Examples of Harappan Burial Practices and Customs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yoga of Inner Sound)

Blessings Om Sadgurave Namah! Meditation on Bindu & Nada occupies the highest pedestal in Santmat, for this meditation is the only means to scale the dizziest of heights that a spiritual seeker can ever aspire for. Several editions of my book “Bindu Nada Dhyan” have been published. Some Satsang lovers translated and got the book published in Bengali also. Very recently it has also been translated into Marathi language. Now Prof. Pravesh Kumar Singh has translated it into English. I thank him heartily for the noble task and pray to my most adorable Guru Maharaj for his progress. Jai Guru! Achyutanand Ram Navami 12th April 2011 Yoga of Inner Light & Sound Author Swami Achyutanand Translator Pravesh Kumar Singh Santmat Satsang Samiti, Chandrapur © All Rights Reserved, The Translator Publisher: Santmat Satsang Samiti, Chandrapur Related Link: http://groups.yahoo.com/group/sant_santati Price: ` 5. $ 5 (US) Printers: Kailash Printers, Aurangabad Maharashtra, India The Secret Pathway to God's Abode... - A Poem by Maharshi Mehi Paramhans Ji Maharaj A scintillating point-light is sighted in the Sushumna (the centre of the Ajnā Chakra) | Behold (this point), O brother, with the curtains of your eyelids down ||1|| (The spiritual practitioner) who stills his sight in the Third Til (Sushumna, or the centre or the Ajnā Chakra), | Moves beyond his body and enters into the macrocosm. ||2|| The inner sky, studded with sparkling stars, is laid open (to such a practitioner). | Light resembling that of the earthen lamp-flame (that is seen within) dispels the darkness (of the inner sky). ||3|| The inner horizon is illumined with incomparable moonlight. -

Harappan Geometry and Symmetry: a Study of Geometrical Patterns on Indus Objects

Indian Journal of History of Science, 45.3 (2010) 343-368 HARAPPAN GEOMETRY AND SYMMETRY: A STUDY OF GEOMETRICAL PATTERNS ON INDUS OBJECTS M N VAHIA AND NISHA YADAV (Received 29 October 2007; revised 25 June 2009) The geometrical patterns on various Indus objects catalogued by Joshi and Parpola (1987) and Shah and Parpola (1991) (CISI Volumes 1 and 2) are studied. These are generally found on small seals often having a boss at the back or two button-like holes at the centre. Most often these objects are rectangular or circular in shape, but objects of other shapes are also included in the present study. An overview of the various kinds of geometrical patterns seen on these objects have been given and then a detailed analysis of few patterns which stand out of the general lot in terms of the complexity involved in manufacturing them have been provided. It is suggested that some of these creations are not random scribbles but involve a certain understanding of geometry consistent with other aspects of the Indus culture itself. These objects often have preferred symmetries in their patterns. It is interesting to note that though the swastika symbol and its variants are often used on these objects, other script signs are conspicuous by their absence on the objects having geometric patterns. Key words: CISI volumes, Geometric pattern, Grid design, Swastika 1. INTRODUCTION Towns in the Indus valley have generally been recognised for their exquisite planning with orthogonal layout. This has been used to appreciate their understanding of geometry of rectangles and related shapes. -

1.2 Origin of the Indus Valley Civilization

8 MM VENKATESHWARA ASPECTS OF ANCIENT INDIAN OPEN UNIVERSITY ART AND ARCHITECTURE www.vou.ac.in ASPECTS OF ANCIENT INDIAN ART AND ARCHITECTURE AND ART INDIAN ANCIENT OF ASPECTS ASPECTS OF ANCIENT INDIAN ART AND ARCHITECTURE [M.A. HISTORY] VENKATESHWARA OPEN UNIVERSITYwww.vou.ac.in ASPECTS OF ANCIENT INDIAN ART AND ARCHITECTURE MA History BOARD OF STUDIES Prof Lalit Kumar Sagar Vice Chancellor Dr. S. Raman Iyer Director Directorate of Distance Education SUBJECT EXPERT Dr. Pratyusha Dasgupta Assistant Professor Dr. Meenu Sharma Assistant Professor Sameer Assistant Professor CO-ORDINATOR Mr. Tauha Khan Registrar Author: Dr. Vedbrat Tiwari, Assistant Professor, Department of History, College of Vocational Studies, University of Delhi Copyright © Author, 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this publication which is material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or transmitted or utilized or stored in any form or by any means now known or hereinafter invented, electronic, digital or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the Publisher. Information contained in this book has been published by VIKAS® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. and has been obtained by its Authors from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. However, the Publisher and its Authors shall in no event be liable for any errors, omissions or damages arising out of use of this information and specifically disclaim any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular use. Vikas® is the registered trademark of Vikas® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. VIKAS® PUBLISHING HOUSE PVT LTD E-28, Sector-8, Noida - 201301 (UP) Phone: 0120-4078900 Fax: 0120-4078999 Regd. -

Tracing the Tradition of Sartorial Art in Indo-Pak Sub-Continen

TRACING THE TRADITION OF SARTORIAL ART IN INDO-PAK SUB-CONTINEN ZUBAIDA YOUSAF Abstract The study of clothing in Pakistan as a cultural aspect of Archaeological findings was given the least attention in the previous decades. The present research is a preliminary work on tracing the tradition of sartorial art in the Indo-Pak Sub-Continent. Once the concept of the use of untailored and minimal drape, and unfamiliarity with the art of tailoring in the ancient Indus and Pre Indus societies firmly established on the bases of early evidences, no further investigation was undertaken to trace the history of tailored clothing in remote antiquity. Generally, the history of tailored clothing in Indo-Pak Sub-Continent is taken to have been with the arrival of Central Asian nations such as Scythians, Parthians and Kushans from 2nd century BC and onward. But the present work stretches this history back to the time of pre-Indus cultures and to the Indus Valley Civilization. Besides Mehrgarh, Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa, many newly exposed proto historic sites such as Mehi, Kulli, Nausharo, Kalibangan, Dholavira, Bhirrana, Banawali etc. have yielded a good corpus of researchable material, but unfortunately this data wasn’t exploited to throw light on the historical background of tailored clothing in the Indo-Pak Sub-Continent. Though we have scanty evidences from the Indus and Pre-Indus sites, but these are sufficient to reopen the discussion on the said topic. Keywords: Indus, Mehrgarh, Dholavira, Kulli, Mehi, Kalibangan, Harappa, Mohenjao- Daro, Clothing, Tailoring. 1 Introduction The traced history of clothing in India and Pakistan goes back to the 7th millennium BC. -

Bi-Annual Research Journal “BALOCHISTAN REVIEW—ISSN

- i - ISSN: 1810—2174 Balochistan Review Volume XXVIII No. 1, 2013 (HEC RECOGNIZED) Editor: Ghulam Farooq Baloch BALOCHISTAN STUDY CENTRE UNIVERSITY OF BALOCHISTAN, QUETTA-PAKISTAN - ii - Published bi-annually by the Balochistan Study Centre, University of Balochistan, Quetta-Pakistan. @ Balochistan Study Centre 2013-1 Subscription rate (per annum) in Pakistan: Institutions: Rs. 300/- Individuals: Rs. 200/- For the other countries: Institutions: US$ 50 Individuals: US$ 30 Contact: Balochistan Review—ISSN: 1810-2174 Balochistan Study Centre, University of Balochistan, Quetta-Pakistan. Tel: (92) (081) 9211255 Facsimile: (92) (081) 9211255 E-mail: [email protected] Website: uob.edu.pk - iii - Editorial Board Patron in Chief: Prof. Dr. Rasul Bakhsh Raisani Vice Chancellor, University of Balochistan, Quetta-Pakistan. Patron Prof. Dr. Abdul Hameed Shahwani Director, Balochistan Study Centre, UoB, Quetta-Pakistan. Editor Ghulam Farooq Baloch Asstt Professor Balochistan Study Centre, UoB, Quetta-Pakistan. Assistant Editor Waheed Razzaq Research Officer Balochistan Study Centre, UoB, Quetta-Pakistan. Members: Prof. Dr. Andriano V. Rossi Vice Chancellor & Head Dept of Asian Studies, Institute of Oriental Studies, Naples, Italy. Prof. Dr. Saad Abudeyha Chairman, Dept. of Political Science, University of Jordon, Amman, Jordon. Prof. Dr. Bertrand Bellon Professor of Int’l, Industrial Organization & Technology Policy, University de Paris Sud, France. Dr. Carina Jahani Inst. of Iranian & African Studies, Uppsala University, Sweden. Prof. Dr. Muhammad Ashraf Khan Director, Taxila Institute of Civilization, Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, Pakistan. Prof. Dr. Rajwali Shah Khattak Professor, Pushto Academy, University of Peshawar, Pakistan. Mr. Ayub Baloch Member, Balochistan Public Service Commission, Quetta. Prof. Dr. Mehmood Ali Shah, Professor Emeritus, University of Balochistan, Quetta. -

Ornament Styles of the Indus Valley Tradition: Evidence from Recent Excavations at Harappa, Pakistan

PALEORIENT, vol. 17/2 - 1991 ORNAMENT STYLES OF THE INDUS VALLEY TRADITION: EVIDENCE FROM RECENT EXCAVATIONS AT HARAPPA, PAKISTAN J.M. KENOYER ABSTRACT. - Recent excavations at Harappa and Mehrgarh, as well as other sites in Pakistan and India have provided new opportunities to study the ornaments of the Indus Civilization. A brief discussion of the methodologies needed for the study of Indus ornaments is presented along with examples of how Indus artisans combined precious metals, stone beads, shell and faience to form elaborate ornaments. Many of these ornament styles were also copied in more easily obtained materials such as steatite or terra-cotta. The social and ritual implications of specific ornaments are' examined through their archaeological context and ... comparisons with the function of specific ornaments are recorded in the ancient texts and folk traditions of South Asia. RESUME. - Les fouilles recentes effectuees a Harappa, a Mehrgarh, et sur d'autres sites au Pakistan et en Inde offrent des possibilites nouvelles pour l'etude des parures de la Civilisation de I'Indus. Les methodes utilisees pour l'etude des parures de la tradition Indus sont presentees et commentees rapidement, ainsi que Ie sont quelques exemples de parures specijiques, produit elabore du travail des artisans de l'Indus qui allient les materiaux precieux, la pierre, les coquillages et la fai'ence. On copiait aussi ces parures dans des materiaux d'obtention plus facile tels que la steatite ou la terre cuite. Grtice au contexte archeologique, mais aussi a des comparaisons avec la fonction de parures specijiques decrites dans les textes anciens et les traditions populaires de l'Asie du sud, sont erudiees aussi les implications sociales et rituelles de parures specijiques. -

Late Shri Janaki Mandal Ji, the Grandfather of Revered Swami

Late Shri Janaki Mandal ji, the grandfather of Revered Swami Bhagirath Baba, was a resident of Lalganj, a village under Rupauli Police Station of Purnia District in the state of Bihar, India. He was an intensely devout person, and used to organise every year a series of discourses on Bhagwat (a scripture illustrating the exploits of all the incarnations of Lord Vishnu, especially that of His incarnation as Lord Shri Krishna) for a fortnight spanning from Amavasya (New Moon Day) to Poornima (Full Moon Day) of the Hindu month of Vaishakh (coinciding with the month of May usually). It was during one such occasion that Swami Bhagirath Das ji was born - on Tuesday the 09th May of 1945, the 11th day of the light half of the month of Vaishakh - while the discourse on the Bhagvat was going on. It is for this reason that Late Shri Janki Mandal ji gave the name ‘Bhagvat Mandal‘ to him. His venerable mother, Late Mrs. Dhanasi Devi, took ill immediately after his birth and, thus, the onus of his upbringing fell upon his grandmother and aunt (father’s sister). So, Bhagirath Baba got very little opportunity of receiving his mother’s milk. Swami Bhagirath Das ji was very quiet or calm by nature. He loved sitting quietly in solitude. His family members would get amazed by his temperament. Even in his childhood days he displayed a natural attraction for sages; seeing hermits or sages he would run to them and pay his obeisance. He did not have much inclination towards studies; he preferred rather to sit alone with his eyes closed. -

Unit 5 Antecedents, Chronology and Geographical Spread

UNIT 5 ANTECEDENTS, CHRONOLOGY . AND GEOGRAPHICAL SPREAD 5.1 Introduction 5.2 An Old City is Discovered 5.3 The Age of the Harappan Civilization 5.4 Why it is called the Harappan Civilization 5.5 Antecedents 5.6 Geographical Features 5.7 Origins of Agriculture and Settled Villages 5.8 The Early Harappan Period 5.8.1 Southern Afghanistan 5.8.2 Quetta Valley 5.8.3 Central and Southern Baluchistan 1 5.8.4 The Indus Area 5.8.5 Punjab and Bahawalpur 5.8.6 Kalibangan 5.11 Key Words 5.12 Answers to Check Your Progress 'Ekercises 5.0 OBJECTIVES I After reading this unit, you will be able to learn: how the Harappan Civilization was discovered, how its chronology was determined, how the village communities gradually evolved into the Harappan Civilization, and the geographical spread of the Harappan Civilization. 5.1 INTRODUCTION In Block 1 you learnt about the evolutiqn of mankind from hunting gathering societies to agricultural societies. The invention of agriculture led to far reaching changes in human societies. One important result was the emergence of cities and civilizations. In this Unit you will be made familiar with the birth of one such civilization namely the Harappan civilization. 5.2 AN OLD CITY IS DISCOVERED In 1826 an English man Charles Masson visited a village named Harappa in Western Punjab (now in Pakistan). He noted the remarkably high walls, and towers of a very old settlement. He believed that this city belonged to the times of Alexander the Great. In 1872, a famous archaeologist Sir Alexander Cunningham came to this place. -

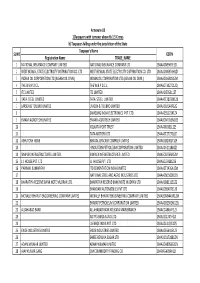

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

Annexure-1B 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores b) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the State Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LIMITED NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LTD 19AAACN9967E1Z0 2 WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD 19AAACW6953H1ZX 3 INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) 19AAACI1681G1ZM 4 THE W.B.P.D.C.L. THE W.B.P.D.C.L. 19AABCT3027C1ZQ 5 ITC LIMITED ITC LIMITED 19AAACI5950L1Z7 6 TATA STEEL LIMITED TATA STEEL LIMITED 19AAACT2803M1Z8 7 LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED 19AAACL0140P1ZG 8 SAMSUNG INDIA ELECTRONICS PVT. LTD. 19AAACS5123K1ZA 9 EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED 19AABCN7953M1ZS 10 KOLKATA PORT TRUST 19AAAJK0361L1Z3 11 TATA MOTORS LTD 19AAACT2727Q1ZT 12 ASHUTOSH BOSE BENGAL CRACKER COMPLEX LIMITED 19AAGCB2001F1Z9 13 HINDUSTAN PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED. 19AAACH1118B1Z9 14 SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. 19AAECS0765R1ZM 15 J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD 19AABCJ5928J2Z6 16 PARIMAL KUMAR RAY ITD CEMENTATION INDIA LIMITED 19AAACT1426A1ZW 17 NATIONAL STEEL AND AGRO INDUSTRIES LTD 19AAACN1500B1Z9 18 BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. 19AAACB8111E1Z2 19 BHANDARI AUTOMOBILES PVT LTD 19AABCB5407E1Z0 20 MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED 19AABCM9443R1ZM 21 BHARAT PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED 19AAACB2902M1ZQ 22 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLAHABAD BANK KOLKATA MAIN BRANCH 19AACCA8464F1ZJ 23 ADITYA BIRLA NUVO LTD. 19AAACI1747H1ZL 24 LAFARGE INDIA PVT. LTD. 19AAACL4159L1Z5 25 EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACE6641E1ZS 26 SHREE RENUKA SUGAR LTD. 19AADCS1728B1ZN 27 ADANI WILMAR LIMITED ADANI WILMAR LIMITED 19AABCA8056G1ZM 28 AJAY KUMAR GARG OM COMMODITY TRADING CO. -

World Bank Document

MINISTRY OF ROAD TRANSPORT & HIGHWAY GOVERNMENT OF INDIA Public Disclosure Authorized CONSULTANCY SERVICES FOR DETAILED PROJECT REPORT FOR REHABILITATION AND UPGRADING TO 2 LANE/2 LANE WITH PAVED SHOULDER OF BIRPUR TO BIHPUR SECTION OF NH-106 (KM 0. 000 TO KM 136.00) (BIHAR) Package I SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT& RAP REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized February – 2014 Public Disclosure Authorized Up gradation of Birpur- Bihpur Section of NH 106 in the State of Bihar Social Impact Assessment & RAP Social Impact Assessment & RAP Report (FINAL) TABLE OF CONTENTS S. Description Page No ABBREVIATIONS Executive Summary ES 1-7 1. PROJECT BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION 1-1 to 1-4 1.1 Project Background 1-1 1.2 Project Description 1-1 1.3 Approach and Methodology 1-3 2. SOCIO-ECONOMIC PROFILE OF THE PROJECT INFLUENCE ZONE 2-1 to 2-5 2.1 Introduction 2-1 2.2 Socio- Economic Status of Project influence District 2-1 2.2.1 Supaul District 2-1 2.2.2 Madhepura District 2-1 2.2.3 Saharsa District 2-2 2.3 Direct Impact Zone 2-2 2.4 Socio-Economic Profiling 2-3 2.5 Existing Public Amenities 2-4 2.5.1 Educational Service 2-4 2.5.2 Health CARE Service 2-4 2.5.3 Market Facility 2-4 2.5.4 Transport Facilities 2-4 3. ANALYSIS OF ALTERNATIVES & PROPOSED IMPROVEMENT 3-1 to 3-3 PLAN 3.1 Introduction 3-1 3.2 Design Considerations 3-1 3.3 Considerations of Alternatives 3-2 3.3.1 Proposed Realignments 3-2 Client : MoRT&H Up gradation of Birpur- Bihpur Section of NH 106 in the State of Bihar Social Impact Assessment & RAP 4. -

Divine Light and Melodies Lead the Way: the Santmat Tradition of Bihar

religions Article Divine Light and Melodies Lead the Way: The Santmat Tradition of Bihar Veena R. Howard Department of Philosophy, California State University, Fresno, CA 93740, USA; [email protected] Received: 22 February 2019; Accepted: 20 March 2019; Published: 27 March 2019 Abstract: This paper focuses on the branch of Santmat (thus far, unstudied by scholars of Indian religions), prevalent in the rural areas of Bihar, India. Santmat—literally meaning “the Path of Sants” or “Point of View of the Sants”—of Bihar represents a unique synthesis of the elements of the Vedic traditions, rural Hindu practices, and esoteric experiences, as recorded in the poetry of the medieval Sant Tradition. I characterize this tradition as “Santmat of Bihar” to differentiate it from the other branches of Santmat. The tradition has spread to all parts of India, but its highest concentration remains in Bihar. Maharishi Mehi, a twentieth-century Sant from Bihar State, identifies Santmat’s goal as ´santi¯ . Maharishi Mehi defines S´anti¯ as the state of deep stillness, equilibrium, and the unity with the Divine. He considers those individuals sants who are established in this state. The state of sublime peace is equally available to all human beings, irrespective of gender, religion, ethnicity, or status. However, it requires a systematic path. Drawing on the writings of the texts of Sanatana¯ Dharma, teachings of the Sants and personal experiences, Maharishi Mehi lays out a systematic path that encompasses the moral observances and detailed esoteric experiences. He also provides an in-depth description of the esoteric practices of divine light (dr.s.ti yoga) and sound (surat ´sabdayoga) in the inner meditation. -

Mission Archéologique De L'indus (M.A.I.)

Mission archéologique de l’Indus (M.A.I.) Création de la Mission archéologique française de l’Indus La MAI a démarré ses activités à l’aube de la partition Inde-Pakistan, en 1947[1] sous la direction de Jean-Marie et Casal[2] à Pondichéry[3] sous l’appellation Mission des Indes qu’elle gardera jusqu’aux fouilles de Mundigak, en Afghanistan, dans les années 1950[4]. Depuis 1975, et jusqu’en 2012 elle à été dirigée par Jean-François Jarrige, directeur de recherche émérite au CNRS et membre de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. Des 2013, le programme de la Mission Archéologique Française au Makran et de la Mission de l’Indus seront fusionnées pour former la Mission Archéologique du Bassin de l’Indus, sous la responsabilité d’Aurore Didier. La Mission archéologique de l’Indus au Pakistan Les activités de la M.A.I. ont débuté dans la région du Sindh (Pakistan) par la fouille du site d’Amri en 1958 par Jean-Marie Casal, conservateur au Musée Guimet et détaché au CNRS, dans un pays qui était traditionnellement le domaine réservé des anglo-saxons. A partir de 1962, les travaux se sont poursuivis dans la province du Balochistan. Les fouilles de Nindowari de 1962 à 1965, dans une vallée montagneuse du Balochistan méridional, ont permis de dégager les vestiges d’une agglomération de plus de 25 hectares appartenant, pour ses deuxième et troisième phases d’occupation, à la culture de Kulli, datée du 3ème millénaire avant notre ère. En 1967, la mission archéologique a concentré ses activités dans le nord de la plaine de Kachi et le bassin de la Bolan qui se trouvent au débouché du col de Bolan, une des principales voies de communication entre l’Afghanistan méridional, l’Iran de l’Est, les reliefs du Balochistan et la vallée de l’Indus.