Bracha Hasmucha Lechaverta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meshech Chochmah

Rabbi Immanuel Bernstein 2019 / 5779 MESHECH CHOCHMAH Parshas Bechukosai Miracles and Nature םאִ בְ ּחֻקֹּתַי תֵ ּלֵכּו... וְ נָתַתִ ּי גִשְׁמֵ יכֶם בְּעִתָ ּם If you will follow My decrees …I will provide your rains in their time (26:3-4) Our parsha opens with the Torah’s promises of blessings if the Jewish people fulfil its mitzvos. We note that the Torah does not say that if we fulfil the mitzvos then Hashem will perform miracles for us. Rather, the blessings are expressed within the bounds of nature, such as rains in their time. This teaches us a profound lesson regarding the way in which Hashem wishes to bestow His blessing on the world. Although there are times when Hashem has performed miracles for the Jewish people, these do not represent the ideal way that He wishes to run the world. Rather, it is the rules of nature, ordained by Hashem, that contain within them the capacity to provide for the needs of all life-forms. If the Jewish people follow the Torah, then the medium of nature will be maximized to produce plenty and fulfil all their needs. THE ROLE OF MIRACLES A direct corollary of this idea is the crucial recognition that the laws of nature are not programed in advance to produce a set amount depending on natural input alone. Rather they are constantly being governed by Divine supervision in response to the spiritual level of the Jewish people, based on which Hashem will decide how much blessing to bestow within those laws. Thus, the midrash states1 that in the generation of R’ Shimon ben Shatach – one in which people were extremely righteous – the rains fell consistently on Friday nights, a time when people are at home and no inconvenience was caused by the rain. -

Amen, Until the Final Breath

בס"ד PARASHAS VAYIKRA IN THE PATHWAYS OF FAITH Divrei Torah About Amen and Tefillah in the Parashah One Who Refrains from Davening with mitzvah off netilasnetilas yadayim, washing ones hands, Teshuvah for Individuals and the Klal a Tzibbur is Punished Measure for Measure which can atone ffor the “ani bedaas, the poor man ”אם הכהן המשיח יחטא לאשמת העם“ (ד, ג) in wisdom” as a Minchah. An allusion to this can be found in the words of the brachah: “al netilas The Avodas Hagershuni, a commentary on Shir ”אדם כי יקריב מכם קרבן לה‘“ (שם) In his sefer Derech Moshe (Day 9) the early yadayim is an acronym for “ani”, a poor man. Hashirim (3,4) brings a beautiful allusion in this mochiach Rabbi Moshe Kahana of Gibitisch Chochmas Shlomo, Orach Chaim 158 1 passuk in the name of his father Rabi Avraham, relates: the brother of the Vilna Gaon: In Maseches I once came to a town and stayed at the home of Avodah Zarah (4b) Chazal said that because of the parnas of the city, who was also a shochet. A Truly Perfect Korban their elevated status, Bnei Yisrael really should not .have transgressed with the sin of the cheit ha’egel ”דבר אל בני ישראל ואמרת אלהם אדם כי יקריב מכם When I rose in the morning and wanted to go They did so only so that future generations should קרבן לה‘“ (ב, ב) out to daven with the minyan in shul, I saw him busy slaughtering an animal. When he finished, I The Sifsei Kohein al HaTorah says: “Mikem” learn that many who sin together can repent. -

The Roadmap to Prayer Lesson 2

THE PIRCHEI SHOSHANIM ROADMAP TO PRAYER PROJECT The Roadmap to Prayer Lesson 2 Pirchei Shoshanim 2005 This shiur may not be reproduced in any form without permission of the copyright holder Rehov Beit Vegan 99, Yerushalayim 03.616.6340 164 Village Path, Lakewood NJ 08701 732.370.3344 fax 1.877.Pirchei (732.367.8168) THE PIRCHEI SHOSHANIM ROADMAP TO PRAYER PROJECT AN ATTACHMENT OF THE SOUL Lesson The Roadmap 2 To Prayer The Four Spiritual Spheres Atzilus Briyah Yetzirah Assiyah There are four spiritual worlds that represent four levels in creation. They are: Y Atzilus – The world of G-d’s thought Y Briyah – The world of creation Y Yetzirah – The world of formation Y Assiyah – The world of integration These terms are generally used in esoteric writings of Kabalah. We use it here to represent the lofty ideals of Prayer; as we ascend with it to spiritual heights. After all, we do actually Pray to G-d directly. The Highest level being Atzilus and the lowest level Assiyah that corresponds to the world we live in. The Daily Prayer: Ascending the Spiritual The Men of the Great Assembly (Anshei Knesses Hagedolah) which consisted of 120 Realms of PROPHETS and Sages arranged our daily prayers (tefilas) to correspond to these Asiyyah, Yetzirah, Briyah and Atzilus through Prayer four spiritual spheres. These men fixed the text of the daily prayer (Shemoneh Esrei- the “Eighteen Benedictions”). From that point and onward in became incumbent upon every Jew to pray three times daily. We then systematically work our way up from one level to the next until we reach the highest sphere Atzilus. -

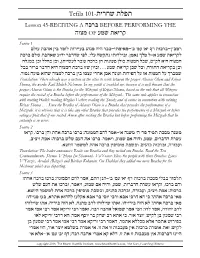

Lesson Fifty-One-Reciting a Bracha

Tefila 101- Lesson 45-RECITING A BEFORE PERFORMING THE OF Source 1 Translation: There already was a custom in the cities to recite between the prayer Ahavas Olam and Kriyas Shema, the words: Kail Melech Ne’eman. In my youth it troubled me, because it is well known that the prayer Ahavas Olam is the Bracha for the Mitzvah of Kriyas Shema, based on the rule that all Mitzvos require the recital of a Bracha before the performance of the Mitzvah.. The same rule applies in connection with reciting Hallel; reading Megilas Esther; reading the Torah; and of course in connection with reciting Kriyas Shema . Since the Bracha of Ahavas Olam is a Bracha that precedes the performance of a Mitzvah, it is obvious that it is like any other Bracha that precedes the performance of a Mitzvah or before eating a fruit that if one recited Amen after reciting the Bracha but before performing the Mitzvah that he certainly is in error. Source 2 Translation: The leader announces: Recite one Bracha and they recited one Bracha. Read the Ten Commandments, Shema, V’Haya Im Shamoah, Va’Yomer. Bless the people with three Brachos: Emes V’Yatziv, Avodah (Ritzai) and Birchas Kohanim. On Shabbat they added one more Bracha for the Mishmar which was departing. Source 3 copyright 2018. The Beurei Hatefila Institute, www.beureihatefila.com, Abe Katz, Founding Director Tefila 101- Translation: We have learnt elsewhere: The supervising Kohain called out: Recite one Bracha, and they said one Bracha and then recited the Ten Commandments, the Shema’, the section “Va’Yomer” and recited with the people three Brachos: Emes V’Yatziv, Avodah and Birkas Kohanim. -

TEMPLE ISRAEL of the POCONOS Edition 608 Temple Israel of The

Page TEMPLE ISRAEL OF THE POCONOS Edition 608 Temple Israel of the Drawing by Marilyn Margolies Poconos May 2015 Iyar/Sivan 5775 Edition 608 A monthly publication of Temple Israel of the Poconos Inside this Issue CREATOR OF DARKNESS Rabbi’s Message 1 President’s Message 3 by Rabbi Baruch Binyamin Hakohen Melman Norman Gelber 4 Concert 6 Hebrew School 7 Ask the Rabbi 8 Holiday Page 10 Scientists have recently discovered that 95% of the cosmos is made up of Dark Word Search 12 Matter (25%)and Dark Energy (70%). The other 5% is what we had always thought of Save the Date 13 as the principal "stuff" of the universe - i.e. the stars, the galaxies, the planets and Donations 14 the stardust from whence we all come. What does this mean? It means that dark- Chessed 15 ness is not merely the absence of light! There is an actual invisible substance that is Birthdays/ inherently dark in its own right, irrespective of the presence or absence of a light Anniversaries 16 source. We only know that it is there because of gravity. We cannot see it directly, Yahrzeit Lists 17/18 but we can see the distortion of light caused by its gravitational pull. Calendar 19 Advertising 23 At the start of the Shacharit Service following the public call to prayer (the Barchu), we say "Baruch...Yotzer ohr uVorey Choshech, Oseh Shalom uVoreh et aKawl." "Blessed are You... Sovereign of the Universe, who forms light and CREATES DARKNESS, makes peace and creates everything (including evil)." Darkness is therefore created, and is not merely the absence of light. -

Jewish Religious Observance by the Jews of Kaifeng China

1 Jewish Religious Observance by the Jews of Kaifeng China by Rabbi Dr. Chaim Simons Kiryat Arba, Israel June 2010 2 address of author P.O. Box 1775 Kiryat Arba, Israel telephone no. 972 2 9961252 e-mail: [email protected] © Copyright. Chaim Simons. 2010 3 Acknowledgements are due to the following: Librarians and Staff of the following libraries: The Jewish National and University Library, (including microfilms department), Jerusalem Mount Scopus Library, Jerusalem Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design Library, Jerusalem Bar-Ilan University Library, Ramat Gan Kiryat Arba Municipal Library Yeshivat Nir Library, Kiryat Arba Chasdei Avot Synagogue Library, Kiryat Arba Hebrew Union College Libraries, Jerusalem, New York and Cincinnati Internet: Hebrew Books Google Books National Yiddish Book Center, Amhurst, Massachusetts Various authors of material Wikipedia Users of Wikipedia Reference Desk who answered the author‟s questions Miscellaneous: Otzar Hachochma Rabbi Eliyahu Ben-Pinchas, Kiryat Arba Rabbi Yisrael Hirshenzon, Kiryat Arba Rabbi Baruch Kochav, Kiryat Arba Rabbi Mishael Rubin, Kiryat Arba 4 CONTENTS Section 1: PRELIMINARY INFORMATION …………………………….. 5 Transliterations………………………………………………………………….. 6 Glossary of Hebrew and Yiddish Words………………………………………. 6 Abbreviations appearing in footnotes………………………………………….. 13 Guide to books and manuscripts appearing in footnotes………………………. 13 Section 2: INTRODUCTION………………………………………………… 28 What this Book includes………………………………………………………… 29 What this Book does not include………………………………………………... 29 A very brief synopsis of the history of the Jews of Kaifeng……………………. 30 A very brief historical synopsis of the sources for Jewish Law………………… 33 Sources of Information on Mitzvah Observance by the Kaifeng Jews…………. 34 Section 3: MITZVAH OBSERVANCE IN KAIFENG……………………… 41 Tzitzit……………………………………………………………………………. 42 Tefillin…………………………………………………………………………… 45 Mezuzah…………………………………………………………………………. 46 Tefillah…………………………………………………………………………… 47 Reading the Torah………………………………………………………………. -

Dltzd Z` Oiadl

dltzd z` oiadl A Look At the Sources and Structure of the Prayers in the xeciq Part 11 zayl sqene zixgy zltz TABLE OF CONTENTS Copyright 2012. Compiled and Edited by Abe Katz dltzd z` oiadl Table of Contents Volume Number: 11 Newsletter Number: Page Number 7-2 INTRODUCTION TO dxnfc iweqt OF zixgy zltz ON zay. 5 SUPPLEMENT: SOURCES THAT CONCERN dxyr dpeny sqen OF dpyd y`x . 11 7-3 MODIFYING THE WORDS OF xn`y jexa ON zay . 14 7-4 xiyd zltz. 18 SUPPLEMENT: INTRODUCTION TO zepryed FOUND IN THE milaewne mipe`bd xeciq . 22 7-5 THE PRAYERS THAT PRECEDE xn`y jexa ON zay. .. .. 25 7-6 INTRODUCTION TO ig lk znyp . 29 7-7 IS ig lk znyp A SINGLE heit OR A COMBINATION OF miheit . 33 7-8 MODELS OF JEWISH PRAYER . 37 7-9 THE LINES THAT FOLLOW cr okey . 45 SUPPLEMENT: DID THE APOSTLE PETER COMPOSE ig lk znyp . 49 7-10 INTRODUCTION TO THE rny z`ixw zekxa OF zixgy zay . 54 7-11 RECITING miheit WITHIN THE zekxa OF rny z`ixw . 60 SUPPLEMENT: RUTH LANGER’S CONCLUSION TO HER ARTICLE: THE LANGUAGE OF PRAYER: THE CHALLENGE OF PIYUT . 66 7-12 ARE THE miheit OF jecei lkd AND oec` l-` LINKED TO xveic dyecw . 68 7-13 jecei lkd . 72 SUPPLEMENT: AN IMPORTANT DIFFERENCE BETWEEN laa bdpn AND l`xyi ux` bdpn . 77 7-14 oec` l-` . .78 7-15 zay xy` l-`l . 83 7-16 THE LINK BETWEEN zay xy` l-` AND dad`a minrt . -

Makkas Bechoros: Firstborn Vengeance R’ Chaim Soskil

למען תספר A Journal of Divrei Torah in honor of Pesach 5781 Compiled by the Members of the Bais Medrash of Ranchleigh 6618 Deancroft Rd Baltimore, MD 21209 No rights reserved Make as many copies as you like For your convenience, this Kuntress along with other Torah works and Shiurim associated with the Zichron Yaakov Eliyahu Fund are available online for free download at www.zichronyaakoveliyahu.org It was on Erev Shabbos, Zos Chanukah when the Mara D’Asra offered me the privilege of sponsoring this year’s Pesach Kuntress. At that point, Pesach was the furthest thing from my mind. There were still several sufganiyot to eat, latkes to digest, and challah to buy – not exactly very Pesach-like. But, perhaps, upon closer reflection, there indeed, may be a connection between the two. U’Lemaan Tesapeir b’aznei bincha u’ben bincha. Why does the pasuk require us to give the message davka, “b’aznei bincha,” in the ears of the children? The Tolner Rebbe, shlita, explains that when you give a message into a listener’s ear, it means that the message and intent is specifically crafted and delivered for that person. On Seder night, when the transmission of our mesorah is in the line, it does not suffice to provide a generic, blanket declaration. Rather, father and grandfather, Rebbi and Morah, are required to craft a message that is fit, appreciated, and understood by the individual listener. Each generation, each era, and each child needs a uniquely developed message that will resonate b’aznei bincha. Since last Pesach, the messages and words we imparted to our children were Corona, quarantine, bidood, vaccination, and social distancing. -

Newsletter Vol

dltzd z` oiadl Vol. 7 No. 2 r"yz dpyd y`x zay INTRODUCTION TO dxnfc iweqt OF zixgy zltz ON zay zixgy zltz for zay is longer than the daily zixgy zltz primarily because we recite a larger number of dxnfc iweqt. The only change we make before dxnfc iweqt is to recall the additional zepaxw of zay. A question arises concerning the additional dxnfc iweqt. Which set of dxnfc iweqt developed first; the longer version which was shortened to accommodate the needs of daily life or the shorter version which was extended for zay? Rabbi Zeligman Baer in his l`xyi zcear xeciq provides two comments on the difference between dxnfc iweqt on zay and the weekday: ,ea lkd oeyl dfe ,legd on elicadle zayd ceakl zegaya miaxn zaya-gvpnl dpezpd dxezd on mixacn md yie dxivia mixacn mda yi mixenfn zaya oitiqen oyi yexitae .epeyl o`k cr zaya enk aeh meia oze` mixne` miaeh mini ceakle ,zaya meil xiy xenfn caln mlek mixenfn mze` xnel epl did lega s`y `ed oica ik iz`vn bdpn iepiy yi elld mixenfna dpde .lega mxn`l erpnp xeaivd gxeh iptn j` ,zayd mixecqy enke ezepya cecl mcew miwicv eppx mixne` micxtqde micxtqde mifpky`d oia zyng z` 'd ziaa micnery d-ielld oiae xzqa ayei oia mitiqen cere `xwna .c"kwe ,b"kwe ,a"kwe ,`"kwe ,g"v onq mixenfnd Translation: On Shabbos we increase the amount of praise we heap on G-d in order to honor Shabbos and to distinguish Shabbos from the weekdays. The Kol Bo describes the additional chapters of Tehillim as follows: “we recite additional chapters of Tehillim on Shabbos. -

BULLETIN Los Angeles, CA 90035

ADAS TORAH Rabbi Dovid Revah 9040 W Pico Blvd. BULLETIN Los Angeles, CA 90035 פרשת וארא ג׳ שבט תשפ״א • January 16th 2021 take place in the main Shul, Simcha Hall, and the front SHUL courtyard. SHABBOS SCHEDULE Motzei Shabbos learning this ANNOUNCEMENTS week is sponsored by Michael Shelli Borkow in celebration & הדלקת נרות Candle Lighting 4:49 pm MAZAL TOV of Binyamin Moshe receiving מנחה Mincha - Fri 4:55 pm Shacharis 7:30/8:00/8:50/9:15 am Mazal Tov to Shayna & his first Siddur and Chumash. Shoshana Kleinman on their Please speak to Rabbi Revah if מנחה Mincha - Shab 4:40 pm Bas Mitzvah! Mazal Tov to you would like to sponsor. .Tomer & Jamie Kleinman מעריב Maariv 5:50 pm All adults and children must Mazal Tov to Evan Silver wear masks the whole time SHABBOS ZMANIM for being the first person in during Motzei Shabbos our Yoreh Deah Chabura to learning, even when sitting in complete all the tests. We wish their seats. שקיעה Shkiyah - Fri 5:07 pm him continued hatzlacha in his DAF YOMI/SHACHARIS עלות השחר Alos Hashachar 5:41 am limud HaTorah! Rabbi Simcha Bornstein gives זמן ציצית Tzitzis 6:10 am SHABBOS a 6:00 am Daf Yomi Shiur via הנץ החמה Sunrise 6:59 am .Thank you to the Aharon Zoom סוף זמן ק’’ש–מ׳’א L/T for Shema 8:51 am family for driving Tomchei this Rabbi Revah gives a Mishnah סוף זמן ק’’ש L/T for Shema 9:31 am week. Please click here for the Berura Shiur daily from 7:30 am סוף זמן תפילה L/T for Tefilah 10:21 am new Tomchei Shabbos sign up - 7:45 am live and on Zoom. -

The Practical Parameters of Prayer

Panu Derekh Journal - Prepare The Way :rC¦S "v hP hF uº¨S§j³h r«¨aCkf Ut¨r±u "v sIcF vk±d°b±u The Practical Parameters of Prayer What Everyone Needs To Know Sephardic Halakha (Jewish Law) & Kabbalistic Insights (With A Word for the Benei Noah) By Rabbi Ariel Bar Tzadok Introduction All of us pray in one sort of fashion or The Sephardic tradition is quite more another. Yet, I am well aware that not lenient. The Rishon L’Tzion Rabbi Ovadiah everyone can be a Kabbalist and pray as I Yosef writes1 that in fact a woman is have outlined here. Nonetheless, we have required by law to pray only once a day. our obligations and these need to be They may pray all three prayers daily if they addressed in light of how most people are so choose. Yet, they are not required to do living today in the modern world. so. Every male Jew above the age of Bar Another great Sephardic Sage, Rabbi Ben Mitzvah (13) is required to daily recite the Tzion Abba Shaul has written that women three prayer services. Yet, the order of are required to pray the morning and Kabbalistic kavanot is obviously geared afternoon services but not the evening towards those Jewish men who have the service. time and ability to learn them and use them in prayer. Obviously this leaves out many of Most Sephardic women follow the view of us. So, what are we to do when we are in a Rabbi Ovadiah Yosef. Now that we have rush and don’t have time to perform the reviewed obligation, let us review prayer by kavanot? Many men are so rushed on choice. -

Packet #19 Kabolas Shabbos

ב״ה TEFILLAH PACKET #19 Kabolas Shabbos In Kabolas Shabbos on Friday night, we start off with six kapitelach of Tehillim. These correspond to the six days of the week. The last one, “Mizmor LeDovid, Havu LaHashem,” is the one that corresponds to Friday. After this, we say the paragraph of Ana Bekoach, which has 42 words. The first letters of all of these words together spell one of the names of Hashem! Now that we have mentioned each of the six days of the week, we say Lecha Dodi. This, and the rest of davening, is to honor the holy day of Shabbos! Vayechulu After Shemoneh Esrei on Friday night, we say a paragraph called Vayechulu. We usually say this paragraph together with the minyan. After Vayechulu, the chazan says a special bracha called the Bracha Me’ein Sheva. We say the middle paragraph of this bracha together with the chazan. It is important to be part of the minyan and have kavana when we say these parts of davening! In Shulchan Aruch, there is a story: A chossid had a dream about another chossid. In the dream, his friend’s face was turning green! He asked his friend, “Why is your face turning green?” The chossid answered, “On Friday night, when the chazan was saying Vayechulu, I didn’t say it with him. I also used to talk when the chazan said the Bracha Me’ein Sheva. I didn’t even pay attention when he was saying Kaddish afterwards. That’s why my face is turning green.” The Shulchan Aruch finishes off by saying that you should be careful to participate with the minyan during these parts of davening Friday night! (See the Alter Rebbe’s Shulchan Aruch, Siman Reish-Samach- Ches se’if yud-zayin) Praising Hashem on Shabbos Every single day, we praise Hashem in davening.