Kisimul Castle and the Origins of Hebridean Galley-Castles: Preliminary Thoughts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weekly Planning Schedule

Weekly Planning Schedule Week Commencing: 14 June 2021 Week Number: 24 CONTENTS 1 Valid Planning Applications Received 2 Delegated Officer Decisions 3 Committee Decisions 4 DPEA Appeal Decisions 5 Local Review Body (LRB) Appeal Decisions 6 Enforcement Matters 7 Land Reform (Scotland) Act Section 11 Access Exemption Applications 8 Other Planning Issues 9 Byelaw Exemption Applications 10 Byelaw Authorisation Applications In light of ongoing Covid-19 restrictions, we have continued to adapt how we deliver our planning service while our staff are still working remotely. Please see our planning services webpage for full details (https://www.lochlomond-trossachs.org/planning/coronavirus-covid-19-planning-services/) and follow @ourlivepark for future updates. Our offices remain closed to the public. All staff are continuing to work from home, with restricted access to some of our systems at times. In terms of phone calls, we would ask that you either email the case officer direct or [email protected] and we will call you back. We are now able to accept hard copy correspondence via post, however this remains under review depending on national and local restrictions. We would prefer all correspondence to be electronic where possible. Please email [email protected] National Park Authority Planning Staff If you have enquiries about new applications or recent decisions made by the National Park Authority you should contact the relevant member of staff as shown below. If they are not available, you may wish to leave -

Anke-Beate Stahl

Anke-Beate Stahl Norse in the Place-nam.es of Barra The Barra group lies off the west coast of Scotland and forms the southernmost extremity of the Outer Hebrides. The islands between Barra Head and the Sound of Barra, hereafter referred to as the Barra group, cover an area approximately 32 km in length and 23 km in width. In addition to Barra and Vatersay, nowadays the only inhabited islands of the group, there stretches to the south a further seven islands, the largest of which are Sandray, Pabbay, Mingulay and Bemeray. A number of islands of differing sizes are scattered to the north-east of Barra, and the number of skerries and rocks varies with the tidal level. Barra's physical appearance is dominated by a chain of hills which cuts through the island from north-east to south-west, with the peaks of Heaval, Hartaval and An Sgala Mor all rising above 330 m. These mountains separate the rocky and indented east coast from the machair plains of the west. The chain of hills is continued in the islands south of Barra. Due to strong winter and spring gales the shore is subject to marine erosion, resulting in a ragged coastline with narrow inlets, caves and natural arches. Archaeological finds suggest that farming was established on Barra by 3000 BC, but as there is no linguistic evidence of a pre-Norse place names stratum the Norse immigration during the ninth century provides the earliest onomastic evidence. The Celtic cross-slab of Kilbar with its Norse ornaments and inscription is the first traceable source of any language spoken on Barra: IEptir porgerdu Steinars dottur es kross sja reistr', IAfter Porgero, Steinar's daughter, is this cross erected'(Close Brooks and Stevenson 1982:43). -

2019 Cruise Directory

Despite the modern fashion for large floating resorts, we b 7 nights 0 2019 CRUISE DIRECTORY Highlands and Islands of Scotland Orkney and Shetland Northern Ireland and The Isle of Man Cape Wrath Scrabster SCOTLAND Kinlochbervie Wick and IRELAND HANDA ISLAND Loch a’ FLANNAN Stornoway Chàirn Bhain ISLES LEWIS Lochinver SUMMER ISLES NORTH SHIANT ISLES ST KILDA Tarbert SEA Ullapool HARRIS Loch Ewe Loch Broom BERNERAY Trotternish Inverewe ATLANTIC NORTH Peninsula Inner Gairloch OCEAN UIST North INVERGORDON Minch Sound Lochmaddy Uig Shieldaig BENBECULA Dunvegan RAASAY INVERNESS SKYE Portree Loch Carron Loch Harport Kyle of Plockton SOUTH Lochalsh UIST Lochboisdale Loch Coruisk Little Minch Loch Hourn ERISKAY CANNA Armadale BARRA RUM Inverie Castlebay Sound of VATERSAY Sleat SCOTLAND PABBAY EIGG MINGULAY MUCK Fort William BARRA HEAD Sea of the Glenmore Loch Linnhe Hebrides Kilchoan Bay Salen CARNA Ballachulish COLL Sound Loch Sunart Tobermory Loch à Choire TIREE ULVA of Mull MULL ISLE OF ERISKA LUNGA Craignure Dunsta!nage STAFFA OBAN IONA KERRERA Firth of Lorn Craobh Haven Inveraray Ardfern Strachur Crarae Loch Goil COLONSAY Crinan Loch Loch Long Tayvallich Rhu LochStriven Fyne Holy Loch JURA GREENOCK Loch na Mile Tarbert Portavadie GLASGOW ISLAY Rothesay BUTE Largs GIGHA GREAT CUMBRAE Port Ellen Lochranza LITTLE CUMBRAE Brodick HOLY Troon ISLE ARRAN Campbeltown Firth of Clyde RATHLIN ISLAND SANDA ISLAND AILSA Ballycastle CRAIG North Channel NORTHERN Larne IRELAND Bangor ENGLAND BELFAST Strangford Lough IRISH SEA ISLE OF MAN EIRE Peel Douglas ORKNEY and Muckle Flugga UNST SHETLAND Baltasound YELL Burravoe Lunna Voe WHALSAY SHETLAND Lerwick Scalloway BRESSAY Grutness FAIR ISLE ATLANTIC OCEAN WESTRAY SANDAY STRONSAY ORKNEY Kirkwall Stromness Scapa Flow HOY Lyness SOUTH RONALDSAY NORTH SEA Pentland Firth STROMA Scrabster Caithness Wick Welcome to the 2019 Hebridean Princess Cruise Directory Unlike most cruise companies, Hebridean operates just one very small and special ship – Hebridean Princess. -

Anne R Johnston Phd Thesis

;<>?3 ?3@@8393;@ 6; @53 6;;3> 530>623? 1/# *%%"&(%%- B6@5 ?=316/8 >343>3;13 @< @53 6?8/;2? <4 9A88! 1<88 /;2 @6>33 /OOG ># 7PJOSTPO / @JGSKS ?UDNKTTGF HPR TJG 2GIRGG PH =J2 CT TJG AOKVGRSKTY PH ?T# /OFRGWS &++& 4UMM NGTCFCTC HPR TJKS KTGN KS CVCKMCDMG KO >GSGCREJ.?T/OFRGWS,4UMM@GXT CT, JTTQ,$$RGSGCREJ"RGQPSKTPRY#ST"COFRGWS#CE#UL$ =MGCSG USG TJKS KFGOTKHKGR TP EKTG PR MKOL TP TJKS KTGN, JTTQ,$$JFM#JCOFMG#OGT$&%%'($'+)% @JKS KTGN KS QRPTGETGF DY PRKIKOCM EPQYRKIJT Norse settlement in the Inner Hebrides ca 800-1300 with special reference to the islands of Mull, Coll and Tiree A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Anne R Johnston Department of Mediaeval History University of St Andrews November 1990 IVDR E A" ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS None of this work would have been possible without the award of a studentship from the University of &Andrews. I am also grateful to the British Council for granting me a scholarship which enabled me to study at the Institute of History, University of Oslo and to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for financing an additional 3 months fieldwork in the Sunnmore Islands. My sincere thanks also go to Prof Ragni Piene who employed me on a part time basis thereby allowing me to spend an additional year in Oslo when I was without funding. In Norway I would like to thank Dr P S Anderson who acted as my supervisor. Thanks are likewise due to Dr H Kongsrud of the Norwegian State Archives and to Dr T Scmidt of the Place Name Institute, both of whom were generous with their time. -

Metering Point Address Data. Standardised Address Format

Metering Point Address Data Metering Point Address Data Standardised Address Format Ofgem 1 of 37 version 1.4 30/11/00 Metering Point Address Data Authors Andrew Dawson Technical Consultant, GB Information Management Peter Foster Data Consultant, GB Information Management Stephen Nugent Independent Consultant Revision History Revision Date Reason for Change 1.0 03/10/00 Draft circulation 1.1 16/10/00 GB Internal Issue 1.2 18/10/00 Draft circulation 1.3 01/11/00 Feedback on v.1.2 1.4 23/11/00 Review at ADWG Copyright © Ofgem. All rights reserved Ofgem 2 of 37 version 1.4 30/11/00 Metering Point Address Data Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................................................4 2 BS7666 PART 3 (PAF) ....................................................................................................................5 3 BS7666 PART 2 (NLPG) .................................................................................................................7 4 CURRENT STRUCTURE OF METERING POINT ADDRESS DATA.............................................8 5 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR STANDARDISED ADDRESS FORMAT.........................................12 6 ADDRESS FORMAT STANDARD.................................................................................................15 APPENDICES........................................................................................................................................19 APPENDIX A PAF ELEMENTS BREAKDOWN ........................................................................................20 -

2020 Cruise Directory Directory 2020 Cruise 2020 Cruise Directory M 18 C B Y 80 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−− 17 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−−

2020 MAIN Cover Artwork.qxp_Layout 1 07/03/2019 16:16 Page 1 2020 Hebridean Princess Cruise Calendar SPRING page CONTENTS March 2nd A Taste of the Lower Clyde 4 nights 22 European River Cruises on board MS Royal Crown 6th Firth of Clyde Explorer 4 nights 24 10th Historic Houses and Castles of the Clyde 7 nights 26 The Hebridean difference 3 Private charters 17 17th Inlets and Islands of Argyll 7 nights 28 24th Highland and Island Discovery 7 nights 30 Genuinely fully-inclusive cruising 4-5 Belmond Royal Scotsman 17 31st Flavours of the Hebrides 7 nights 32 Discovering more with Scottish islands A-Z 18-21 Hebridean’s exceptional crew 6-7 April 7th Easter Explorer 7 nights 34 Cruise itineraries 22-97 Life on board 8-9 14th Springtime Surprise 7 nights 36 Cabins 98-107 21st Idyllic Outer Isles 7 nights 38 Dining and cuisine 10-11 28th Footloose through the Inner Sound 7 nights 40 Smooth start to your cruise 108-109 2020 Cruise DireCTOrY Going ashore 12-13 On board A-Z 111 May 5th Glorious Gardens of the West Coast 7 nights 42 Themed cruises 14 12th Western Isles Panorama 7 nights 44 Highlands and islands of scotland What you need to know 112 Enriching guest speakers 15 19th St Kilda and the Outer Isles 7 nights 46 Orkney, Northern ireland, isle of Man and Norway Cabin facilities 113 26th Western Isles Wildlife 7 nights 48 Knowledgeable guides 15 Deck plans 114 SuMMER Partnerships 16 June 2nd St Kilda & Scotland’s Remote Archipelagos 7 nights 50 9th Heart of the Hebrides 7 nights 52 16th Footloose to the Outer Isles 7 nights 54 HEBRIDEAN -

The Scottish Isles – Whisky & Wildlife from the Hebrides to the Shetlands (Spitsbergen)

Focusing on the aspects the Scottish isles are famous for – THE SCOTTISH ISLES – WHISKY & WILDLIFE varied wildlife and superb distinctive whiskies, this cruise takes full advantage of the outer isles in May. We delve first into the FROM THE HEBRIDES TO THE SHETLANDS ‘whisky isle’ of Islay with its eight working distilleries creating unique, peaty drams that evokes the island’s terrain. In the (SPITSBERGEN) Victorian port of Oban, the distillery produces a very different style of whisky, whilst on the Isle of Mull, in the pretty tiny fishing port of Tobermory, the distillery dates from the 18th century. Those not interested in whisky will still be spoilt for choice in terms of wildlife, from the archipelago of the Treshnish Isles to lonely and remote St Kilda. In May, both destinations will have teeming colonies of nesting seabirds such as puffins, kittiwakes and gannets. Whether from the ship’s decks, explorer boat cruising, or on foot, we may also get to see otters, seals, sea eagles, and golden eagles. We may even hear a corncrake amongst the spring orchids in the fields of the Small Isles. Other highlights include a private hosted visit to one of Scotland’s most ancient and scenic castles. As guests of clan chieftain Sir Lachlan MacLean, we will enjoy a private evening visit at his clan home that has a history running back 800 years. We will see where Christianity arrived in Scotland from Ireland, and how Harris Tweed is created in the Outer Hebrides. 01432 507 280 (within UK) [email protected] | small-cruise-ships.com A city of industry and elegance, Belfast is the birthplace of the Titanic, as well as being the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland. -

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-Names and Society: Analysis of the Medieval Districts of Forsa and Moloros in the Parish of Torosay, Mull

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-names and society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/8224/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten:Theses http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Settlement-Names and Society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. Alasdair C. Whyte MA MRes Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Celtic and Gaelic | Ceiltis is Gàidhlig School of Humanities | Sgoil nan Daonnachdan College of Arts | Colaiste nan Ealain University of Glasgow | Oilthigh Ghlaschu May 2017 © Alasdair C. Whyte 2017 2 ABSTRACT This is a study of settlement and society in the parish of Torosay on the Inner Hebridean island of Mull, through the earliest known settlement-names of two of its medieval districts: Forsa and Moloros.1 The earliest settlement-names, 35 in total, were coined in two languages: Gaelic and Old Norse (hereafter abbreviated to ON) (see Abbreviations, below). -

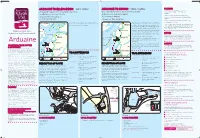

03. Arduaine 1600X1100.Indd 1 02/09/2015 15:43 Argyll Sea

ARDUAINE TO ELLENABEICH - 11km / 6Nm ARDUAINE TO CRINAN - 19km / 10Nm PARKING Argyll Sea The parking area provided at Arduaine is intended 56°13.841’N 5°32.937’W to 56°17.693’N 5°39.066’W 56°26.274’N 5°28.228’W to 56°05.186’N 5°32.848’W solely for paddlers making use of the Argyll Sea Grid Reference 801099 to 742174 Grid Reference 801099 to 794938 Kayak Trail. Arduaine is a sensitive access site, and respect must OS Landranger Map 49 & 55 OS Landranger Map 55 be shown for both the parking spaces available, and the local OS Explorer Map 359 OS Explorer Map 358 & 359 residents. Under no circumstances should any person park overnight, Easdale Sound. Pass the old ruined pier, and turn in behind the Once successfully navigated through, a course is set towards unless making use of the trail. ferry pier into a naturally formed bay. The gently sloping shoreline Liath-sgeir Mhòr, then passing between Eilean nan Coinean and There is a large car park at Ellenabeich. Continue right to the end in the far corner provides the egress point. the mainland, the longest stretch across open water. Continue of the village,following the signs, until you come to the car park into Loch Crinan, past Rubha Garbh-ard, Rudha na Mòine and at the western end. Please avoid parking in the small car park the stately Duntrune Castle into the mouth of the River Add. close to the ferry terminal. The egress point is a slipway (Grid Reference 794938) opposite Argyll Sea Kayak Trail Crinan Ferry, giving an easy portage up to the Crinan Canal. -

Join Us Aboard the Lady of Avenel for Sessions and Sail 2020 – Argyll

Join us aboard the Lady of Avenel for Sessions and Sail 2020 – Argyll This two-masted, Brigantine-rigged tall ship will be your home for the week as we step aboard in Oban and sail the waters south of Mull and the coast of Argyll and the islands. The ship will be your base for a voyage of exploration and music with sessions, workshops, sailing and more. See the spectacular Paps of Jura from the sea, feel the tide course through the Sound of Islay, visit Colonsay, Gigha and more. You will learn tunes from the rich local tradition under the guidance of some of Scotland’s best musicians in the bright saloon aboard Lady of Avenel; later, we will walk ashore to a local pub or village hall to play sessions with local musicians and meet the communities. Throughout the trip we will enjoy locally sourced food, beautifully prepared by our on-board chef. Some of our likely destinations are outlined overleaf. We look forward to having you join us! 1 Sessions and Sail - Nisbet Marine Services Ltd, Lingarth, Cullivoe, Yell, Shetland ZE2 9DD Tel: +44 (0)7775761149 Email: [email protected] Web: www.sessionsandsail.com If you are a keen musician playing at any level - whether beginner, intermediate or expert - with an interest in the traditional and folk music of Scotland, this trip is for you. No sailing experience is necessary, but those keen to participate will be encouraged to join in the sailing of the ship should they wish to, whether steering, helping set and trim the sails, or even climbing the mast for the finest view of all. -

Hebrides Explorer

UNDISCOVERED HEBRIDES NORTHBOUND EXPLORER Self Drive and Cycling Tours Highlights Stroll the charming streets of Stornoway. Walk the Bird of Prey trail at Loch Seaforth. Spot Otters & Golden eagles. Visit the incredible Callanish standing stones. Explore Sea Caves at Garry Beach. See the white sands of Knockintorran beach Visit the Neolithic chambered cairn at Barpa Langais. Explore the iconic Kisimul Castle. View Barra Seals at Seal Bay. Walk amongst Wildflowers and orchids on the Vatersay Machair. Buy a genuine Harris Tweed and try a dapple of pure Hebridean whiskey. Explore Harris’s stunning hidden beaches and spot rare water birds. Walk through the hauntingly beautiful Scarista graveyard with spectacular views. This self-guided tour of the spectacular Outer Hebrides from the South to the North is offered as a self-drive car touring itinerary or Cycling holiday. At the extreme edge of Europe these islands are teeming with wildlife and idyllic beauty. Hebridean hospitality is renowned, and the people are welcoming and warm. Golden eagles, ancient Soay sheep, Otters and Seals all call the Hebrides home. Walk along some of the most alluring beaches in Britain ringed by crystal clear turquoise waters and gleaming white sands. Take a journey to the abandoned archipelago of St Kilda, now a world heritage site and a wildlife sanctuary and walk amongst its haunting ruins. With a flourishing arts and music scene, and a stunning mix of ancient neolithic ruins and grand castles, guests cannot fail to be enchanted by their visit. From South to North - this self-drive / cycling Holiday starts on Mondays, Thursdays or Saturdays from early May until late September. -

Allasdale Dunes, Barra, Western Isles, Scotland

Wessex Archaeology Allasdale Dunes, Barra Western Isles, Scotland Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Ref: 65305 October 2008 Allasdale Dunes, Barra, Western Isles, Scotland Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Prepared on behalf of: Videotext Communications Ltd 49 Goldhawk Road LONDON W12 8QP By: Wessex Archaeology Portway House Old Sarum Park SALISBURY Wiltshire SP4 6EB Report reference: 65305.01 October 2008 © Wessex Archaeology Limited 2008, all rights reserved Wessex Archaeology Limited is a Registered Charity No. 287786 Allasdale Dunes, Barra, Western Isles, Scotland Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Contents Summary Acknowledgements 1 BACKGROUND..................................................................................................1 1.1 Introduction................................................................................................1 1.2 Site Location, Topography and Geology and Ownership ......................1 1.3 Archaeological Background......................................................................2 Neolithic.......................................................................................................2 Bronze Age ...................................................................................................2 Iron Age........................................................................................................4 1.4 Previous Archaeological Work at Allasdale ............................................5 2 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES.................................................................................6