Governance and Natural Resources Management: Emerging Lessons from ICRAF-SANREM Collaboration in the Philippines1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Energy Projects in Region X

Energy Projects in Region X Lisa S. Go Chief, Investment Promotion Office Department of Energy Energy Investment Briefing – Region X 16 August 2018 Cagayan De Oro City, Misamis Oriental Department of Energy Empowering the Filipino Energy Projects in Northern Mindanao Provinces Capital Camiguin Mambajao Camiguin Bukidnon Malaybalay Misamis Oriental Cagayan de Oro Misamis Misamis Misamis Occidental Oroquieta Occidental Gingoog Oriental City Lanao del Norte Tubod Oroquieta CIty Cagayan Cities De Oro Cagayan de Oro Highly Urbanized (Independent City) Iligan Ozamis CIty Malaybalay City Iligan Highly Urbanized (Independent City) Tangub CIty Malayabalay 1st Class City Bukidnon Tubod 1st Class City Valencia City Gingoog 2nd Class City Valencia 2nd Class City Lanao del Ozamis 3rd Class City Norte Oroquieta 4th Class City Tangub 4th Class City El Salvador 6th Class City Source: 2015 Census Department of Energy Empowering the Filipino Energy Projects in Region X Summary of Energy Projects Per Province Misamis Bukidnon Camiguin Lanao del Norte Misamis Oriental Total Occidental Province Cap. Cap. Cap. Cap. No. No. No. No. Cap. (MW) No. No. Cap. (MW) (MW) (MW) (MW) (MW) Coal 1 600 4 912 1 300 6 1,812.0 Hydro 28 338.14 12 1061.71 8 38.75 4 20.2 52 1,458.8 Solar 4 74.49 1 0.025 13 270.74 18 345.255 Geothermal 1 20 1 20.0 Biomass 5 77.8 5 77.8 Bunker / Diesel 4 28.7 1 4.1 2 129 6 113.03 1 15.6 14 290.43 Total 41 519.13 1 4.10 16 1,790.74 32 1,354.52 6 335.80 96 4,004.29 Next Department of Energy Empowering the Filipino As of December 31, 2017 Energy Projects in Region X Bukidnon 519.13 MW Capacity Project Name Company Name Location Resource (MW) Status 0.50 Rio Verde Inline (Phase I) Rio Verde Water Constortium, Inc. -

Microfinance and Financial Institutions in Bukidnon

Microfinance and Financial Institutions in Bukidnon Author: Beethoven Morales Research Institute for Mindanao Culture (RIMCU) BASIS CRSP This posting is provided by the BASIS CRSP Management Entity Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, University of Wisconsin-Madison Tel: (608) 262-5538 Email: basis [email protected] http://www.basis.wisc.edu October 2004 Beethoven Morales Research Institute for Mindanao Culture [email protected] BASIS CRSP outputs posted on this website have been formatted to conform with other postings but the contents have not been edited. This output was made possible in part through support provided by the US Agency for International Development (USAID), under the terms of Grant No. LAG-A-00-96-90016-00, and by funding support from the BASIS Collaborative Research Support Program and its management entity, the Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA. All views, interpretations, recommendations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the supporting or cooperating organizations. Copyright © by author. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this document for noncommercial purposes by any means, provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies. ii Microfinance and Financial Institutions in Bukidnon Beethoven C. Morales Research Institute for Mindanao Culture, Xavier University Cagayan de Oro City, Philippines August 2004 1. I NTRODUCTION This report looks at the relationship between microfinance and financial institutions in Bukidnon within the context of the national and local (province) poverty conditions in the Philippines. The report examines government involvement in the provision of credit to low-income groups, and the importance and contributions of nongovernment microfinance providers. -

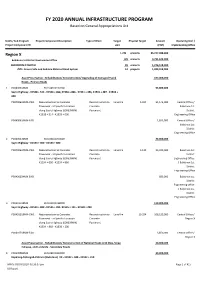

FY 2020 ANNUAL INFRASTRUCTURE PROGRAM Based on General Appropriations Act

FY 2020 ANNUAL INFRASTRUCTURE PROGRAM Based on General Appropriations Act UACS / Sub Program Project Component Description Type of Work Target Physical Target Amount Operating Unit / Project Component ID Unit (PHP) Implementing Office Region X 1,228 projects 36,227,088,000 Bukidnon 1st District Engineering Office 139 projects 4,791,103,000 BUKIDNON (FOURTH) 28 projects 1,274,518,000 OO1: Ensure Safe and Reliable National Road System 14 projects 1,029,018,000 Asset Preservation - Rehabilitation/ Reconstruction/ Upgrading of Damaged Paved 197,000,000 Roads - Primary Roads 1. P00400633MN 310104100197000 53,000,000 Sayre Highway - K1528 + 514 - K1529 + 000, K1530 + 896 - K1531 + 456, K1531 + 487 - K1533 + 000 P00400633MN-CW1 Reconstruction to Concrete Reconstruction to Lane Km 5.014 51,145,000 Central Office / Pavement - at Specific Locations Concrete Bukidnon 1st along Sayre Highway (S00639MN) Pavement District K1528 + 514 - K1533 + 000 Engineering Office P00400633MN-EAO 1,855,000 Central Office / Bukidnon 1st District Engineering Office 2. P00400634MN 310104100254000 34,000,000 Sayre Highway - K1534 + 000 - K1534 + 860 P00400634MN-CW1 Reconstruction to Concrete Reconstruction to Lane Km 3.132 33,320,000 Bukidnon 1st Pavement - at Specific Locations Concrete District along Sayre Highway (S00639MN) Pavement Engineering Office K1534 + 000 - K1534 + 860 / Bukidnon 1st District Engineering Office P00400634MN-EAO 680,000 Bukidnon 1st District Engineering Office / Bukidnon 1st District Engineering Office 3. P00401518MN 310104100198000 110,000,000 Sayre Highway - K1534 + 860 - K1535 + 091, K1535 + 121 - K1538 + 200 P00401518MN-CW1 Reconstruction to Concrete Reconstruction to Lane Km 10.294 106,150,000 Central Office / Pavement - at Specific Locations Concrete Region X along Sayre Highway (S00639MN) Pavement K1534 + 860 - K1538 + 200 P00401518MN-EAO 3,850,000 Central Office / Region X Asset Preservation - Rehabilitation/ Reconstruction of National Roads with Slips, Slope 20,000,000 Collapse, and Landslide - Secondary Roads 4. -

Lay out Pdf.Pmd

Developing the Local Natural Resource Management Plan A Guide to Facilitators Delia C Catacutan Eduardo E Queblatin Caroline E Duque Lyndon J Arbes To more fully reflect our global reach, as well as our more balanced research and development agenda, we adopted a new brand name in 2002 ‘World Agroforestry Centre’. Our legal name - International Centre for Research in Agroforestry - remains unchanged, and so our acronym as a Future Harvest Centre remains the same. Views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the World Agroforestry Centre. All images remain the sole property of their source and may not be used for any purpose without written permission of the source. About this manual: Developing the Local Natural Resource Management Plan is a guide for facilitators and development workers, from both government and non-government organizations. The content of this guidebook outlines ICRAF’s experiences in working with different local governments in Mindanao in formulating and implementing NRM programs. Citation: Catacutan D, Queblatin E, Duque C, Arbes L. 2006. Developing the Local Natural Resource Management Plan: A Guide to Facilitators. Bukidnon, Philippines: World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF). ISBN: 978-971-93135-3-9 Copyright 2006 by the World Agroforestry Centre ICRAF - Philippines 2/F College of Forestry and Natural Resources Administration Building PO Box 35024, UPLB, College, Laguna 4031, Philippines Tel.: +63 49 536 2925; +63 49 536 7645 Fax: +63 49 536 4521 Email: [email protected] -

Province of Bukidnon

Department of Environment and Natural Resources MINES & GEOSCIENCES BUREAU Regional Office No. X Macabalan, Cagayan de Oro City DIRECTORY OF PRODUCING MINES AND QUARRIES IN REGION 10 CALENDAR YEAR 2017 PROVINCE OF BUKIDNON Head Office Mine Site Mine Site Municipality/ Head Office Mailing Head Office Fax Head Office E- Head Office Mine Site Mailing Mine Site Type of Date Date of Area Municipality, Year Region Mineral Province Commodity Contractor Operator Managing Official Position Telephone Telephone Email Permit Number Barangay Status TIN City Address No. mail Address Website Address Fax Permit Approved Expirtion (has.) Province No. No. Address Commercial Sand and Gravel San Isidro, Valencia San Isidro, Valencia CSAG-2001-17- Valencia City, Non-Metallic Bukidnon Valencia City Sand and Gravel Abejuela, Jude Abejuela, Jude Permit Holder City 0926-809-1228 City 24 Bukidnon Operational 2017 10 CSAG 12-Jul-17 12-Jul-18 1 ha. San Isidro Manolo Manolo JVAC & Damilag, Manolo fedemata@ya Sabangan, Dalirig, CSAG-2015-17- Fortich, 931-311- 2017 10 Non-Metallic Bukidnon Fortich Sand and Gravel VENRAY Abella, Fe D. Abella, Fe D. Permit Holder Fortich, Bukidnon 0905-172-8446 hoo.com Manolo Fortich CSAG 40 02-Aug-17 02-Aug-18 1 ha. Dalirig Bukidnon Operational 431 Nabag-o, Valencia agbayanioscar Nabag-o, Valencia Valencia City, 495-913- 2017 10 Non-Metallic Bukidnon Valencia City Sand and Gravel Agbayani, Oscar B. Agbayani, Oscar B. Permit Holder City 0926-177-3832 [email protected] City CSAG CSAG-2017-09 08-Aug-17 08-Aug-18 2 has. Nabag-o Bukidnon Operational 536 Old Nongnongan, Don Old Nongnongan, Don CSAG-2006- Don Carlos, 2017 10 Non-Metallic Bukidnon Don Carlos Sand and Gravel UBI Davao City Alagao, Consolacion Alagao, Consolacion Permit Holder Calrlos Carlos CSAG 1750 11-Oct-17 11-Oct-18 1 ha. -

Crop Production of Northern Mindanao, Philippines: Its Contribution to the Regional Economy and Food Security

TROPICULTURA, 2015, 33,2,7790 Crop production of Northern Mindanao, Philippines: Its contribution to the Regional Economy and Food Security G.M. Dejarme–Calalang1*, L. Bock2 & G. Colinet2 Keywords: Northern Mindanao Crop production Economic contribution, Food security, Crop export Philippines Summary Résumé This paper presents the contribution of primary Production végétale à Mindanao nord, agricultural crops produced in Northern Mindanao to Philippines: contribution à l’économie its economy and food security of people with the régionale et à la sécurité alimentaire situational analysis and insights of the authors. Rice Cet article présente l’état de la situation et as the staple food of most Filipinos is insufficient in l’éclairage des auteurs quant à la contribution des quantity produced. Corn production is more than principales plantes cultivées à l’économie et à la enough for the total regional demand. White corn is sécurité alimentaire de la population dans la région preferred as secondary staple food, however the nord de Mindanao. Le riz qui constitue l’aliment corn industry emphasizes yellow corn production principal de la plupart des Philippins n’est pas and the bulk of this goes to raw materials for produit en quantité suffisante. La production de livestock and poultry feeds. Coconut, sugar, maïs est excédentaire par rapport à la demande pineapple and bananas significantly contribute to régionale. Le maïs blanc est préféré comme second agricultural exports. Coconut is processed before aliment principal, bien que l’industrie encourage la exporting which can offer employment in the rural production de maïs jaune; la majeure partie de ce areas. Sugarcane, pineapple and bananas have dernier servant à l’alimentation du bétail et de la created a change in the land use and hence volaille. -

General Description of the Manupali Watershed, Bukidnon

Mainstreaming Climate Change Adaptation in Watershed Management and Upland Farming in the Philippines Draft Final Report Florencia B. Pulhin 1, Rodel D. Lasco2, Ma. Victoria O. Espaldon3 and Dixon T. Gevana4 1 Forestry Development Center, College of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of the Philippines Los Banos 2 World Agroforestry Centre, 2nd Floor Khush Hall, IRRI 3School of Environmental Science and Management, University of the Philippines Los Banos 4 Environmental Forestry Programme, College of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of the Philippines Los Banos I. Introduction Being an archipelagic developing country composed of more than 7000 small islands, the Philippines is highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate related events such as tropical cyclones and ENSO. The Philippines is always battered by typhoons because it is geographically located in a typhoon belt area. Based on the 59 year period (1948- 2006), annual average number of typhoons occurring within the Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR) is around 19 to 20 (PAGASA, 2007). During the last two decades, an increasing trend on the number of strong typhoons (> 185 kph wind speed) hitting the Philippines has been observed. From 1990-1998, a total of seven strong typhoons have crossed the country (NDCC, 2000 and Typhoon 2000.com). Damages from these typhoons are staggering. They not only caused damage to properties but also claimed the lives of people. For instance, typhoon “Uring” (Thelma) which made a landfall in November 1991 caused the death of around 5101-8000 people and damaged properties amounting to PhP 1.045 billion. Typhoons ‘Ruping” (Mike) and “Rosing” (Angela) caused damage to properties of almost PhP 11B each. -

DSWD DROMIC Report #1 on the Mw 5.9 Earthquake Incident in Kadingilan, Bukidnon As of 20 November 2019, 6PM

DSWD DROMIC Report #1 on the Mw 5.9 Earthquake Incident in Kadingilan, Bukidnon as of 20 November 2019, 6PM Situation Overview On 18 November 2019 at 09:22 PM, a 5.9 moment magnitude (Mw) earthquake jolted the municipality of Kadingilan, Bukidnon (07.66°N, 124.89°E - 008 km N 24°W) with a tectonic origin and a depth of focus of 5 km. The earthquake was also felt in the neighboring municipalities of Bukidnon. Date/Time: 18 Nov 2019 - 09:22:08 PM Reported Intensities: Intensity VI - Kadingilan, Kalilangan, Don Carlos, Maramag, Kitaotao and San Fernando, Bukidnon Intensity V - Damulog, Talakag and Valencia City, Bukidnon; Midsayap, Cotabato; Kidapawan City; Marawi City Intensity IV - Impasugong and Malaybalay, Bukidnon; Malungon, Sarangani; Antipas, Cotabato, Rosario, Agusan Del Sur; Cotabato City; Davao City; Koronadal City; Cagayan De Oro City Intensity III - Malitbog, Bukidnon; Tupi, South Cotabato; Manticao, Misamis Oriental; Tubod and Bacolod, Lanao Del Norte; Alabel, Sarangani; Gingoog City; Pagadian City; Iligan City Intensity II - Polomolok, Lake Sebu and Tampakan, South Cotabato; Kiamba, Sarangani; Mambajao, Camiguin; Sindangan and Polanco, Zamboanga Del Norte; Molave, Zamboanga Del Sur; Dipolog City; General Santos City Intensity I - Zamboanga City Instrumental Intensities: Intensity IV - Cagayan De Oro City; Kidapawan City; Koronadal City; Malungon, Sarangani Intensity III - Gingoog City; Davao City; Tupi, South Cotabato; Alabel, Sarangani Intensity II - Kiamba, Sarangani; General Santos City Intensity I - Zamboanga City; Bislig City Expecting Damage: YES Expecting Aftershocks: YES Source: DOST-PHIVOLCS Earthquake Bulletin Page 1 of 3| DSWD DROMIC Report #1 on the Mw 5.9 Earthquake Incident in Kadingilan, Bukidnon as of 20 November 2019, 6PM I. -

Indigenous Peoples Plan PHI: Integrated Natural Resources And

Indigenous Peoples Plan Project Number: 41220-013 July 2019 PHI: Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project Community Management Plan for Bukidnon Tribe of San Luis, Malitboog, Bukidnon Prepared by Bukidnon community of Malitbog, Bukidnon for the Department of Environment and Natural Resources and Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 31 July 2019) Currency unit = philippine peso ₱ 1.00 = $ 0.0197 $ 1.00 = ₱ 50.8200 ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank ADSDPP - Ancestral Domain Sustainable Development and Protection Plan AFP - Armed Forces of the Philippines CADT - Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title CLUP - Community Land Use Plan CMP - community management plan COE - council of elders DENR - Department of Environment and Natural Resources DepEd - Department of Education DOH - Department of Health DTI - Department of Trade and Industry FPIC - free, prior and informed consent GO - government organizations ICC - indigenous cultural communities IGP - income generating project INREMP - Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project IP - indigenous peoples IPDF - indigenous people’s development framework IPMR - indigenous people mandatory representative IPO - indigenous people’s organization IPP - indigenous peoples plan IPRA - indigenous peoples rights act LGU - local government unit M&E - monitoring and evaluation Masl - meters above sea level MLGU - municipal local government unit MOA - memorandum of agreement NAMRIA - National Mapping and Resource Information Authority NCIP - National Commission on Indigenous People NGO - non-government organizations NGP - National Greening Program PNP - Philippine National Police PPMO - provincial project management officer RA - republic act RPCO - regional project coordination office SMA - Sabangaan Madasigon Association, Inc. SEC - Securities and Exchange Commission SPS - Safeguards Policy Statement TAKASAMA- Tagmaray, Kalipay, San Luis, Mabuhay Tribal Association, Inc. -

Province of Bukidnon

Department of Environment and Natural Resources MINES & GEOSCIENCES BUREAU Regional Office No. X Macabalan, Cagayan de Oro City DIRECTORY OF PRODUCING MINES AND QUARRIES IN REGION 10 CALENDAR YEAR 2018 PROVINCE OF BUKIDNON Mine Head Head Office Head Mine Site Mine Site Municipality/ Head Office Mailing Head Office Office E- Mine Site Mailing Type of Date Date of Area Municipality, Year Region Mineral Province Commodity Contractor Operator Managing Official Position Telephone Office Telepho Site Email Permit Number Barangay Status TIN City Address Fax No. mail Address Permit Approved Expirtion (has.) Province No. Website ne No. Fax Addres Address s Geredah Aggregates Inc., P-1, Brgy. Nicdao, 0917-705- Nicdao, Baungon, Baungon, 193-013- 2018 10 Non-Metallic Bukidnon Baungon Sand and Gravel Dahino, Gerardo E. Permit Holder None None None None None None CSAG CSAG-2017-18-3110/16/2018 10/16/2019 4.88 Nicdao Operational Rep. by Dahino, Baungon, Bukidnon 6914 Bukidnon Bukidnon 687 Gerardo E. P-9, Brgy. Castillanes, 0917-310- charlie_bebot@ Paradise, Cabanglasan, 265-857- 2018 10 Non-Metallic Bukidnon Cabanglasan Sand and Gravel UBI Castillanes, Charlie C. Permit Holder Cabulohan, None None None None None CSAG CSAG-2017-18-4111/14/2018 11/14/2019 3.00 Paradise Operational Charlie C. 4405 yahoo.com Cabanglasan Bukidnon 684 Cabanglasan P-9, Brgy. Anlugan, Castillanes, 0917-310- charlie_bebot@ Cabanglasan, 489-778- 2018 10 Non-Metallic Bukidnon Cabanglasan Sand and Gravel UBI Castillanes, Daisy M. Permit Holder Cabulohan, None None Cabanglasan, None None None CSAG CSAG-2018-02 1/24/2018 1/24/2019 3.00 Anlugan Operational Daisy M. -

Is the 13Th Largest River System In

Integrated River Basin Management and Development Master Plan for the Tagoloan River Basin ACRONYMS ADB Asian Development Bank AFF Agriculture, forestry, and fisheries AUSAid Australian Aid BFAR Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources BMB Biodiversity Management Bureau BWPDC Bukidnon Watershed Protection and Development Council CARAGA Region 13 CCA Climate Change Adaptation CCC Climate Change Commission CFNR College of Forestry and Natural Resources CFV Conservation Farming Villages CIA Cultural Impact Assessment CIDA Canadian International Development Agency CIS Community Irrigation System CLUP Comprehensive Land Use Plan CMU Central Mindanao University CSO Civil Society Organization CSR Corporate social responsibility DA Department of Agriculture DA-BSWM DA – Bureau of Soils and Water Management DA-NIA DA – National Irrigation Administration DEM Digital Elevation Models DENR Department of Environment and Natural Resources DFID Department for International Development DILG Department of Interior and Local Government DOH Department of Health DOST Department of Science and Technology DOST-ASTI DOST – Advanced Science and Technology Institute DOT Department of Tourism DOE Department of Energy DPSIR Driving Forces, Pressures, Impacts, State, and Response DPWH Department of Public Works and Highways DPWH-BRS DPWH – Bureau of Research and Standards DREAM Disaster Risk and Exposure Assessment for Mitigation DRR Disaster Risk Reduction DRRM Disaster Risk Reduction and Management DTI Department of Trade and Industry DWATS Decentralized Wastewater -

Manolo Fortich Water District

Initial Environmental Examination May 2020 Philippines: Water District Development Sector Project – Manolo Fortich Water District Prepared by Manolo Fortich Water District for the Local Water Utilities Administration and the Asian Development Bank. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Initial Environmental Examination May 2020 Philippines: Water District Development Sector Project MANOLO FORTICH WATER DISTRICT Prepared by Manolo Fortich Water District for the Local Water Utilities Administration and the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 20 March 2020) Currency unit – peso (Php) Php1.00 = $0.01955 $1.00 = Php 51.15 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank AO – Administrative Order APs – Affected Persons AQI – Air Quality Index AWWA – American Water Works Association BMB – Biodiversity Management Bureau CBMF – Community Based Management Forest CCC – Climate Change Commission CDO – Cease and Desist Order CEMP – Contractor’s Environmental Management Plan CNC – Certificate of Non- Coverage DAO – Department Administrative Order DDR – Due Diligence Report