The Industrial Archaeology of Cheshire : an Overview Nevell, MD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reliques of the Anglo-Saxon Churches of St. Bridget and St. Hildeburga, West Kirby, Cheshire

RELIQUES OF THE ANGLO-SAXON CHURCHES OF ST. BRIDGET AND ST. HILDEBURGA, WEST KIRKBY, CHESHIRE. By Henry Ecroyd Smith. (BEAD IST DEOBMBEB, 1870.) THE Parish of West Kirkby (now West Kirby), lying 18 miles N.W. of Chester city, is one of the most important in the hundred of Wirral, and occupies the whole of its north western angle. Dr. Ormerod describes its first quarter as comprising the townships of West Kirkby and Newton-cum- Larton, with that of Grange, Great Caldey or Caldey Grange ; second, the townships of Frankby and Greasby ; third, those of Great and Little Meols, with Hoose ; fourth, the township of Little Caldey.* Originally Kirklye, or, settlement at the Church, it became " West Kirkby," to distinguish it from "Kirkby-in-Walley," at the opposite corner of the peninsula of Wirral, now com monly known as Wallasey. Each of these extensive parishes possessed two Churches, those of Wallasey lying the one in Kirkby-in-Walley, the other on the Leasowes and near the sea, which ultimately destroyed it and engulphed the site together with that of its burial-ground. For further informa tion on this head, Bishop Gastrell's " Notitia," Dr. Ormerod's " History of the County,"\ and Lyson's " Cheshire,"% may be consulted. Gastrell's Notitia. The last now simply bears the name of Caldy. t II, 360. Heading of Moretou. { Page 807. 14 The Churches of West Kirkby were situate, the parish Church at the town proper, the other, a Chapel of Ease, upon Saint Hildeburgh's Eye, i.e., the island of St. Hildeburga, which had become insulated through the same potent influence which had wrecked the Chapel, as Bishop Gastrell calls it, upon the Leasowe shore. -

Advisory Visit River Bollin, Styal Country Park, Cheshire February

Advisory Visit River Bollin, Styal Country Park, Cheshire February 2010 1.0 Introduction This report is the output of a site visit undertaken by Tim Jacklin of the Wild Trout Trust to the River Bollin, Cheshire on 19th February 2010. Comments in this report are based on observations on the day of the site visit and discussions with Kevin Nash (Fisheries Technical Specialist) and Andy Eaves (Fisheries Technical Officer) of the Environment Agency (EA), North West Region (South Area). Normal convention is applied throughout the report with respect to bank identification, i.e. the banks are designated left hand bank (LHB) or right hand bank (RHB) whilst looking downstream. 2.0 Catchment / Fishery Overview The River Bollin is 49 km long and rises in the edge of Macclesfield Forest, flowing west to join the River Mersey (Manchester Ship Canal) near Lymm. The River Dean is the major tributary of the Bollin, and the catchment area totals 273 km2. The section of river visited flows through Styal Country Park, downstream of Quarry Bank Mill, and is owned by the National Trust. A previous Wild Trout Trust visit was carried out further downstream at the National Trust property at Dunham Massey. The Bollin falls within the remit of the Mersey Life Project which aims to carry out a phased programme of river restoration, initially focussing on the non-tidal section of the River Mersey, the River Bollin and River Goyt (http://www.environment-agency.gov.uk/homeandleisure/wildlife/102362.aspx). The construction of fish passes on Heatley and Bollington Mill weirs in the lower Bollin catchment means it is now possible for migratory species (e.g. -

EDUCATION of POOR GIRLS in NORTH WEST ENGLAND C1780 to 1860: a STUDY of WARRINGTON and CHESTER by Joyce Valerie Ireland

EDUCATION OF POOR GIRLS IN NORTH WEST ENGLAND c1780 to 1860: A STUDY OF WARRINGTON AND CHESTER by Joyce Valerie Ireland A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire September 2005 EDUCATION OF POOR GIRLS IN NORTH WEST ENGLAND cll8Oto 1860 A STUDY OF WARRINGTON AND CHESTER ABSTRACT This study is an attempt to discover what provision there was in North West England in the early nineteenth century for the education of poor girls, using a comparative study of two towns, Warrington and Chester. The existing literature reviewed is quite extensive on the education of the poor generally but there is little that refers specifically to girls. Some of it was useful as background and provided a national framework. In order to describe the context for the study a brief account of early provision for the poor is included. A number of the schools existing in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries continued into the nineteenth and occasionally even into the twentieth centuries and their records became the source material for this study. The eighteenth century and the early nineteenth century were marked by fluctuating fortunes in education, and there was a flurry of activity to revive the schools in both towns in the early nineteenth century. The local archives in the Chester/Cheshire Record Office contain minute books, account books and visitors' books for the Chester Blue Girls' school, Sunday and Working schools, the latter consolidated into one girls' school in 1816, all covering much of the nineteenth century. -

P1 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

P1 bus time schedule & line map P1 Frodsham - Priestley College View In Website Mode The P1 bus line (Frodsham - Priestley College) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Frodsham: 4:15 PM (2) Wilderspool: 7:46 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest P1 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next P1 bus arriving. Direction: Frodsham P1 bus Time Schedule 42 stops Frodsham Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 4:15 PM Greenalls Distillery, Wilderspool Tuesday 4:15 PM Loushers Lane, Wilderspool Wilderspool Causeway, Warrington Wednesday 3:30 PM Morrisons, Wilderspool Thursday 4:15 PM Friday 4:15 PM St Thomas' Church, Stockton Heath Saturday Not Operational Mullberry Tree Pub, Stockton Heath Methodist Church, Stockton Heath The Village Terrace, Warrington P1 bus Info Belvoir Road, Walton Direction: Frodsham Stops: 42 Walton Arms, Higher Walton Trip Duration: 54 min Line Summary: Greenalls Distillery, Wilderspool, Hobb Lane, Moore Loushers Lane, Wilderspool, Morrisons, Wilderspool, St Thomas' Church, Stockton Heath, Mullberry Tree Pub, Stockton Heath, Methodist Church, Stockton Ring O Bells, Daresbury Heath, Belvoir Road, Walton, Walton Arms, Higher Walton, Hobb Lane, Moore, Ring O Bells, Daresbury, D D Park Hotel, Daresbury Delph Park Hotel, Daresbury Delph, Chester Road, Preston on the Hill, Post O∆ce, Preston Brook, Chester Road, Chester Road, Preston on the Hill Preston Brook, Travel Inn, Preston Brook, Chester Road, Murdishaw, Post O∆ce, Sutton Weaver, Aston Post O∆ce, Preston -

THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION for ENGLAND ELECTORAL REVIEW of CHESHIRE WEST and CHESTER Draft Recommendations For

SHEET 1, MAP 1 THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND ELECTORAL REVIEW OF CHESHIRE WEST AND CHESTER Draft recommendations for ward boundaries in the borough of Cheshire West and Chester August 2017 Sheet 1 of 1 ANTROBUS CP This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office © Crown copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. The Local Government Boundary Commission for England GD100049926 2017. WHITLEY CP SUTTON WEAVER CP Boundary alignment and names shown on the mapping background may not be up to date. They may differ from the latest boundary information NETHERPOOL applied as part of this review. DUTTON MARBURY ASTON CP GREAT WILLASTON WESTMINSTER CP FRODSHAM BUDWORTH CP & THORNTON COMBERBACH NESTON CP CP INCE LITTLE CP LEIGH CP MARSTON LEDSHAM GREAT OVERPOOL NESTON & SUTTON CP & MANOR & GRANGE HELSBY ANDERTON PARKGATE WITH WINCHAM MARBURY CP WOLVERHAM HELSBY ACTON CP ELTON CP S BRIDGE CP T WHITBY KINGSLEY LOSTOCK R CP BARNTON & A GROVES LEDSHAM CP GRALAM CP S W LITTLE CP U CP B T E STANNEY CP T O R R N Y CROWTON WHITBY NORTHWICH CP G NORTHWICH HEATH WINNINGTON THORNTON-LE-MOORS D WITTON U ALVANLEY WEAVERHAM STOAK CP A N NORTHWICH NETHER N H CP CP F CAPENHURST CP D A WEAVER & CP PEOVER CP H M CP - CUDDINGTON A O D PUDDINGTON P N S C RUDHEATH - CP F T O H R E NORLEY RUDHEATH LACH CROUGHTON D - H NORTHWICH B CP CP DENNIS CP SAUGHALL & L CP ELTON & C I MANLEY -

Raven Newsletter

TheNo.17 Winter 2011 aven RThe quarterly magazine for the whole of Rainow G Village News G Social Events G Parish Council News G Clubs & Societies G School & Church The Parish Council would like to wish everyone a very.... Happy and Peaceful Christmas and New Year Very BestWishes for 2012 Winter Gritting Signage We have asked that the bins already in place at We are endeavouring to get Highways to improve the Rainow Primary School, Chapel Lane near Millers signage for Bull Hill and hopefully prevent HGVs from Meadow, the stone bin on Lidgetts Lane, Millers using the road. Meadow (near Spinney), Sugar Lane at the junction Community Pride Competition Hough Close and on Berristall Lane be kept filled. Rainow has received the “Little Gem” award in this Highways are also depositing 1/2 tonne sacks of salt year’s competition for Trinity Gardens and Highly mix at strategic locations in the parish to assist when Commended for the Raven newsletter. the weather is particularly wintery. They will be dropped on the verge as they are and the salt can be spread Civic Service from the sack. We have asked for sacks at the top of The Civic Service was once again a great success Sugar Lane, top of Round Meadow near telephone with Steve Rathbone providing, as ever, a splendid kiosk, Berristall Lane (should the bin not be filled), service. Over Alderley Brass Band accompanied the Tower Hill and mid-point of Kiskill Lane. In addition, choir and congregation with the hymns. Amongst the Tom Briggs will continue to salt Round Meadow, Millers guests were the Mayor of Cheshire East Roger West, Meadow and Sugar Lane. -

The Archaeology of Mining, and Quarrying, for Salt and the Evaporites (Gypsum, Anhydrite, Potash and Celestine)

The archaeology of mining, and quarrying, for Salt and the Evaporites (Gypsum, Anhydrite, Potash and Celestine) Test drafted by Peter Claughton Rock salt, or halite (NaCl- sodium chloride), has been mined since the late 17th century, having been discovered during exploratory shaft sinking for coal at Marbury near Northwich, Cheshire, in November 1670. Prior to that the brine springs of Cheshire and those at Droitwich in Worcestershire were the source of salt produced by evaporation, along with production from a large number of coastal sites using seawater. Alabaster, fine grained gypsum (CaSO4. 2H2O - hydrated calcium sulphate), has however been quarried in the East Midlands for use in sculpture since at least the 14th century (Cheetham 1984, 11-13) and the use of gypsum for making plaster dates from about the same period. Consumption The expansion of mining and quarrying for salt and the other evaporites came in the 19th century with the development of the chemical industry. Salt (sodium chloride) was a feedstock for the production of the chlorine used in many chemical processes and in the production of caustic soda (sodium hydroxide) and soda ash (sodium carbonate). Anhydrite (anhydrous calcium sulphate) was used in the production of sulphuric acid. Salt or halite (rock salt) was first mined at Winsford in Cheshire (the site of the only remaining active rock salt mine in England) in 1844. Production expanded in the late 19th century to feed the chemical industry in north Cheshire (together with increasing brine production from the Northwich salt fields). The Lancashire salt deposits, on the Wyre estuary at Fleetwood and Preesall, not discovered until 1872 whilst boring in search of haematite (Landless 1979, 38), were a key to the development of the chemical industry in that area. -

William Furmval, H. E. Falk and the Salt Chamber of Commerce, 1815-1889: "Ome Chapters in the Economic History of Cheshire

WILLIAM FURMVAL, H. E. FALK AND THE SALT CHAMBER OF COMMERCE, 1815-1889: "OME CHAPTERS IN THE ECONOMIC HISTORY OF CHESHIRE BY W. H. CHALONER, M.A., PH.D. Read 17 November 1960 N the second volume of his Economic History of Modern I Britain (p. 145), Sir John Clapham, writing of the chambers of commerce and trade associations which multiplied rapidly after 1860, suggested that between 1850 and 1875 "there was rather less co-operation among 'capitalist' producers than there had been in the more difficult first and second quarters" of the nineteenth century. He mentioned that in the British salt industry there had been price-fixing associations "based on a local monopoly" in the early nineteenth century, and added that after 1825 the industry "witnessed alternations of gentle men's agreements and 'fighting trade' " until the formation of the Salt Union in 1888. This combine has been called "the first British trust", but to the salt proprietors of the time it was merely "a new device, made easier by limited liability, for handling an old problem". (1) The purpose of this study is to examine in greater detail the business organisation of the natural local monopoly enjoyed by the Cheshire saltmakers in the nineteenth century and to trace the part played by "The Coalition" and the Salt Chamber of Commerce in fostering price regulation and output restriction between the end of the Napoleonic Wars and 1889.< 2 > 111 Op. cit., pp. 147-8; see also Accounts and Papers, 1817, III, 123, p. 22, and E. Hughes, Studies in Administration and Finance, 1558-1825 (1934), pp. -

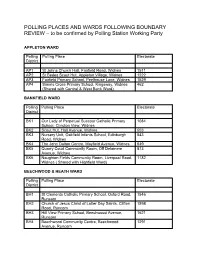

POLLING PLACES and WARDS FOLLOWING BOUNDARY REVIEW – to Be Confirmed by Polling Station Working Party

POLLING PLACES AND WARDS FOLLOWING BOUNDARY REVIEW – to be confirmed by Polling Station Working Party APPLETON WARD Polling Polling Place Electorate District AP1 St Johns Church Hall, Fairfield Road, Widnes 1511 AP2 St Bedes Scout Hut, Appleton Village, Widnes 1222 AP3 Fairfield Primary School, Peelhouse Lane, Widnes 1529 AP4 Simms Cross Primary School, Kingsway, Widnes 462 (Shared with Central & West Bank Ward) BANKFIELD WARD Polling Polling Place Electorate District BK1 Our Lady of Perpetual Succour Catholic Primary 1084 School, Clincton View, Widnes BK2 Scout Hut, Hall Avenue, Widnes 553 BK3 Nursery Unit, Oakfield Infants School, Edinburgh 843 Road, Widnes BK4 The John Dalton Centre, Mayfield Avenue, Widnes 649 BK5 Quarry Court Community Room, Off Delamere 873 Avenue, Widnes BK6 Naughton Fields Community Room, Liverpool Road, 1182 Widnes ( Shared with Highfield Ward) BEECHWOOD & HEATH WARD Polling Polling Place Electorate District BH1 St Clements Catholic Primary School, Oxford Road, 1546 Runcorn BH2 Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, Clifton 1598 Road, Runcorn BH3 Hill View Primary School, Beechwood Avenue, 1621 Runcorn BH4 Beechwood Community Centre, Beechwood 1291 Avenue, Runcorn BIRCHFIELD WARD Polling Polling Place Electorate District BF1 Halton Farnworth Hornets, ARLFC, Wilmere Lane, 1073 Widnes BF2 Marquee Upton Tavern, Upton Lane, Widnes 3291 BF3 Mobile Polling Station, Queensbury Way, Widnes – 1659 **To be re-sited further up Queensbury Way BRIDGEWATER WARD Polling Polling Place Electorate District BW1 Brook Chapel, -

Cheshire East: Developing Emotionally Healthy Children and Young People

CHESHIRE EAST: DEVELOPING EMOTIONALLY HEALTHY CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE The Cheshire East emotionally healthy children and young people partnership is led by Cheshire East council’s children’s services, and is primarily funded from the council’s public health budget. Many organisations have been actively involved in developing the partnership including the NHS’s local clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) and children’s and adolescents mental health services (CAMHS), headteachers, and several vol- untary organisations. As a council senior manager explained: “It’s all partnership working. We work with schools, with the CCG, with health providers, with school nurses, health visitors, early years services, third sector organisations.” As a health lead commented: “It is pretty unique in its nature and scope.” The partnership’s aim is to support children and young people in becoming more mentally resilient: to be better able to manage their own mental health, to pro- cess what is going on in their environment, and to access specialist services should they need them. They want to reduce the number of children and young people attending accident and emergency services, or being inappropriately re- ferred to the CAMHS. The partnership’s original focus was creating ‘emotionally healthy schools’, but they are now extending their reach into early years settings. “We have been really blessed in support from above. We have had investment in to this project year after year. The moral and ethical support is there but also Pinancial.” INITIAL PHASE In 2015 CCGs were required to produce a local ‘children and mental health trans- formation plan’ to implement the NHS’s national ‘Five Year Forward View’ and ‘Future in Mind’ recommendations. -

Strategy 2021-2025 Introduction Our Vision

Improving Health and Wellbeing in Cheshire and Merseyside Strategy 2021-2025 Introduction Our Vision The NHS Long Term Plan published in 2019 called for health and care to be more joined up locally to meet people’s needs. Since then, ICSs (Integrated Care Systems) We want everyone in Cheshire and Merseyside to have developed across England as a vehicle for the NHS to work in partnership have a great start in life, and get the support they with local councils and other key stakeholders to take collective responsibility for need to stay healthy and live longer. improving the health and wellbeing of the population, co-ordinating services together and managing resources collectively. Cheshire and Merseyside was designated an ICS by NHS England in April 2021. Our Mission Cheshire and Merseyside is one of the largest ICSs with a population of 2.6 million people living across a large and diverse geographical footprint. We will tackle health inequalities and improve the The ICS brings together nine ‘Places’ lives of the poorest fastest. We believe we can do coterminous with individual local this best by working in partnership. authority boundaries, 19 NHS Provider Trusts and 51 Primary Care Networks. There are many underlying population In the pages that follow, we set out our strategic objectives and associated aspirations health challenges in the region; for that will enable us to achieve our vision and mission over the next five years. They are example in Liverpool City Region 44% derived from NHS England’s stated purpose for ICSs and joint working with our partners of the population live in the top 20% to identify the key areas for focus if we are to reduce health inequalities and improve lives. -

Methodist Memorial A5 V2.Qxp:Methodist Memorial A5.Q5 6 12 2008 00:56 Page 1

Methodist Memorial A5 v2.qxp:Methodist Memorial A5.Q5 6 12 2008 00:56 Page 1 METHODIST MEMORIAL by Charles Atmore Methodist Memorial A5 v2.qxp:Methodist Memorial A5.Q5 6 12 2008 00:56 Page 3 METHODIST MEMORIAL BY CHARLES ATMORE QUINTA PRESS Weston Rhyn 2008 Methodist Memorial A5 v2.qxp:Methodist Memorial A5.Q5 6 12 2008 00:56 Page 4 Quinta Press Meadow View, Weston Rhyn, Oswestry, Shropshire, England, SY10 7RN Methodist Memorial first published in 1871 by Hamilton, Adams & Co. The layout of this edition © Quinta Press 2008 Set in 10pt on 12 pt Bembo Std ISBN 1 897856 xx x Methodist Memorial A5 v2.qxp:Methodist Memorial A5.Q5 6 12 2008 00:56 Page 5 THE METHODIST MEMORIAL BEING AN IMPARTIAL SKETCH OF THE LIVES AND CHARACTERS OF THE PREACHERS WHO HAVE DEPARTED THIS LIFE SINCE THE COMMENCEMENT OF THE WORK OF GOD AMONG THE PEOPLE CALLED METHODISTS LATE IN CONNECTION WITH THE REV. JOHN WESLEY, DECEASED. Drawn from the most authentic Sources, and disposed in Alphabetical Order. Introduced with a brief Account of the STATE OF RELIGION FROM THE EARLIEST AGES, AND A CONCISE HISTORY OF METHODISM. By CHARLES ATMORE. WITH AN ORIGINAL MEMOIR OF THE AUTHOR, And Notices of some of his Contemporaries. Whose faith follow, considering the end of their conversation, Jesus Christ, the same yesterday, and today, and for ever. ST PAUL. According to this time, it shall be said of Jacob and of Israel, What hath God wrought? MOSES. 5 Methodist Memorial A5 v2.qxp:Methodist Memorial A5.Q5 6 12 2008 00:56 Page 6 LONDON: HAMILTON, ADAMS, & CO., 32, PATERNOSTER ROW.