State Park

OUR CHANGING LAND Stone Mountain State Park An Environmental Education Learning Experience Designed for Grades 4-8 “The face of places, and their forms decay; And what is solid earth, that once was sea; Seas, in their turn, retreating from the shore, Make solid land, what ocean was before.” - Ovid Metamorphoses, XV “The earth is not finished, but is now being, and will forevermore be remade.” - C.R. Van Hise Renowned geologist, 1898 i Funding for the second edition of this Environmental Education Learning Experience was contributed by: N.C. Division of Land Resources, Department of Environment and Natural Resources, and the N.C. Mining Commission ii This Environmental Education Learning Experience was developed by Larry Trivette Lead Interpretation and Education Ranger Stone Mountain State Park; and Lea J. Beazley, Interpretation and Education Specialist North Carolina State Parks N.C. Division of Parks and Recreation Department of Environment and Natural Resources Michael F. Easley William G. Ross, Jr. Governor Secretary iii Other Contributors . Park volunteers; Carl Merschat, Mark Carter and Tyler Clark, N.C. Geological Survey, Division of Land Resources; Tracy Davis, N.C. Division of Land Resources; The N.C. Department of Public Instruction; The N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources; and the many individuals and agencies who assisted in the review of this publication. 385 copies of this public document were printed at a cost of $2,483.25 or $6.45 per copy Printed on recycled paper. 10-02 iv Table of Contents 1. Introduction • Introduction to the North Carolina State Parks System.......................................... 1.1 • Introduction to Stone Mountain State Park ........................................................... -

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC)

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Summits on the Air USA - Colorado (WØC) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S46.1 Issue number 3.2 Date of issue 15-June-2021 Participation start date 01-May-2010 Authorised Date: 15-June-2021 obo SOTA Management Team Association Manager Matt Schnizer KØMOS Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Page 1 of 11 Document S46.1 V3.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Change Control Date Version Details 01-May-10 1.0 First formal issue of this document 01-Aug-11 2.0 Updated Version including all qualified CO Peaks, North Dakota, and South Dakota Peaks 01-Dec-11 2.1 Corrections to document for consistency between sections. 31-Mar-14 2.2 Convert WØ to WØC for Colorado only Association. Remove South Dakota and North Dakota Regions. Minor grammatical changes. Clarification of SOTA Rule 3.7.3 “Final Access”. Matt Schnizer K0MOS becomes the new W0C Association Manager. 04/30/16 2.3 Updated Disclaimer Updated 2.0 Program Derivation: Changed prominence from 500 ft to 150m (492 ft) Updated 3.0 General information: Added valid FCC license Corrected conversion factor (ft to m) and recalculated all summits 1-Apr-2017 3.0 Acquired new Summit List from ListsofJohn.com: 64 new summits (37 for P500 ft to P150 m change and 27 new) and 3 deletes due to prom corrections. -

1 I-68/I-70: a WINDOW to the APPALACHIANS by Dr. John J

I-68/I-70: A WINDOW TO THE APPALACHIANS by Dr. John J. Renton Dept. of Geology & Geography West Virginia University Morgantown, WV Introduction The Appalachian Mountains are probably the most studied mountains on Earth. Many of our modern ideas as to the origin of major mountain systems evolved from early investigations of the Appalachian region. The Appalachians offer a unique opportunity to experience the various components of an entire mountain system within a relatively short distance and period of time. Compared to the extensive areas occupied by other mountain systems such as the Rockies and the Alps, the Appalachians are relatively narrow and can be easily crossed within a few hours driving time. Following I-68 and I-70 between Morgantown, WV, and Frederick, Maryland, for example, one can visit all of the major structural components within the Appalachians within a distance of about 160 miles. Before I continue, I would like to clarify references to the Allegheny and Appalachian mountains. The Allegheny Mountains were created about 250 million years ago when continents collided during the Alleghenian Orogeny to form the super-continent of Pangea (Figure 1). As the continents collided, a range of mountains were created in much the same fashion that the Himalaya Mountains are now being formed by the collision of India and Asia. About 50 million years after its Figure 1 1 creation, Pangea began to break up with the break occurring parallel to the axis of the original mountains. As the pieces that were to become our present continents moved away from each other, the Indian, Atlantic, and Arctic oceans were created (Figure 2). -

2008. Birds of Conservation Concern 2008

BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN 2008 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Division of Migratory Bird Management Arlington, Virginia December 2008 BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN 2008 Prepared by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Division of Migratory Bird Management Arlington, Virginia Suggested citation: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2008. Birds of Conservation Concern 2008. United States Department of Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Migratory Bird Management, Arlington, Virginia. 85 pp. [Online version available at <http://www.fws.gov/migratorybirds/>] TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS................................................................................................................. i LIST OF ACRONYMS .................................................................................................................. ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................. iv INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................1 BACKGROUND .............................................................................................................................3 Why Did We Create Lists at Different Geographic Scales?................................................3 Bird Conservation Regions (BCRs).........................................................................3 -

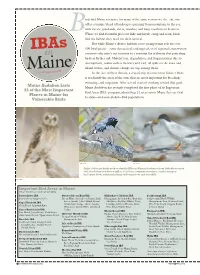

Ibastoryspring08.Pdf

irds find Maine attractive for many of the same reasons we do—the state offers a unique blend of landscapes spanning from mountains to the sea, with forests, grasslands, rivers, marshes, and long coastlines in between. B Where we find beautiful places to hike and kayak, camp and relax, birds find the habitat they need for their survival. But while Maine’s diverse habitats serve an important role for over IBAs 400 bird species—some threatened, endangered, or of regional conservation in concern—the state’s not immune to a growing list of threats that puts these birds at further risk. Habitat loss, degradation, and fragmentation due to development, toxins such as mercury and lead, oil spills on the coast and Maine inland waters, and climate change are top among them. BY ANDREW COLVIN In the face of these threats, a crucial step in conserving Maine’s birds is to identify the areas of the state that are most important for breeding, wintering, and migration. After several years of working toward that goal, Maine Audubon Lists Maine Audubon has recently completed the first phase of its Important 22 of the Most Important Bird Areas (IBA) program, identifying 22 areas across Maine that are vital Places in Maine for Vulnerable Birds to state—and even global—bird populations. HANS TOOM ERIC HYNES Eight of the rare birds used to identify IBAs in Maine (clockwise from left): Short-eared owl, black-throated blue warbler, least tern, common moorhen, scarlet tanager, harlequin duck, saltmarsh sharp-tailed sparrow, and razorbill. MIKE FAHEY Important -

What, Me Worry?

Best of Both Fact and Fiction Texts Best of Both 23.07.08_PRINT.indd 1 23/7/08 17:50:45 Editing and activities by Kate Oliver Cover: Blaise Thompson Chapter title pages: Rebecca Scambler Printed by: Gutenberg Press Published by the English and Media Centre, © 2008 ISBN: 978-1-906101-03-9 Thanks to: Barbara Bleiman, Michael Simons and Lucy Webster for help in finding and selecting the texts. Fran Stowell and Rebecca Scambler for help with the text. Kate Chapman & Alison Boardman, Hornsey School for Girls, Laura Knight, Battersea Technology College, Angharad Ryder Owen, Norbury Business and Enterprise College, Nina Rosenzweig, CEA, Islington for advice on the choice of texts. Penguin Books Ltd for ‘Note to Sixth-Grade Self’ by Julia Orringer from How to Breathe Underwater (2005); ‘Chin Up, My Little Angel – Winning is for Losers’ by Jeremy Clarkson from The World According to Clarkson (2005); The Wylie Agency (UK) Ltd for ‘How the Water Feels to the Fishes’ by Dave Eggers from How the Water Feels to the Fishes (2007); Lucinda Roy and Jean Naggar Literary Agency for ‘Seeing Things in the Dark’ by Lucinda Roy from Go Girl! The Black Woman’s Book of Travel and Adventure, ed Elaine Lees (1999); Barbara Bleiman for ‘A Perfect Afternoon’ (2008); Sebastian Coe and London 2012 for ‘My Heroes Were Olympians’ (2005); Jerome Monahan and Stuart Pearce for ‘The Voice Coach’ (2008); Little Brown for ‘Treasure’s Pocket Money’ by Gina Davidson from Treasure – the Trials of a Teenage Terror (1993, 1996); ‘Tournament’ by Matthew Polly from American Shaolin -

Barber Shop Chronicles

Barber Shop Chronicles A Fuel, National Theatre, and West Yorkshire Playhouse co-production WHEN: VENUE: THURSDAY, NOV 8, 7∶30 PM ROBLE STUDIO THEATER FRIDAY, NOV 9, 7∶30 PM SATURDAY, NOV 10, 2∶30 & 7∶30 PM Photo by Dean Chalkley Program Barber Shop Chronicles A Fuel, National Theatre, and West Yorkshire Playhouse co-production Writer Inua Ellams Design Associate Director Bijan Sheibani Catherine Morgan Designer Rae Smith Re-lighter and Production Electrician Lighting Designer Jack Knowles Rachel Bowen Movement Director Aline David Lighting Associate Sound Designer Gareth Fry Laura Howells Music Director Michael Henry Sound Associate Fight Director Kev McCurdy Laura Hammond Associate Director Stella Odunlami Wardrobe Supervisor Associate Director Leian John-Baptiste Louise Marchand-Paris Assistant Choreographer Kwami Odoom Barber Consultant Peter Atakpo Company Voice Work Charmian Hoare Pre-Production Manager Dialect Coach Hazel Holder Richard Eustace Tour Casting Director Lotte Hines Production Manager Sarah Cowan Wallace / Timothy / Mohammed / Tinashe Tuwaine Barrett Company Stage Manager Tanaka / Fifi Mohammed Mansaray Julia Reid Musa / Andile / Mensah Maynard Eziashi Deputy Stage Manager Ethan Alhaji Fofana Fiona Bardsley Samuel Elliot Edusah Assistant Stage Manager Winston / Shoni Solomon Israel Sylvia Darkwa-Ohemeng Tokunbo / Paul / Simphiwe Patrice Naiambana Costume Supervisor Emmanuel Anthony Ofoegbu Lydia Crimp Kwame / Fabrice / Brian Kenneth Omole Costume and Buying Supervisor Olawale / Wole / Kwabena / Simon Ekow Quartey Jessica Dixon Elnathan / Benjamin / Dwain Jo Servi Abram / Ohene / Sizwe David Webber Co-commissioned by Fuel and the National Theatre. Development funded by Arts Council England with the support of Fuel, National Theatre, West Yorkshire Playhouse, The Binks Trust, British Council ZA, Òran Mór and A Play, a Pie and a Pint.