The Peppered Moth and Industrial Melanism: Evolution of a Natural Selection Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directional Selection and Variation in Finite Populations

Copyright 0 1987 by the Genetics Society of America Directional Selection and Variation in Finite Populations Peter D. Keightley and ‘William G. Hill Institute of Animal Genetics, University of Edinburgh, West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3JN, Scotland Manuscript received April 12, 1987 Revised copy accepted July 16, 1987 ABSTRACT Predictions are made of the equilibrium genetic variances and responses in a metric trait under the joint effects of directional selection, mutation and linkage in a finite population. The “infinitesimal model“ is analyzed as the limiting case of many mutants of very small effect, otherwise Monte Carlo simulation is used. If the effects of mutant genes on the trait are symmetrically distributed and they are unlinked, the variance of mutant effects is not an important parameter. If the distribution is skewed, unless effects or the population size is small, the proportion of mutants that have increasing effect is the critical parameter. With linkage the distribution of genotypic values in the population becomes skewed downward and the equilibrium genetic variance and response are smaller as disequilibrium becomes important. Linkage effects are greater when the mutational variance is contributed by many genes of small effect than few of large effect, and are greater when the majority of mutants increase rather than decrease the trait because genes that are of large effect or are deleterious do not segregate for long. The most likely conditions for ‘‘Muller’s ratchet” are investi- gated. N recent years there has been much interest in the is attained more quickly in the presence of selection I production and maintenance of variation in pop- than in its absence, and is highly dependent on popu- ulations by mutation, stimulated by the presence of lation size. -

1 General Introduction

1 General Introduction If the karate-ka (student) shall walk the true path, first he will cast aside all preference. Tatsuo Shimabuku, Grand Master of Isshin-ryu Karate 1.1 The Importance of Insects ~30% of the plants we grow for food and materials. Because of their great numbers and diversity, insects Insects transmit some of these pathogens. While have a considerable impact on human life and indus- weeds can often reduce pest attack, they can also try, particularly away from cities and in the tropics. harbour the pest’s enemies or provide alternative On the positive side they form a large and irreplace- resources for the pest itself. Then in storage, insects, able part of the ecosystem, especially as pollinators mites, rodents and fungi cause a further 30% loss. of fruit and vegetable crops and, of course, many Apart from such biotic damage, severe physical con- wild plants (Section 8.2.1). They also have a place ditions such as drought, storms and flooding cause in soil formation (Section 8.2.4) and are being used additional losses. For example, under ideal field increasingly in ‘greener’ methods of pest control. conditions new wheat varieties (e.g. Agnote and Biological control using insects as predators and Humber) would give yields of ~16 tonnes/ha, but parasites of pest insects has been developed in the produce typically about half this under good hus- West for over a century, and much longer in China. bandry. Pre-harvest destruction due only to insects More recently integrated pest management (IPM) is 10–13% (Pimentel et al., 1984; Thacker, 2002). -

Looper Caterpillar- a Threat to Tea and Its Management

Circular No. 132 September 2010 Looper Caterpillar- a Threat to Tea and its Management By Dr. Mainuddin Ahmed Chief Scientific Officer Department of Pest Management & Mohammad Shameem Al Mamun Scientific Officer Entomology Division BANGLADESH TEA RESEARCH INSTITUTE SRIMANGAL-3210, MOULVIBAZAR An Organ of BANGLADESH TEA BOARD 171-172, BAIZID BOSTAMI ROAD NASIRABAD, CHITTAGONG Foreword Tea plant is subjected to the attack of pests and diseases. Tea pests are localized in tea growing area. In tea, today one is a minor and tomorrow it may be a major pest. Generally Looper caterpillar is a minor pest of tea. Actually it is a major shade tree pest. But now-a-days it is a major pest of tea in some areas. Already some of the tea estates faced the problem arising out of this pest. Under favourable environmental conditions it becomes a serious pest of tea and can cause substantial crop loss. The circular has covered almost all aspects of the pest ornately with significant information, which will be practically useful in managing the caterpillar. Particular emphasis has been given on Mechanical control option as a component of IPM strategies. With timely adoption and implementation of highlighted information in this circular, planters will be able to manage the caterpillar more efficiently in a cost-effective, environment friendly and sustainable way. September 2010 Mukul Jyoti Dutta Director in-charge Looper Caterpillar- a Threat to Tea and its Management Introduction The looper caterpillar, Biston suppressaria Guen. is one of the major defoliating pests of tea plantation in North-East India, causing heavy crop losses. -

Why Much of What We Teach About Evolution Is Wrong/By Jonathan Wells

ON SCIENCE OR MYTH? Whymuch of what we teach about evolution is wrong Icons ofEvolution About the Author Jonathan Wells is no stranger to controversy. After spending two years in the U.S. Ar my from 1964 to 1966, he entered the University of California at Berkeley to become a science teacher. When the Army called him back from reser ve status in 1968, he chose to go to prison rather than continue to serve during the Vietnam War. He subsequently earned a Ph.D. in religious studies at Yale University, where he wrote a book about the nineteenth century Darwinian controversies. In 1989 he returned to Berkeley to earn a second Ph.D., this time in molecular and cell biology. He is now a senior fellow at Discovery Institute's Center for the Renewal of Science and Culture (www.discovery.org/ crsc) in Seattle, where he lives with his wife, two children, and mother. He still hopes to become a science teacher. Icons ofEvolution Science or Myth? Why Much oJWhat We TeachAbout Evolution Is Wrong JONATHAN WELLS ILLUSTRATED BY JODY F. SJOGREN IIIIDIDIREGNERY 11MPUBLISHING, INC. An EaglePublishing Company • Washington, IX Copyright © 2000 by Jonathan Wells All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or trans mitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including pho tocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. -

Patterns and Power of Phenotypic Selection in Nature

Articles Patterns and Power of Phenotypic Selection in Nature JOEL G. KINGSOLVER AND DAVID W. PFENNIG Phenotypic selection occurs when individuals with certain characteristics produce more surviving offspring than individuals with other characteristics. Although selection is regarded as the chief engine of evolutionary change, scientists have only recently begun to measure its action in the wild. These studies raise numerous questions: How strong is selection, and do different types of traits experience different patterns of selection? Is selection on traits that affect mating success as strong as selection on traits that affect survival? Does selection tend to favor larger body size, and, if so, what are its consequences? We explore these questions and discuss the pitfalls and future prospects of measuring selection in natural populations. Keywords: adaptive landscape, Cope’s rule, natural selection, rapid evolution, sexual selection henotypic selection occurs when individuals with selection on traits that affect survival stronger than on those Pdifferent characteristics (i.e., different phenotypes) that affect only mating success? In this article, we explore these differ in their survival, fecundity, or mating success. The idea and other questions about the patterns and power of phe- of phenotypic selection traces back to Darwin and Wallace notypic selection in nature. (1858), and selection is widely accepted as the primary cause of adaptive evolution within natural populations.Yet Darwin What is selection, and how does it work? never attempted to measure selection in nature, and in the Selection is the nonrandom differential survival or repro- century following the publication of On the Origin of Species duction of phenotypically different individuals. -

Peppered Moths and the Industrial Revolution: Barking up the Wrong Tree? by Avril M

NATIONAL CENTER FOR CASE STUDY TEACHING IN SCIENCE Peppered Moths and the Industrial Revolution: Barking up the Wrong Tree? by Avril M. Harder1, Janna R. Willoughby1,2, Jaqueline M. Doyle3 Part I – Hypotheses and Predictions The story of how Britain’s Industrial Revolution led to changes in peppered moth coloration is a classic, textbook ex- ample of evolution in action. You might even already be familiar with the plot and the findings of the main researcher of the phenomenon, H.B.D. Kettlewell. Although the peppered moth story has been told and re-told in thousands of biology classrooms, most narratives leave out an important bit of history: after Kettlewell published his results that described changes in morph population frequencies over time, many of his peers questioned the validity of his data. Your first task in this case study will be to put yourself in the place of one of Kettlewell’s contemporaries, evaluate his experimental methods, and decide whether his data support his assertions. Background Biston betularia is a medium-sized, nocturnal moth. Al- though the peppered moth is found across the world, some of the first research on this species was conducted in Great Britain. Before the Industrial Revolution, tree trunks in unpolluted areas were covered with lichens, and peppered moths with light colored wings were well camouflaged against this background (Figure 1). In this environment, light morphs vastly outnumbered dark morphs. During the Industrial Revolution, increasing air pollution led to the formation of acid rain and inhospitable conditions for the lichens. The death of the lichens combined with soot deposition on tree trunks led to an important environmen- tal shift for the moths. -

Selection and Gene Duplication: a View from the Genome Comment Andreas Wagner

http://genomebiology.com/2002/3/5/reviews/1012.1 Minireview Selection and gene duplication: a view from the genome comment Andreas Wagner Address: Department of Biology, University of New Mexico, 167A Castetter Hall, Albuquerque, NM 817131-1091, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Published: 15 April 2002 Genome Biology 2002, 3(5):reviews1012.1–1012.3 reviews The electronic version of this article is the complete one and can be found online at http://genomebiology.com/2002/3/5/reviews/1012 © BioMed Central Ltd (Print ISSN 1465-6906; Online ISSN 1465-6914) Abstract reports Immediately after a gene duplication event, the duplicate genes have redundant functions. Is natural selection therefore completely relaxed after duplication? Does one gene evolve more rapidly than the other? Several recent genome-wide studies have suggested that duplicate genes are always under purifying selection and do not always evolve at the same rate. deposited research When a gene duplication event occurs, the duplicate genes synonymous (silent) nucleotide substitutions, Ks, and have redundant functions. Many deleterious mutations may second, of non-synonymous nucleotide substitutions (which then be harmless, because even if one gene suffers a muta- change the encoded amino acid), Ka (see Box 1). The ratio tion, the redundant gene copy can provide a back-up func- Ka/Ks provides a measure of the selection pressure to which tion. Put differently, after gene duplication - which can arise a gene pair is subject. If a duplicate gene pair shows a Ka/Ks through polyploidization (whole-genome duplication), non- ratio of about 1, that is, if amino-acid replacement substitu- homologous recombination, or through the action of retro- tions occur at the same rate as synonymous substitutions, transposons - one or both duplicates should experience then few or no amino-acid replacement substitutions have refereed research relaxed selective constraints that result in elevated rates of been eliminated since the gene duplication. -

Garden Moth Scheme Report 2017

Garden Moth Scheme Report 2017 Heather Young – April 2018 1 GMS Report 2017 CONTENTS PAGE Introduction 2 Top 30 Species 2017 3 Scientific Publications 4 Abundant and Widespread Species 8 Common or Garden Moths 11 Winter GMS 2017-18 15 Coordination Changes 16 GMS Annual Conference 16 GMS Sponsors 17 Links & Acknowledgements 18 Cover photograph: Peppered Moth (H. Young) Introduction The Garden Moth Scheme (GMS) welcomes participants from all parts of the United Kingdom and Ireland, and in 2017 received 360 completed recording forms, an increase of over 5% on 2016 (341). We have consistently received records from over 300 sites across the UK and Ireland since 2010, and now have almost 1 ½ million records in the GMS database. Several scientific papers using the GMS data have now been published in peer- reviewed journals, and these are listed in this report, with the relevant abstracts, to illustrate how the GMS records are used for research. The GMS is divided into 12 regions, monitoring 233 species of moth in every part of the UK and Ireland (the ‘Core Species’), along with a variable number of ‘Regional Species’. A selection of core species whose name suggests they should be found commonly, or in our gardens, is highlighted in this report. There is a round-up of the 2017-18 Winter Garden Moth Scheme, which attracted a surprisingly high number of recorders (102) despite the poor weather, a summary of the changes taking place in the GMS coordination team for 2018, and a short report on the 2018 Annual Conference, but we begin as usual with the Top 30 for GMS 2017. -

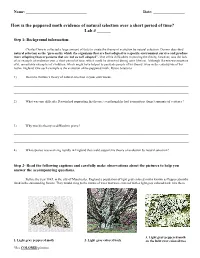

How Is the Peppered Moth Evidence of Natural Selection Over a Short Period of Time? Lab # ______

Name: _______________________________ Date: ________________ How is the peppered moth evidence of natural selection over a short period of time? Lab # ______ Step 1- Background information: Charles Darwin collected a large amount of facts to create the theory of evolution by natural selection. Darwin described natural selection as the “process by which the organisms that are best adapted to a specific environment survive and produce more offspring than organisms that are not as well adapted”. One of his difficulties in proving the theory, however, was the lack of an example of evolution over a short period of time, which could be observed during ones lifetime. Although Darwin was unaware of it, remarkable examples of evolution, which might have helped to persuade people of his theory, were in the countryside of his native England. One such example is the evolution of the peppered moth, Biston betularia. 1) Describe Darwin’s theory of natural selection in your own words. ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 2) What was one difficulty Darwin had supporting his theory, even though he had tremendous (large) amounts of evidence? ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 3) Why was his theory so -

Why Is the Story of the Peppered Moth So Famous and Important?

Connects with SciGen Unit L4 Teacher Tune-up Quick Content Refresher for Busy Professionals Why is the story of the peppered moth so famous and important? The story of Biston betularia, the peppered moth, is a staple of many textbooks on evolution. Briefly stated, some mostly light-colored moths got mostly dark colored over many generations; then they got light-colored again. So what’s the big deal? Why is the peppered moth such an evolutionary celebrity? Before 1800, most peppered moths were white, with a sprinkling of dark spots that give the moth its name. They were well camouflaged against lichens that grew on trees with light bark, which helped them avoid predatory birds. Throughout the nineteenth century, England’s industrial revolution saw the rise of steam power. Trains and steam-powered factories (the “dark Satanic Mills” of an 1808 poem by William Blake) burned coal and belched tons of soot into the environment. The black soot killed lichen and settled on the trees where the peppered moths rested. And generation by generation, the moths began to change. In 1811, someone found the first dark, nearly black, peppered moth. By the middle of the century, the frequency of melanism (dark coloration) in the peppered moths had risen dramatically. And by the end of the century, in large areas of England that were coated in dark industrial filth, nearly all peppered moths were dark. Along with changing landscapes and moths, another change was afoot. Naturalists had begun to speculate about something called evolution, based largely on evidence of ancient events: sequences in the fossil record, similarities among different species, vestigial structures in many organisms—that sort of thing. -

Natural Selection One of the Most Important Contributions Made to The

Natural Selection One of the most important contributions made to the science of evolution by Charles Darwin is the concept of natural selection. The idea that members of a species compete with each other for resources and that individuals that are better adapted to their lifestyle have a better chance of surviving to reproduce revolutionized the field of evolution, though it was not accepted until several decades after Darwin first proposed it. Today, natural selection forms the foundation for our understanding of how species change over time. Natural selection may act to change a trait in many ways. When environmental pressures favor the average form of the trait, selection is said to be stabilizing. Directional selection occurs when selection pressures favor one extreme of the trait distribution. Selection is disruptive when the average form of the trait is selected against while either extreme is unaffected. In addition to natural selection, there are two other types of selection. Sexual selection, which Darwin believed was distinct from natural selection, involves the selection of traits based on their role in courtship and mating. Artificial selection is the selective breeding of species by humans to increase desirable traits, though the traits do not necessarily have to confer greater fitness. Summary of Types of Natural Selection Natural selection can take many forms. To make talking about this easier, we will consider the distribution of traits across a population in using a graph. To the right is a normal curve. For example, if we were talking about height as a trait, we would see that without any selection pressure on this trait, the heights of individuals in a population would vary, with most individuals being of an average height and fewer being extremely short or extremely tall. -

Biston Betularia (Geometridae)

Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 49(1), 1995, 88-91 MELANISM HAS NOT EVOLVED IN JAPANESE BISTON BETULARIA (GEOMETRIDAE) Additional key words: peppered moth, form "carbonaria." No example of natural selection in Lepidoptera is more widely recognized than in dustrial melanism in Biston betu/aria (L.) (Geometridae). In Britain, the common name for the species is the peppered moth because the typical, pale adult is covered with white scales mottled with black splotches. It was the only form known until 1848 when the first melanic variant was discovered near Manchester, England. By the turn of the century about 98% of Manchester B. betu/aria populations were melanic, or "carbonaria" as the jet-black morph came to be known. Similar changes were recorded in the vicinities of other industrial cities throughout Britain. The primary reason for the rise in frequency of the carbona ria form was its enhanced cry psis in polluted woodlands blackened by industrial soot. Against the darker backgrounds, paler morphs were more conspicuous to predators. Because the replacements of paler forms by melanic variants coincided with the industrialization of various regions, the phenomenon was dubbed industrial melanism. For the most comprehensive review of the early history of industrial melanism in Biston betu/aria and other lepidopteran species, see Kettlewell (1973). Just over a century after the first melanic B. betu/aria was reported, the British gov ernment legislated the Clean Air Acts to enforce smokeless zones. Since that time Sir Cyril Clarke has documented a dramatic decline in the frequency of carbonaria from 93% to 23% between 1959 through 1993 on the Wirral Peninsula, just south of Liverpool (Clarke et al.