Use and Appreciation of a Web-Based, Tailored Intervention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning the Horticultural Sector Managing Greenhouse Sprawl in the Netherlands

Planning the Horticultural Sector Managing Greenhouse Sprawl in the Netherlands Korthals Altes, W.K., Van Rij, E. (2013) Planning the horticultural sector: Managing greenhouse sprawl in the Netherlands, Land Use Policy, 31, 486-497 Abstract Greenhouses are a typical example of peri-urban land-use, a phenomenon that many planning systems find difficult to address as it mixes agricultural identity with urban appearance. Despite its urban appearance, greenhouse development often manages to evade urban containment policies. But a ban on greenhouse development might well result in under-utilisation of the economic value of the sector and its potential for sustainability. Specific knowledge of the urban and rural character of greenhouses is essential for the implementation of planning strategies. This paper analyses Dutch planning policies for greenhouses. It concludes with a discussion of how insights from greenhouse planning can be applied in other contexts involving peri-urban areas. Keywords: greenhouses; horticulture; land-use planning; the Netherlands; peri-urban land-use 1 Introduction The important role played by the urban-rural dichotomy in planning practice is a complicating factor in planning strategies for peri-urban areas, often conceptualised as border areas (the rural-urban fringe) or as an intermediate zone between city and countryside (the rural-urban transition zone) (Simon, 2008). However, “[t]he rural-urban fringe has a special, and not simply a transitional, land-use pattern that distinguishes it from more distant countryside and more urbanised space.” (Gallent and Shaw, 2007, 621) Planning policies tend to overlook this specific peri-environment, focusing rather on the black-and-white difference between urban and rural while disregarding developments in the shadow of cities (Hornis and Van Eck, 2008). -

MEREPUV Working Paper from Safety Region South Holland South D3.2 SRSHS

MEREPUV Working Paper from Safety Region South Holland South D3.2 SRSHS Approved by Date 1 Content 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Project MEREPUV ................................................................................................................................ 4 Overall goals of the project ................................................................................................................. 4 Scenarios ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Overall description of methods, process, data collection ................................................................... 4 Affect of the scenarios on other vital functions .................................................................................. 5 Affect on health services ..................................................................................................................... 5 Insight in Cascading effects and consequences for other vital societal functions .............................. 5 2 About power outages in the Netherlands ............................................................................................ 6 Facts about reliability in deliverance of power in the Netherlands .................................................... 6 Facts about incidents of previous power outages ............................................................................. -

The Cheese Markets of the Netherlands by Lee Foster

The Cheese Markets of the Netherlands by Lee Foster Few experiences satisfy the person who savors food and drink more than a journey to the source, the place where a favorite wine, cheese, or fruit is produced. The encounter imparts a knowledge of terrain and an appreciation of techniques used to make the prized food or drink. No book can teach this experience; no number of trips to the local delicatessen or bottle shop can equal it. For the appreciator of cheese, Dutch cheese is one of the gustatory glories of the Netherlands. The place to start is a good cheese store in Amsterdam. Beyond Amsterdam, you can visit the cheese markets at Alkmaar and at Gouda. You can also visit a cheese-making farm, Clara Maria, near Amsterdam. Details can be easily arranged by the Netherlands Board of Tourism office, www.holland.com. Cheese Shops in Amsterdam Cheese shops in Amsterdam, such as Abraham Kef’s, 192 Marninxstraat, are the places to make your first encounter with Dutch cheeses. At Kef’s you can make a tasting ceremony of cheese and wine. First, try a slice of Gouda, which is 60 percent of all the cheese produced in the Netherlands. Half of this Gouda is exported, making the Dutch one of the world’s largest exporters of cheese. Ask for a piece of Young Gouda, about three months old, which is imported to the U.S. labeled Young or Mild Gouda. Most Goudas are whole milk cheeses with a fat content of 48 percent. The Young Gouda has a creamy, buttery taste. -

A Short History of Holland, Belgium and Luxembourg

A Short History of Holland, Belgium and Luxembourg Foreword ............................................................................2 Chapter 1. The Low Countries until A.D.200 : Celts, Batavians, Frisians, Romans, Franks. ........................................3 Chapter 2. The Empire of the Franks. ........................................5 Chapter 3. The Feudal Period (10th to 14th Centuries): The Flanders Cloth Industry. .......................................................7 Chapter 4. The Burgundian Period (1384-1477): Belgium’s “Golden Age”......................................................................9 Chapter 5. The Habsburgs: The Empire of Charles V: The Reformation: Calvinism..........................................10 Chapter 6. The Rise of the Dutch Republic................................12 Chapter 7. Holland’s “Golden Age” ..........................................15 Chapter 8. A Period of Wars: 1650 to 1713. .............................17 Chapter 9. The 18th Century. ..................................................20 Chapter 10. The Napoleonic Interlude: The Union of Holland and Belgium. ..............................................................22 Chapter 11. Belgium Becomes Independent ...............................24 Chapter 13. Foreign Affairs 1839-19 .........................................29 Chapter 14. Between the Two World Wars. ................................31 Chapter 15. The Second World War...........................................33 Chapter 16. Since the Second World War: European Co-operation: -

Lepidoptera Van Goeree-Overflakkee

ENTOMOLOGISCHE BERICHTEN, DEEL 25, 1.VIII. 1965 153 Lepidoptera van Goeree-Overflakkee door K. J. HUISMAN Op de 97ste Winterverga¬ dering toonde ik de volgende Lepidoptera : 1. Porphyrinia parva Hüb¬ ner. Het eerste Nederlandse exemplaar, dat hierbij ook af- gebeeld wordt, werd 13 juni 1964 overdag op een zonnige dijkhelling te Melissant ge¬ vangen. Het dier werd opge¬ jaagd en zette zich even ver¬ A. VAN DER SlUIJS der weer neer. Klaarblijkelijk Porphyrinia parva Hb., $, Melissant 1964; X 3V,. waren de omstandigheden voor deze soort gunstig, want later in het jaar was de heer van Aartsen zo gelukkig nog een tweede exem¬ plaar te vangen. De nauw verwante Porphyrinia ostrina Hübner werd, zoals bekend is, in 1958 gevangen (zie J. H. Küchlein, Ent. Ber. 19 : 135, 1959). 2. Catoptria fulgidella Hübner. In 1964 in meerdere exemplaren te Ouddorp gevangen. 3. Heterogr aphis ohlitella Zeiler. De soort blijkt zowel te Melissant als te Oud¬ dorp geregeld voor te komen. 4. Phlyctaenia perlucidalis Hübner. Eén exemplaar te Ouddorp op 12.VI.1964. 5. Agdistis statuts Millière. Eén exemplaar te Melissant op 24.VIII.1960. Summary Five Lepidoptera are mentioned, which were taken on the island of Goeree- Overflakkee (South Holland prov.) in the course of 1964. Porphyrinia parva is new to the Dutch fauna. Melissant, Plein 7. Late Spilosoma lubricipeda L. (Lep., Arctiidae). De laatste datum van de Tienuursvlinder was tot nog toe 14..X. In 1962 zag de heer van Aartsen er één op 16.X, maar een record is ongetwijfeld 22.X.1963. Op die datum zag ik in Amsterdam een mooi gaaf exemplaar tegen een boomstam zitten, een meter of drie van de grond -— Lpk. -

7 Days in the Netherlands by Bike

www.goodtravel.guide 7 Days in the Netherlands by bike More than windmills and tulips: beaches, islands, authentic villages and undiscovered green destinations You can find a complete map of the trip here: https://goo.gl/maps/XFzREV41BNVManhS6 Noordwijk Katwijk Hoek van Holland Westvoorne Goeree-Overflakkee Schouwen-Duiveland Veere 7 sustainable destinations recognized by Green Destinations and Quality Coast Award 7 days 12 hours o n a r o a d Difficulty: I n t e r m e d i a t e First stop, Amsterdam. The essential thing you need to have for this trip is a bike and necessary equipment. It’s great if you have your own old good one, otherwise, you can rent it. Some companies offer cycling packages including a road bike, helmet, repair kit, and a lock (for example, “I cycle Holland”). Before you start: remember to bring a reusable bottle and drink water regularly during your trip, prepare healthy snacks to keep you energized and make sure you have all the protective gear you need, as well as a GPS. You can find a complete map of the trip here: https://goo.gl/maps/XFzREV41BNVManhS6 You can also use this map of the official cycling lane network to plan your trip along well-signposted bike lanes and low-traffic roads: https://www.anwb.nl/fietsroutes/fietsknooppuntenplanner For almost all displacement of this guide you can use the Long-distance route LF1 along wonderful car-free cycle paths through the dunes (and cycle over the amazing Oosterschelde storm surge barrier). If starting from Amsterdam, you can head for De Zilk and then connect to LF1. -

Rotterdam & South Holland

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Rotterdam & South Holland Why Go? South Holland ................147 Think Holland and you’re thinking of the region southwest Leiden ............................147 of Amsterdam where tulips, cheese, Vermeer and plucky Den Haag (The Hague) ..153 Dutch people standing up to the sea avoid cliché simply by Gouda .............................161 their omnipresence. South Holland’s major cities are the biggest attractions. Delft............................... 163 Mighty Rotterdam is blessed with an edgy urban vibe, sur- Rotterdam ..................... 168 prising cultural scene and striking architecture. Leiden has Dordrecht ...................... 183 its university culture and old town (and proximity to the Biesbosch National bulbfields). Den Haag has museums, a stately air, luxe shop- Park ............................... 186 ping and a kitsch beach, while charming, beautiful Delft is Slot Loevestein ............. 186 a medieval time capsule. Smaller places are also worth your Zeeland ......................... 186 time: Gouda is a perfect old canal town, while Dordrecht Middelburg .....................187 has its own surprises amid canals and charm. Waterland Neeltje Jans .191 Further south, Zeeland (Sea Land) is the dyke-protected Schouwen-Duiveland.....191 province that people often associate with the Netherlands when they’re not thinking of tulips and windmills. Cycling Zeeuws-Vlaanderen .......192 in this flat, mostly sub-sea-level region is unparalleled. Best Places to Eat When to Go » De Dames Proeverij (p 151 ) The heart of Holland can be enjoyed year-round. Rotter- » Spijshuis de Dis (p 167 ) dam is full of museums and nightlife, so you can ignore the » Z&M (p 177 ) weather while indoors. The same can be said to a certain ex- » De Ballentent (p 177 ) tent for the main towns and cities such as Leiden, Den Haag » De Stroper (p 185 ) and Delft. -

Internal Migration and Regional Population Dynamics in Europe: Netherlands Case Study

This is a repository copy of Internal Migration and Regional Population Dynamics in Europe: Netherlands Case Study. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/5035/ Monograph: Rees, P., van Imhoff, E., Durham, H. et al. (2 more authors) (1998) Internal Migration and Regional Population Dynamics in Europe: Netherlands Case Study. Working Paper. School of Geography , University of Leeds. School of Geography Working Paper 98/06 Reuse See Attached Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ WORKING PAPER 98/06 INTERNAL MIGRATION AND REGIONAL POPULATION DYNAMICS IN EUROPE: NETHERLANDS CASE STUDY Philip Rees1 Evert van Imhoff2 Helen Durham1 Marek Kupiszewski1,3 Darren Smith1 August 1998 1School of Geography University of Leeds Leeds LS2 9JT United Kingdom 2Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute Lange Houtstraat 19 2511 CV The Hague The Netherlands 3Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization Polish Academy of Sciences Twarda 51/55 Warsaw Poland Report prepared for the Council of Europe (Directorate of Social and Economic Affairs, Population and Migration Division) and for the European Commission (Directorate General V, Employment, Industrial Relations and Social Affairs, Unit E1, Analysis and Research on the Social Situation) ii CONTENTS Abstract Foreword Terms of reference Acknowledgements List of tables List of figures 1. CONTEXT 2. INTERNAL MIGRATION AND POPULATION CHANGE REVIEWED 2.1 The national population and migration context 2.2 Regional shifts 2.3 Provincial changes 2.4 Redistribution between settlement types 2.5 Age group patterns 3. -

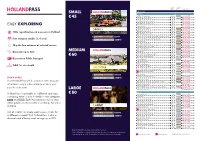

Easy Exploring Large € 80 Medium € 60 Small € 45

regular use for free price entry or get discount SMALL AMSTERDAM ATTRACTIONS € 45 LOVERS - 1hr Canal Cruise € 16,00 20% DISCOUNT LOVERS Semi-Open Boat Cruise € 16,00 20% DISCOUNT Amsterdam Burger or Pizza Cruise € 42,50 20% DISCOUNT EASY EXPLORING Amsterdam Luxurious Dinner Cruise € 92,50 20% DISCOUNT Candlelight Cruise € 42,50 20% DISCOUNT Canal Cruise Weesp Muiden € 22,50 20% DISCOUNT 100+ top attractions & museums in Holland KINBOAT Cruise Like a Local € 24,50 20% DISCOUNT KINBOAT Small Open Boat Tour € 16,00 20% DISCOUNT 1 GOLD FREE ENTRANCE CREDIT Hop On-Hop Off City Sightseeing Amsterdam - By bus & boat 24hrs € 39,00 20% DISCOUNT Free entrance credits (3, 4 or 6) Hop On-Hop Off City Sightseeing - By boat 24hrs € 27,50 20% DISCOUNT 2 SILVER FREE ENTRANCE CREDITS Amsterdam Icebar € 23,95 20% DISCOUNT Amsterdam Castle Muiderslot € 15,50 20% DISCOUNT Skip the line entrance at selected venues Amsterdam Nightlife Ticket - 2 days € 10,00 20% DISCOUNT ARTIS Amsterdam Royal Zoo € 24,00 10% DISCOUNT Discounts up to 50% MEDIUM ARTIS-Micropia € 16,00 10% DISCOUNT € 60 BODY WORLDS: The Happiness Project € 23,95 20% DISCOUNT Boom Chicago Live Comedy Show € 21,95 25% DISCOUNT Discount on Public Transport Discover Rembrandt € 15,00 GASSAN Dam Square - 5% DISCOUNT Heineken Experience € 21,00 20% DISCOUNT Valid for one month Hortus Botanicus Amsterdam € 9,75 20% DISCOUNT House of Bols Cocktail & Genever Experience Ticket € 16,00 10% DISCOUNT Madame Tussauds Amsterdam € 24,50 20% DISCOUNT 2 GOLD FREE ENTRANCE CREDITS Molen van Sloten € 8,50 Museumfoto: Become the art you see! € 14,50 30% DISCOUNT How it works? 2 SILVER FREE ENTRANCE CREDITS The Amsterdam Dungeon € 24,00 20% DISCOUNT Your Holland Pass will be scanned at the museum/ Ripley’s Believe it or Not! ‘Welcome to the world of weird’ € 21,50 10% DISCOUNT attraction to enjoy a free entrance or show your Royal Coster Diamonds tour - FREE OF CHARGE pass for a discount. -

Regions and Cities at a Glance 2020

Regions and Cities at a Glance 2020 provides a comprehensive assessment of how regions and cities across the OECD are progressing in a number of aspects connected to economic development, health, well-being and net zero-carbon transition. In the light of the health crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the report analyses outcomes and drivers of social, economic and environmental resilience. Consult the full publication here. OECD REGIONS AND CITIES AT A GLANCE - COUNTRY NOTE NETHERLANDS A. Resilient regional societies B. Regional economic disparities and trends in productivity C. Well-being in regions D. Industrial transition in regions E. Transitioning to clean energy in regions F. Metropolitan trends in growth and sustainability The data in this note reflect different subnational geographic levels in OECD countries: • Regions are classified on two territorial levels reflecting the administrative organisation of countries: large regions (TL2) and small regions (TL3). Small regions are classified according to their access to metropolitan areas (see https://doi.org/10.1787/b902cc00-en). • Functional urban areas consists of cities – defined as densely populated local units with at least 50 000 inhabitants – and adjacent local units connected to the city (commuting zones) in terms of commuting flows (see https://doi.org/10.1787/d58cb34d-en). Metropolitan areas refer to functional urban areas above 250 000 inhabitants. Regions and Cities at a Glance 2020 Austria country note 2 A. Resilient regional societies Cities have 11-percentage points higher share of jobs amenable to remote working than rural areas in the Netherlands. A1. Share of jobs amenable to remote working, 2018 by degree of urbanisation Cities Towns and semi-dense areas Rural areas % 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 The share of jobs that are amenable to remote working in the Netherlands ranges from 44% in cities to 33% in rural areas. -

Choose Your Package Large € 80 Medium € 60 Small € 45

GOLD/ YOU SILVER SAVE AT THE DOOR SMALL AMSTERDAM CITY CENTRE ATTRACTIONS € 45 LOVERS - 1HR CANAL CRUISE € 18,00 20% DISCOUNT LOVERS Semi-open Boat Cruise € 18,00 20% DISCOUNT Amsterdam Pizza & Burger Cruise € 42,50 20% DISCOUNT CHOOSE YOUR PACKAGE Amsterdam Luxurious dinner Cruise € 92,50 20% DISCOUNT Candlelight Cruise € 42,50 20% DISCOUNT KINBOAT Cruise Like a Local € 24,50 20% DISCOUNT Each museum/attraction accepts either golden KINBOAT Small Open Boat tour € 18,00 20% DISCOUNT or silver credits in exchange for a free entrance. Hop On-Hop Off City Sightseeing Amsterdam - by bus & boat 24hrs € 39,00 20% DISCOUNT 1 GOLD FREE ENTRANCE CREDIT Hop On-Hop Off City Sightseeing - By boat 24hrs € 27,50 20% DISCOUNT In this overview and at hollandpass.com you can 2 SILVER FREE ENTRANCE CREDITS BODY WORLDS: The Happiness Project € 23,95 20% DISCOUNT check out which museums and attractions are Amsterdam Icebar € 23,95 20% DISCOUNT included in the and categories. Ripley’s Believe it or not! ‘Welcome to the world of weird’ € 21,50 10% DISCOUNT Madame Tussauds Amsterdam € 21,00 20% DISCOUNT MEDIUM Museumfoto: Become the art you see! € 14,50 30% DISCOUNT Out of credits? Or simply want to save credits for The Amsterdam Dungeon € 20,50 20% DISCOUNT a different moment? Your Holland Pass is also a € 60 Boom Chicago Live Comedy Show € 21,95 25% DISCOUNT A FREE BRILLIANT discount card offering smart savings up to 50% TOUR Gassan Diamonds - GIFT at museums, attractions, excursions, restaurants GASSAN Dam Square - 5% DISCOUNT MUSEUMS and shops. -

Netherlands Successes Bus Rail Case Study

Ferrol A Coruña Lugo Aalborg Santiago Orense Cross border service to Holstebro Norway Stockholm Alcorcón Madrid Copenhagen Esbjerg Alcudia Roskilde Palma Helsingborg Cross border service to Germany 44/45 Braga Udine Como Lecco How we work Arriva Mainland Europe Trieste Guimarães Netherlands SuccessesBergamo Brescia Groningen Milan Porto Leeuwarden Cremona • In DecemberTurin 2012 Arriva successfully mobilised two Cross border service major regional bus contracts within the Friesland and to Germany South Holland North regions. Imperia • Arriva is the best performing rail operator in the Netherlands. Our latest average punctuality rating is Amsterdam Arnhem 97 per cent. Rome • The Ministry for Transport commissioned a survey Lisbon ‘s-Hertogenbosch of 90,000 public transport users, with Arriva Almada ranking highest for bus. Bus and rail had an average Setubal satisfaction rating of 7.4 out of 10. • Arriva has worked in partnership with the national Bus government to introduce the OV-Chipkaart, a national smartcard for integrated public transport Rail use throughout the Netherlands. It is also trialling Waterbus Touch&Travel – an app which allows passengers to check on and off public transport, regardless of the provider, route or mode, using their smartphone. The app also calculates transport use and passengers pay Key dates at the end of the month by direct debit. Victoria • Integrated transport is a key feature of transport in the Teplic2012e Started operating South Holland North Bus Rail Svoboda Netherlands. Arriva successfully operates a number Mladá Boleslavand Friesland bus contracts Liberalisation stage: mature Liberalisation stage: mid-liberalisation nad Úpou of integrated transport contracts, including that for 2012 The Vechtdallijnen 15-year rail Achterhoek-Rivierenland.