Point No Point History Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Native Plant Garden

The Mountaineers: Seattle Branch Naturalists Newsletter March 2019 Naturalists ONE STEP AT A TIME Contents • In the Native Plant Garden .......1 In the Native Plant Garden • February Hikes .............................2 The native plant garden is now enjoying much needed care and rejuvenation thanks to the Washington Native Plant Society local chapter, who are providing • Upcoming Hikes ...........................5 leadership in the garden in terms of care, planting and a vision of the garden. With leadership from George Macomber. The garden is benefitting from their • Lecture Series ..............................5 experience in native plant care and propagation. • Native Plant Society ...................6 The Native Plant Society is having work parties and we will be invited to • Odds and Ends .............................7 participate. Their hand is already showing in the careful pruning, cleaning and clearing and many of our plantings will benefit. Check out the garden. It is just • Photos ............................................11 by the climbing rocks on the north end of the Seattle clubhouse. • Intro to Natural World ...............12 • Contact Info .................................13 JOIN US ON: Facebook Flickr Red flowering current Pruning work at the garden 1 The Mountaineers: Seattle Branch Naturalists Newsletter February Naturalist Hikes MOSS WORKSHOP FIELD TRIP – REDMOND WATER PRESERVE Mossbacks OLD SAUK RIVER TRAIL – FEB 2 As we discovered this is arguably the best moss laden trail we’ve ever been on. It was covered with -

National Register of Historic Places

Form No. 10-306 (Rev. 10-741 UNITtDSTATtSDhPARTMENTOHTHt INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLAGES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS __________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ I NAME HISTORIC LIGHT STATION AND/OR COMMON Q LOCATION STREET & NUMBER U> f\ T 3 3* _NOTFOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT MLJKTLTEO — VICINITY OF 2nd STATE v. CODE COUNTY CODE W2\SHTJ^5TON 53 SNOHOMISH 061 CLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT X-PUBLIC —iSXXUPIED _AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM jegUILDING(S) _PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH _WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS _OBJECT _IN PROCESS XXTES: RESTRICTED X.GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL XXTRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: AGENCY U.S. COAST GUARD REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: THIRTEENTH COAST GUARD DISTRICT (flp) STREET & NUMBER 915 Second Avenue CITY. TOWN STATE Seattle VICINITY OF Washington 98174 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC Snohomish County Recorder STREET & NUMBER Courthouse CITY, TOWN STATE Washington REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE NOME KNOWN DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY __LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED jg<LINALTERED JOjORIGINAL SITE X-GOOD _RUINS —ALTERED —MOVED DATE_______ —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The structure consists of a tower and connected engine house, both of which are frame construction. The tower base is square, twenty feet on a side, and rises one story to a decorative parallel band. Above this band, triangular squinches effect a transition to an octagonal plan. -

Wood Warblers of North America Kitsap Great Give Www

APRIL 2019 Kitsap Audubon Society – Since 1972 KingfisherTHE April 11, 2019, 7:00 to 9:00 p.m. - Poulsbo Library Wood Warblers of North America Photographer Robert Howson Our presenter, will focus on wood warblers from his Robert Howson, photographic collection of more than developed an early 500 North American, tropical and interest in birds while European bird species. still in grade school. The wood-warblers of North This interest continued America present a challenge to the throughout high school birders across our country. Even and into college where though they are a colorful group, he graduated with a identification can be a challenge. Not triple major in biology, only do certain members of the group history, and religion. make themselves difficult to see as He earned a Masters in they flit among the highest branches of history and worked on our tallest trees, but especially in fall, a Doctorate in religious their plumages can be confusing. They education. He has make up one of our largest families, taught on various levels, outnumbering plovers and sandpipers including elementary, combined. The same is true if you secondary, and college combine gulls and terns into a single ranks. Most recently he unit. Warbler species even outnumber was the chairman of the the total number of sparrow species history department at Townsend’s Warbler by found on our continent. We invite you Cedar Park Christian School in Bothell, Robert Howson. to attend a photographic presentation Washington. which deals with this delightful family. He and his wife Carolyn have Bring your identification skill along lived in Kirkland for the last 40 years. -

PSE's Avian Protection Program Special Thanks

FEBRUARY, 2020 Kitsap Audubon Society – Since 1972 KingfisherTHE February 13, 2020, 7:00 to 9:00 p.m. - Poulsbo Library PSE’s Avian Protection Program For 40 years, Puget Sound Energy has worked to preserve bird habitats and prevent eagles, osprey, hawks, trumpeter swans and other birds from coming into contact with power lines and utility equipment. Puget Sound Energy’s Avian Protection Program promotes a consistent avian-safe system across our eight-county electric service area. While it is not possible to prevent all injurious contact between birds and electric equipment, PSE makes significant investments to reduce the number of incidents. For over 45 years Mel Walters has helped keep birds safe from man-made structures and electrical facilities. As an environmental biologist and consultant he provides expertise in wildlife and wetland The Kingfisher is printed on recycled mitigation, endangered species, paper by Blue Sky Printing and osprey habitat, erosion control mailed by Olympic Presort, both and avian protection. family-owned local businesses. Special thanks . to our Bainbridge Island members and friends for generously designating Kitsap Audubon for a portion of their ONE CALL FOR ALL contributions. Is it okay to feed birds? - Gene Bullock The January snows were of bird seed every year; and a reminder that when we more people watch birds than encourage birds to depend on watch football, baseball and all us for food, we have a special other public sporting events responsibility to them when combined. Some 18 million of snow, ice and sub-freezing us travel to watch birds. Bird temperatures make food harder Watching and related businesses to find. -

Shoreline Inventory and Characterization 2010

KITSAP COUNTY FINAL DRAFT SHORELINE INVENTORY AND CHARACTERIZATION Prepared for and by Kitsap County Department of Community Development, Environmental Programs 614 Division St. Port Orchard, WA 98366 FINAL DRAFT: NOVEMBER 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................................... i 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 SUMMARY OF REPORT CONTENTS AND REFERENCES ........................................... 1 1.1.1 Background ................................................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Characterization Areas .................................................................................. 1 1.1.2.1 Marine Shoreline Summaries (by drift cell) .................................. 2 1.1.2.2 Freshwater Shoreline Summaries (by water body) ...................... 7 1.1.3 1. Recommendations and Management Options ........................................ 11 1.1.4 Public Access and Shoreline Use Analysis ................................................. 11 1.1.5 Characterization Data Gaps ........................................................................ 12 1.1.6 Appendices ................................................................................................. 12 1.2 GLOSSARY and ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................................... -

Draft CCP, Chapters 3-6, November 2012 (Pdf 3.0

Physical Environment Chapter 3 © Mary Marsh Chapter 6 Chapter 5 Chapter 4 Chapter 3 Chapter 2 Chapter 1 Environmental Human Biological Physical Alternatives, Goals, Introduction and Appendices Consequences Environment Environment Environment Objectives, and Strategies Background Dungeness National Wildlife Refuge Draft CCP/EA Chapter 3. Physical Environment 3.1 Climate and Climate Change 3.1.1 General Climate Conditions The climate at Dungeness National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) is a mild, mid-latitude, west coast marine type. Because of the moderating influence of the Pacific Ocean, extremely high or low temperatures are rare. Summers are generally cool and dry while winters are mild but moist and cloudy with most of the precipitation falling between November and January (USDA 1987, WRCC 2011a). Annual precipitation in the region is low due to the rain shadow cast by the Olympic Mountains and the extension of the Coastal Range on Vancouver Island (Figure 3-1). Snowfall is rare or light. During the latter half of the summer and in the early fall, fog banks from over the ocean and the Strait of Juan de Fuca cause considerable fog and morning cloudiness (WRCC 2011a). Climate Change Trends The greenhouse effect is a natural phenomenon that assists in regulating and warming the temperature of our planet. Just as a glass ceiling traps heat inside a greenhouse, certain gases in the atmosphere, called greenhouse gases (GHG), absorb and emit infrared radiation from sunlight. The primary greenhouse gases occurring in the atmosphere include carbon dioxide (CO2), water vapor, methane, and nitrous oxide. CO2 is produced in the largest quantities, accounting for more than half of the current impact on the Earth’s climate. -

Clallam County Community Wildfire Protection Plan

Clallam County Community Wildfire Protection Plan Clallam County Community Wildfire Protection Plan December 2009 Developed by Shea McDonald and Dwight Barry, Peninsula College Center of Excellence. Contributions and developmental assistance: Chris DeSisto, Tiffany Nabors, Erin Drake, and Aaron Lambert; Western Washington University-Peninsulas; Bill Sanders and Bryan Suslick, Washington Department of Natural Resources; Al Knobbs, Clallam County Fire District 3; Jon Bugher, Clallam County Fire District 2; Phil Arbeiter, Clallam County Fire District 1; Larry Nickey, Olympic National Park; Clea Rome, USDA-NRCS; and Dean Millett, US Forest Service. GIS analysis by Shea McDonald, Chris DeSisto, and Dwight Barry. Cartography by Shea McDonald. Project funded under Title III of the Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act of 2000. 1 Table of Contents I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 6 Overview ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Policy Context ............................................................................................................................. 7 Healthy Forests Restoration Act ........................................................................................................... 7 National Fire Plan ................................................................................................................................. -

Chapter 5 Human Environment Appendices

Human Environment Chapter 5 © Dow Lambert Chapter 5 Chapter 4 Chapter 3 Chapter 2 Chapter 1 Human Biological Physical Management Introduction and Appendices Environment Environment Environment Direction Background Dungeness National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan Chapter 5. Human Environment 5.1 Cultural Resources 5.1.1 Native American Overview Prehistory Jeanne M. Welch and R.D. Daugherty prepared a compilation of the prehistoric era on the Olympic Peninsula as part of their background information for a 1988 survey project on Dungeness NWR (Welch and Daugherty 1988). The following information is paraphrased from their report. The five periods of occupation for the region proposed by Eric Bergland (Bergland 1984) cover approximately 12,000 years and include: Early Prehistoric, Middle Prehistoric Early Maritime, Prehistoric, Northwest Coast Pattern, and Historic. On the Olympic Peninsula, the prehistoric people are characterized as small groups of hunters and gatherers who moved around to utilize both terrestrial and maritime resources. This period on the peninsula is represented by the Manis Mastodon site (45CA218) which attests to the hunting of large game animals. It is likely that the onset of the Middle Prehistoric saw an increase in the use of maritime resources such as anadromous fish. By the Early Maritime period, proposed to have begun around 3,000 years before present (BP), the use of maritime resources was well established. It is likely that the cultural manifestations of these later prehistoric periods resembled those of the ethnographic period, but details such as the existence of villages with large, cedar plankhouses are uncertain. During the Prehistoric Northwest Coast Pattern period, which began 1,000 years BP, chipped stone assemblages virtually disappeared while large plankhouse villages became prominent. -

CPB7 C12 WEB.Pdf

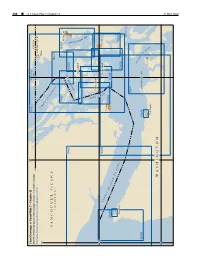

488 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 7, Chapter 12 Chapter 7, Pilot Coast U.S. 124° 123° Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 7—Chapter 12 18421 BOUNDARY NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage BAY CANADA 49° http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml UNITED STATES S T R Blaine 125° A I T O F G E O R V ANCOUVER ISLAND G (CANADA) I A 18431 18432 18424 Bellingham A S S Y P B 18460 A R 18430 E N D L U L O I B N G Orcas Island H A M B A Y H A R O San Juan Island S T 48°30' R A S I Lopez Island Anacortes T 18465 T R A I Victoria T O F 18433 18484 J 18434 U A N D E F U C Neah Bay A 18427 18429 SKAGIT BAY 18471 A D M I R A L DUNGENESS BAY T 18485 18468 Y I N Port Townsend L E T Port Angeles W ASHINGTON 48° 31 MAY 2020 31 MAY 31 MAY 2020 U.S. Coast Pilot 7, Chapter 12 ¢ 489 Strait of Juan De Fuca and Georgia, Washington (1) thick weather, because of strong and irregular currents, ENC - extreme caution and vigilance must be exercised. Chart - 18400 Navigators not familiar with these waters should take a pilot. (2) This chapter includes the Strait of Juan de Fuca, (7) Sequim Bay, Port Discovery, the San Juan Islands and COLREGS Demarcation Lines its various passages and straits, Deception Pass, Fidalgo (8) The International Regulations for Preventing Island, Skagit and Similk Bays, Swinomish Channel, Collisions at Sea, 1972 (72 COLREGS) apply on all the Fidalgo, Padilla, and Bellingham Bays, Lummi Bay, waters of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Haro Strait, and Strait Semiahmoo Bay and Drayton Harbor and the Strait of of Georgia. -

June Beam 2007

The Beam Journal of the New Jersey Lighthouse Society, Inc. www.njlhs.org IN QUEST OF THE KEEPERS Rich & Elinor Veit The restoration of Absecon Lighthouse started house Service shortly after Absecon Lighthouse with a Historic Structure Report. This massive was established as an aide to navigation. John document listed six men who served as light- Nixon stayed on and became the third principal house keepers. However, it also said that there keeper at Absecon. Later Daniel Albertson and were always three keepers at the light station. It Frank Adams, who were brothers-in-law, served was this information, or rather a lack of complete at the same time as assistant keepers. Our re- information, that stirred our curiosity. It set us search found that 26 men and one woman served out on a quest to rebuild the history of the light- as keepers of the lighthouse. The lone woman house keepers to go along with the history of lighthouse keeper was the wife of Abraham Wolf, the lighthouse. principal keeper at that time. Our pursuit took us to quite a number of research At the Heritage Center we also found a treasure facilities. We started with the National Archives trove of photographs of Absecon lighthouse, in Washington, D.C. On microfilm we found the but pictures of only four keepers and none of assignments of the keepers and the dates they their family members. There seems to be an end- served at Absecon, where they came from if they less supply of photographs of the lighthouse, were previously in the Lighthouse Service and but very few of the keepers and their families. -

Geologically Hazardous Areas Map Update for Kitsap County, Washington

Landslide Hazard Deep Landslide Hazard Shallow Landslide Hazard LimitedAreas of More Intense Rural Development Limited Area of More Intense Rural Development -I Type This map was created from existing map sources, not from field surveys. Determination of fitness for use lies with the user, RCW 36.70A.070(5)(d)(i) as does the responsiblity for understanding the accuracy and limitations of this map and data. Mixed use areas or small communities intensively developed The information on this map may have been collected from various sources and can change over time without notice. by 1990, where limited infill development is appropriate. While great care was taken in making this map, there is no guarantee or warranty of its accuracy as to labeling, placement or location of any geographic features present. This map is intended for informational purposes only and is not a substitute Limited Area of More Intense Rural Development -III Type for a field survey. RCW 36.70A.070(5)(d)(i) Kitsap County and its officials and employees assume no responsibility or legal liability for the accuracy, completeness, Lots containing isolated non-residential uses of new development reliability, or timeliness of any information on this map. of isolated cottage indutries and isolated small businesses. Deep seated landslide hazards. Polygons show areas of high and moderate landslide hazards and shallow landslide hazards which polygons show areas of high and moderate shallow landslide hazard. Street Center Lines GRI, 2014, Geologically Hazardous Areas Map Update for Kitsap Washington.County, December 2014. Data source: McMurphy, C.J., 1980, Soil survey of Kitsap County Area, Washington: United States Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service in Cooperation with Washington State Department of Natural Resources. -

Reports 07–08

COASTAL OBSERVATION AND SEABIRD SURVEY TEAM Breaking News Reports 07–08 Better late than never! Swamped with verifying data on Joe Ceriani spotted another rare visitor—an immature 8748 carcasses, 4 special research projects, 25 COASST Glaucous Gull, much more uncommon than its closely trainings and socials, a website meltdown, a bycatch related Glaucous-winged counterpart. Resident to the crisis, staff turnover and a new ‘day job’ for Julia, we Bering and Beaufort Seas, most adult Glaucous Gulls stay admit we fell behind. Actually, way behind. But there was north, even in the winter, but first and second-year birds just so much interesting stuff going on last year, we had appear to move farther south. to let you know. So read fast, because we pledge to get Good thing Joan Christy and Max Blair sent in the this year’s report out early! photos, and a note proclaiming, “this is no April Fools’ joke!” to certify that they indeed found a male Asian Humboldt Ring-necked Pheasant on their April 1st survey. Humboldt COASSTers really felt the heat of being situated next to one of the largest Common Murre Oregon South colonies in the lower 48—between July and October, Big storms throughout the winter months swept away years they cumulatively recorded 360 murres (more than 11 of accumulated sand and gave Barb Holler and Jim and per kilometer in August!). In September, Pete Nelson Charlotte Maloney a chance to see the schooner Bella, and Doug Parkinson not only had quite a slough of a lumber ship blown ashore near Florence, Oregon in murres, but an escapee as well.