Historic Soil Conservation at Malabar Farm, 1939-1972

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saving the Dust Bowl: “Big Hugh” Bennett’S Triumph Over Tragedy

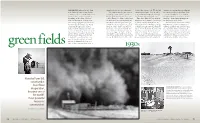

Saving the Dust Bowl: “Big Hugh” Bennett’s Triumph over Tragedy Rebecca Smith Senior Historical Paper “It was dry everywhere . and there was entirely too much dust.” -Hugh Hammond Bennett, visit to the Dust Bowl, 19361 Merciless winds tore up the soil that once gave the Southern Great Plains life and hurled it in roaring black clouds across the nation. Hopelessly indebted farmers fed tumbleweed to their cattle, and, in the case of one Oklahoma town, to their children. By the 1930s, years of injudicious cultivation had devastated 100 million acres of Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, Colorado, and New Mexico.2 This was the Dust Bowl, and it exposed a problem that had silently plagued American agriculture for centuries–soil erosion. Farmers, scientists, and the government alike considered it trivial until Hugh Hammond Bennett spearheaded a national program of soil conservation. “The end in view,” he proclaimed, “is that people everywhere will understand . the obligation of respecting the earth and protecting it in order that they may enjoy its fullness.” 3 Because of his leadership, enthusiasm, and intuitive understanding of the American farmer, Bennett triumphed over the tragedy of the Dust Bowl and the ignorance that caused it. Through the Soil Conservation Service, Bennett reclaimed the Southern Plains, reformed agriculture’s philosophy, and instituted a national policy of soil conservation that continues today. The Dust Bowl tragedy developed from the carelessness of plenty. In the 1800s, government and commercial promotions encouraged negligent settlement of the Plains, lauding 1 Hugh Hammond Bennett, Soil Conservation in the Plains Country, TD of address for Greater North Dakota Association and Fargo Chamber of Commerce Banquet, Fargo, ND., 26 Jan. -

Ohiocontrolled Hunting

CONTROLLED HUNTING OHIO OPPORTUNITIES 2020-2021 Application period JULY 1, 2020 to JULY 31, 2020 OHIO DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF WILDLIFE wildohio.gov OHIO DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF WILDLIFE The Division of Wildlife’s mission is to conserve and improve fish and wildlife resources and their habitats for sustainable use and appreciation by all. VISIT US ON THE WEB WILDOHIO.GOV FOR GENERAL INFORMATION 1-800-WILDLIFE (1-800-945-3543) TO REPORT WILDLIFE VIOLATIONS 1-800-POACHER (1-800-762-2437) DIVISION OF WILDLIFE **AVAILABLE 24 HOURS** DISTRICT OFFICES OHIO GAME CHECK OHIOGAMECHECK.COM WILDLIFE DISTRICT ONE 1500 Dublin Road 1-877-TAG-IT-OH Columbus, OH 43215 (1-877-824-4864) (614) 644‑3925 WILDLIFE DISTRICT TWO HIP CERTIFICATION 952 Lima Avenue 1-877-HIP-OHIO Findlay, OH 45840 (1-877-447-6446) (419) 424‑5000 WILDLIFE DISTRICT THREE FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA 912 Portage Lakes Drive Akron, OH 44319 Like us on Facebook (330) 644‑2293 facebook.com/ohiodivisionofwildlife Follow us on Twitter WILDLIFE DISTRICT FOUR twitter.com/OhioDivWildlife 360 E. State Street Athens, OH 45701 (740) 589‑9930 WILDLIFE DISTRICT FIVE 1076 Old Springfield Pike Xenia, OH 45385 (937) 372‑9261 EQUAL OPPORTUNITY The Ohio Division of Wildlife offers equal opportunity regardless GOVERNOR, STATE OF OHIO of race, color, national origin, age, disability or sex (in education programs). If you believe you have been discriminated against in MIKE DeWINE any program, activity or facility, you should contact: The U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Diversity & Civil Rights Programs-External Programs, DIRECTOR, OHIO DEPARTMENT 4040 N. -

Morrone, Michele Directo

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 417 064 SE 061 114 AUTHOR Mourad, Teresa; Morrone, Michele TITLE Directory of Ohio Environmental Education Sites and Resources. INSTITUTION Environmental Education Council of Ohio, Akron. SPONS AGENCY Ohio State Environmental Protection Agency, Columbus. PUB DATE 1997-12-00 NOTE 145p. AVAILABLE FROM Environmental Education Council of Ohio, P.O. Box 2911, Akron, OH 44309-2911; or Ohio Environmental Education Fund, Ohio Environmental Protection Agency, P.O. Box 1049, Columbus, OH 43216-1049. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Agencies; Conservation Education; Curriculum Enrichment; Ecology; Educational Resources; Elementary Secondary Education; *Environmental Education; *Experiential Learning; *Field Trips; Hands on Science; History Instruction; Learning Activities; Museums; Nature Centers; *Outdoor Education; Parks; Planetariums; Recreational Facilities; *Science Teaching Centers; Social Studies; Zoos IDENTIFIERS Gardens; Ohio ABSTRACT This publication is the result of a collaboration between the Environmental Education Council of Ohio (EECO) and the Office of Environmental Education at the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (OEPA). This directory of environmental education resources within the state of Ohio is intended to assist educators in finding information that can complement local curricula and programs. The directory is divided into three sections. Section I contains information on local environmental education sites and resources. These are grouped by EECO region, alphabetized by county, and further alphabetized by organization name. Resources range from arboretums to zoos. Section II lists resources available at a statewide level. These include state and federal government agencies, environmental education organizations and programs, and resource persons. Section III contains cross-referenced lists of Section I by organization name, audience, organization type, and programs and services to help educators identify local resources. -

2007 Study Plan for the Walhonding Watershed (Richland, Ashland, Wayne, Morrow Knox, Holmes and Coshocton Counties, OH)

Ohio EPA/DSW/MAS-EAU 2007 Walhonding Watershed Study Plan May 9, 2007 2007 Study Plan for the Walhonding Watershed (Richland, Ashland, Wayne, Morrow Knox, Holmes and Coshocton Counties, OH) State of Ohio Environmental Protection Agency Division of Surface Water Lazarus Government Center 122 South Front St., Columbus, OH 43215 Mail to: P.O. Box 1049, Columbus, OH 43216-1049 & Monitoring and Assessment Section 4675 Homer Ohio Lane Groveport, OH 43125 & Surface Water Section Central District Office 50 West Town St., Suite 700 Columbus, OH 43215 & Surface Water Section Northwest District Office 347 North Dunbridge Rd. Bowling Green, OH 434o2 & Surface Water Section Southeast District Office 2195 Front Street Logan, OH 43138 1 Ohio EPA/DSW/MAS-EAU 2007 Walhonding Watershed Study Plan May 9, 2007 Introduction: During the 2007 field season (June thru October) chemical, physical, and biological sampling will be conducted in the Walhonding watershed to assess and characterize water quality conditions. Sample locations were either stratified by drainage area or selected to ensure adequate representation of principal linear reaches. In addition, some sites were selected to support development of Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) models or because they are part of Ohio EPA’s reference data set. Four major municipal and two major industrial NPDES permitted entities exist in the study area (Table 1). Beyond assuring that sample locations were adequate to assess these potential influences, the survey was broadly structured to characterize possible effects from other pollution sources. These sources include minor permitted discharges, unsewered communities, agricultural or industrial activities, and oil, gas or mineral extraction. -

Hugh Hammond Bennett

Hugh Hammond Bennett nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/national/about/history/ "Father of Soil Conservation" Hugh Hammond Bennett (April 15 1881-7 July 1960) was born near Wadesboro in Anson County, North Carolina, the son of William Osborne Bennett and Rosa May Hammond, farmers. Bennett earned a bachelor of science degree an emphasis in chemistry and geology from the University of North Carolina in June 1903. At that time, the Bureau of Soils within the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) had just begun to make county-based soil surveys, which would in the time be regarded as important American contributions to soil science. Bennett accepted a job in the bureau headquarters' laboratory in Washington, D.C., but agreed first to assist on the soil survey of Davidson County, Tennessee, beginning 1 July 1903. The acceptance of that task, in Bennett's words, "fixed my life's work in soils." The outdoor work suited Bennett, and he compiled a number of soil surveys. The 1905 survey of Louisa County, Virginia, in particular, profoundly affected Bennett. He had been directed to the county to investigate its reputation of declining crop yields. As he compared virgin, timbered sites to eroded fields, he became convinced that soil erosion was a problem not just for the individual farmer but also for rural economies. While this experience aroused his curiosity, it was, according to Bennett's recollection shortly before his death, Thomas C. Chamberlain's paper on "Soil Wastage" presented in 1908 at the Governors Conference in the White House (published in Conference of Governors on Conservation of Natural Resources, ed. -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

Forest History Today Spring/Fall 2014

A PUBLICATION OF THE FOREST HISTORY SOCIETY SPRING/FALL 2014 VOL. 20, NOS. 1 & 2 MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT “Not everybody trusts paintings but people believe photographs.”–Ansel Adams STEVEN ANDERSON hen Gifford Pinchot hired the first come from both the FHS Photograph Collec - forest rangers in the U.S. Forest tion and from institutional and individual col- WService, he outfitted them with cam- laborators. By providing an authoritative site eras and asked them to document what they did on the subject, we expect to identify previously and saw. He knew the power the photographs unknown repeat photographic pairs and could wield as he fought for funds to manage sequences, promote the creation of new repeat the nation’s forests and sought public support sets, and foster interest in the future uses of for new policies. No one can deny that visual repeat photography. images have played an important role in the con- Sally Mann, a renowned American landscape servation and environmental movements. and portrait photographer, said, “Photographs That is why, from its beginnings in 1946, the open doors into the past, but they also allow a Forest History Society has collected and pre- look into the future.” We hope that providing served photographs of early lumbering tech- access to and stimulating more work in repeat niques, forest products, forest management, photography will help students, teachers, jour- and other subjects. The FHS staff has already helped thousands nalists, foresters, and many others gain insight that can elevate of students, writers, and scholars find historic photographs that our awareness of conservation challenges. -

How the Farm Bill, Conceived in Dust Bowl Desperation, Became One Of

IT WAS THE 1930S, and rural people clung sugarbeet, dust rose to meet their gaze. because there was no feed. We also had extensive root systems that can withstand to the land as if it were a part of them, “The dust storms, they just come in a grasshopper plague. There would be the extreme weather on the plains. While as integral as bone or sinew. But the land boiling like angry clouds,” remembers so many flying, they would darken the a nine-year drought has been dragging betrayed them—or they betrayed it, Maxine Nickelson, 81, who lives near sun. It was really, really hard times.” the region by the heels, farmers—and the depending on the telling of history. Oakley, Kansas, less than 10 miles from Times have changed. Now, when the landscape—aren’t facing anything near In the black-and-white portraits of the the farm where she grew up during the wind blows at The Nature Conservancy’s the desperation of the 1930s. time, dismay is palpable, grooves of anx- Dust Bowl. “The dust piles would get 17,000-acre Smoky Valley Ranch, 15 That the country hasn’t seen another iety worn deep around the eyes. In scat- so high they’d cover up the fence posts miles south of where Nickelson grew up, Dust Bowl is testament to advances in tered fields throughout the country, along the roads. Yeah, it was bad. We it whispers through a thriving shortgrass farming equipment and cultivation prac- farmers took the stitching out of the soil had to use a scoop shovel to take dirt prairie. -

Iowa Soil and Water Conservation Commissioner Handbook

IOWA SOIL AND WATER CONSERVATION COMMISSIONER HANDBOOK Written in joint cooperation by: • Conservation Districts of Iowa • Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship - Division of Soil Conservation and Water Quality • Natural Resources Conservation Service Revised: 12.15.2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Topic Page Preface 3 History and Development of Soil and Water Conservation Districts 4 Organization of Soil and Water Conservation Districts Under State Law 6 The District Board 10 District Administration 14 District Plans and Planning Activities 19 Commissioner Development and Training 22 Partner Agencies and Organizations Working with Districts 23 Legal and Ethical Issues 29 Appendix A: Acronyms 32 Appendix B: References and Resources 34 Appendix C: Sediment Control Law 35 Appendix D: Map of CDI Regions 36 Appendix E: Map of IDALS Field Representative Areas 37 Appendix F: Map of NRCS Areas 38 Appendix G: Financial Checklist 39 Appendix H: Financial Policies Annual Checklist 40 2 PREFACE Congratulations upon election to your local Soil and Water Conservation District Board and welcome to your role as a Soil and Water Conservation District Commissioner in the State of Iowa. As a Commissioner, you are a locally elected conservation leader; understanding your role and responsibilities as a Commissioner will assist you to effectively promote and implement conservation in your community. This Iowa Soil and Water Conservation District Commissioner Handbook provides you with an orientation to your role and responsibilities. Every effort has been made to make this handbook beneficial. Please note that this handbook is a basic resource for commissioners. The general statement of powers, duties, and specific provisions of the Conservation Districts are contained in Iowa Code Chapter 161A. -

Readings in the History of the Soil Conservation Service

United States Department of Agriculture Readings in the Soil Conservation Service History of the Soil Conservation Service Economics and Social Sciences Division, NHQ Historical Notes Number 1 Introduction The articles in this volume relate in one way or another to the history of the Soil Conservation Service. Collectively, the articles do not constitute a comprehensive history of SCS, but do give some sense of the breadth and diversity of SCS's missions and operations. They range from articles published in scholarly journals to items such as "Soil Conservation: A Historical Note," which has been distributed internally as a means of briefly explaining the administrative and legislative history of SCS. To answer reference requests I have made reprints of the published articles and periodically made copies of some of the unpublished items. Having the materials together in a volume is a very convenient way to satisfy these requests in a timely manner. Also, since some of these articles were distributed to SCS field offices, many new employees have joined the Service. I wanted to take the opportunity to reach them. SCS employees are the main audience. We have produced this volume in the rather unadorned and inexpensive manner so that we can distribute the volume widely and have it available for training sessions and other purposes. Also we can readily add articles in the future. If anyone should wish to quote or cite any of the published articles, please use the citations provided at the beginning of the article. For other articles please cite this publication. Steven Phillips, a graduate student in history at Georgetown University and a 1992 summer intern here with SCS, converted the articles to this uniform format, and is hereby thanked for his very professional efforts. -

Mors Loaded 8/1/05 - 8/2/05

MORs Loaded 8/1/05 - 8/2/05 Facility Permit No. Reporting Period Station Date Loaded Zip File Name Byesville Aseptics LLC * 0DP00003*EP August 2005 2 9/14/05 10:00 AM 1424331.ZIP August 2005:0DP00003002 G & J Pepsi-Cola Franklin Furnace 0DP00008*DP 1 9/29/05 4:56 PM TCL07Y05.zip Jan05-Jun05:0DP00008001 MFM Building Products Corp 0GN00009*AG September 2005 1 9/29/05 9:06 AM 15394975.ZIP September 2005:0GN00009001 Valley View Inn 0GS00005*BG July 2005 3 9/2/05 10:03 AM July 2005:0GS00005003 McConnelsville Duchess 0GU00034*AG August 2005 1 9/20/05 11:47 AM 16405597.ZIP August 2005:0GU00034001 Buffalo Starfire 0GU00037*AG July 2005 1 9/2/05 10:07 AM July 2005:0GU00037001 Buffalo Starfire 0GU00037*AG August 2005 1 9/29/05 9:18 AM M8G07Y05.zip August 2005:0GU00037001 Working Man's Friend 0GU00038*AG July 2005 1 9/2/05 10:06 AM July 2005:0GU00038001 Ohio Oil Gathering Corp 0GV00003*AG July 2005 1 9/2/05 10:02 AM July 2005:0GV00003001 Ohio Oil Gathering Corp 0GV00003*AG August 2005 1 9/29/05 9:18 AM M8G07Y05.zip August 2005:0GV00003001 Dogwood Lane Apartments 0GV00006*AG August 2005 1 9/29/05 9:18 AM M8G07Y05.zip August 2005:0GV00006001 MW Custom Papers LLC 0IA00002*HD July 2005 1 9/22/05 12:57 PM 13251812.ZIP July 2005:0IA00002001 MW Custom Papers LLC 0IA00002*HD July 2005 582 9/22/05 12:57 PM 13251812.ZIP July 2005:0IA00002582 MW Custom Papers LLC 0IA00002*HD July 2005 586 9/22/05 12:57 PM 13251812.ZIP July 2005:0IA00002586 MW Custom Papers LLC 0IA00002*HD July 2005 600 9/22/05 12:57 PM 13251812.ZIP July 2005:0IA00002600 MW Custom Papers LLC -

Scouting in Ohio

Scouting Ohio! Sipp-O Lodge’s Where to Go Camping Guide Written and Published by Sipp-O Lodge #377 Buckeye Council, Inc. B.S.A. 2009 Introduction This book is provided as a reference source. The information herein should not be taken as the Gospel truth. Call ahead and obtain up-to-date information from the place you want to visit. Things change, nothing is guaranteed. All information and prices in this book were current as of the time of publication. If you find anything wrong with this book or want something added, tell us! Sipp-O Lodge Contact Information Mail: Sipp-O Lodge #377 c/o Buckeye Council, Inc. B.S.A. 2301 13th Street, NW Canton, Ohio 44708 Phone: 330.580.4272 800.589.9812 Fax: 330.580.4283 E-Mail: [email protected] [email protected] Homepage: http://www.buckeyecouncil.org/Order%20of%20the%20Arrow.htm Table of Contents Scout Camps Buckeye Council BSA Camps ............................................................ 1 Seven Ranges Scout Reservation ................................................ 1 Camp McKinley .......................................................................... 5 Camp Rodman ........................................................................... 9 Other Councils in Ohio .................................................................... 11 High Adventure Camps .................................................................... 14 Other Area Camps Buckeye .......................................................................................... 15 Pee-Wee .........................................................................................