Situating the Manifesto Between Command and Political Metamorphosis Matt Applegate Ph.D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1990 NGA Annual Meeting

BARLOW & JONES P.O. BOX 160612 MOBILE, ALABAMA 36616 (205) 476-0685 ~ 1 2 ACHIEVING EDUCATIONAL EXCELLENCE 3 AND ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY 4 5 National Governors' Association 6 82nd Annual Meeting Mobile, Alabama 7 July 29-31, 1990 8 9 10 11 12 ~ 13 ..- 14 15 16 PROCEEDINGS of the Opening Plenary Session of the 17 National Governors' Association 82nd Annual Meeting, 18 held at the Mobile Civic Center, Mobile, Alabama, 19 on the 29th day of July, 1990, commencing at 20 approximately 12:45 o'clock, p.m. 21 22 23 ".~' BARLOW & JONES P.O. BOX 160612 MOBILE. ALABAMA 36616 (205) 476-0685 1 I N D E X 2 3 Announcements Governor Branstad 4 Page 4 5 6 Welcoming Remarks Governor Hunt 7 Page 6 8 9 Opening Remarks Governor Branstad 10 Page 7 11 12 Overview of the Report of the Task Force on Solid Waste Management 13 Governor Casey Governor Martinez Page 11 Page 15 14 15 Integrated Waste Management: 16 Meeting the Challenge Mr. William D. Ruckelshaus 17 Page 18 18 Questions and Discussion 19 Page 35 20 21 22 23 2 BARLOW & JONES P.O. BOX 160612 MOBILE, ALABAMA 36616 (205) 476-0685 1 I N D E X (cont'd) 2 Global Environmental Challenges 3 and the Role of the World Bank Mr. Barber B. Conable, Jr. 4 Page 52 5 Questions and Discussion 6 Page 67 7 8 Recognition of NGA Distinguished Service Award Winners 9 Governor Branstad Page 76 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 3 BARLOW & JONES P.O. -

POLL RESULTS: Congressional Bipartisanship Nationwide and in Battleground States

POLL RESULTS: Congressional Bipartisanship Nationwide and in Battleground States 1 Voters think Congress is dysfunctional and reject the suggestion that it is effective. Please indicate whether you think this word or phrase describes the United States Congress, or not. Nationwide Battleground Nationwide Independents Battleground Independents Dysfunctional 60 60 61 64 Broken 56 58 58 60 Ineffective 54 54 55 56 Gridlocked 50 48 52 50 Partisan 42 37 40 33 0 Bipartisan 7 8 7 8 Has America's best 3 2 3 interests at heart 3 Functioning 2 2 2 3 Effective 2 2 2 3 2 Political frustrations center around politicians’ inability to collaborate in a productive way. Which of these problems frustrates you the most? Nationwide Battleground Nationwide Independents Battleground Independents Politicians can’t work together to get things done anymore. 41 37 41 39 Career politicians have been in office too long and don’t 29 30 30 30 understand the needs of regular people. Politicians are politicizing issues that really shouldn’t be 14 13 12 14 politicized. Out political system is broken and doesn’t work for me. 12 15 12 12 3 Candidates who brand themselves as bipartisan will have a better chance of winning in upcoming elections. For which candidate for Congress would you be more likely to vote? A candidate who is willing to compromise to A candidate who will stay true to his/her get things done principles and not make any concessions NationwideNationwide 72 28 Nationwide Nationwide Independents Independents 74 26 BattlegroundBattleground 70 30 Battleground Battleground IndependentsIndependents 73 27 A candidate who will vote for bipartisan A candidate who will resist bipartisan legislation legislation and stick with his/her party NationwideNationwide 83 17 Nationwide IndependentsNationwide Independents 86 14 BattlegroundBattleground 82 18 Battleground BattlegroundIndependents Independents 88 12 4 Across the country, voters agree that they want members of Congress to work together. -

Becoming-Other: Foucault, Deleuze, and the Political Nature of Thought Vernon W

Philosophy Faculty Publications Philosophy 4-2014 Becoming-Other: Foucault, Deleuze, and the Political Nature of Thought Vernon W. Cisney Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/philfac Part of the Philosophy of Mind Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Cisney, Vernon W. "Becoming-Other: Foucault, Deleuze, and the Nature of Thought." Foucault Studies 17 Special Issue: Foucault and Deleuze (April 2014). This is the publisher's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/philfac/37 This open access article is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Becoming-Other: Foucault, Deleuze, and the Political Nature of Thought Abstract In this paper I employ the notion of the ‘thought of the outside’ as developed by Michel Foucault, in order to defend the philosophy of Gilles Deleuze against the criticisms of ‘elitism,’ ‘aristocratism,’ and ‘political indifference’—famously leveled by Alain Badiou and Peter Hallward. First, I argue that their charges of a theophanic conception of Being, which ground the broader political claims, derive from a misunderstanding of Deleuze’s notion of univocity, as well as a failure to recognize the significance of the concept of multiplicity in Deleuze’s thinking. From here, I go on to discuss Deleuze’s articulation of the ‘dogmatic image of thought,’ which, insofar as it takes ‘recognition’ as its model, can only ever think what is already solidified and sedimented as true, in light of existing structures and institutions of power. -

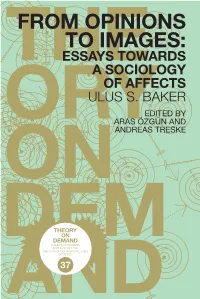

From Opinions to Images: Essays Towards a Sociology of Affects Ulus S

FROM OPINIONS TO IMAGES: ESSAYS TOWARDS A SOCIOLOGY OF AFFECTS ULUS S. BAKER EDITED BY ARAS ÖZGÜN AND ANDREAS TRESKE A SERIES OF READERS PUBLISHED BY THE INSTITUTE OF NETWORK CULTURES ISSUE NO.: 37 FROM OPINIONS TO IMAGES: ESSAYS TOWARDS A SOCIOLOGY OF AFFECTS ULUS S. BAKER EDITED BY ARAS ÖZGÜN AND ANDREAS TRESKE FROM OPINIONS TO IMAGES 2 Theory on Demand #37 From Opinions to Images: Essays Towards a Sociology of Affects Ulus S. Baker Edited by Aras Özgün and Andreas Treske Cover design: Katja van Stiphout Design and EPUB development: Eleni Maragkou Published by the Institute of Network Cultures, Amsterdam, 2020 ISBN print-on-demand: 978-94-92302-66-3 ISBN EPUB: 978-94-92302-67-0 Contact Institute of Network Cultures Phone: +31 (0)20 595 1865 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.networkcultures.org This publication is available through various print on demand services. EPUB and PDF edi- tions are freely downloadable from our website: http://www.networkcultures.org/publications. This publication is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommer- cial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International. FROM OPINIONS TO IMAGES 3 Cover illustration: Diagram of the signifier from Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 1987. 4 THEORY ON DEMAND CONTENTS PASSING THROUGH THE WRITINGS OF ULUS BAKER 5 1. A SOCIOLOGY OF AFFECTS 9 2. WHAT IS OPINION? 13 3. WHAT IS AN AFFECT? 59 4. WHAT IS AN IMAGE? 86 5. TOWARDS A NEO-VERTOVIAN SENSIBILITY OF AFFECTS 160 6. ON CINEMA AND ULUS BAKER 165 BIBLIOGRAPHY 180 BIOGRAPHIES 187 FROM OPINIONS TO IMAGES 5 We have lived at least one century within the idea of opinion which determined some of the major themes in social sciences.. -

Kleinherenbrink's Externality Thesis and Deleuze's Machine Ontology

Cosmos and History: The Journal of Natural and Social Philosophy, vol. 16, no. 1, 2020 REVIEW ARTICLE AGAINST THE VIRTUAL: KLEINHERENBRINK’S EXTERNALITY THESIS AND DELEUZE’S MACHINE ONTOLOGY Ekin Erkan ABSTRACT: Reviewing Arjen Kleinherenbrink’s recent book, Against Continuity: Gilles Deleuze's Speculative Realism (2019), this paper undertakes a detailed review of Kleinherenbrink’s fourfold “externality thesis” vis-à-vis Deleuze’s machine ontology. Reading Deleuze as a philosopher of the actual, this paper renders Deleuzean syntheses as passive contemplations, pulling other (passive) entities into an (active) experience and designating relations as expressed through contraction. In addition to reviewing Kleinherenbrink’s book (which argues that the machine ontology is a guiding current that emerges in Deleuze’s work after Difference and Repetition) alongside much of Deleuze’s oeuvre, we relate and juxtapose Deleuze’s machine ontology to positions concerning externality held by a host of speculative realists. Arguing that the machine ontology has its own account of interaction, change, and novelty, we ultimately set to prove that positing an ontological “cut” on behalf of the virtual realm is unwarranted because, unlike the realm of actualities, it is extraneous to the structure of becoming—that is, because it cannot be homogenous, any theory of change vis-à-vis the virtual makes it impossible to explain how and why qualitatively different actualities are produced. KEYWORDS: Ontology; Speculative Philosophy; Deleuze; Object-Oriented Ontology; Speculative Realism; Machine Ontology www.cosmosandhistory.org 492 EKIN ERKAN 493 § INTRODUCTION Following Arjen Kleinherenbrink’s Against Continuity: Gilles Deleuze’s Speculative Realism (2019)—arguably one of the closest and most rigorous secondary readings of Deleuze’s oeuvre—this paper seeks to demonstrate how any relation between machines immediately engenders a new machine, accounting for machinic circuits of activity where becoming, or processes of generation, are always necessarily irreducible to their generators. -

The Virtual and the Real

The Virtual and the Real David J. Chalmers How real is virtual reality? The most common view is that virtual reality is a sort of fictional or illusory reality, and that what goes in in virtual reality is not truly real. In Neuromancer, William Gibson famously said that cyberspace (meaning virtual reality) is a “consensual hallucination”. It is common for people discussing virtual worlds to contrast virtual objects with real objects, as if virtual objects are not truly real. I will defend the opposite view: virtual reality is a sort of genuine reality, virtual objects are real objects, and what goes on in virtual reality is truly real. We can get at the issue via a number of questions. (1) Are virtual objects, such as the avatars and tools found in a typical virtual world, real or fictional? (2) Do virtual events, such as a trek through a virtual world, really take place? (3) When we perceive virtual worlds by having immer- sive experiences of a world surrounding us, are our experiences illusory? (4) Are experiences in a virtual world as valuable as experiences in a nonvirtual world? Here we can distinguish two broad packages of views. A package that we can call virtual realism (loosely inspired by Michael Heim’s 1998 book of the same name) holds:1 (1) Virtual objects really exist. (2) Events in virtual reality really take place. (3) Experiences in virtual reality are non-illusory. 0Forthcoming in Disputatio. Thanks to audiences at Arizona, the Australasian Association of Philosophy, Brooklyn Library, Glasgow, Harvard, Hay-on-Wye, La Guardia College, NYU, Skidmore, Stanford, and Sun Valley, and espe- cially at the Petrus Hispanus Lectures at the University of Lisbon. -

Conservatives on Madison Avenue: Political Advertising and Direct Marketing in the 1950S

NANZAN REVIEW OF AMERICAN STUDIES Volume 41 (2019): 3-25 Conservatives on Madison Avenue: Political Advertising and Direct Marketing in the 1950s MORIYAMA Takahito * This article investigates how urban consumerism affected the rise of modern American conservatism by focusing on anticommunists’ political advertising in New York City during the 1950s. The advertising industry developed the new tactic of direct marketing in the post-World War II period and, over the years, several political activists adopted this new marketing technique for political campaigns. Direct mail, a product of the new marketing, was a personalized medium that built up a database of personal information and sent suitable messages to individuals, instead of standardized information to the masses. The medium was especially significant for conservatives to disseminate their ideology to prospective supporters across the country in the 1950s when the conservati ve media establishment did not exist. This research explores the development of the American right in urban areas by analyzing the role of direct mail in the conservative movement. The postwar era witnessed the rise of modern American conservatism as a political movement. Following World War II, anticommunism became widespread among Americans and the United States was confronted with communism abroad, whereas in domestic politics right-wing movements, such as McCarthyism, attacked liberalism. The New Deal had angered many Americans prior to the 1950s. Frustrated with government regulations since the 1930s, some businesspeople acclaimed the free enterprise system and individual liberties as the American ideal; several intellectuals and religious figures criticized the decline of traditional values in modern society; and white Southerners were adamant in preventing the federal government from interfering in the Jim Crow laws. -

Preferences for Bipartisanship in the American Electorate Laurel

Compromise vs. Compromises: Preferences for Bipartisanship in the American Electorate Laurel Harbridge* Assistant Professor, Northwestern University Faculty Fellow, Institute for Policy Research [email protected] Scott Hall 601 University Place Evanston, IL 60208 (847) 467-1147 Neil Malhotra Associate Professor, Stanford Graduate School of Business [email protected] 655 Knight Way Stanford, CA 94035 (408) 772-7969 Brian F. Harrison PhD Candidate, Northwestern University [email protected] Scott Hall 601 University Place Evanston, IL 60208 * Corresponding author. We thank Time-Sharing Experiments in the Social Sciences (TESS) for providing the majority of the financial support of this project. TESS is funded by the National Science Foundation (SES- 0818839). A previous version of this paper was scheduled for presentation at the 2012 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association. Abstract Public opinion surveys regularly assert that Americans want political leaders to work together and to engage in bipartisan compromise. If so, why has Congress become increasingly acrimonious even though the American public wants it to be “bipartisan”? Many scholars claim that this is simply a breakdown of representation. We offer another explanation: although people profess support for “bipartisanship” in an abstract sense, what they desire procedurally out of their party representatives in Congress is to not compromise with the other side. To test this argument, we conduct two experiments in which we alter aspects of the political context to see how people respond to parties (not) coming together to achieve broadly popular public policy goals. We find that citizens’ proclaimed desire for bipartisanship in actuality reflects self-serving partisan desires. -

The XXI Century Socialism in the Context of the New Latin American Left Civilizar

Civilizar. Ciencias Sociales y Humanas ISSN: 1657-8953 [email protected] Universidad Sergio Arboleda Colombia Ramírez Montañez, Julio The XXI century socialism in the context of the new Latin American left Civilizar. Ciencias Sociales y Humanas, vol. 17, núm. 33, julio-diciembre, 2017, pp. 97- 112 Universidad Sergio Arboleda Bogotá, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=100254730006 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Civilizar Ciencias Sociales y Humanas 17 (33): 97-112, Julio-Diciembre de 2017 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22518/16578953.902 The XXI century socialism in the context of the new Latin American left1 El socialismo del siglo XXI en el contexto de la nueva izquierda latinoamericana Recibido: 27 de juniol de 2016 - Revisado: 10 de febrero de 2017 – Aceptado: 10 de marzo de 2017. Julio Ramírez Montañez2 Abstract The main purpose of this paper is to present an analytical approach of the self- proclaimed “new socialism of the XXI Century” in the context of the transformations undertaken by the so-called “Bolivarian revolution”.The reforms undertaken by referring to the ideology of XXI century socialism in these countries were characterized by an intensification of the process of transformation of the state structure and the relations between the state and society, continuing with the nationalization of sectors of the economy, the centralizing of the political apparatus of State administration. -

97 Giulio Piatti

S&F_n. 17_2017 GIULIO PIATTI «THE POWERFUL, NON‐ORGANIC LIFE WHICH GRIPS THE WORLD». VITALISM AND ONTOLOGY IN GILLES DELEUZE 1. Intro 2. Vitalistic turn. Deleuze’s Bergsonism 3. Ontological framework: virtuality, becoming, univocity 4. From organic to inorganic. Gothic avatar, crystallization, metallurgy 5. Conclusion. Life of things, death of “person” ABSTRACT: «THE POWERFUL, NON‐ORGANIC LIFE WHICH GRIPS THE WORLD». VITALISM AND ONTOLOGY IN GILLES DELEUZE It is well known that Gilles Deleuze is the heir of a complex vitalistic tradition, beginning with Henri Bergson’s Creative Evolution and spanning through an important part of 20th century French philosophy. According to this line of thought, philosophy has to sharpen its vision in order to grasp the irreducible nature of the living. On one hand Deleuze seems to explicitly follow these intuitions, on the other though he strives to find a viable ontological framework for an actual philosophy of life, reaffirming the Nietzschean notion of being as becoming, the Bergsonian virtual coexistence of memory and Scotist univocity of the being. Through such operation, Deleuze actually seems to distance himself from a simply vitalistic approach, and to build instead an original metaphysics that understands life as a powerful inorganic force crossing all levels of reality. The organic, thus, is what traps and diverts (détourne) this impersonal and germinal life. Aim of the presentation is to clarify the originality of Deleuze’s vitalistic ontology and point to its ambiguities and debts towards other philosophical traditions. Even if Deleuze apparently overturns his vitalistic roots, it is nevertheless undeniable that the vital domain will engage him throughout all of his work. -

The Relevance of Michel Serres's Idea of Bodily Hominescence for A

Philosophy Study, February 2020, Vol. 10, No. 2, 119-126 doi: 10.17265/2159-5313/2020.02.003 D DAVID PUBLISHING The Relevance of Michel Serres’s Idea of Bodily Hominescence for a Convergence of Posthumanism and Transhumanism: A Trans/Posthuman Body Orsola Rignani University of Florence, Florence, Italy Faced with the challenge of arguments about the relation of post-, and trans-humanism, putting forth questions on their “antagonism”, or “convergence”, I propose to (re-)evaluate/highlight the relevance of the thinking of Michel Serres for posthuman debates. It specifically seems to me that Serresian idea of bodily hominescence can be read as a suggestion of “convergence” of post- and trans-humanism. Starting from the assumption that the body is a crucial node of both of them in that its consideration by one and the other marks a major front of their divergence (tool body according to transhumanism, dimensional body according to posthumanism), I seem to grasp, within the Serresian theme of the hominescent body as totipotent/virtual, the idea of bodily virtuality as a point of their convergence. Following Serres’s argument that, due to its virtuality/potentiality (intended as the totality of the possibilities), the body, though always involved in (technological) hybridization processes, is difficult to be artificially reproduced and to be reduced to information, I assume virtuality as an “operational concept” capable of “producing” convergence of post- and trans-humanism. Such a concept allows me, in fact, to read the body (re-)invested, by technology as an infiltrative agent, of a dimensional role as hybridizer (and in this sense normalized). -

WHY COMPETITION in the POLITICS INDUSTRY IS FAILING AMERICA a Strategy for Reinvigorating Our Democracy

SEPTEMBER 2017 WHY COMPETITION IN THE POLITICS INDUSTRY IS FAILING AMERICA A strategy for reinvigorating our democracy Katherine M. Gehl and Michael E. Porter ABOUT THE AUTHORS Katherine M. Gehl, a business leader and former CEO with experience in government, began, in the last decade, to participate actively in politics—first in traditional partisan politics. As she deepened her understanding of how politics actually worked—and didn’t work—for the public interest, she realized that even the best candidates and elected officials were severely limited by a dysfunctional system, and that the political system was the single greatest challenge facing our country. She turned her focus to political system reform and innovation and has made this her mission. Michael E. Porter, an expert on competition and strategy in industries and nations, encountered politics in trying to advise governments and advocate sensible and proven reforms. As co-chair of the multiyear, non-partisan U.S. Competitiveness Project at Harvard Business School over the past five years, it became clear to him that the political system was actually the major constraint in America’s inability to restore economic prosperity and address many of the other problems our nation faces. Working with Katherine to understand the root causes of the failure of political competition, and what to do about it, has become an obsession. DISCLOSURE This work was funded by Harvard Business School, including the Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness and the Division of Research and Faculty Development. No external funding was received. Katherine and Michael are both involved in supporting the work they advocate in this report.