Phot Son of Bario.Cdr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bab 3 KONFLIK DUNIA DAN PENDUDUKAN JEPUN DI NEGARA KITA 3.1 Nasionalisme Di Negara Kita Sebelum Perang Dunia British Berusaha U

Bab 3 KONFLIK DUNIA DAN PENDUDUKAN JEPUN DI NEGARA KITA 3.1 Nasionalisme di Negara Kita Sebelum Perang Dunia Kesedaran Awal Nasionalisme British berusaha untuk membendung pengaruh idea gerakan Islam. Dengan persetujuan Raja-raja Melayu, British memperkenalkan Enakmen Undang-Undang Islam 1904. Sesiapa yang mencetak dan mengedarkan tulisan berkaitan dengan agama dan politik Islam tanpa keizinan sultan boleh dikenakan hukuman penjara. Memperkenalkan dua badan penyiasat Jabatan Siasatan Jenayah Biro Siasatan Politik 1 2 (Criminal Intelligence Department) (Political Intelligence Bureau) Mengawal gerakan lslah Islamiah Penentangan Tok Janggut merupakan hasil daripada kesedaran politik antarabangsa yang berkaitan Pan-Islamisme. Walaupun hanya melibatkan penduduk Pasir Puteh, isu penentangan adalah untuk mempertahankan agama Islam dan hak penduduk tempatan berlaku di tengah-tengah kancah pergolakan politik yang berlaku di Eropah. Penentangan ini merupakan cetusan kebangkitan masyarakat Islam sedunia terhadap penjajah Barat yang menakluki negara Islam. Penglibatan empayar Uthmaniyah dalam Perang Dunia Pertama di Eropah mempengaruhi kebangkitan Tok Janggut. Penentangan yang memperjuangkan agama ini kemudiannya dikaitkan dengan isu cukai yang dikenakan serta sikap membenci British. British berwaspada terhadap sokongan orang Melayu terhadap empayar Uthmaniyah yang terlibat dalam Perang Dunia Pertama kerana orang Melayu menganggap khalifah empayar Uthmaniyah sebagai pelindung umat Islam serta penaung bagi tanah suci Mekah dan Madinah. Kegagalan penentangan -

Remembering Operation Jaywick : Singapore's Asymmetric Warfare

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Remembering Operation Jaywick : Singapore’s Asymmetric Warfare Kwok, John; Li, Ian Huiyuan 2018 Kwok, J. & Li, I. H. (2018). Remembering Operation Jaywick : Singapore’s Asymmetric Warfare. (RSIS Commentaries, No. 185). RSIS Commentaries. Singapore: Nanyang Technological University. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/82280 Nanyang Technological University Downloaded on 24 Sep 2021 04:43:21 SGT Remembering Operation Jaywick: Singapore’s Asymmetric Warfare By John Kwok and Ian Li Synopsis Decades before the concept of asymmetric warfare became popular, Singapore was already the site of a deadly Allied commando attack on Japanese assets. There are lessons to be learned from this episode. Commentary 26 SEPTEMBER 2018 marks the 75th anniversary of Operation Jaywick, a daring Allied commando raid to destroy Japanese ships anchored in Singapore harbour during the Second World War. Though it was only a small military operation that came under the larger Allied war effort in the Pacific, it is worth noting that the methods employed bear many similarities to what is today known as asymmetric warfare. States and militaries often have to contend with asymmetric warfare either as part of a larger campaign or when defending against adversaries. Traditionally regarded as the strategy of the weak, it enables a weaker armed force to compensate for disparities in conventional force capabilities. Increasingly, it has been employed by non-state actors such as terrorist groups and insurgencies against the United States and its allies to great effect, as witnessed in Iraq, Afghanistan, and more recently Marawi. -

PDF for Download

THE AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL National Collection Development Plan The Australian War Memorial commemorates the sacrifice of Australian servicemen and servicewomen who have died in war. Its mission is to help Australians to remember, interpret and understand the Australian experience of war and its enduring impact on Australian society. The Memorial was conceived as a shrine, museum and archive that supports commemoration through understanding. Its development through the years has remained consistent with this concept. Today the Memorial is a commemorative centrepiece; a museum, housing world-class exhibitions and a diverse collection of material relating to the Australian experience of war; and an archive holding extensive official and unofficial documents, diaries and papers, making the Memorial a centre of research for Australian military history. The Australian War Records Section Trophy Store at Peronne. AWM E03684 The National Collection The Australian War Memorial houses one of Australia’s most significant museum collections. Consisting of historical material relating to Australian military history, the National Collection is one of the most important means by which the Memorial presents the stories of Australians who served in war. The National Collection is used to support exhibitions in the permanent galleries, temporary and travelling exhibitions, education and public programs, and the Memorial’s website. Today, over four million items record the details of Australia’s involvement in military conflicts from colonial times to the present day. Donating to the National Collection The National Collection is developed largely by donations received from serving or former members of Australia’s military forces and their families. These items come to the Memorial as direct donations or bequests, or as donations under the Cultural Gifts program. -

Catalogue 210 JULY 2018

1 Catalogue 210 JULY 2018 Mick at the ‘coal face’ 210/185. (6751) Jacobs, J.W. & Bridgland, R.J. Through: The Story of Signals, 8th Australian Division and Signals AIF Ma- laya. 8 Division Signal Associa- tion, Sydney, 1949. 1st ed, *a very good copy of a scarce book detailing the history of Signals units in Sin- gapore and Malaya before becoming POWs for the remainder of the war. Page 16 210/171. (10383) Bellett, A.C. (ed). Jolly Good Company: Memories of Service with "B" Com- pany, No. 2 (Fremantle) Battalion, Volunteer Defence Corps, during the Second World War, 1939-1945. 1st ed, **this is a very rare account of the Fremantle company of the VDC. Page 15 2 Glossary of Terms (and conditions) INDEX Returns: books may be returned for refund within 7 days and only if not as described in the catalogue. NOTE: If you prefer to receive this catalogue via email, let us know on in- [email protected] CATEGORY PAGE My Bookroom is open each day by appointment – preferably in the afternoons. Give me a call. Aviation 3 Abbreviations: 8vo =octavo size or from 140mm to 240mm, ie normal size book, 4to = quarto approx 200mm x 300mm (or coffee table size); d/w = dust wrapper; Espionage 4 pp = pages; vg cond = (which I thought was self explanatory) very good condition. Other dealers use a variety including ‘fine’ which I would rather leave to coins etc. Illus = illustrations (as opposed to ‘plates’); ex lib = had an earlier life in library Military Biography 5 service (generally public) and is showing signs of wear (these books are generally 1st editions mores the pity but in this catalogue most have been restored); eps + end papers, front and rear, ex libris or ‘book plate’; indicates it came from a Military General 6 private collection and has a book plate stuck in the front end papers. -

NEWSLETTER 21 FINAL.Pub

ServingServing FaithfullyFaithfully Newsletter of the Catholic Diocese of the Australian Defence Force August 2015 Published by the Diocesan Curia. Editor: Monsignor Peter O'Keefe AM VG EV Issue # 21 From the Vicar General Monsignor Peter O’Keefe AM VG EV To Love is to Serve art of our DNA as Members of the Defence Force Synod on the Family— The Year of Consecrated P is our preference to get on with the 'doing' rather Life coincides with the Synod on the Family to be than drowning in the endless use of words! held in Rome on 4‐25 October this year. In calling Since his Papal inauguration in 2013, Pope Francis has the Synod, Pope Francis asks that its underlying used gestures to speak more than words, a trait consistent spirit be one of listening to the needs of our with his namesake: Saint Francis of Assisi often instructed his families in today's world. It is vital to help, support young friars that actions are far more potent than words. He and encourage our families , especially those who was reported to have said ‘In everything we do, we must are experiencing difficulties in family life. The Pope preach the Gospel. But only when absolutely necessary should speaks about the ‘Gospel of the Family’.e In th messy, we use words.’ imperfect reality of family life, God is present. We are very The Church has always upheld the dignity of military mindful of our Defence families. May our families strive to be service when it serves the cause of right, in justice and for the places that speak of love in action. -

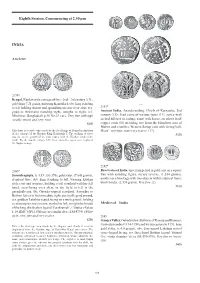

Eighth Session, Commencing at 2.30 Pm INDIA

Eighth Session, Commencing at 2.30 pm INDIA Ancient 2179* Bengal, Kushan style coinage of the c.2nd - 3rd century A.D., gold dinar 7.21 grams, imitating Kanishka I, obv, king standing part to left holding trident and sprinkling incense over altar, rev. 2181* goddess Ardoxsho standing right, tamgha to right, (cf. Ancient India, Ananda-ending, Chiefs of Karnataka, 2nd Mitchiner, Bangladesh p.30 No.23 var.). Very fine although century A.D., lead coins of various types (11), som,e with weakly struck and very rare. arched hill/tree in railing, some with horse, an others lead/ $450 copper coins (60 including two from the Mandisor area of Malwa and a uniface Western Satrap coin with facing bull. This dinar is a crude copy struck by the local kings of Bengal in imitation Good - very fine, some very scarce. (17) of the coinage of the Kushan King Kanbishka I. The striking of these $350 was due to the growth of the trade routes with the Kushan lands in the north. By the fourth century A.D. these imitative types were replaced by Gupta coinage. 2182* 2180* Bracteates of India, uncertain period in gold, one on a square Samudragupta, (c.A.D. 330-370), gold stater, (7.648 grams), flan with standing figure, incuse reverse, (1.284 grams), standard type, obv. king standing to left, wearing Kushan another as a brockage with two objects within eliptical frame style coat and trousers, holding a tall standard with his left block border, (2.536 grams). Very fine. (2) hand, sacrificing over altar, in the field to left is the $100 garudadhvaja, the Garuda-topped standard, Samudra in Brahmi letters to his immediate right, poetical legend around, rev. -

Detailed Species Accounts from The

Threatened Birds of Asia: The BirdLife International Red Data Book Editors N. J. COLLAR (Editor-in-chief), A. V. ANDREEV, S. CHAN, M. J. CROSBY, S. SUBRAMANYA and J. A. TOBIAS Maps by RUDYANTO and M. J. CROSBY Principal compilers and data contributors ■ BANGLADESH P. Thompson ■ BHUTAN R. Pradhan; C. Inskipp, T. Inskipp ■ CAMBODIA Sun Hean; C. M. Poole ■ CHINA ■ MAINLAND CHINA Zheng Guangmei; Ding Changqing, Gao Wei, Gao Yuren, Li Fulai, Liu Naifa, Ma Zhijun, the late Tan Yaokuang, Wang Qishan, Xu Weishu, Yang Lan, Yu Zhiwei, Zhang Zhengwang. ■ HONG KONG Hong Kong Bird Watching Society (BirdLife Affiliate); H. F. Cheung; F. N. Y. Lock, C. K. W. Ma, Y. T. Yu. ■ TAIWAN Wild Bird Federation of Taiwan (BirdLife Partner); L. Liu Severinghaus; Chang Chin-lung, Chiang Ming-liang, Fang Woei-horng, Ho Yi-hsian, Hwang Kwang-yin, Lin Wei-yuan, Lin Wen-horn, Lo Hung-ren, Sha Chian-chung, Yau Cheng-teh. ■ INDIA Bombay Natural History Society (BirdLife Partner Designate) and Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History; L. Vijayan and V. S. Vijayan; S. Balachandran, R. Bhargava, P. C. Bhattacharjee, S. Bhupathy, A. Chaudhury, P. Gole, S. A. Hussain, R. Kaul, U. Lachungpa, R. Naroji, S. Pandey, A. Pittie, V. Prakash, A. Rahmani, P. Saikia, R. Sankaran, P. Singh, R. Sugathan, Zafar-ul Islam ■ INDONESIA BirdLife International Indonesia Country Programme; Ria Saryanthi; D. Agista, S. van Balen, Y. Cahyadin, R. F. A. Grimmett, F. R. Lambert, M. Poulsen, Rudyanto, I. Setiawan, C. Trainor ■ JAPAN Wild Bird Society of Japan (BirdLife Partner); Y. Fujimaki; Y. Kanai, H. -

Semut: the Untold Story of a Secret Australian Operation in WWII Borneo

Semut: the untold story of a secret Australian operation in WWII Borneo by Christine Helliwell Penguin Random House: North Sydney, NSW; 2021; 562 pp; ISBN 9780143790020 (paperback); RRP $34.99 If war is innate to human societies, then anthro - explores the dynamics between the European, Malay pologist Christine Helliwell is well placed to provide and Chinese expatriates in Borneo, as well as the insights that are atypical of most military histories. Her occupying Japanese. Compared to earlier accounts, account of this small operation of the Second World her account provides a more balanced perspective on War is insightful and fascinating. the Semut operations – particularly the complex and Operation Semut was undertaken by Australia's nuanced relationships between the various groups. Services Reconnaissance Department in Sarawak in Helliwell’s narrative critically examines the mid-1945 as part of the Allied campaign to recapture numerous contradictions between previous accounts North Borneo. Its two main objectives were to gather of Operation Semut. She also delves deeply into the intelligence and to encourage the indigenous people local Dayak tradition of headhunting which the colonial to launch a guerrilla war against the Japanese. rulers had worked to eradicate, but which, conversely, The operation was commanded by Major ‘Toby’ was encouraged as part of the campaign. Carter and was divided into three main parties: Semut Semut includes a number of images as well as over 1, 2 and 3. This book is the first of two volumes and a dozen detailed and well-produced maps. This covers Semut 2 and 3, in which 60 Allied soldiers took account of Semut and its 78 pages of endnotes and part. -

The Allied Intelligence Bureau

APPENDIX 4 THE ALLIED INTELLIGENCE BUREAU Throughout the last three volumes of this series glimpses have bee n given of the Intelligence and guerilla operations of the various organisa- tions that were directed by the Allied Intelligence Bureau . The story of these groups is complex and their activities were diverse and so widesprea d that some of them are on only the margins of Australian military history . They involved British, Australian, American, Dutch and Asian personnel , and officers and men of at least ten individual services . At one time o r another A.I.B. controlled or coordinated eight separate organisations. The initial effort to establish a field Intelligence organisation in what eventually became the South-West Pacific Area was made by the Aus- tralian Navy which, when Japan attacked, had a network of coastwatche r stations throughout the New Guinea territories . These were manned by people living in the Australian islands and the British Sololnons . The development and the work of the coastwatchers is described in some detai l in the naval series of this history and in The Coast Watchers (1946) by Commander Feldt, who directed their operations. The expulsion of Allied forces from Malaya, the Indies and the Philip- pines, and also the necessity of establishing Intelligence agencies withi n the area that the enemy had conquered brought to Australia a numbe r of Allied Intelligence staffs and also many individuals with intimate know - ledge of parts of the territories the Japanese now occupied . At the summit were, initially, the Directors of Intelligence of the thre e Australian Services . -

Special Unit Force

HERITAGE SERVICES INFORMATION SHEET NUMBER 14 THE KRAIT AND “Z” SPECIAL UNIT FORCE Did you know that as a dress rehearsal for the Krait’s first attack on Singapore harbour during World War II, the Scorpion party raided shipping anchored in Townsville harbour? Commandos from “Z” Special Force Unit, attached mock up limpet mines to ships in the Cleveland Bay and the Australian War Memorial Negative Number harbour and demonstrated the city’s PO1806.008. Photograph showing lack of maritime security during members of “Z” Force training in canoes on the Hawkesbury River. wartime. The Scorpion Raid Sam Carey was given information that the At 11 pm on 19 June 1943 the train from Black River was tidal and that his party Cairns stopped just before the Black River would have no difficulty paddling down it to bridge. 10 soldiers laden with gear the sea. He was shocked when he jumped from the last carriage of the train. discovered that the river was a series of Their mission was to launch a mock raid waterholes separated by stretches of on ships in Townsville harbour to test their sand. This meant the men had to carry ability to undertake a similar mission and drag the boats between the aimed at Japanese shipping. Naval waterholes. It was not until late on the 20 authorities in Townsville were unaware June that they reached the mouth of the that the raid would take place as the group Black River and the shores of Halifax Bay. needed to obtain a true indicator of their The men were tired and exhausted by this preparedness. -

Revision of the Hydaticus (Prodaticus)

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Koleopterologische Rundschau Jahr/Year: 2015 Band/Volume: 85_2015 Autor(en)/Author(s): Wewalka Günther Artikel/Article: Revision of the Hydaticus (Prodaticus) sexguttatus species group, and resembling species from the Palearctic, Oriental, Australian and Pacific Regions (Coleoptera: Dytiscidae) 7-55 ©Wiener Coleopterologenverein (WCV), download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Koleopterologische Rundschau 85 7–55 Wien, September 2015 Revision of the Hydaticus (Prodaticus) sexguttatus species group, and resembling species from the Palearctic, Oriental, Australian and Pacific Regions (Coleoptera: Dytiscidae) G. WEWALKA Abstract The Palearctic, Oriental, Australian and Pacific species of the Hydaticus (Prodaticus) sexguttatus species group (Coleoptera, Dytiscidae) are revised. Fourteen species including five new ones (H. balkei sp.n., H. hajeki sp.n., H. hendrichi sp.n., H. marlenae sp.n. and H. stastnyi sp.n.) are des- cribed. Five species of the H. fabricii group including one new species and one new subspecies (H. agaboides SHARP, 1882, H. ephippiiger RÉGIMBART, 1899, H. larsoni sp.n., H. pulcher CLARK, 1863, H. sellatus sabahensis ssp.n. and H. sellatus sellatus RÉGIMBART, 1883) are also treated herein, because their elytral marks or their male genitalia are similar to those of some species of the H. sexguttatus group. Lectotypes are designated for H. bengalensis RÉGIMBART, 1899, H. ephippiiger RÉGIMBART, 1899, H. fractifer WALKER, 1858, H. laetabilis RÉGIMBART, 1899, H. macularis RÉGIMBART, 1899, H. nigritulus RÉGIMBART, 1899, H. reductus RÉGIMBART, 1899, H. rhantaticoides RÉGIMBART, 1892, H. schultzei ZIMMERMANN, 1924, H. sellatus RÉGIMBART, 1883, and H. sexguttatus RÉGIMBART, 1899. New synonymies: H. -

A Revision of Tetrastigma (Miq.) Planch. (Vitaceae) in Sarawak, Borneo

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317746026 A revision of Tetrastigma (Miq.) Planch. (Vitaceae) in Sarawak, Borneo Article in Malayan Nature Journal · January 2017 CITATION READS 1 324 4 authors, including: Wan Nuur Fatiha Wan Zakaria Aida Shafreena Ahmad Puad University Malaysia Sarawak University Malaysia Sarawak 5 PUBLICATIONS 10 CITATIONS 9 PUBLICATIONS 30 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Ramlah bt Zainudin University Malaysia Sarawak 59 PUBLICATIONS 205 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Characterizations of peptides from Borneon frogs skin secretion View project Molecular Phlogeny of Genus Hylarana View project All content following this page was uploaded by Wan Nuur Fatiha Wan Zakaria on 02 May 2018. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Malayan Nature Journal 2017, 69(1), 71 - 90 (Updated 31-5-2017) A revision of Tetrastigma (Miq.) Planch. (Vitaceae) in Sarawak, Borneo WAN NUUR FATIHA WAN ZAKARIA1, AIDA SHAFREENA AHMAD PUAD1, *, RAMLAH ZAINUDIN2 and A. LATIFF3 Abstract: A revision of the genus Tetrastigma (Miq.) Planch. in Sarawak is presented. A total of 11 Tetrastigma species in Sarawak are recorded namely T. brunneum Merrill, T. dichotomum (Blume) Planch., T. diepenhorstii (Miq.) Latiff, T. dubium (Laws.) Planch., T. glabratum (Blume) Planch., T. hookeri (Lawson) Planch., T. megacarpum Latiff, T. papillosum (Blume) Planch., T. pedunculare (Wall. ex Laws.) Planch., T. rafflesiae (Miq.) Planch., and T. tetragynum Planch. Morphological descriptions are given for each taxon, as well as a key for identification. A general discussion on the growth habits and morphology of stem, inflorescence, flowers, fruits and seeds is also given.