Replicating Models of Institutional Innovation for Devolved, Participatory Watershed Management1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inspection Bukidnon

INSPECTION BUKIDNON Name of Establishment Address No. of Type of Industry Type of Condition Workers 1 AGLAYAN PETRON SERVICE CENTER POB. AGLAYAN, MALAYBALAY CITY 15 RETAIL HAZARDOUS 2 AGT MALAYBALAY PETRON (BRANCH) SAN VICENTE ST., MALAYBALAY CITY 10 RETAIL HAZARDOUS 3 AGT PETRON SERVICE CENTER SAN JOSE, MALAYBALAY CITY 15 RETAIL HAZARDOUS 4 AIDYL STORE POB. MALAYBALAY CITY 13 RETAIL HAZARDOUS 5 ALAMID MANPOWER SERVICES POB. AGLAYAN, MALAYBALAY CITY 99 NON-AGRI NON-HAZARDOUS 6 ANTONIO CHING FARM STA. CRUZ, MALAYBALAY CITY 53 AGRI HAZARDOUS 7 ASIAN HILLS BANK, INC. FORTICH ST., MALAYBALAY CITY 21 AGRI NON-HAZARDOUS 8 BAKERS DREAM (G. TABIOS BRANCH) T. TABIOS ST., MALAYBALAY CITY 10 RETAIL NON-HAZARDOUS 9 BAO SHENG ENTERPRISES MELENDES ST., MALAYBALAY CITY 10 RETAIL NON-HAZARDOUS 10 BELLY FARM KALASUNGAY, MALAYBALAY CITY 13 AGRI HAZARDOUS 11 BETHEL BAPTIST CHURCH SCHOOL FORTICH ST., MALAYBALAY CITY 19 PRIV. SCH NON-HAZARDOUS 12 BETHEL BAPTIST HOSPITAL SAYRE HIWAY, MALAYBALAY CITY 81 HOSPITAL NON-HAZARDOUS NON-HAZARDOUS 13 BUGEMCO LEARNING CENTER SAN VICTORES ST., MALAYBALAY CITY 10 PRIV. SCH GUILLERMO FORTICH ST., 14 BUKIDNON PHARMACY COOPERATIVE MALAYBALAY CITY 11 RETAIL NON-HAZARDOUS 15 CAFE CASANOVA (BRANCH) MAGSAYSAY ST., MALAYBALAY CITY 10 SERVICE NON-HAZARDOUS 16 CASCOM COMMERCIAL POB. AGLAYAN, MALAYBALAY CITY 30 RETAIL NON-HAZARDOUS CASISNG CHRISTIAN SCHOOL OF M NON-HAZARDOUS 17 MALAYBALAY CASISANG, MALAYBALAY CITY 34 PRIV. SCH A 18 CEBUANA LHUILLIER PAWNSHOP FORTICH ST., MALAYBALAY CITY 10 FINANCING NON-HAZARDOUS L 19 CELLUCOM DEVICES -

NO. TENEMENT ID TENEMENT HOLDER DATE DATE AREA (Has

Annex "B" MINING TENEMENT STATISTICS REPORT AS OF MARCH 2019 MGB REGIONAL OFFICE NO. X MINERAL PRODUCTION SHARING AGREEMENT (MPSA) I. Approved and Registered NO. TENEMENT ID TENEMENT HOLDER DATE DATE LOCATION AREA (has.) COMMODITY PREVIOUS STATUS/REMARKS FILED APPROVED Barangay Mun./'City Province HOLDER 1 MPSA - 039-96-X Holcim Resources and Development 8/3/1993 4/1/1996 Poblacion Lugait Misamis Oriental 129.6974 Shale Alsons Cement * On final rehabilitation. Corporation Corporation * Assigned to HRDC effective January 18, 2016. * Order of Approval registered on June 07, 2016. 2 MPSA - 031-95-XII Mindanao Portland Cement Corp. 4/29/1991 12/26/1995 Kiwalan Iligan City Lanao del Norte 323.0953 Limestone/Shale None * Corporate name changed to Republic Cement Iligan, Inc. (changed management to Lafarge Kalubihan * Officially recognized by MGB-X in its letter of March 9, 2016. Mindanao, Inc. and to Republic Cement Taguibo Mindanao, Inc.) 3 MPSA - 047-96-XII Holcim Resources and Development 8/21/1995 7/18/1996 Talacogon Iligan City Lanao del Norte 397.68 Limestone/Shale Alsons Cement * Assigned to HRDC effective January 18, 2016. Corporation Dalipuga Corporation * Order of Approval registered on June 07, 2016. - Lugait Misamis Oriental 4 MPSA-104-98-XII Iligan Cement Corporation 9/10/1991 2/23/1998 Sta Felomina Iligan City Lanao del Norte 519.09 Limestone/Shale None * Corporate name changed to Republic Cement Iligan, Inc. (changed management to Lafarge Bunawan * Officially recognized by MGB-X in its letter of March 9, 2016. Iligan, Inc. and to Republic Cement Kiwalan Iligan, Inc.) 5 MPSA - 105-98-XII MCCI Corporation 6/18/1991 2/23/1998 Kiwalan Iligan City Lanao del Norte and 26.7867 Limestone Maria Cristina * Existing but operation is suspended. -

Energy Projects in Region X

Energy Projects in Region X Lisa S. Go Chief, Investment Promotion Office Department of Energy Energy Investment Briefing – Region X 16 August 2018 Cagayan De Oro City, Misamis Oriental Department of Energy Empowering the Filipino Energy Projects in Northern Mindanao Provinces Capital Camiguin Mambajao Camiguin Bukidnon Malaybalay Misamis Oriental Cagayan de Oro Misamis Misamis Misamis Occidental Oroquieta Occidental Gingoog Oriental City Lanao del Norte Tubod Oroquieta CIty Cagayan Cities De Oro Cagayan de Oro Highly Urbanized (Independent City) Iligan Ozamis CIty Malaybalay City Iligan Highly Urbanized (Independent City) Tangub CIty Malayabalay 1st Class City Bukidnon Tubod 1st Class City Valencia City Gingoog 2nd Class City Valencia 2nd Class City Lanao del Ozamis 3rd Class City Norte Oroquieta 4th Class City Tangub 4th Class City El Salvador 6th Class City Source: 2015 Census Department of Energy Empowering the Filipino Energy Projects in Region X Summary of Energy Projects Per Province Misamis Bukidnon Camiguin Lanao del Norte Misamis Oriental Total Occidental Province Cap. Cap. Cap. Cap. No. No. No. No. Cap. (MW) No. No. Cap. (MW) (MW) (MW) (MW) (MW) Coal 1 600 4 912 1 300 6 1,812.0 Hydro 28 338.14 12 1061.71 8 38.75 4 20.2 52 1,458.8 Solar 4 74.49 1 0.025 13 270.74 18 345.255 Geothermal 1 20 1 20.0 Biomass 5 77.8 5 77.8 Bunker / Diesel 4 28.7 1 4.1 2 129 6 113.03 1 15.6 14 290.43 Total 41 519.13 1 4.10 16 1,790.74 32 1,354.52 6 335.80 96 4,004.29 Next Department of Energy Empowering the Filipino As of December 31, 2017 Energy Projects in Region X Bukidnon 519.13 MW Capacity Project Name Company Name Location Resource (MW) Status 0.50 Rio Verde Inline (Phase I) Rio Verde Water Constortium, Inc. -

Download Document (PDF | 853.07

3. DAMAGED HOUSES (TAB C) • A total of 51,448 houses were damaged (Totally – 14,661 /Partially – 36,787 ) 4. COST OF DAMAGES (TAB D) • The estimated cost of damages to infrastructure, agriculture and school buildings amounted to PhP1,399,602,882.40 Infrastructure - PhP 1,111,050,424.40 Agriculture - PhP 288,552,458.00 II. EMERGENCY RESPONSE MANAGEMENT A. COORDINATION MEETINGS • NDRRMC convened on 17 December 2011which was presided over by the SND and Chairperson, NDRRMC and attended by representatives of all member agencies. His Excellency President Benigno Simeon C. Aquino III provided the following guidance to NDRRMC Member Agencies : ° to consider long-term mitigation measures to address siltation of rivers, mining and deforestation; ° to identify high risk areas for human settlements and development and families be relocated into safe habitation; ° to transfer military assets before the 3-day warning whenever a typhoon will affect communities at risks; ° to review disaster management protocols to include maintenance and transportation costs of these assets (air, land, and maritime); and ° need to come up with a Crisis Manual for natural disasters ° The President of the Republic of the Philippines visited RDRRMC X on Dec 21, 2011 to actually see the situation in the area and condition of the victims particularly in Cagayan de Oro and Iligan City and issued Proclamation No. 303 dated December 20, 2011, declaring a State of National Calamity in Regions VII, IX, X, XI, and CARAGA • NDRRMC formally accepted the offer of assistance from -

Microfinance and Financial Institutions in Bukidnon

Microfinance and Financial Institutions in Bukidnon Author: Beethoven Morales Research Institute for Mindanao Culture (RIMCU) BASIS CRSP This posting is provided by the BASIS CRSP Management Entity Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, University of Wisconsin-Madison Tel: (608) 262-5538 Email: basis [email protected] http://www.basis.wisc.edu October 2004 Beethoven Morales Research Institute for Mindanao Culture [email protected] BASIS CRSP outputs posted on this website have been formatted to conform with other postings but the contents have not been edited. This output was made possible in part through support provided by the US Agency for International Development (USAID), under the terms of Grant No. LAG-A-00-96-90016-00, and by funding support from the BASIS Collaborative Research Support Program and its management entity, the Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA. All views, interpretations, recommendations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the supporting or cooperating organizations. Copyright © by author. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this document for noncommercial purposes by any means, provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies. ii Microfinance and Financial Institutions in Bukidnon Beethoven C. Morales Research Institute for Mindanao Culture, Xavier University Cagayan de Oro City, Philippines August 2004 1. I NTRODUCTION This report looks at the relationship between microfinance and financial institutions in Bukidnon within the context of the national and local (province) poverty conditions in the Philippines. The report examines government involvement in the provision of credit to low-income groups, and the importance and contributions of nongovernment microfinance providers. -

Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project Rehabilitation and Improvement of Liguron Access Road in Talakag, Bukidnon

Initial Environmental Examination January 2018 PHI: Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project Rehabilitation and Improvement of Liguron Access Road in Talakag, Bukidnon Prepared by Municipality of Talakag, Province of Bukidnon for the Asian Development Bank. i CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 30 November 2017 Year) The date of the currency equivalents must be within 2 months from the date on the cover. Currency unit – peso (PhP) PhP 1.00 = $ 0.01986 $1.00 = PhP 50.34 ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank BDC Barangay Development Council BUB Bottom-Up Budgeting CDORB Cagayan De Oro River Basin CNC Certificate of Non-Coverage CSC Construction Supervision Consultant CSO Civil Society Organization DED Detail Engineering Design DENR Department of Environment And Natural Resources DILG Department of Interior and Local Government DSWD Department of Social Welfare and Development ECA Environmentally Critical Area ECC Environmental Compliance Certificate ECP Environmentally Critical Project EHSM Environmental Health and Safety Manager EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EIS Environmental Impact Statement EMB Environmental Management Bureau ESS Environmental Safeguards Specialist GAD Gender and Development IEE Initial Environmental Examination INREMP Integrated Natural Resources and Environment Management Project IP Indigenous People IROW Infrastructure Right of Way LIDASAFA Liguron-Dagundalahon-Sagaran Farmers Association LGU Local Government Unit LPRAT Local Poverty Reduction Action Team MKaRNP Mt. Kalatungan Range Natural -

The Indigenous Peoples of Mt. Kitanglad Range Natural Park

Case study The Indigenous Peoples of Mt. Kitanglad Range Natural Park Ma. Easterluna Luz S. Canoy and Vellorimo J. Suminguit Ancestral home The Mt. Kitanglad Range Natural Park (MKRNP) in north- central Mindanao is home to three non-Christian and non- Muslim indigenous groups who refer to themselves as Talaandigs, Higaonons and Bukidnons. These indigenous inhabitants are known collectively as Bukidnon, a Bisayan word for “people from the mountain,” and they share a common culture and a common language, the Binukid. According to Talaandig tradition, most of Bukidnon was the land of the Talaandig, the people of the slopes (andig). When the coastal dwellers moved to the uplands, the Talaandig referred to them as “Higaonon” because the latter came from down the shore (higa). The Higaonon claim that their ancestors were coastal dwellers and were the original inhabitants of Misamis Oriental. However, the arrival of the dumagat (people from over the sea) during the Spanish times encouraged the natives to move up to the plateaus or uplands, which now belong mostly to Bukidnon province. The Higaonon today occupy communities north of Malaybalay down to the province of Misamis Oriental, while Talaandigs live in communities south of Malaybalay, around Lantapan and Talakag (Suminguit et al. 2001). According to tradition, as recounted in an epic tale called the olaging (a story chanted or narrated for hours), a common ancestor and powerful datu (chieftain) named Agbibilin sired four sons who became the ancestors of the present-day Manobo, Talaandig, Maranao, and Maguindanao. Tribal legend has it that Agbibilin named the mountain Kitanglad, from tanglad (lemon grass), a medicinal plant that was associated with the visible portion of the peak left when the mountain was almost submerged during the Great Deluge. -

Landcare in the Philippines STORIES of PEOPLE and PLACES

Landcare S TORIES OF PEOPLEAND PLACES Landcare in in the Philippines the Philippines STORIES OF PEOPLE AND PLACES Edited by Jenni Metcalfe www.aciar.gov.au 112 Landcare in the Philippines STORIES OF PEOPLE AND PLACES Edited by Jenni Metcalfe Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research ACIAR Monograph 112 i CanberraLandcare 2004 in the Philippines Edited by J. Metcalfe ACIAR Monograph 112 (printed version published in 2004) ACIAR MONOGRAPH SERIES This series contains the results of original research supported by ACIAR, or material deemed relevant to ACIAR’s research and development objectives. The series is distributed internationally, with an emphasis on developing countries This book has been produced by the Philippines – Australia Landcare project, a partnership between: • The Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) • World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) • SEAMEO Regional Center for Graduate Study and Research in Agriculture (SEARCA) • Agencia Española de Cooperacion Internacional (AECI) • Department of Primary Industries & Fisheries – Queensland Government (DPIF) • University of Queensland • Barung Landcare Association • Department of Natural Resources Mines and Energy – Queensland Government (DNRME) The Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) was established in June 1982 by an Act of the Australian Parliament. Its primary mandate is to help identify agricultural problems in developing countries and to commission collaborative research between Australian and developing -

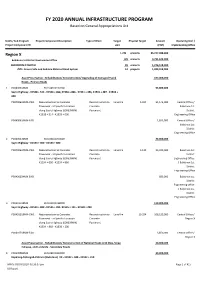

FY 2020 ANNUAL INFRASTRUCTURE PROGRAM Based on General Appropriations Act

FY 2020 ANNUAL INFRASTRUCTURE PROGRAM Based on General Appropriations Act UACS / Sub Program Project Component Description Type of Work Target Physical Target Amount Operating Unit / Project Component ID Unit (PHP) Implementing Office Region X 1,228 projects 36,227,088,000 Bukidnon 1st District Engineering Office 139 projects 4,791,103,000 BUKIDNON (FOURTH) 28 projects 1,274,518,000 OO1: Ensure Safe and Reliable National Road System 14 projects 1,029,018,000 Asset Preservation - Rehabilitation/ Reconstruction/ Upgrading of Damaged Paved 197,000,000 Roads - Primary Roads 1. P00400633MN 310104100197000 53,000,000 Sayre Highway - K1528 + 514 - K1529 + 000, K1530 + 896 - K1531 + 456, K1531 + 487 - K1533 + 000 P00400633MN-CW1 Reconstruction to Concrete Reconstruction to Lane Km 5.014 51,145,000 Central Office / Pavement - at Specific Locations Concrete Bukidnon 1st along Sayre Highway (S00639MN) Pavement District K1528 + 514 - K1533 + 000 Engineering Office P00400633MN-EAO 1,855,000 Central Office / Bukidnon 1st District Engineering Office 2. P00400634MN 310104100254000 34,000,000 Sayre Highway - K1534 + 000 - K1534 + 860 P00400634MN-CW1 Reconstruction to Concrete Reconstruction to Lane Km 3.132 33,320,000 Bukidnon 1st Pavement - at Specific Locations Concrete District along Sayre Highway (S00639MN) Pavement Engineering Office K1534 + 000 - K1534 + 860 / Bukidnon 1st District Engineering Office P00400634MN-EAO 680,000 Bukidnon 1st District Engineering Office / Bukidnon 1st District Engineering Office 3. P00401518MN 310104100198000 110,000,000 Sayre Highway - K1534 + 860 - K1535 + 091, K1535 + 121 - K1538 + 200 P00401518MN-CW1 Reconstruction to Concrete Reconstruction to Lane Km 10.294 106,150,000 Central Office / Pavement - at Specific Locations Concrete Region X along Sayre Highway (S00639MN) Pavement K1534 + 860 - K1538 + 200 P00401518MN-EAO 3,850,000 Central Office / Region X Asset Preservation - Rehabilitation/ Reconstruction of National Roads with Slips, Slope 20,000,000 Collapse, and Landslide - Secondary Roads 4. -

January 2012

January 2012 SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 PRC: Processing of LET & Renewal of IDs @ Marawi City PRC: LET Deadline of Filing Applications (01.06.2012 only) 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 PRC: PFRESPI PRC: PRC Planning PRC: LET Deadline of Oathtaking @ Butuan Conference @ PRC, Filing Applications @ all City Manila Regional Offices PRC: PRC Planning Conference @ PRC, Manila 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 PRC: Meeting w/ Real PRC: Information Drive PRC: Monitoring PRC: Monitoring PRC: Lecture on PRC State Practitioners @ on PRC Licensure @Butuan City @Butuan City updates & Licensure Pueblo de Oro System System @ Surigao City PRC: Monitoring @Butuan City 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 RTWPB: Meeting – RTWPB: Meeting – Consultation on Consultation on Livelihood Assistance Livelihood Assistance 29 30 31 RTWPB: RB cum Turnover of office & recognition… February 2012 SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY 1 2 3 4 Blessing of DOLE-10 Ozamiz Satellite Office 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 RTWPB: Green RTWPB: Green Productivity Productivity Training @ Training @ DMPI, Bugo DMPI, Bugo 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 PRC: Information Drive RCC Meeting PRC: Information Drive on PRC: Seminar on GAD @ on PRC Licensure System PRC Licensure System @ PRC, CDO @ MUST, CDO COC, CDO RTWPB: Training on Productivity @ LAMPCO, Balingasag 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 PRC: Information Drive RTWPB: Green PRC: Information Drive on RTWPB: Green POEA: SRA for United Global PRC: Renewal of PRC ID @ on PRC Licensure System Productivity Trainers’ PRC Licensure System @ Productivity Trainers’ @ 3 Sisters Dorm, Yacapin- Maramag @ Lourdes College, CDO Training Pilgrim, CDO Training Velez NCMB: POEA: SRA for United POEA: SRA for GBMLT @ PRC: Speaker on PAFTE POEA: SRA for United POEA: Job Fair @ BSU, PahalipaysaKabataangBik Global @ 3 Sisters Dorm, VIP Hotel Seminar @ Dynasty Court Global @ 3 Sisters Dorm, Malaybalay& Gov. -

Lay out Pdf.Pmd

Developing the Local Natural Resource Management Plan A Guide to Facilitators Delia C Catacutan Eduardo E Queblatin Caroline E Duque Lyndon J Arbes To more fully reflect our global reach, as well as our more balanced research and development agenda, we adopted a new brand name in 2002 ‘World Agroforestry Centre’. Our legal name - International Centre for Research in Agroforestry - remains unchanged, and so our acronym as a Future Harvest Centre remains the same. Views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the World Agroforestry Centre. All images remain the sole property of their source and may not be used for any purpose without written permission of the source. About this manual: Developing the Local Natural Resource Management Plan is a guide for facilitators and development workers, from both government and non-government organizations. The content of this guidebook outlines ICRAF’s experiences in working with different local governments in Mindanao in formulating and implementing NRM programs. Citation: Catacutan D, Queblatin E, Duque C, Arbes L. 2006. Developing the Local Natural Resource Management Plan: A Guide to Facilitators. Bukidnon, Philippines: World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF). ISBN: 978-971-93135-3-9 Copyright 2006 by the World Agroforestry Centre ICRAF - Philippines 2/F College of Forestry and Natural Resources Administration Building PO Box 35024, UPLB, College, Laguna 4031, Philippines Tel.: +63 49 536 2925; +63 49 536 7645 Fax: +63 49 536 4521 Email: [email protected] -

Enhancing the Role of Local Government Units in Environmental Regulation

Working Paper No. 04-06 ENHANCING THE ROLE OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT UNITS IN ENVIRONMENTAL REGULATION D.D. Elazegui, M.V.O. Espaldon, and A.T. Sumbalan Institute of Strategic Planning and Policy Studies (formerly Center for Policy and Development Studies) College of Public Affairs University of the Philippines Los Baños College, Laguna 4031 Philippines Telephone: (63-049) 536--3455 Fax: (63-049) 536-3637 E-mail address: [email protected] Homepage: www.uplb.edu.ph The ISPPS Working Paper series reports the results of studies conducted by the Institute faculty and staff. These have not been reviewed and are being circulated for the purpose of soliciting comments and suggestions. The views expressed in the paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of ISPPS and USAID through the SANREM CRSP/SEA.. Please send your comments to: The Director Institute of Strategic Planning & Policy Studies (formerly CPDS) College of Public Affairs University of the Philippines Los Baños College, Laguna 4031 Philippines ABOUT THE AUTHORS Ms. Dulce D Elazegui is a University Researcher, Institute of Strategic Planning and Policy Studies, College of Public Affairs, University of the Philippines Los Baños. Dr. Ma. Victoria Espaldon is an Associate Professor at the Department of Geography, University of the Philippines-Diliman, Quezon City. Dr. Antonio T. Sumbalan serves as Consultant to the Protected Area Management Board (PAMB) of the Mt. Kitanglad RangeNatural Park and Consultant to the Office of the Governor, Province of Bukidnon. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This publication was made possible through support provided by the Office of Agriculture, Bureau for Economic Growth, Agriculture and Trade, U.S.