November 6, 2020 Submitted Via Email To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Air Quality Tech Report

ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Air Quality Technical Report February, 2020 Table of Contents Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................6 1.0 Project Background ..................................................................................................... 11 1.1 Introduction ...........................................................................................................11 1.1.1 Project Termini .................................................................................................11 1.1.2 Study Area .......................................................................................................11 1.1.3 Purpose and Need ...........................................................................................12 1.2 Alternatives ...........................................................................................................12 1.2.1 No Build Alternative ..........................................................................................12 1.2.2 Build Alternative ...............................................................................................12 1.3 Project Status in the Regional Transportation Plan and Program ..........................14 1.4 Summary of Traffic Data and Forecasts ................................................................15 2.0 Regulatory Requirements and Guidance .................................................................... 18 2.1 National Environmental Policy Act -

Table of Contents

CABIN JOHN CREEK WATERSHED ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT RECOMMENDATIONS FINAL REPORT ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT DIVISION DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS CITY OF ROCKVILLE, MARYLAND Approved July 18, 2011 Center for Watershed Protection KCI Technologies, Inc. CABIN JOHN CREEK WATERSHED ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT RECOMMENDATIONS FINAL REPORT APPROVED JULY 18, 2011 Prepared By: Environmental Management Division Department of Public Works City of Rockville 111 Maryland Avenue Rockville, Maryland 20850 Consultant Services by: KCI Technologies, Inc. Center for Watershed Protection 936 Ridgebrook Road 8390 Main Street, 2nd Floor Sparks, Maryland 21152 Ellicott City, MD 21043 Acknowledgements The Cabin John Creek Watershed Management Plan was initiated by the City of Rockville Department of Public Works, Environmental Management Division. The Project Team consisted of the following City staff and consultants: CITY OF ROCKVILLE STAFF Heather Gewandter, Department of Public Works Michael Critzer, Department of Recreation and Parks Dianne Fasolina, Department of Recreation and Parks Mark Kibiloski, Department of Recreation and Parks John Scabis, P.E., Department of Public Works Lise Soukup, P.E., Project Manager, Department of Public Works Jim Woods, P.E., Department of Public Works KCI TECHNOLOGIES, INC. Susanna Brown Ryan Burdette, P.E. Manasa Damera Nate Drescher Bill Frost, P.E., Project Manager Colin Hill Jackie Krayenvenger, P.E. Bill Medina Mandy O’Shea Mike Pieper Andrea Poling CENTER FOR WATERSHED PROTECTION Kelly Collins Greg Hoffmann, P.E. Julie -

CABIN JOHN CREEK BRIDGE HAER No. MD-95 Clara Barton Parkway Cabin John Vicinity Montgomery County HAE.P- Maryland ^Q

CABIN JOHN CREEK BRIDGE HAER No. MD-95 Clara Barton Parkway Cabin John Vicinity Montgomery County HAE.P- Maryland ^Q 2L- WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD National Park Service Department of the Interior P.O. Box 37127 Washington, D.C. 20013-7127 HAER MD HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD 2>- CABIN JOHN CREEK BRIDGE HAERNo.MD-95 Location: Clara Barton Memorial Parkway milepost 3.44, 1.6 miles from Interstate 495; carries Clara Barton Parkway over Cabin John Creek, in Montgomery County, Maryland, within George Washington Memorial Parkway. FHwA Structure No.: 3300-033P. Date of Construction: 1961 -1963. Type: Reinforced concrete continuous multiple box beam bridge. Designer: Bureau of Public Roads (BPR) and the National Park Service (NPS). BPR Division 15— Site survey, plans and construction observation. William Haussmann, NPS Architectural Designer. F.W. Cron, BPR Regional Engineer. Contractor: Blackwell Construction Co. Present Owner: National Capital Region, National Park Service. Present Use: Noncommercial vehicular traffic of the GWMP over Cabin John Creek and Cabin John Parkway. Significance: One of the best examples of modernist designs for bridges on the GWMP. Project Information: Documentation of the George Washington Memorial Parkway and Clara Barton Parkway was undertaken as a multi-year project by the Historic American Buildings Survey and the Historic American Engineering Record (HABS/HAER), a combined division of the National Park Service, Robert Kapsch, Chief. The project was sponsored by the Park Roads Program of the National Park Service, John Gingles, Deputy Chief, Engineering and Safety Services Division. The Project Supervisor was Sara Amy Leach, HABS Historian. -

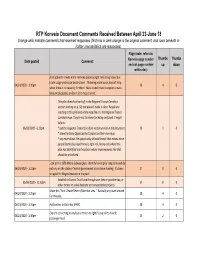

RTP Konveio Document Comments Received Between April 23-June 18

RTP Konveio Document Comments Received Between April 23-June 18 Orange cells indicate comments that received responses (first row in dark orange is the original comment, and rows beneath in lighter orange/italics are responses) Page (note: refers to Thumbs Thumbs Date posted Comment Konveio page number and not page number up down within doc) Add option to create more rail lines (subway/light rail) along heavy bus route usage and major destinations. Throwing more buses doesn't help 04/24/2020 - 1:20pm 26 4 0 when there is no capacity for them. Mass transit must transport a mass amount of people, or else it isn't mass transit. This plan does that (sort of) in the Regional Transit Corridors section starting on p. 58, but doesn't make it clear. People are reacting to this pink and white map like it is the Regional Transit Corridors map. They're not to blame for being confused. It might help to: 06/03/2020 - 6:12pm * put the Regional Transit Corridors section earlier in the document 26 1 0 * show the Early Opportunity Corridors on their own map * say more about the opportunity to build transit that moves more people faster (bus rapid transit, light rail, heavy rail) where this plan has identified are the places where improvements like that should be prioritized Look at the 1978 Metro Subway plan. Identify funding for long term and do 04/24/2020 - 1:22pm not rely on the state or federal government to continue funding. It's been 27 8 0 stripped for illogical reasons in the past! Establish a Transit Trust Fund through user fees or gasoline tax, or 05/06/2020 - 11:50pm 27 8 0 other means to solely dedicate to transportation projects. -

Transportation and Environment Committee FROM

T&E COMMITTEE #1 June 15, 2020 M E M O R A N D U M June 11, 2020 TO: Transportation and Environment Committee FROM: Glenn Orlin, Senior Analyst SUBJECT: Managed Lanes Study’s Transit Service Coordination Report1 PURPOSE: Briefing The Maryland Department of Transportation (MDOT) has completed a study to identify how transit could maximize the utility of proposed managed lanes on I-270 and I-495. The Managed Lanes Transit Work Group, consisting of staffs from FTA, FHWA, MTA, WMATA, COG, and several counties in Maryland (including Montgomery County DOT) was convened in May 2019 to advise on the study. The study conducted a transit market analysis to determine how existing bus routes could be modified and enhanced, what new bus routes could be initiated, a review of managed lane access points, potential transit center and park-and-ride locations, and the potential for enhanced carpooling. The study and its appendix are here: https://495-270-p3.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Transit- Coordination-Report-May-2020.pdf. MDOT’s presentation is attached on ©1-28 and will be led by: Lisa Choplin, Director, I-495 & I-270 P3 Office, MDOT Jeff Folden, Deputy Director, I-495 & I-270 P3 Office, MDOT Jim Ritchey, Vice President, Whitman, Requardt & Associates, LLP (Transit Work Group Lead) DOT Director Christopher Conklin and Transit Services Chief Dan Hibbert, who participated in the Work Group, have also been invited to provide comment and answer questions directed to them. The locations of the access points are of particular interest, in that these would be where toll- paying motor vehicles and transit buses would be able to reach or depart from the managed lanes without the lost time of weaving back and forth across several congested general-use lanes. -

Silver Spring Downtown Plan Boundary

April 20, 2020 Montgomery Planning Board 8787 Georgia Ave Silver Spring, MD 20910 Re: Silver Spring Downtown Plan Boundary Dear Chair Anderson and Planning Commissioners, Please accept these comments on behalf of the Coalition for Smarter Growth, the leading organization in the DC region advocating for more walkable, inclusive, transit-oriented communities. We support expanding the boundary of the Silver Spring Downtown Plan to include neighborhoods within a reasonable walking distance of certain Metrorail, Purple Line, and Flash stations. Specifically, we urge you to consider including properties within a: 20-25 minute walk of the Silver Spring Transit Center 15-20 minute walk of the future 16th Street, Silver Spring Library, and Dale Drive Purple Line stations 10-15 minute walk of the future Fenton Street Flash station The Silver Spring Downtown Plan update is an opportunity for the Planning Board to embrace missing middle housing and the new “complete communities” concept proposed in Thrive Montgomery 2050. Mixed-use communities with different types of homes to rent or buy are more affordable and sustainable, enabling people from all walks of life and all incomes to live without relying on a personal vehicle. Furthermore, including neighborhoods abutting the current central business district (CBD) will allow for a better flow of the built environment. Currently, many high-rise buildings within the CBD are adjacent to single family homes. Silver Spring would greatly benefit from “gentle density” connecting high-rise clusters with lower density neighborhoods. East Silver Spring, adjacent to the CBD, already offers an example of a neighborhood with an array of townhomes, duplexes, and small apartment buildings. -

Rockville Memorial Library Tuesday, October 29, 2019 Maryland- National Capital Parks and Planning Commission Administration Building Tuesday, November 12, 2019

Washington Suburban Transit Commission Public Forum ROCKVILLE MEMORIAL LIBRARY TUESDAY, OCTOBER 29, 2019 MARYLAND- NATIONAL CAPITAL PARKS AND PLANNING COMMISSION ADMINISTRATION BUILDING TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 12, 2019 WASHINGTON SUBURBAN TRANSIT COMMISSION Washington Suburban Transit Commission - Composition Seven Commissioners: three appointees each from Prince George’s and Montgomery counties plus the Maryland Secretary of Transportation (ex officio). Montgomery County Prince George’s County Mr. Michael Goldman (Chair) VACANT • Appointed by Gov. O’Malley in 2013. Re- • Gubernatorial appointment appointed by Gov. Hogan in 2017 • Also principal Director on the WMATA Board • Also principal Director on the WMATA Board Ms. Kathryn Porter Mr. Thomas Graham • Appointed by County Exec. Alsobrooks in 2019 • Appointed by County Exec. Leggett in 2013 • Also alternate Director on the WMATA Board • Also alternate Director on the WMATA Board Mr. Hoan Dang Councilman Todd Turner • Appointed by County Exec. Leggett in 2013 • Appointed by the County Council in 2013 • Only elected official on the Commission WASHINGTON SUBURBAN TRANSIT COMMISSION 2 Washington Suburban Transit Commission - Composition Michael Goldman (Chair) Kathryn Porter Vacant Thomas Graham WMATA Director WMATA alternate Director WMATA Director WMATA alternate Director Hoan Dang Sec. Pete Rahn Hon. Todd Turner WMATA Director WASHINGTON SUBURBAN TRANSIT COMMISSION 3 Background and County Coordination •Created in 1965 by an act of the Maryland General Assembly. •Bi-county agency: codified -

Create a Balanced Transportation System

Transportation Briefing Silver Spring Citizens Advisory Board Al Roshdieh, Director September 9, 2019 MCDOT Priorities • Create a Balanced Transportation System ➢ Road Network ➢ Transit ➢ Bicycle & Pedestrian Mobility • Promote Economic Development & Smart Growth • Involve & Support Our Community Priority: Create a Balanced Transportation System County road network • MD 355 Crossing • White Flint Western Workaround • Seminary Road • Snouffer School Road • Infrastructure maintenance • Parking improvements Priority: Create a Balanced Transportation System State road network project status • I-270 Integrated Corridor Management – under construction • I-270 / I-495 Managed Lanes Project – alternatives retained for detailed study (including MD 200 diversion alternative) • I-270 / Watkins Mill Interchange – under construction • MD 97 / Montgomery Hills – study phase nearly completed • MD 97 / Brookeville Bypass – under construction • MD 97 at Randolph Road Interchange – complete • BRAC Intersection Improvements / MD185 at Jones Bridge Road – utility relocation in process • US 29 – Mobility & Reliability Study – results expected fall 2019 Priority: Create a Balanced Transportation System Transit: Ride On • Wi-Fi on all buses • Kids Ride Free all the time • New Ride On Flex on-demand transit pilot • Limited-stop Ride On Extra service on MD 355 • Westfield Montgomery and Takoma- Langley Transit Centers • 65 new Ride On buses since July 2017 • Real time transit screens Priority: Create a Balanced Transportation System Transit • Purple Line • US 29 FLASH BRT • MD 355 FLASH BRT • Veirs Mill Road FLASH BRT • New Hampshire Avenue FLASH BRT • Corridor Cities Transitway • North Bethesda Transitway Priority: Create a Balanced Transportation System Transit: Purple Line • 16.2 miles - under construction across the alignment from Bethesda to New Carrollton. Projected to last through 2022. -

Adopted Operating Budget Capital Improvements Program&

Fiscal Year 2022 2022CITY OF ROCKVILLE, MARYLAND Adopted Operating Budget Capital Improvements Program& JULY 1, 2021 – JUNE 30, 2022 111 MARYLAND AVENUE, ROCKVILLE, MARYLAND 20850 | 240-314-5000 | WWW.ROCKVILLEMD.GOV FY 2022 Adopted Operating Budget and Capital Improvements Program July 2021 Bridget Donnell Newton, Mayor Monique Ashton, Councilmember Beryl L. Feinberg, Councilmember David Myles, Councilmember Mark Pierzchala, Councilmember Robert DiSpirito, City Manager Cynthia Walters, Acting City Attorney Sara Taylor-Ferrell, City Clerk/Director of Council Operations Prepared by the Department of Finance and the Staff of the City of Rockville Gavin Cohen, Chief Financial Officer/Director of Finance Stacey Webster, Deputy Chief Financial Officer Mary Sue Martin, Senior Management and Budget Analyst Daniel Chambers, Management and Budget Analyst Ricky Barker, Director of Planning and Development Services Victor Brito, Chief of Police Timothy J. Chesnutt, Director of Recreation and Parks Asmara Habte, Director of Housing and Community Development Angela Judge, Deputy City Manager Karen Marshall, Director of Human Resources Nicholas Obodo, Chief Information Officer Craig L. Simoneau, PE, Director of Public Works City of Rockville, Maryland FY 2022 Adopted Budget Table of Contents Introduction CIP Overview City Manager's Transmittal Letter 11 Capital Improvements Program Structure 265 Vision and Priorities for FY 2022 13 Capital Improvements Program Overview 266 FY 2022 Budget-In-Brief 18 CIP Prioritization Process 267 The Budget Process -

Silver Spring Downtown Plan Boundary Dear

April 20, 2020 Montgomery Planning Board 8787 Georgia Ave Silver Spring, MD 20910 Re: Silver Spring Downtown Plan Boundary Dear Chair Anderson and Planning Commissioners, Please accept these comments on behalf of the Coalition for Smarter Growth, the leading organization in the DC region advocating for more walkable, inclusive, transit-oriented communities. We support expanding the boundary of the Silver Spring Downtown Plan to include neighborhoods within a reasonable walking distance of certain Metrorail, Purple Line, and Flash stations. Specifically, we urge you to consider including properties within a: 20-25 minute walk of the Silver Spring Transit Center 15-20 minute walk of the future 16th Street, Silver Spring Library, and Dale Drive Purple Line stations 10-15 minute walk of the future Fenton Street Flash station The Silver Spring Downtown Plan update is an opportunity for the Planning Board to embrace missing middle housing and the new “complete communities” concept proposed in Thrive Montgomery 2050. Mixed-use communities with different types of homes to rent or buy are more affordable and sustainable, enabling people from all walks of life and all incomes to live without relying on a personal vehicle. Furthermore, including neighborhoods abutting the current central business district (CBD) will allow for a better flow of the built environment. Currently, many high-rise buildings within the CBD are adjacent to single family homes. Silver Spring would greatly benefit from “gentle density” connecting high-rise clusters with lower density neighborhoods. East Silver Spring, adjacent to the CBD, already offers an example of a neighborhood with an array of townhomes, duplexes, and small apartment buildings. -

AIM) Demonstration

Accelerating Innovative Mobility (AIM) Demonstration Travel Rewards Research Pilot Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (LA Metro) Los Angeles, CA Team and Budget Key Partners: Duke University Center for Advanced Hindsight, Harvard School of Business, Uber, Waze Carpool, Rideamigos, Transit App, Metropia Budget Summary: AIM Demonstration Federal Amount AIM Demonstration Cost Share Total Cost $700,000 $587,000 $1,287,000 Innovation: Project Approach As part of overall post COVID-19 crisis recovery plans, this research pilot seeks to encourage people back to public transit by incentivizing forms of mobility other than driving alone. LA Metro, together with the leading behavioral economics researchers at the Duke Center for Advanced Hindsight and Harvard School of Business, will partner with mobility technology firms to develop a research pilot to identify the most cost- effective incentive to shift single-occupancy vehicle (SOV) trips to public transit or another non-SOV mode (shared ride-hail, carpool, vanpool, walk, bike, telecommute) and understand the best way to structure, deliver, and time incentives to get the best return on investment (ROI). The pilot will also leverage existing public transit, microtransit, and multimodal programs managed by Metro and its countywide partners and will support fare integration between Metro’s Transit Access Pass (TAP) with private mobility providers. Research results will inform transportation demand management (TDM) policies for LA County and nationwide. The idea for the pilot came from a 2018 forum hosted by Metro’s Office of Extraordinary Innovation called “Think You Can Solve Traffic?” designed to solicit private industry solutions to solving traffic problems in LA County. -

MD 355 BRT Corridor Planning Study Phase 2 Public and Stakeholder Engagement Summary

MD 355 BRT Corridor Planning Study Phase 2 Public and Stakeholder Engagement Summary October 2019 Public and Stakeholder Engagement Summary Table of Contents 1 Introduction ...............................................................................................................................1 1.1 MD 355 BRT Project Purpose and Need ........................................................................................... 1 2 Alternatives ................................................................................................................................2 2.1 No-Build Alternative.......................................................................................................................... 2 2.2 Transportation System Management (TSM) Alternative .................................................................. 2 2.3 Alternative A ..................................................................................................................................... 2 2.4 Alternative B and B Modified ............................................................................................................ 2 2.5 Alternative C ..................................................................................................................................... 3 2.6 Alignment Segments ......................................................................................................................... 3 3 Public and Stakeholder Engagement: Overview Summary ............................................................5