Network Analysis of Mineralogical Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Evolutionary System of Mineralogy: Proposal for a Classification Of

1 1 02 November 2018—American Mineralogist—Revision 1 2 3 4 An evolutionary system of mineralogy: Proposal for a classification 5 of planetary materials based on natural kind clustering 6 7 ROBERT M. HAZEN1,* 8 1Geophysical Laboratory, Carnegie Institution for Science, 9 5251 Broad Branch Road NW, Washington, DC 20015, U. S. A. 10 11 ABSTRACT 12 Minerals reveal the nature of the co-evolving geosphere and biosphere through billions of years 13 of Earth history. Mineral classification systems have the potential to elucidate this rich 14 evolutionary story; however, the present mineral taxonomy, based as it is on idealized major 15 element chemistry and crystal structure, lacks a temporal aspect and thus cannot reflect planetary 16 evolution. A complementary evolutionary system of mineralogy based on the quantitative 17 recognition of “natural kind clustering” for a wide range of condensed planetary materials with 18 different paragenetic origins has the potential to amplify, though not supersede, the present 19 classification system. 20 21 _________________________________ 22 *E-mail: [email protected] 23 Keywords: philosophy of mineralogy; classification; mineral evolution; mineral ecology; data- 24 driven discovery; cluster analysis; natural kinds 2 25 INTRODUCTION 26 For more than 2000 years, the classification of natural objects and phenomena into “kinds” has 27 been a central pursuit of natural philosophers (Aristotle/Thompson 1910; Locke 1690; Linnaeus 28 1758). The modern mineral classification system, rooted in the chemical framework of James 29 Dwight Dana (1850), is based on unique combinations of idealized major element composition 30 and crystal structure (Strunz 1941; Palache et al. 1944, 1951; Liebau 1985; Mills et al. -

Persson Mines 0052N 11296.Pdf

THE GEOCHEMICAL AND MINERALOGICAL EVOLUTION OF THE MOUNT ROSA COMPLEX, EL PASO COUNTY, COLORADO, USA by Philip Persson A thesis submitted to the Faculty and Board of Trustees of the Colorado School of Mines in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (Geology). Golden, Colorado Date ________________ Signed: ________________________ Philip Persson Signed: ________________________ Dr. Katharina Pfaff Thesis Advisor Golden, Colorado Date ________________ Signed: ________________________ Dr. M. Stephen Enders Professor and Interim Head Department of Geology and Geological Engineering ii ABSTRACT The ~1.08 Ga Pikes Peak Batholith is a type example of an anorogenic (A)-type granite and hosts numerous late-stage sodic and potassic plutons, including the peraluminous to peralkaline Mount Rosa Complex (MRC), located ~15 km west of the City of Colorado Springs in Central Colorado. The MRC is composed of Pikes Peak biotite granite, fayalite-bearing quartz syenite, granitic dikes, Mount Rosa Na-Fe amphibole granite, mafic dikes ranging from diabase to diorite, and numerous rare earth (REE) and other high field strength element (HFSE; e.g. Th, Zr, Nb) rich Niobium-Yttrrium-Fluorine (NYF)-type pegmatites. The aim of this study is to trace the magmatic evolution of the Mount Rosa Complex in order to understand the relationship between peraluminous and peralkaline rock units and concomitant HFSE enrichment and mineralization processes. Field work, petrography, SEM-based methods, whole rock geochemistry, and electron probe micro-analysis (EPMA) of micas was performed on all rock units to determine their textural, mineralogical and geochemical characteristics. Early peraluminous units such as the Pikes Peak biotite granite and fayalite-bearing quartz syenite contain annite-siderophyllite micas with high Fe/(Fe + Mg) ratios, and show relatively minor enrichments in REE and other HFSE compared to primitive mantle. -

Minor- and Trace-Element Composition of Trioctahedral Micas: a Review

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/249851431 Minor- and trace-element composition of trioctahedral micas: A review Article in Mineralogical Magazine · April 2001 DOI: 10.1180/002646101550244 CITATIONS READS 100 1,145 3 authors, including: H.-J. Förster Helmholtz-Zentrum Potsdam - Deutsches GeoForschungsZentrum GFZ 297 PUBLICATIONS 6,380 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Special Issue of journal Minerals on Accessory Minerals in Silicic Igneous Rocks View project Geochemistry of late-Variscan granites of the Erzgebirge-Vogtland metallogenic province View project All content following this page was uploaded by H.-J. Förster on 06 May 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Mineralogical Magazine, April 2001, Vol. 65(2), pp. 249–276 Minor- and trace-element composition of trioctahedral micas: a review 1 2, 2 G. TISCHENDORF , H.-J. FO¨ RSTER * AND B. GOTTESMANN Bautzner Str. 16, 02763 Zittau, Germany GeoForschungsZentrum Potsdam, Telegrafenberg, 14473 Potsdam, Germany ABSTRACT More than 19,000 analytical data mainly from the literature were used to study statistically the distribution patterns of F and the oxides of minor and trace elements (Ti, Sn, Sc, V, Cr, Ga, Mn, Co, Ni, Zn, Sr, Ba, Rb, Cs) in trioctahedral micas of the system phlogopite-annite/siderophyllite- polylithionite (PASP), which is divided here into seven varieties, whose compositional ranges are defined by the parameter mgli (= octahedral Mg minus Li). Plots of trace-element contents vs. mgli reveal that the elements form distinct groups according to the configuration of their distribution patterns. -

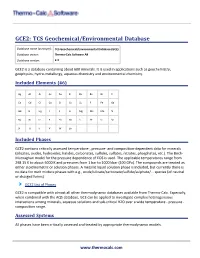

GCE2 Database Information

GCE2: TCS Geochemical/Environmental Database Database name (acronym): TCS Geochemical/Environmental Database (GCE) Database owner: Thermo-Calc Software AB Database version: 2.4 GCE2 is a database containing about 600 minerals. It is used in applications such as geochemistry, geophysics, hydro-metallurgy, aqueous chemistry and environmental chemistry. Included Elements (46) Ag Al Ar As Au B Ba Be Br C Ca Cd Cl Co Cr Cs Cu F Fe Ga Gd H Hg I K Li Mg Mn Mo N Na Ni O P Pb Rb S Se Si Sn Sr Ti U V W Zn Included Phases GCE2 contains critically assessed temperature-, pressure- and composition-dependent data for minerals (silicates, oxides, hydroxides, halides, carbonates, sulfides, sulfates, nitrates, phosphates, etc.). The Birch- Murnaghan model for the pressure dependence of EOS is used. The applicable temperatures range from 298.15 K to about 6000 K and pressures from 1 bar to 1000 kbar (100 GPa). The compounds are treated as either stoichiometric or solution phases. A metallic liquid solution phase is included, but currently there is no data for melt mixture phases with e.g., oxide/silicate/carbonate/sulfide/sulphate/... species (of neutral or charged forms). GCE2 List of Phases GCE2 is compatible with almost all other thermodynamic databases available from Thermo-Calc. Especially, when combined with the AQS database, GCE can be applied to investigate complex heterogeneous interactions among minerals, aqueous solutions and sub-critical H2O over a wide temperature - pressure - composition range. Assessed Systems All phases have been critically assessed and treated by appropriate thermodynamic models. www.thermocalc.com GCE2: TCS Geochemical/Environmental Database ǀ 2 of 27 Limits As in the spirit of the CALPHAD method, predictions can be made for multicomponent systems by extrapolation into multicomponent space of data critically evaluated and assessed based on binary, ternary and in some cases higher order systems. -

Studies in the Mica Group; Single Crystal Data on Phlogopites, Biotites and Manganophyllites A

STUDIES IN THE MICA GROUP; SINGLE CRYSTAL DATA ON PHLOGOPITES, BIOTITES AND MANGANOPHYLLITES A. A. LBvTNSoNAND E. Wu. Horwucu, Department oJ Mineralogy, The Ohio State [Inioersity, Columbus, Ohio, and. Department of Minerology, Uni.aersityoJ Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigon. AssrnA.ct Weissenberg studies of about 250 specimens of phlogopite, biotite and manganophyllite, of which 63 have been chemically analyzed, indicate: (1) in phlogopites there is no dis- cernible relationship between structure and either composition or paragenesis; (2) in biotites there is no relationship between structure and composition, but geologic environ- ment may be a factor in determining the polymorphic type; (3) the optic plane of all 2-layer polymorphs is normal to (010), as is also the case for the biotite variety, anomitel and (4) lJayer polymorphs nearly always have the optic plane parallel with (010), which corresponds with the orientation of the biotite variety, meroxene. IxrnooucuoN Systematic variations between composition and the various poly- morphs in the muscovite-lepidolite series have been demonstrated by Levinson (1953). On the basis of these results it seemeddesirable to investigate the biotite-phlogopite seriesin a similar manner in the hope of gaining insight into causes of the complex polymorphism known to exist in these micas. The only other Weissenbergstudy of these micas known to the writers is in the work of Hendricks and Jefferson (1939), predominantly on unanalyzed specimens. We have obtained over 60 analyzed specimensof biotite, phlogopite and manganophyllite (which we consider as manganoan phlogopite), most of which have been describedby several investigators. In addition we have studied a suite of approximately 200 unanalyzed biotites and phlogopites from geologically well-studied occurrences. -

A Specific Gravity Index for Minerats

A SPECIFICGRAVITY INDEX FOR MINERATS c. A. MURSKyI ern R. M. THOMPSON, Un'fuersityof Bri.ti,sh Col,umb,in,Voncouver, Canad,a This work was undertaken in order to provide a practical, and as far as possible,a complete list of specific gravities of minerals. An accurate speciflc cravity determination can usually be made quickly and this information when combined with other physical properties commonly leads to rapid mineral identification. Early complete but now outdated specific gravity lists are those of Miers given in his mineralogy textbook (1902),and Spencer(M,i,n. Mag.,2!, pp. 382-865,I}ZZ). A more recent list by Hurlbut (Dana's Manuatr of M,i,neral,ogy,LgE2) is incomplete and others are limited to rock forming minerals,Trdger (Tabel,l,enntr-optischen Best'i,mmungd,er geste,i,nsb.ildend,en M,ineral,e, 1952) and Morey (Encycto- ped,iaof Cherni,cal,Technol,ogy, Vol. 12, 19b4). In his mineral identification tables, smith (rd,entifi,cati,onand. qual,itatioe cherai,cal,anal,ys'i,s of mineral,s,second edition, New york, 19bB) groups minerals on the basis of specificgravity but in each of the twelve groups the minerals are listed in order of decreasinghardness. The present work should not be regarded as an index of all known minerals as the specificgravities of many minerals are unknown or known only approximately and are omitted from the current list. The list, in order of increasing specific gravity, includes all minerals without regard to other physical properties or to chemical composition. The designation I or II after the name indicates that the mineral falls in the classesof minerals describedin Dana Systemof M'ineralogyEdition 7, volume I (Native elements, sulphides, oxides, etc.) or II (Halides, carbonates, etc.) (L944 and 1951). -

Mineralogy and Mineral Chemistry of Rare-Metal Pegmatites at Abu Rusheid Granitic Gneisses, South Eastern Desert, Egypt

GEOLOGIJA 54/2, 205–222, Ljubljana 2011 doi:10.5474/geologija.2011.016 Mineralogy and mineral chemistry of rare-metal pegmatites at Abu Rusheid granitic gneisses, South Eastern Desert, Egypt Mohamed F. RASLAN & Mohamed A. ALI Nuclear Materials Authority, P.O. Box 530, El Maadi, Cairo, Egypt; e-mail: raslangains�hotmail.com Prejeto / Received 28. 2. 2011; Sprejeto / Accepted 22. 6. 2011 Key words: Hf-zircon, uranyl silicate minerals, Nb-Ta minerals, uraninite, Abu Rushied pegmatite, South Eastern Desert, Egypt Abstract The Abu Rushied area, situated in the South Eastern Desert of Egypt is a distinctive occurrence of economically important rare-metal mineralization where the host rocks are represented by granitic gneisses. Correspondingly, mineralogical and geochemical investigation of pegmatites pockets scattered within Abu Rusheid granitic gneisses revealed the presence of Hf-zircon, ferrocolumbite and uranyl silicate minerals (uranophane and kasolite). Elec- tron microprobe analyses revealed the presence of Nb-Ta multioxide minerals (ishikawaite, uranopyrochlore, and fergusonite), uraninite, thorite and cassiterite as numerous inclusions in the recorded Hf-zircon and ferrocolum- bite minerals. Abu Rusheid pegmatites are found as small and large bodies that occur as simple and complex (zoned) pegma- tites. Abu Rusheid rare-metal pegmatites occur as steeply dipping bodies of variable size, ranging from 1 to 5 m in width and 10 to 50 m in length. The zoned pegmatites are composed of wall zone of coarser granitic gneisses, intermediated zone of K-feldspar and pocket of mica (muscovite and biotite), and core of quartz and pocket of mica with lenses of rare metals. The zircon is of bipyramidal to typical octahedral form and short prisms. -

Mineral Deposit Models for Northeast Asia

Mineral Deposit Models for Northeast Asia By Alexander A. Obolenskiy1, Sergei M. Rodionov2, Sodov Ariunbileg3, Gunchin Dejidmaa4, Elimir G. Distanov1, Dangindorjiin Dorjgotov5, Ochir Gerel6, Duk Hwan Hwang7, Fengyue Sun8, Ayurzana Gotovsuren9, Sergei N. Letunov10, Xujun Li8, Warren J Nokleberg11, Masatsugu Ogasawara12, Zhan V. Seminsky13, Akexander P. Smelov14, Vitaly I. Sotnikov1, Alexander A. Spiridonov10, Lydia V. Zorina10, and Hongquan Yan8 1 Russian Academy of Sciences, Novosibirsk 2 Russian Academy of Sciences, Khabarovsk 3 Mongolian Academy of Sciences, Ulaanbaatar 4 Mineral Resources Authority of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar 5 Mongolian National University, Ulaanbaatar 6 Mongolian University of Science and Technology, Ulaanbaatar 7 Korea Institute of Geology, Mining, and Materials, Taejon 8 Jilin University, Changchun, China 9 Mongolia Ministry of Industry and Commerce, Ulaanbaatar 10 Russian Academy of Sciences, Irkutsk 11 U.S. Geological Survey, Menlo Park 12 Geological Survey of Japan/AIST, Tsukuba 13 Irkutsk State Technical University, Irkutsk 14 Russian Academy of Sciences, Yakutsk This article is prepared by a large group of Russian, Chinese, Mongolian, South Korean, Introduction and Companion Japanese, Studies and USA geologists who are members of the joint Metalliferous and selected non-metalliferous lode international project on Major Mineral Deposits, and placer deposits for Northeast Asia are classified Metallogenesis, and Tectonics of the Northeast Asia. into various models or types described below. The This project is being conducted by the Russian mineral deposit types used in this report are based on Academy of Sciences, the Mongolian Academy of both descriptive and genetic information that is Sciences, Mongolian National University, Mongolian systematically arranged to describe the essential Technical University, the Mineral Resources Authority properties of a class of mineral deposits. -

United States Department of the Interior Geological

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY SPVIEW Spectral Plot Program for Accessing the USGS Digital Spectral Library Database with MS - DOS Personal Computers VERSION 1.00 by K. Eric Livo, Roger N. Clark, and Daniel H. Knepper, Jr. Open-File Report 93-593 November, 1993 93 - 593 A Documentation (Paper Copy) 93 - 593 B 3 MS-DOS 3.5 inch diskettes containing Executable Programs, Source Code, Digital Mineral Spectral Library, and Digital Documentation This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with the U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards. Use of trade names in this report is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the USGS. Although these programs have been extensively tested, the USGS makes no guarantee of correct results. U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, Colorado 80225 Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................ i Introduction .............................. 1 Files Contained in This Release ..................... 2 \SPECTRA .............................. 2 \SPECTRA\SOURCE .......................... 2 Installation .............................. 4 Operation ................................ 4 Public Domain .............................. 6 Requirements .............................. 6 Program Users Guide ........................... 7 SPVIEW ............................... 7 main screen (expanded table of contents) ........... 7 main screen (collapsed table of contents) ........... 8 read record .......................... 8 text info (<r> read record-expanded -

Crystal Chemical Variations in Li- and Fe-Rich Micas from Pikes Peak Batholith (Central Colorado)

American Mineralogist, Volume 85, pages 1275–1286, 2000 Crystal chemical variations in Li- and Fe-rich micas from Pikes Peak batholith (central Colorado) MARIA FRANCA BRIGATTI,*,1 CRISTINA LUGLI,1 LUCIANO POPPI,1 EUGENE E. FOORD,† AND DANIEL E. KILE2 1Department of Earth Sciences, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, 41100 Modena, Italy 2United States Geological Survey, Denver, Colorado 80225, U.S.A. ABSTRACT The crystal structure and M-site populations of a series of micas-1M from miarolitic pegmatites that formed within host granitic rocks of the Precambrian, anorogenic Pikes Peak batholith, central Colorado, were determined by single-crystal X-ray diffraction data. Crystals fall in the polylithionite- [6] siderophyllite-annite field, being 0 ≤ Li ≤ 2.82, 0.90 ≤ Fetotal ≤ 5.00, 0.26 ≤ Al ≤ 2.23 apfu. Ordering of trivalent cations (mainly Al3+) is revealed in a cis-octahedral site (M2 or M3), which leads to a lowering of the layer symmetry from C12/m(1) (siderophyllite and annite crystals) to C12(1) diperiodic group (lithian siderophyllite and ferroan polylithionite crystals). On the basis of mean bond length, the ordering scheme of octahedral cations is mostly meso-octahedral, whereas the mean electron count at each M site suggests both meso- and hetero-octahedral ordering, the calculated mean atomic numbers being M1 = M3 ≠ M2, M2 = M3 ≠ M1 and M1 ≠ M2 ≠ M3. As the siderophyllite content increases, so do the a, b, and c unit-cell parameters, as well as the refractive indices, primarily nβ. The tetrahedral rotation angle, α, is generally small (1.51 ≤ α ≤ 5.04°) and roughly increases with polylithionite content, whereas the basal oxygen out-of-plane tilting, ∆z, is sensitive both to octahe- dral composition and degree of order (0.0 ≤ ∆z ≤ 0.009 Å for siderophyllite and annite, 0.058 ≤ ∆z ≤ 0.144 Å for lithian siderophyllite and ferroan polylithionite crystals). -

Nomenclature of the Micas

Mineralogical Magazine, April 1999, Vol. 63(2), pp. 267-279 Nomenclature of the micas M. RIEDER (CHAIRMAN) Department of Geochemistry, Mineralogy and Mineral Resources, Charles University, Albertov 6, 12843 Praha 2, Czech Republic G. CAVAZZINI Dipartimento di Mineralogia e Petrologia, Universith di Padova, Corso Garibaldi, 37, 1-35122 Padova, Italy Yu. S. D'YAKONOV VSEGEI, Srednii pr., 74, 199 026 Sankt-Peterburg, Russia W. m. FRANK-KAMENETSKII* G. GOTTARDIt S. GUGGENHEIM Department of Geological Sciences, University of Illinois at Chicago, 845 West Taylor St., Chicago, IL 60607-7059, USA P. V. KOVAL' Institut geokhimii SO AN Rossii, ul. Favorskogo la, Irkutsk - 33, Russia 664 033 G. MOLLER Institut fiir Mineralogie und Mineralische Rohstoffe, Technische Universit/it Clausthal, Postfach 1253, D-38670 Clausthal-Zellerfeld, Germany A. M, R. NEIVA Departamento de Ci6ncias da Terra, Universidade de Coimbra, Apartado 3014, 3049 Coimbra CODEX, Portugal E. W. RADOSLOVICH$ J.-L. ROBERT Centre de Recherche sur la Synth6se et la Chimie des Min6raux, C.N.R.S., 1A, Rue de la F6rollerie, 45071 Od6ans CEDEX 2, France F. P. SASSI Dipartimento di Mineralogia e Petrologia, Universit~t di Padova, Corso Garibaldi, 37, 1-35122 Padova, Italy H. TAKEDA Chiba Institute of Technology, 2-17-1 Tsudanuma, Narashino City, Chiba 275, Japan Z. WEISS Central Analytical Laboratory, Technical University of Mining and Metallurgy, T/'. 17.1istopadu, 708 33 Ostrava- Poruba, Czech Republic AND D. R. WONESw * Russia; died 1994 t Italy; died 1988 * Australia; resigned 1986 wUSA; died 1984 1999 The Mineralogical Society M. RIEDER ETAL. ABSTRACT I I End-members and species defined with permissible ranges of composition are presented for the true micas, the brittle micas, and the interlayer-deficient micas. -

Corrigendum 2

Vol. 55, No. 6, 2007 Clay mineralogy nomenclature 647 Table 1. Classification of planar hydrous phyllosilicates. Layer Interlayer material1 Group Octahedral Species2 type character 1:1 None or H2O only Serpentine-kaolin Trioctahedral Lizardite, berthierine, amesite, cronstedtite (x & 0) Dioctahedral Kaolinite, dickite, nacrite, halloysite (planar) Di,trioctahedral Odinite ———————————————————————————————— 2:1 None (x & 0) Talc-pyrophyllite Trioctahedral Talc, willemseite, kerolite, pimelite Dioctahedral Pyrophyllite, ferripyrophyllite Hydrated exchangeable Smectite Trioctahedral Saponite, hectorite, sauconite, stevensite, swinefordite cations (x & 0.2À0.6) Dioctahedral Montmorillonite, beidellite, nontronite, volkonskoite Hydrated exchangeable Vermiculite Trioctahedral Trioctahedral vermiculite cations (x & 0.6À0.9) Dioctahedral Dioctahedral vermiculite Non-hydrated mono- or Interlayer-deficient Trioctahedral Wonesite3,4 divalent cations mica Dioctahedral none4 (x & 0.6À0.85) Non-hydrated True (flexible) Trioctahedral Phlogopite, siderophyllite, aspidolite monovalent cations, mica Dioctahedral Muscovite, celadonite, paragonite (550% monovalent, x & 0.85À1.0 for dioctahedral) Non-hydrated divalent Brittle mica Trioctahedral Clintonite, kinoshitalite, bityite, anandite cations, (550% divalent, Dioctahedral Margarite, chernykhite x & 1.8À2.0) Hydroxide sheet Chlorite Trioctahedral Clinochlore, chamosite, pennantite, nimite, baileychlore (x = variable) Dioctahedral Donbassite Di,trioctahedral Cookeite, sudoite Tri,dioctahedral none ————————————————————————————————