Selective Bird Predation on the Peppered Moth: the Last Experiment of Michael Majerus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

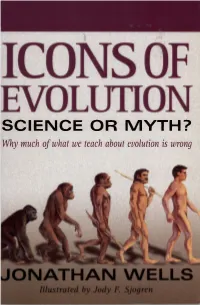

Why Much of What We Teach About Evolution Is Wrong/By Jonathan Wells

ON SCIENCE OR MYTH? Whymuch of what we teach about evolution is wrong Icons ofEvolution About the Author Jonathan Wells is no stranger to controversy. After spending two years in the U.S. Ar my from 1964 to 1966, he entered the University of California at Berkeley to become a science teacher. When the Army called him back from reser ve status in 1968, he chose to go to prison rather than continue to serve during the Vietnam War. He subsequently earned a Ph.D. in religious studies at Yale University, where he wrote a book about the nineteenth century Darwinian controversies. In 1989 he returned to Berkeley to earn a second Ph.D., this time in molecular and cell biology. He is now a senior fellow at Discovery Institute's Center for the Renewal of Science and Culture (www.discovery.org/ crsc) in Seattle, where he lives with his wife, two children, and mother. He still hopes to become a science teacher. Icons ofEvolution Science or Myth? Why Much oJWhat We TeachAbout Evolution Is Wrong JONATHAN WELLS ILLUSTRATED BY JODY F. SJOGREN IIIIDIDIREGNERY 11MPUBLISHING, INC. An EaglePublishing Company • Washington, IX Copyright © 2000 by Jonathan Wells All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or trans mitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including pho tocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. -

Peppered Moths and the Industrial Revolution: Barking up the Wrong Tree? by Avril M

NATIONAL CENTER FOR CASE STUDY TEACHING IN SCIENCE Peppered Moths and the Industrial Revolution: Barking up the Wrong Tree? by Avril M. Harder1, Janna R. Willoughby1,2, Jaqueline M. Doyle3 Part I – Hypotheses and Predictions The story of how Britain’s Industrial Revolution led to changes in peppered moth coloration is a classic, textbook ex- ample of evolution in action. You might even already be familiar with the plot and the findings of the main researcher of the phenomenon, H.B.D. Kettlewell. Although the peppered moth story has been told and re-told in thousands of biology classrooms, most narratives leave out an important bit of history: after Kettlewell published his results that described changes in morph population frequencies over time, many of his peers questioned the validity of his data. Your first task in this case study will be to put yourself in the place of one of Kettlewell’s contemporaries, evaluate his experimental methods, and decide whether his data support his assertions. Background Biston betularia is a medium-sized, nocturnal moth. Al- though the peppered moth is found across the world, some of the first research on this species was conducted in Great Britain. Before the Industrial Revolution, tree trunks in unpolluted areas were covered with lichens, and peppered moths with light colored wings were well camouflaged against this background (Figure 1). In this environment, light morphs vastly outnumbered dark morphs. During the Industrial Revolution, increasing air pollution led to the formation of acid rain and inhospitable conditions for the lichens. The death of the lichens combined with soot deposition on tree trunks led to an important environmen- tal shift for the moths. -

Did Kettlewell Commit Fraud? Re-Examining The

www.ssoar.info Did Kettlewell commit fraud? Re-examining the evidence Rudge, David Wÿss Postprint / Postprint Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: www.peerproject.eu Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Rudge, D. W. (2005). Did Kettlewell commit fraud? Re-examining the evidence. Public Understanding of Science, 14(3), 249-268. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662505052890 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter dem "PEER Licence Agreement zur This document is made available under the "PEER Licence Verfügung" gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zum PEER-Projekt finden Agreement ". For more Information regarding the PEER-project Sie hier: http://www.peerproject.eu Gewährt wird ein nicht see: http://www.peerproject.eu This document is solely intended exklusives, nicht übertragbares, persönliches und beschränktes for your personal, non-commercial use.All of the copies of Recht auf Nutzung dieses Dokuments. Dieses Dokument this documents must retain all copyright information and other ist ausschließlich für den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen information regarding legal protection. You are not allowed to alter Gebrauch bestimmt. Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments this document in any way, to copy it for public or commercial müssen alle Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise purposes, to exhibit the document in public, to perform, distribute auf gesetzlichen Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses or otherwise use the document in public. Dokument nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated Sie dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke conditions of use. vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. -

A Critique of Evolution Within Catholicism and Its

Approval Page J Donnelly i A CRITIQUE OF EVOLUTION WITHIN CATHOLICISM AND ITS SUBSEQUENT LINKS WITH FUNDAMENTAL CHRISTIANITY JOHN DONNELLY DIP.PHIL., B.D., H.DIP.ED., DIP. MISSION STUDIES, M.ED., FREEDOM BIBLE COLLEGE AND SEMINARY THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DOCTORAL DISSERTATION COMMITTEE IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DOCTOR OF THEOLOGY DEGREE J Donnelly ii CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements iv Thesis Statement v Introduction 1 PART ONE: EVOLUTION AND CATHOLICISM Chapter 1: A Short History of Evolution Theory 3 Chapter 2: Evolution and Catholicism – The Current Position 34 Chapter 3: Can Evolution Blend with Catholicism? 54 Chapter 4: Why Evolution Can Never Become Part of Catholic Doctrine 66 Chapter 5: Why Catholics Should Reject Evolution 91 PART TWO: SOME PHILOSOPHICAL CONSIDERATIONS AND EFFECTS OF EVOLUTION WITHIN CATHOLICISM Chapter 6: Why Evolution is Pseudoscience – Some Philosophical Considerations 105 Chapter 7: Dangerous Effects of Evolution 130 Chapter 8: A Lesson from History 140 PART THREE: CATHOLICISM AND BIBLICAL CRITICISM – A NEED TO RETURN TO THE SCRIPTURES Chapter 9: Moses and the reliability of the Pentateuch 167 Chapter 10: Two Different Accounts in Genesis? 175 PART FOUR: CONCLUSION Chapter 11: Evolution, Catholicism and Fundamentalism 184 Bibliography 212 J Donnelly iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe a huge debt of gratitude to the following people: Amy Joy Reilly who helped me with advice on editing; Vidis my wife who kept encouraging me when things were going slowly, enabling me to recommence; my parents John and Alice who also were a source of encouragement and who goaded me on; my pupils who were so interested in this theme and created even more enthusiasm in me; my daughter Clodagh who has never ceased to ask questions about evolution and kept me on my toes. -

The Peppered Moth and Industrial Melanism: Evolution of a Natural Selection Case Study

Heredity (2013) 110, 207–212 & 2013 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0018-067X/13 www.nature.com/hdy REVIEW The peppered moth and industrial melanism: evolution of a natural selection case study LM Cook1 and IJ Saccheri2 From the outset multiple causes have been suggested for changes in melanic gene frequency in the peppered moth Biston betularia and other industrial melanic moths. These have included higher intrinsic fitness of melanic forms and selective predation for camouflage. The possible existence and origin of heterozygote advantage has been debated. From the 1950s, as a result of experimental evidence, selective predation became the favoured explanation and is undoubtedly the major factor driving the frequency change. However, modelling and monitoring of declining melanic frequencies since the 1970s indicate either that migration rates are much higher than existing direct estimates suggested or else, or in addition, non-visual selection has a role. Recent molecular work on genetics has revealed that the melanic (carbonaria) allele had a single origin in Britain, and that the locus is orthologous to a major wing patterning locus in Heliconius butterflies. New methods of analysis should supply further information on the melanic system and on migration that will complete our understanding of this important example of rapid evolution. Heredity (2013) 110, 207–212; doi:10.1038/hdy.2012.92; published online 5 December 2012 Keywords: Biston betularia; carbonaria gene; mutation; predation; non-visual selection; migration INTRODUCTION EARLY EVIDENCE OF CHANGE The peppered moth Biston betularia (L.) and its melanic mutant will The peppered moth was the most diagrammatic example of the be familiar to readers of Heredity as an example of rapid evolutionary phenomenon of industrial melanism that came to be recognised in change brought about by natural selection in a changing environment, industrial and smoke-blackened parts of England in the mid-nine- evenifthedetailsofthestoryarenot.Infact,thedetailsarelesssimple teenth century. -

A Natural History of Ladybird Beetles M

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-11607-8 — A Natural History of Ladybird Beetles M. E. N. Majerus , Executive Editor H. E. Roy , P. M. J. Brown Frontmatter More Information A Natural History of Ladybird Beetles The Coccinellidae are a family of beetles, known variously as ladybirds or ladybugs. In Britain alone, some 46 species belong to the Coccinellidae family, although only 26 of these are recognisably ladybirds. Composed largely of Professor Michael Majerus’ lifetime work, and updated by two leading experts in the field, this book reveals intriguing insights into ladybird biology from a global perspective. The popularity of this insect group has been captured through societal and cultural considerations coupled with detailed descriptions of complex scientific processes, to provide a comprehensive and accessible overview of these charismatic insects. Bringing together many studies on ladybirds, this book has been organised into themes ranging from anatomy and physiology to ecology and evolution. This book is suitable for interested amateur enthusiasts and researchers involved with ladybirds, entomology and biological control. Michael E.N. Majerus (1954–2009) was Professor of Genetics in the Department of Genetics at the University of Cambridge and Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge. He was a world authority in his field, a tireless advocate of evolution and an enthusiastic educator of graduate and undergraduate students. Helen Roy is a Group Head and Principal Scientist at the NERC Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, where she leads zoological research within the Biological Records Centre (UK focus for terrestrial and freshwater species recording). She is an ecologist with a particular interest in the effects of environmental change on insect communities. -

Hdy199662.Pdf

Heredity 76 (1996) 424—425 The Genetical Society of Great Britain Book reviews Ladybirds. Michael E. N. Majerus. Harper Collins, I have a few minor quibbles with the illustrations. The London. 1994. Pp. 367. Price £14.99, paperback. ISBN 16 colour plates are a useful feature of the book but their 0 00 219935 1. quality is variable. Also, some of the line drawings, for example those in Chapter 15, have a rather 'home-spun' The New Naturalist series has a long and distinguished look to them. However, these slight reservations aside, history spanning more than 80 volumes and 50 years. In Ladybirds is a worthy addition to a distinguished tradition. that time it has contained monographs that have become Apart from keen naturalists wishing to increase their classics and covered specialist topics on most areas of understanding of an intriguing group of beetles, the book British natural history. From the outset it has been char- will also attract professional biologists as a reference work acterized by attractive presentation and good populariza- which is more complete and much more recent than Ivo tion by experts, both professional and amateur. Michael Hodek's Biology of Coccinellidae. Even university geneti- Majerus's Ladybirds is an excellent addition to the long cists looking for good ideas for project students might find tradition of the series. The author himself acknowledges it useful. the first book in the series, E. B. Ford's Butterflies, as the DAVID R. LEES inspiration in his schooldays towards an interest, and later School of Pure and Applied Biology a career, in entomology and genetics. -

The Peppered Moth: Decline of a Darwinian Disciple Michael E.N

The Peppered moth: decline of a Darwinian disciple Michael E.N. Majerus Reader in Evolution, Department of Genetics, University of Cambridge Delivered to the British Humanist Association, at the London School of Economics, on Darwin Day, 12th February 2004. {Text links to powerpoint presentation, with slides indicated by PP numbers} PP1 Introduction The rise of the melanic moth The rise of the black, carbonaria form of the peppered moth, Biston betularia, in response to changes in the environment caused by the industrial revolution in Britain, is probably the best known example of evolution in action. The reasons for the prominence of this example are three-fold. First, the rise was spectacular, occurred in the recent and well-documented past, and was timely, the first record of an individual of carbonaria being published by Edelston (1864), just five years after the Origin of Species (Darwin, 1859). Second, the difference in the forms had visual impact. Third, the major mechanism through which carbonaria rose is easy to both relate and understand. The story, in brief, is this. The non-melanic peppered moth is a white moth, liberally speckled with black scales (PP2). In 1848, a black form, f. carbonaria (PP3), was recorded in Manchester, and by 1895, 98% of the Mancunian population were black (PP4). The carbonaria form spread to many other parts of Britain, reaching high frequencies in industrial centres and regions downwind. In 1896, the Lepidopterist, J.W. Tutt, hypothesized that the increase in carbonaria, was the result of differential bird predation in polluted regions. Bernard Kettlewell obtained evidence in support of this hypothesis in the 1950s, with his predation experiments in polluted and unpolluted woodlands. -

MOTOR SYSTEMS Fect Orexactlytheoppositeeffect

Outside JEB iv the brain and anterior regions of the leech Keeping track of the literature intact, while simultaneously recording from isnʼt easy, so Outside JEB is a E21 and motor nerves involved in monthly feature that reports the swimming. The front part of the leech was most exciting developments in placed in sensory environments ranging experimental biology. Short from deep water (to enhance swimming) to articles that have been selected solid substrate (to stimulate crawling). In and written by a team of active the watery environment, E21 went back to research scientists highlight the enhancing swim episodes exclusively. But papers that JEB readers canʼt when the animal was faced with solid afford to miss. ground, E21 activation initiated and enhanced crawling. This suggests that instead of rigidly commanding downstream circuits to do a single behavior, E21 cells are commanding motor circuits to do an appropriate behavior based on sensory cues. MOTOR SYSTEMS This effect was completely masked in isolated preparations lacking brains. LEECH BRAIN ADDS FLEXIBILITY TO COMMAND How does the presence of the brain add NEURON OUTPUT flexibility to the circuits called into play by Spinal cords and equivalent structures in E21? The team measured how descending invertebrates (nerve cords) often generate inputs from the brain affect the strength of rhythmic motor patterns without inputs a synapse between E21 and a downstream from sensory systems or the brain. cell type known to ‘gate’ swimming. Gating Preparations that generate such ‘fictive cell activity is required to maintain swim rhythms’ have been used to uncover episodes, so when the E21-to-gating cell properties of motor circuits in many synapse is weak, triggered swim episodes animals. -

Discussion Questions Cookpaper

Evolution BIOL 4510/5450 Journal Club Activity Discussion Questions on Selective bird predation on the peppered moth: the last experiment of Michael Majerus. by L. M. Cook, B. S. Grant, I. J. Saccheri & J. Mallet (2012) Biology Letters 8, 609–612 <http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/8/4/609> 1. Define and explain the following terms and concepts as they apply to this paper. • Melanism • Cryptic coloration • Ecological genetics • Selective agent • Dominant allele • Selective sweep • Mark – recapture • Resting site • Interpolation • Randomization • Heterogeneity • Null hypothesis • Kettlewell • Mendelian locus • Bats • Typicals • Contingency • Supplementary material 2. What animals were used in this study and how were they obtained and maintained for these experiments? Why were these particular animals selected for this study? 3. What parameters were measured and analyzed in this study? Be prepared to explain how Fig. 1 displays these parameters. 4. Explain the use and/or purpose of the following in this study. • Netting ‘sleeves' • Binoculars • Branches • Light traps • Naturalistic densities • Eclosion • Probability • Non-selective predation 5. For the predation experiment, answer the following questions: (1) The specific goal or question that was addressed: (2) The basic experimental design (what was manipulated and what was measured to answer the question): (3) The independent variables that were manipulated and their units of measurement, where applicable: (4) The dependent variables that were measured in response to the manipulations and their units of measurement: (5) The main take home message or finding associated with the following: o Fig. 1: o Table 2: (Hint: Experimental results are often (but not always) plotted in terms of how the dependent variable (as plotted on the vertical or y-axis) depends on the independent variable (as plotted on the horizontal or x-axis). -

A Short History of the Theory of Evolution

Chapter 1: A Short History of Evolution Theory Despite having its heritage in ancient Greece, the theory of evolution was first brought to the consideration of the scientific world in the nineteenth century. The most carefully considered view of evolution was expressed by the French biologist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, in his Zoological Philosophy (1809). Lamarck thought that all living things were endowed with a vital force that steered them to evolve toward greater complexity. He also thought that organisms could impart to their offspring traits acquired during their lifetimes. As an example of this way of thinking, Lamarck suggested that the long neck of the giraffe evolved when a short-necked ancestor took to browsing on the leaves of trees instead of on grass. This evolutionary model of Lamarck's was invalidated by the discovery of the laws of genetic inheritance. In the middle of the twentieth century, the discovery of the structure of DNA revealed that the nuclei of the cells of living organisms possess very special genetic information, and that this could not be altered by ‘acquired traits’. In other words, during its lifetime, even though a giraffe managed to make its neck a few centimetres longer by extending it to upper branches, this trait would not pass to its offspring. In short, the Lamarckian view was simply refuted by scientific findings and went down in history as a faulty assumption. However, the evolutionary theory formulated by another natural scientist, who lived a couple of generations after Lamarck, proved to be more influential. This natural scientist was Charles Robert Darwin, and the theory he formulated is known as “Darwinism”. -

Experiment of Michael Majerus Selective Bird

Downloaded from rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org on January 25, 2013 Selective bird predation on the peppered moth: the last experiment of Michael Majerus L. M. Cook, B. S. Grant, I. J. Saccheri and J. Mallet Biol. Lett. 2012 8, doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2011.1136 first published online 8 February 2012 Supplementary data "Data Supplement" http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/suppl/2012/01/31/rsbl.2011.1136.DC1.ht ml References This article cites 16 articles, 4 of which can be accessed free http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/8/4/609.full.html#ref-list-1 Article cited in: http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/8/4/609.full.html#related-urls This article is free to access Subject collections Articles on similar topics can be found in the following collections behaviour (573 articles) ecology (598 articles) environmental science (124 articles) evolution (602 articles) Receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article - sign up in the box at the top Email alerting service right-hand corner of the article or click here To subscribe to Biol. Lett. go to: http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org/subscriptions Downloaded from rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org on January 25, 2013 Biol. Lett. (2012) 8, 609–612 took place in step with changing patterns of industrializ- doi:10.1098/rsbl.2011.1136 ation in Britain and elsewhere [3–5]. The melanic Published online 8 February 2012 ‘carbonaria’ morph is inherited via a dominant allele, Evolutionary biology C, at a single locus. The recessive c allele specifies the non-melanic black and white ‘typica’ form, while intermediate melanic ‘insularia’ alleles, inherited at the Selective bird predation on same locus, are dominant to typica and recessive to carbonaria.