Makkas Bechoros: Firstborn Vengeance R’ Chaim Soskil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wedding Customs „ All Piskei Horav Yisroel Belsky Shlita Are Reviewed by Horav Yisroel Belsky Shlita

Halachically Speaking Volume 4 l Issue 12 „ Compiled by Rabbi Moishe Dovid Lebovits „ Reviewed by Rabbi Benzion Schiffenbauer Shlita Wedding Customs „ All Piskei Horav Yisroel Belsky Shlita are reviewed by Horav Yisroel Belsky Shlita Lag B'omer will be upon us very soon, and for this is because the moon starts getting people have not been at weddings for a while. smaller and it is not a good simon for the Therefore now is a good time to discuss some chosson and kallah.4 Others are not so convinced of the customs which lead up to the wedding that there is a concern and maintain one may and the wedding itself. marry at the end of the month as well.5 Some are only lenient if the chosson is twenty years of When one attends a wedding he sees many age.6 The custom of many is not to be customs which are done.1 For example, concerned about this and marry even at the walking down the aisle with candles, ashes on end of the month.7 Some say even according to the forehead, breaking the plate, and the glass, the stringent opinion one may marry until the the chosson does not have any knots on his twenty-second day of the Hebrew month.8 clothing etc. Long Engagement 4 Chazzon Yeshaya page 139, see Shar Yissochor mamer When an engaged couple decide when they ha’yarchim 2:pages 1-2. 5 Refer to Pischei Teshuva E.H. 64:5, Yehuda Yaleh 2:24, should marry, the wedding date should not be Tirosh V’yitzor 111, Hisoreros Teshuva 1:159, Teshuva 2 too long after their engagement. -

Seudas Bris Milah

Volume 12 Issue 2 TOPIC Seudas Bris Milah SPONSORED BY: KOF-K KOSHER SUPERVISION Compiled by Rabbi Moishe Dovid Lebovits Reviewed by Rabbi Benzion Schiffenbauer Shlita Edited by: Rabbi Chanoch Levi HALACHICALLY SPEAKING Halachically Speaking is a Proofreading: Mrs. EM Sonenblick monthly publication compiled by Rabbi Moishe Dovid Lebovits, Website Management and Emails: a former chaver kollel of Yeshiva Heshy Blaustein Torah Vodaath and a musmach of Harav Yisroel Belsky Shlita. Rabbi Dedicated in honor of the first yartzeit of Lebovits currently works as the Rabbinical Administrator for ר' שלמה בן פנחס ע"ה the KOF-K Kosher Supervision. SPONSORED: Each issue reviews a different area of contemporary halacha לז"נ מרת רחל בת אליעזר ע"ה with an emphasis on practical applications of the principles SPONSORED: discussed. Significant time is spent ensuring the inclusion of לרפואה שלמה ,all relevant shittos on each topic חיים צבי בן אסתר as well as the psak of Harav Yisroel Belsky, Shlita on current SPONSORED: issues. לעילוי נשמת WHERE TO SEE HALACHICALLY SPEAKING מרת בריינדל חנה ע"ה Halachically Speaking is בת ר' חיים אריה יבלח"ט .distributed to many shuls גערשטנער It can be seen in Flatbush, Lakewood, Five Towns, Far SPONSORED: Rockaway, and Queens, The ,Flatbush Jewish Journal לרפואה שלמה להרה"ג baltimorejewishlife.com, The רב חיים ישראל בן חנה צירל Jewish Home, chazaq.org, and frumtoronto.com. It is sent via email to subscribers across the world. SUBSCRIBE To sponsor an issue please call FOR FREE 718-744-4360 and view archives @ © Copyright 2015 www.thehalacha.com by Halachically Speaking ח.( )ברכות Seudas Bris Milah בלבד.. -

Leah Johnson

Roman - iii LEAH JOHNSON Scholastic Press / New York i_328_9781338503265.indd 3 1/8/20 2:38 PM Roman - iv Text copyright © 2020 by Leah Johnson Photos © Shutterstock: i crown and throughout (Anne Punch), i background and throughout (InnaPoka), 1 background and throughout (alexdndz), 31 icons and throughout (marysuper studio), 55, 180 emojis (Rawpixel . com). All rights reserved. Published by Scholastic Press, an imprint of Scholastic Inc., Publishers since 1920. scholastic, scholastic press, and associated log os are trademarks and/or registered trademarks of Scholastic Inc. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third- party websites or their content. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other wise, without written permission of the publisher. For information regarding permission, write to Scholastic Inc., Attention: Permissions Department, 557 Broadway, New York, NY 10012. This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data available ISBN 978-1-338-50326-5 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 20 21 22 23 24 Printed in the U.S.A. 23 First edition, June 2020 Book design by Stephanie Yang i_328_9781338503265.indd 4 1/8/20 2:38 PM one I’m clutching my tray with both hands, hoping that Beyoncé grants me the strength to make it to my usual lunch table without any incidents. -

A Taste of Jewish Law & the Laws of Blessings on Food

A Taste of Jewish Law & The Laws of Blessings on Food The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation A Taste of Jewish Law & The Laws of Blessings on Food (2003 Third Year Paper) Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:10018985 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA A ‘‘TASTE’’ OF JEWISH LAW -- THE LAWS OF BLESSINGS ON FOOD Jeremy Hershman Class of 2003 April 2003 Combined Course and Third Year Paper Abstract This paper is an in-depth treatment of the Jewish laws pertaining to blessings recited both before and after eating food. The rationale for the laws is discussed, and all the major topics relating to these blessings are covered. The issues addressed include the categorization of foods for the purpose of determining the proper blessing, the proper sequence of blessing recital, how long a blessing remains effective, and how to rectify mistakes in the observance of these laws. 1 Table of Contents I. Blessings -- Converting the Mundane into the Spiritual.... 5 II. Determining the Proper Blessing to Recite.......... 8 A. Introduction B. Bread vs. Other Grain Products 1. Introduction 2. Definition of Bread – Three Requirements a. Items Which Fail to Fulfill Third Requirement i. When Can These Items Achieve Bread Status? ii. Complications b. -

Welcoming New Alumni to Ner Michoel

Issue #13 • September 2016 • Elul 5776 הרב אדוננו רבי יצחק לוריא זכרונו לברכה כתב "ואשר לא צדה והאלקים 'אנה' 'לידו' 'ושמתי' 'לך'"... ראשי תיבות אלול, לומר כי חודש זה הוא עת רצון לקבל תשובה על החטאים שעשה בכל השנה .)קיצור שולחן ערוך סימן קכח'( he Arizal derives from the posuk which tells us that a Yisroel. You will read of Ner Michoel’s newest project in ,which talmidim are welcomed into the ranks of Ner Michoel ,עיר מקלט can save himself by taking refuge in an רוצח בשוגג Tthat there is a special time of year, Chodesh Elul, which as they take leave of the Yeshiva’s Beis Medrash. And of a special closeness, course, most importantly, you will read about “us” – the– רצון is a refuge of sorts. It is a time of during which teshuva is most readily accepted. alumni – two special individuals who have recently made the transition of resettling in the United States and another For us at Ner Michoel Headquarters this Arizal strikes a who recently celebrated a monumental accomplishment, a resonant chord, for as we write these words, we are presently Siyum HaShas. “taking refuge” in an aircraft above the Atlantic Ocean, en route to participate in an event marking the beginning of .גוט געבענשט יאר and a כתיבה וחתימה טובה Ner Michoel’s fifth year. Ner Michoel itself is meant to be Wishing everyone a an embassy, a refuge of sorts, through which our alumni can “touch back” to their years in Yeshiva. In this issue you will read of the various Ner Michoel events and projects, which concluded Year #4. -

Toronto to Have the Canadian Jewish News Area Canada Post Publication Agreement #40010684 Havdalah: 7:53 Delivered to Your Door Every Week

SALE FOR WINTER $1229 including 5 FREE hotel nights or $998* Air only. *subject to availabilit/change Call your travel agent or EL AL. 416-967-4222 60 Pages Wednesday, September 26, 2007 14 Tishrei, 5768 $1.00 This Week Arbour slammed by two groups National Education continues Accused of ‘failing to take a balanced approach’ in Mideast conflict to be hot topic in campaign. Page 3 ognizing legitimate humanitarian licly against the [UN] Human out publicly about Iran’s calls for By PAUL LUNGEN needs of the Palestinians, we regret Rights Council’s one-sided obses- genocide.” The opportunity was Rabbi Schild honoured for Staff Reporter Arbour’s repeated re- sion with slamming there, he continued, because photos 60 years of service Page 16 sort to a one-sided Israel. As a former published after the event showed Louise Arbour, the UN high com- narrative that denies judge, we urge her Arbour, wearing a hijab, sitting Bar mitzvah boy helps missioner for Human Rights, was Israelis their essential to adopt a balanced close to the Iranian president. Righteous Gentile. Page 41 slammed by two watchdog groups right to self-defence.” approach.” Ahmadinejad was in New York last week for failing to take a bal- Neuer also criti- Neuer was refer- this week to attend a UN confer- Heebonics anced approach to the Arab-Israeli cized Arbour, a former ring to Arbour’s par- ence. His visit prompted contro- conflict and for ignoring Iran’s long- Canadian Supreme ticipation in a hu- versy on a number of fronts. Co- standing call to genocide when she Court judge, for miss- man rights meeting lumbia University, for one, came in attended a human rights conference ing an opportunity to of the Non-Aligned for a fair share of criticism for invit- in Tehran earlier this month. -

Rabbi Eliezer Levin, ?"YT: Mussar Personified RABBI YOSEF C

il1lj:' .N1'lN1N1' invites you to join us in paying tribute to the memory of ,,,.. SAMUEL AND RENEE REICHMANN n·y Through their renowned benevolence and generosity they have nobly benefited the Torah community at large and have strengthened and sustained Yeshiva Yesodei Hatorah here in Toronto. Their legendary accomplishments have earned the respect and gratitude of all those whose lives they have touched. Special Honorees Rabbi Menachem Adler Mr. & Mrs. Menachem Wagner AVODASHAKODfSHAWARD MESORES A VOS AW ARD RESERVE YOUR AD IN OUR TRIBUTE DINNER JOURNAL Tribute Dinner to be held June 3, 1992 Diamond Page $50,000 Platinum Page $36, 000 Gold Page $25,000 Silver Page $18,000 Bronze Page $10,000 Parchment $ 5,000 Tribute Page $3,600 Half Page $500 Memoriam Page '$2,500 Quarter Page $250 Chai Page $1,800 Greeting $180 Full Page $1,000 Advertising Deadline is May 1. 1992 Mall or fax ad copy to: REICHMANN ENDOWMENT FUND FOR YYH 77 Glen Rush Boulevard, Toronto, Ontario M5N 2T8 (416) 787-1101 or Fax (416) 787-9044 GRATITUDE TO THE PAST + CONFIDENCE IN THE FUTURE THEIEWISH ()BSERVER THE JEWISH OBSERVER (ISSN) 0021 -6615 is published monthly except July and August by theAgudath Israel of America, 84 William Street, New York, N.Y. 10038. Second class postage paid in New York, N.Y. LESSONS IN AN ERA OF RAPID CHANGE Subscription $22.00 per year; two years, $36.00; three years, $48.00. Outside of the United States (US funds drawn on a US bank only) $1 O.00 6 surcharge per year. -

Moetzes Gedolei Hatorah of America

בס”ד STATEMENT OF THE MOETZES GEDOLEI HATORAH OF AMERICA קול קורא תנועת ‘אופען ארטאדאקסי’ )OPEN ORTHODOXY(, ומנהיגיה ומוסדותיה )ובכללם ‘ישיבת חובבי תורה’, ‘ישיבת מהר”ת’, ‘אינטרנשיונל רביניק פעלושיפ’ ועוד(, הראו פעמים בלי מספר שכופרים בעיקרי הדת והאמונה ובפרט בסמכותם של התורה וחכמיה. ובכן, אין הם שונים מכל יתר התנועות הזרות במשך הדורות שסרו מדרך התורה וכפרו בעיקריה ובמסורתה. לכן חובתנו להכריז דעתינו קבל עם שמכיון שהוציאה את עצמה מן הכלל, תנועה זו אינה חלק מיהדות התורה )הנקראת “ארטאדאקסי”(, ותואר “רב” )הנקרא בפיהם “סמיכה”( הניתן ע”י מוסדותיה אין לו שום תוקף. ואנו תפילה כי ירחם ה’ על שארית פליטתנו ויגדור פרצות עמנו, ונזכה לראות בהרמת קרן התורה וכבוד שמים. חשון תשע”ו מועצת גדולי התורה באמריקה PROCLAMATION “OPEN ORTHODOXY,” and its leaders and affiliated entities (including, but not limited to, Yeshivat Chovevei Torah, Yeshivat Maharat, and International Rabbinic Fellowship), have shown countless times that they reject the basic tenets of our faith, particularly the authority of the Torah and its Sages. Accordingly, they are no different than other dissident movements throughout our history that have rejected these basic tenets. We therefore inform the public that in our considered opinion, “Open Orthodoxy” is not a form of Torah Judaism (Orthodoxy), and that any rabbinic ordination (which they call “semicha”) granted by any of its affiliated entities to their graduates does not confer upon them any rabbinic authority. May the Almighty have mercy on the remnants of His people and repair all breaches in the walls of the Torah, and may we be worthy to witness the raising of the glory of Hashem and His sacred Torah. -

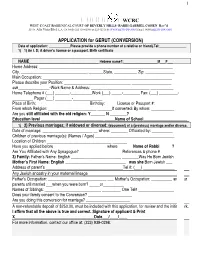

WCRC APPLICATION for GERUT (CONVERSION)

1 WCRC WEST COAST RABBINICAL COURT OF BEVERLY HILLS- RABBI GABRIEL COHEN Rav”d 331 N. Alta Vista Blvd . L.A. CA 90036 323 939-0298 Fax 323 933 3686 WWW.BETH-DIN.ORG Email: INFO@ BETH-DIN.ORG APPLICATION for GERUT (CONVERSION) Date of application: ____________Please provide a phone number of a relative or friend).Tel:_______________ 1) 1) An I. D; A driver’s license or a passport. Birth certificate NAME_______________________ ____________ Hebrew name?:___________________M___F___ Home Address: ________________________________________________________________ City, ________________________________ _______State, ___________ Zip: ______________ Main Occupation: ______________________________________________________________ Please describe your Position: ________________________________ ___________________ ss#_______________-Work Name & Address: ____________________________ ___________ Home Telephone # (___) _______-__________Work (___) _____-________ Fax: (___) _________- __________ Pager (___) ________-______________ Place of Birth: ______________________ ___Birthday:______License or Passport #: ________ From which Religion: _______________________ _______If converted: By whom: ___________ Are you still affiliated with the old religion: Y_______ N ________? Education level ______________________________ _____Name of School_____________________ 1) 2) Previous marriages; if widowed or divorced: (document) of a (previous) marriage and/or divorce. Date of marriage: ________________________ __ where: ________ Officiated by: __________ Children -

Whose History and by Whom: an Analysis of the History of Taiwan In

WHOSE HISTORY AND BY WHOM: AN ANALYSIS OF THE HISTORY OF TAIWAN IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE PUBLISHED IN THE POSTWAR ERA by LIN-MIAO LU (Under the Direction of Joel Taxel) ABSTRACT Guided by the tenet of sociology of school knowledge, this study examines 38 Taiwanese children’s trade books that share an overarching theme of the history of Taiwan published after World War II to uncover whether the seemingly innocent texts for children convey particular messages, perspectives, and ideologies selected, preserved, and perpetuated by particular groups of people at specific historical time periods. By adopting the concept of selective tradition and theories of ideology and hegemony along with the analytic strategies of constant comparative analysis and iconography, the written texts and visual images of the children’s literature are relationally analyzed to determine what aspects of the history and whose ideologies and perspectives were selected (or neglected) and distributed in the literary format. Central to this analysis is the investigation and analysis of the interrelations between literary content and the issue of power. Closely related to the discussion of ideological peculiarities, historians’ research on the development of Taiwanese historiography also is considered in order to examine and analyze whether the literary products fall into two paradigms: the Chinese-centric paradigm (Chinese-centricism) and the Taiwanese-centric paradigm (Taiwanese-centricism). Analysis suggests a power-and-knowledge nexus that reflects contemporary ruling groups’ control in the domain of children’s narratives in which subordinate groups’ perspectives are minimalized, whereas powerful groups’ assumptions and beliefs prevail and are perpetuated as legitimized knowledge in society. -

TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld June 2017 • Shavuot 5777 a Special Edition Celebrating President Richard M

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future THE BENJAMIN AND ROSE BERGER TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld June 2017 • Shavuot 5777 A Special Edition Celebrating President Richard M. Joel WITH SHAVUOT TRIBUTES FROM Rabbi Dr. Kenneth Brander • Rabbi Dr. Hillel Davis • Rabbi Dr. Avery Joel • Dr. Penny Joel Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph • Rabbi Menachem Penner • Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacter • Rabbi Ezra Schwartz Special Symposium: Perspectives on Conversion Rabbi Eli Belizon • Joshua Blau • Mrs. Leah Nagarpowers • Rabbi Yona Reiss Rabbi Zvi Romm • Mrs. Shoshana Schechter • Rabbi Michoel Zylberman 1 Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Shavuot 5777 We thank the following synagogues which have pledged to be Pillars of the Torah To-Go® project Beth David Synagogue Green Road Synagogue Young Israel of West Hartford, CT Beachwood, OH Century City Los Angeles, CA Beth Jacob Congregation The Jewish Center Beverly Hills, CA New York, NY Young Israel of Bnai Israel – Ohev Zedek Young Israel Beth El of New Hyde Park New Hyde Park, NY Philadelphia, PA Borough Park Koenig Family Foundation Young Israel of Congregation Brooklyn, NY Ahavas Achim Toco Hills Atlanta, GA Highland Park, NJ Young Israel of Lawrence-Cedarhurst Young Israel of Congregation Cedarhurst, NY Shaarei Tefillah West Hartford West Hartford, CT Newton Centre, MA Richard M. Joel, President and Bravmann Family University Professor, Yeshiva University Rabbi Dr. Kenneth -

Temple Emanu-El Newsletter

Temple Emanu-El TEN Newsletter ISDN I E TEN VOLUME 92 NUMBER 2 | FEBRUARY - JUNE 2018 | SHEVAT/ADAR/NISAN/IYYAR/SIVAN/TAMUZ 5778 2 Letters 4 B’nai Mitzvahs Choice: The Foundation of Freedom 7 Contributions by Rabbi David-Seth Kirshner 14 Holidays 18 Upcoming Events 26 Sisterhood Chocolate or Vanilla? Democrat or Republican? Jersey Shore or the Hamptons? Our lives are full of choices. Some are trivial and will have very little impact on 29 Men’s Club the shaping of our future. Other decisions like who we marry, taking a specific job or moving to a new city all provide a different fundamental canvas that allows for the portrait of our lives to be painted. Sometimes, even the simplest decision of taking the day off on September 11, or missing a flight can make all of the impact that you could never anticipate. READ THE FULL MESSAGE FROM RABBI KIRSHNER ON THE NEXT PAGE > A LETTER FROM OUR RAbbI Choice: The Foundation of Freedom Chocolate or Vanilla? Democrat or Republican? Jersey Shore or the Hamptons? Our lives are full of choices. Some are trivial and will have very little impact on the shaping of our future. Other decisions like who we marry, taking a specific job or moving to a new city all provide a different fundamental canvas that allows for the portrait of our lives to be painted. Sometimes, even the simplest decision of taking the day off on September 11, or missing a flight can make all of the impact that you could never anticipate. Choice is rarely appreciated.