A Clinician's Plea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Complete Genome Sequence of Mycobacterium Avium Subspecies Paratuberculosis

The complete genome sequence of Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis Lingling Li*†‡, John P. Bannantine‡§, Qing Zhang*†‡, Alongkorn Amonsin*†‡, Barbara J. May*†, David Alt§, Nilanjana Banerji†¶, Sagarika Kanjilal†‡¶, and Vivek Kapur*†‡ʈ *Department of Microbiology, †Biomedical Genomics Center, and ¶Department of Medicine, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN 55108; and §National Animal Disease Center, U.S. Department of Agriculture–Agriculture Research Service, Ames, IA 50010 Communicated by Harley W. Moon, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, July 13, 2005 (received for review March 18, 2005) We describe here the complete genome sequence of a common Map and Mav (11–13). Therefore, it is widely recognized that the clone of Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (Map) development of rapid, sensitive, and specific assays to identify strain K-10, the causative agent of Johne’s disease in cattle and infected animals is essential to the formulation of rational other ruminants. The K-10 genome is a single circular chromosome strategies to control the spread of Map. of 4,829,781 base pairs and encodes 4,350 predicted ORFs, 45 As a first step toward elucidating the molecular basis of Map’s tRNAs, and one rRNA operon. In silico analysis identified >3,000 physiology and virulence, and providing a foundation for the genes with homologs to the human pathogen, M. tuberculosis development of the next generation of Map diagnostic tests and (Mtb), and 161 unique genomic regions that encode 39 previously vaccines, we report the complete genome sequence of a common unknown Map genes. Analysis of nucleotide substitution rates clone of Map, strain K-10. with Mtb homologs suggest overall strong selection for a vast majority of these shared mycobacterial genes, with only 68 ORFs Materials and Methods with a synonymous to nonsynonymous substitution ratio of >2. -

Molecular Genetics of Microcephaly Primary Hereditary: an Overview

brain sciences Review Molecular Genetics of Microcephaly Primary Hereditary: An Overview Nikistratos Siskos † , Electra Stylianopoulou †, Georgios Skavdis and Maria E. Grigoriou * Department of Molecular Biology & Genetics, Democritus University of Thrace, 68100 Alexandroupolis, Greece; [email protected] (N.S.); [email protected] (E.S.); [email protected] (G.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected] † Equal contribution. Abstract: MicroCephaly Primary Hereditary (MCPH) is a rare congenital neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by a significant reduction of the occipitofrontal head circumference and mild to moderate mental disability. Patients have small brains, though with overall normal architecture; therefore, studying MCPH can reveal not only the pathological mechanisms leading to this condition, but also the mechanisms operating during normal development. MCPH is genetically heterogeneous, with 27 genes listed so far in the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database. In this review, we discuss the role of MCPH proteins and delineate the molecular mechanisms and common pathways in which they participate. Keywords: microcephaly; MCPH; MCPH1–MCPH27; molecular genetics; cell cycle 1. Introduction Citation: Siskos, N.; Stylianopoulou, Microcephaly, from the Greek word µικρoκεϕαλi´α (mikrokephalia), meaning small E.; Skavdis, G.; Grigoriou, M.E. head, is a term used to describe a cranium with reduction of the occipitofrontal head circum- Molecular Genetics of Microcephaly ference equal, or more that teo standard deviations -

The Yin and Yang of Autosomal Recessive Primary Microcephaly Genes: Insights from Neurogenesis and Carcinogenesis

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review The Yin and Yang of Autosomal Recessive Primary Microcephaly Genes: Insights from Neurogenesis and Carcinogenesis Xiaokun Zhou 1, Yiqiang Zhi 1, Jurui Yu 1 and Dan Xu 1,2,* 1 College of Biological Science and Engineering, Institute of Life Sciences, Fuzhou University, Fuzhou 350108, China; [email protected] (X.Z.); [email protected] (Y.Z.); [email protected] (J.Y.) 2 Fujian Key Laboratory of Molecular Neurology, Institute of Neuroscience, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou 350005, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-17085937559 Received: 17 December 2019; Accepted: 26 February 2020; Published: 1 March 2020 Abstract: The stem cells of neurogenesis and carcinogenesis share many properties, including proliferative rate, an extensive replicative potential, the potential to generate different cell types of a given tissue, and an ability to independently migrate to a damaged area. This is also evidenced by the common molecular principles regulating key processes associated with cell division and apoptosis. Autosomal recessive primary microcephaly (MCPH) is a neurogenic mitotic disorder that is characterized by decreased brain size and mental retardation. Until now, a total of 25 genes have been identified that are known to be associated with MCPH. The inactivation (yin) of most MCPH genes leads to neurogenesis defects, while the upregulation (yang) of some MCPH genes is associated with different kinds of carcinogenesis. Here, we try to summarize the roles of MCPH genes in these two diseases and explore the underlying mechanisms, which will help us to explore new, attractive approaches to targeting tumor cells that are resistant to the current therapies. -

Allwithnames.Pdf

Erythrocytes take up oxygen and release carbon dioxide AL1A1 ADH6ADHXADH7 ADH1G ADH1B ADH4 AL1B1 Cyclin E associated events during G1/S transition FRS-mediated FGFR4 signaling ADH1A CP2E1CP2B6 CP2A6 CP2CJCP2C8 CP2AD CP2C9 CP2D6 Pyrimidine salvageKHK TRP channels AL1A3 CP2J2Fanconi Anemia Pathway AL1A2 I23O1KMO Synthesis of bile acids and bile HYESsalts via 27-hydroxycholesterol AADATKYNUT23O Cobalamin (Cbl, vitamin B12) transport and metabolism CP3A5 ARMS-mediated activation Syndecan interactionsCP3A4 CP1A2 Tryptophan catabolism PANK3PANK2 Abacavir metabolism PANK1 Advanced glycosylation endproduct receptor signaling KCNK3 KCNK9 Loss of ALDH2proteins required for interphase microtubule organization from the centrosome XAV939 inhibits tankyrase, stabilizing AXIN Phase 2 - plateau phase KCNK2 Orc1 removal from chromatin Mineralocorticoid biosynthesis S22A6 S22ABS22AC CP26A Truncations of AMER1 destabilize the destruction complex Cytosolic sensorsPurine ribonucleoside of pathogen-associated monophosphate DNA biosynthesis ST1E1 UMPSPYRD CholineCGAT1 catabolism TPST2ST1A1 Separation ofTPH1 Sister Chromatids Methionine INMTsalvage pathway Phase 4 - restingHPPD membrane potential Classical antibody-mediatedKCNJ4 complement activation Phase I - Functionalization of compounds KCNJ2 Cargo recognition for clathrin-mediatedBODG endocytosis ENTP3ENTP1 CP1B1 ADAL ENTP2 CD38 Costimulation by the CD28 family N-glycan trimming in the ER and Calnexin/Calreticulin cycle METK2TPMT BHMT1 PGH1 Metalloprotease DUBs Retrograde neurotrophin signalling DHSO Caspase-mediated -

The Development of a Statistical Model to Study How the Deletion of PD-1 Promotes Anti-Tumor Immunity

The Development of a Statistical Model to Study How the Deletion of PD-1 Promotes Anti-Tumor Immunity The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Diallo, Alos Burgess. 2021. The Development of a Statistical Model to Study How the Deletion of PD-1 Promotes Anti-Tumor Immunity. Master's thesis, Harvard University Division of Continuing Education. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37367694 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Development of a Statistical Model to Study How the Deletion of PD-1 Promotes Anti-Tumor Immunity Alos Diallo A Thesis in the Field of Bioinformatics for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University March 2021 1 2 Copyright 2021 [Alos Diallo] Abstract T-cells are an essential component to the immune system, but they do not act alone and are instead a component in the body’s immune system. PD-1 and its ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2 play an important role in the regulation of T-cells which are incredibly important to the treatment of cancer. Tumors have been able to hijack the PD-1 inhibitory pathway to evade our body’s immune response. PD-1 pathway blockade, therefore, can serve as an important approach for cancer immunotherapy. -

Protein from Sulfolobus Shibatae Sohail A

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UCL Discovery 1995 Oxford University Press Nucleic Acids Research, 1995, Vol. 23, No. 10 1775-1781 Cloning and functional analysis of the TATA binding protein from Sulfolobus shibatae Sohail A. Qureshi, Peter Baumann, Tracey Rowlands, Bernard Khoo and Stephen P. Jackson* Wellcome/CRC Institute, Tennis Court Road, Cambridge CB2 1 QR, UK and Department of Zoology, Cambridge University, Cambridge, UK Received January 19, 1995; Revised and Accepted March 28, 1995 GenBank accession no. U2341 9 ABSTRACT Eucarya and Bacteria, relatively little work has been conducted on archaeal transcription systems. Over the past few years, Archaea (formerly archaebacteria) comprise a domain however, several lines of evidence have suggested that the of life that is phylogenetically distinct from both transcription systems of Archaea and Eucarya are fundamentally Eucarya and Bacteria. Here we report the cloning of a homologous. Although Archaea possess just one DNA-dependent gene from the Archaeon Sulfolobus shibatae that RNA polymerase, this enzyme consists of -12 subunits and is encodes a protein with strong homology to the TATA therefore similar in its structural complexity to eukaryotic nuclear binding protein (TBP) of eukaryotes. Sulfolobus RNA polymerases (4). In contrast, bacterial RNA polymerases shibatae TBP is, however, almost as diverged from other archaeal TBPs that have been cloned as it is from contain three core subunits (X, e and 'Y, and a tightly associated eukaryotic TBPs. DNA binding studies indicate that a factor (5). Immunochemical and sequence analyses have S.shibatae TBP recognizes TATA-like A-box sequences revealed that the two largest RNA polymerase subunits of that are present upstream of most archaeal genes. -

The Mitotic Apparatus and Kinetochores in Microcephaly and Neurodevelopmental Diseases

cells Review The Mitotic Apparatus and Kinetochores in Microcephaly and Neurodevelopmental Diseases 1, , 2 1, , Francesca Degrassi * y , Michela Damizia and Patrizia Lavia * y 1 IBPM Institute of Molecular Biology and Pathology, CNR Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, c/o Department of Biology and Biotechnology “Charles Darwin”, Sapienza University of Rome, 00185 Roma, Italy 2 Department of Biology and Biotechnology “Charles Darwin”, Sapienza University of Rome, 00185 Roma, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (F.D.); [email protected] (P.L.); Tel.: +39-06-49917517 (F.D.); +39-06-49917536 (P.L.) These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 20 November 2019; Accepted: 21 December 2019; Published: 24 December 2019 Abstract: Regulators of mitotic division, when dysfunctional or expressed in a deregulated manner (over- or underexpressed) in somatic cells, cause chromosome instability, which is a predisposing condition to cancer that is associated with unrestricted proliferation. Genes encoding mitotic regulators are growingly implicated in neurodevelopmental diseases. Here, we briefly summarize existing knowledge on how microcephaly-related mitotic genes operate in the control of chromosome segregation during mitosis in somatic cells, with a special focus on the role of kinetochore factors. Then, we review evidence implicating mitotic apparatus- and kinetochore-resident factors in the origin of congenital microcephaly. We discuss data emerging from these works, which suggest a critical role of correct mitotic division in controlling neuronal cell proliferation and shaping the architecture of the central nervous system. Keywords: microcephaly; mitotic apparatus; kinetochore; chromosome segregation; neural progenitors 1. Introduction Regulators of the mitotic apparatus play key roles in orchestrating chromosome segregation. -

Ankhd1 Enhances Polycystic Kidney Disease Development Via Promoting Proliferation and Fibrosis

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.04.977017; this version posted March 6, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Ankhd1 enhances polycystic kidney disease development via promoting proliferation and fibrosis. Foteini Patera1✦, Guillaume M Hautbergue2, Patricia Wilson3, Paul C Evans1, Albert CM 1 1☆ Ong , Maria Fragiadaki . 1 Department of Infection Immunity and Cardiovascular disease, University of Sheffield Medical School, Sheffield, UK. 2Sheffield Institute for Translational Neuroscience, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK. 3 University College London Centre for Nephrology, University College London, London, United Kingdom. ☆Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to MF (email: [email protected]) Running title: ANKHD1 is a novel driver of ADPKD -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ABSTRACT Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (ADPKD) is the most common genetic kidney disorder resulting in 10% of patients with renal failure. The molecular events responsible for the relentless growth of cysts are not defined. Thus, identification of novel drivers of ADPKD may lead to new therapies. Ankyrin Repeat and Single KH domain-1 (ANKHD1) controls cancer cell proliferation, yet its role in ADPKD is unexplored. Here, we present the first data that identify ANKHD1 as a driver of proliferative growth in cellular and mouse models of ADPKD. Using the first Ankhd1-deficient mice, we demonstrate that Ankhd1 heterozygosity potently reduces cystic growth and fibrosis, in a genetically orthologous mouse model of ADPKD. We performed transcriptome-wide profiling of patient-derived ADPKD cells with and without ANKHD1 siRNA silencing, revealing a major role for ANKHD1 in the control of cell proliferation and matrix remodelling. -

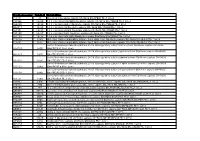

Protein List

Protein Accession Protein Id Protein Name P11171 41 Protein 4. -

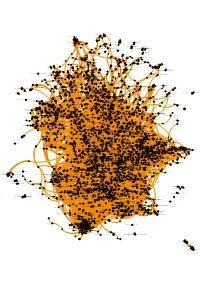

A Physical Map of the Human Genome

articles A physical map of the human genome The International Human Genome Mapping Consortium* * A partial list of authors appears at the end of this paper. A full list is available as Supplementary Information. ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ The human genome is by far the largest genome to be sequenced, and its size and complexity present many challenges for sequence assembly. The International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium constructed a map of the whole genome to enable the selection of clones for sequencing and for the accurate assembly of the genome sequence. Here we report the construction of the whole-genome bacterial arti®cial chromosome (BAC) map and its integration with previous landmark maps and information from mapping efforts focused on speci®c chromosomal regions. We also describe the integration of sequence data with the map. The International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium Construction of the whole-genome BAC map (IHGSC) used a hierarchical mapping and sequencing strategy to The pilot phase of the sequencing project began in 1995, at which construct the working draft of the human genome. This clone-based time efforts were renewed to develop clone-based maps covering approach involves generating an overlapping series of clones that speci®c regions of the genome. To construct these regional maps, we covers the entire genome. Each clone is `®ngerprinted' on the basis screened PAC and BAC clones for STS markers, ®ngerprinted the of the pattern of fragments generated by restriction enzyme positive clones, integrated them into the existing maps, and selected digestion1,2. Clones are then selected for shotgun sequencing and the largest, intact clones with minimal overlap for sequencing. -

Feature-Expression Heat Maps 51

University of Groningen The Dysregulated Brain Haarman, Bartholomeus Cornelius Maria IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2017 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Haarman, B. C. M. (2017). The Dysregulated Brain: A psychoimmunological approach to bipolar disorder. University of Groningen. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 04-10-2021 The Dysregulated Brain -

(Linoleate/Oleate) Stimulates Prodifferentiation Gene Expression to Restore the Epidermal Barrier and Improve Skin Hydration Krzysztof Bojanowski1,2, William R

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Isosorbide Di-(Linoleate/Oleate) Stimulates Prodifferentiation Gene Expression to Restore the Epidermal Barrier and Improve Skin Hydration Krzysztof Bojanowski1,2, William R. Swindell3, Shyla Cantor4 and Ratan K. Chaudhuri2,5 The breakdown of the epidermal barrier and consequent loss of skin hydration is a feature of skin aging and eczematous dermatitis. Few treatments, however, resolve these underlying processes to provide full symp- tomatic relief. In this study, we evaluated isosorbide di-(linoleate/oleate) (IDL), which was generated by esterifying isosorbide with sunflower fatty acids. Topical effects of IDL in skin were compared with those of ethyl linoleate/oleate, which has previously been shown to improve skin barrier function. Both IDL and ethyl linoleate/oleate downregulated inflammatory gene expression, but IDL more effectively upregulated the expression of genes associated with keratinocyte differentiation (e.g., KRT1, GRHL2, SPRR4). Consistent with this, IDL increased the abundance of epidermal barrier proteins (FLG and involucrin) and prevented cytokine- mediated stratum corneum degradation. IDL also downregulated the expression of unhealthy skin signature genes linked to the loss of epidermal homeostasis and uniquely repressed an IFN-inducible coexpression module activated in multiple skin diseases, including psoriasis. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial enrolling females with dry skin, 2% IDL lotion applied over 2 weeks significantly improved skin hydration and decreased transepidermal water loss (NCT04253704). These results demonstrate mechanisms by which IDL improves skin hydration and epidermal barrier function, supporting IDL as an effective intervention for the treatment of xerotic pruritic skin. Journal of Investigative Dermatology (2021) 141, 1416e1427; doi:10.1016/j.jid.2020.09.029 INTRODUCTION treatments and may be combined with topical corticosteroids Skin barrier defects may occur with aging or because of or oral antihistamines (Anderson and Dinulos, 2009; Elias chronic inflammatory skin diseases.