The Evolution of the Louis Bromfield Sustainable Agriculture Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saving the Dust Bowl: “Big Hugh” Bennett’S Triumph Over Tragedy

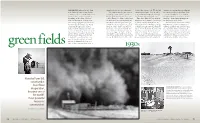

Saving the Dust Bowl: “Big Hugh” Bennett’s Triumph over Tragedy Rebecca Smith Senior Historical Paper “It was dry everywhere . and there was entirely too much dust.” -Hugh Hammond Bennett, visit to the Dust Bowl, 19361 Merciless winds tore up the soil that once gave the Southern Great Plains life and hurled it in roaring black clouds across the nation. Hopelessly indebted farmers fed tumbleweed to their cattle, and, in the case of one Oklahoma town, to their children. By the 1930s, years of injudicious cultivation had devastated 100 million acres of Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, Colorado, and New Mexico.2 This was the Dust Bowl, and it exposed a problem that had silently plagued American agriculture for centuries–soil erosion. Farmers, scientists, and the government alike considered it trivial until Hugh Hammond Bennett spearheaded a national program of soil conservation. “The end in view,” he proclaimed, “is that people everywhere will understand . the obligation of respecting the earth and protecting it in order that they may enjoy its fullness.” 3 Because of his leadership, enthusiasm, and intuitive understanding of the American farmer, Bennett triumphed over the tragedy of the Dust Bowl and the ignorance that caused it. Through the Soil Conservation Service, Bennett reclaimed the Southern Plains, reformed agriculture’s philosophy, and instituted a national policy of soil conservation that continues today. The Dust Bowl tragedy developed from the carelessness of plenty. In the 1800s, government and commercial promotions encouraged negligent settlement of the Plains, lauding 1 Hugh Hammond Bennett, Soil Conservation in the Plains Country, TD of address for Greater North Dakota Association and Fargo Chamber of Commerce Banquet, Fargo, ND., 26 Jan. -

Hugh Hammond Bennett

Hugh Hammond Bennett nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/national/about/history/ "Father of Soil Conservation" Hugh Hammond Bennett (April 15 1881-7 July 1960) was born near Wadesboro in Anson County, North Carolina, the son of William Osborne Bennett and Rosa May Hammond, farmers. Bennett earned a bachelor of science degree an emphasis in chemistry and geology from the University of North Carolina in June 1903. At that time, the Bureau of Soils within the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) had just begun to make county-based soil surveys, which would in the time be regarded as important American contributions to soil science. Bennett accepted a job in the bureau headquarters' laboratory in Washington, D.C., but agreed first to assist on the soil survey of Davidson County, Tennessee, beginning 1 July 1903. The acceptance of that task, in Bennett's words, "fixed my life's work in soils." The outdoor work suited Bennett, and he compiled a number of soil surveys. The 1905 survey of Louisa County, Virginia, in particular, profoundly affected Bennett. He had been directed to the county to investigate its reputation of declining crop yields. As he compared virgin, timbered sites to eroded fields, he became convinced that soil erosion was a problem not just for the individual farmer but also for rural economies. While this experience aroused his curiosity, it was, according to Bennett's recollection shortly before his death, Thomas C. Chamberlain's paper on "Soil Wastage" presented in 1908 at the Governors Conference in the White House (published in Conference of Governors on Conservation of Natural Resources, ed. -

“Garden-Magic”: Conceptions of Nature in Edith Wharton's Fiction

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2021 “Garden-Magic”: Conceptions of Nature in Edith Wharton’s Fiction Jonathan Malks Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, American Literature Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, Other Environmental Sciences Commons, Theory and Philosophy Commons, United States History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Malks, Jonathan, "“Garden-Magic”: Conceptions of Nature in Edith Wharton’s Fiction" (2021). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1603. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1603 This Honors Thesis -- Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Malks 1 “Garden-Magic”: Conceptions of Nature in Edith Wharton’s Fiction A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in English from William & Mary by Jonathan M. Malks Accepted for Honors ________________________________________ Melanie V. Dawson, Thesis Advisor Elizabeth Barnes ________________________________________ Elizabeth Barnes, Exam Chair ________________________________________ Alan C. Braddock Francesca Sawaya ________________________________________ Francesca Sawaya Williamsburg, VA May 12, 2021 Malks 2 Land’s End It’s strangely balmy for November. I feel the heat and pluck a noxious red soda apple off of its brown and thorny stem. Many people here are bent on keeping “unwanteds” out, but these weeds grow ferally. They go without direction, and you can’t restrain them with a rusty, old “no photo” sign. -

Notes on Contributors 7 6 7

NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS 7 6 7 NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS ALLEN, Walter. Novelist and Literary Critic. Author of six novels (the most recent being All in a Lifetime, 1959); several critical works, including Arnold Bennett, 1948; Reading a Novel, 1949 (revised, 1956); Joyce Cary, 1953 (revised, 1971); The English Novel, 1954; Six Great Novelists, 1955; The Novel Today, 1955 (revised, 1966); George Eliot, 1964; and The Modern Novel in Britain and the United States, 1964; and of travel books, social history, and books for children. Editor of Writers on Writing, 1948, and of The Roaring Queen by Wyndham Lewis, 1973. Has taught at several universities in Britain, the United States, and Canada, and been an editor of the New Statesman. Essays: Richard Hughes; Ring Lardner; Dorothy Richardson; H. G. Wells. ANDERSON, David D. Professor of American Thought and Language, Michigan State University, East Lansing; Editor of University College Quarterly and Midamerica. Author of Louis Bromfield, 1964; Critical Studies in American Literature, 1964; Sherwood Anderson, 1967; Anderson's "Winesburg, Ohio," 1967; Brand Whitlock, 1968; Abraham Lincoln, 1970; Robert Ingersoll, 1972; Woodrow Wilson, 1975. Editor or Co-Editor of The Black Experience, 1969; The Literary Works of Lincoln, 1970; The Dark and Tangled Path, 1971 ; Sunshine and Smoke, 1971. Essay: Louis Bromfield. ANGLE, James. Assistant Professor of English, Eastern Michigan University, Ypsilanti. Author of verse and fiction in periodicals, and of an article on Edward Lewis Wallant in Kansas Quarterly, Fall 1975. Essay: Edward Lewis Wallant. ASHLEY, Leonard R.N. Professor of English, Brooklyn College, City University of New York. Author of Colley Cibber, 1965; 19th-Century British Drama, 1967; Authorship and Evidence: A Study of Attribution and the Renaissance Drama, 1968; History of the Short Story, 1968; George Peele: The Man and His Work, 1970. -

The Celebrating Ohio Book Awards & Authors

The Celebrating Ohio Book Awards & Authors (COBAA) grant provides federal LSTA funds specifically for collection development purposes, connecting Ohio readers to Ohio authors and Ohio book award winners. For more information about the grant and the application process, visit the State Library of Ohio website at: https://library.ohio.gov/services-for-libraries/lsta-grants/ This Excel workbook includes a complete list of over 1,000 COBAA grant eligible titles from the following awards and book lists: Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards Buckeye Children’s and Teen Book Awards Choose to Read Ohio Book List Dayton Literary Peace Prize Floyd’s Pick Book Award James Cook Book Award Norman A. Sugarman Children’s Biography Award Ohioana Book Awards Thurber Prize for American Humor Questions should be addressed to LSTA Coordinator, Cindy Boyden, via [email protected] State Library of Ohio library.ohio.gov 1 Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards Awarded annually in September Nonfiction Award Year Winner or Finalist Author Name Title Genre 2020 Winner King, Charles Gods of the Upper Air Nonfiction Delbanco, 2019 Winner Andrew The War Before The War Nonfiction Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, 2018 Winner Young, Kevin Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News Nonfiction Shetterly, 2017 Winner Margot Lee Hidden Figures Nonfiction Faderman, 2016 Winner Lillian The Gay Revolution: The Story of the Struggle Nonfiction 2016 Winner Seibert, Brian What the Eye Hears: A History of Tap Dancing Nonfiction 2014 Winner Shavit, Ari My Promised Land Nonfiction American Oracle: -

Forest History Today Spring/Fall 2014

A PUBLICATION OF THE FOREST HISTORY SOCIETY SPRING/FALL 2014 VOL. 20, NOS. 1 & 2 MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT “Not everybody trusts paintings but people believe photographs.”–Ansel Adams STEVEN ANDERSON hen Gifford Pinchot hired the first come from both the FHS Photograph Collec - forest rangers in the U.S. Forest tion and from institutional and individual col- WService, he outfitted them with cam- laborators. By providing an authoritative site eras and asked them to document what they did on the subject, we expect to identify previously and saw. He knew the power the photographs unknown repeat photographic pairs and could wield as he fought for funds to manage sequences, promote the creation of new repeat the nation’s forests and sought public support sets, and foster interest in the future uses of for new policies. No one can deny that visual repeat photography. images have played an important role in the con- Sally Mann, a renowned American landscape servation and environmental movements. and portrait photographer, said, “Photographs That is why, from its beginnings in 1946, the open doors into the past, but they also allow a Forest History Society has collected and pre- look into the future.” We hope that providing served photographs of early lumbering tech- access to and stimulating more work in repeat niques, forest products, forest management, photography will help students, teachers, jour- and other subjects. The FHS staff has already helped thousands nalists, foresters, and many others gain insight that can elevate of students, writers, and scholars find historic photographs that our awareness of conservation challenges. -

How the Farm Bill, Conceived in Dust Bowl Desperation, Became One Of

IT WAS THE 1930S, and rural people clung sugarbeet, dust rose to meet their gaze. because there was no feed. We also had extensive root systems that can withstand to the land as if it were a part of them, “The dust storms, they just come in a grasshopper plague. There would be the extreme weather on the plains. While as integral as bone or sinew. But the land boiling like angry clouds,” remembers so many flying, they would darken the a nine-year drought has been dragging betrayed them—or they betrayed it, Maxine Nickelson, 81, who lives near sun. It was really, really hard times.” the region by the heels, farmers—and the depending on the telling of history. Oakley, Kansas, less than 10 miles from Times have changed. Now, when the landscape—aren’t facing anything near In the black-and-white portraits of the the farm where she grew up during the wind blows at The Nature Conservancy’s the desperation of the 1930s. time, dismay is palpable, grooves of anx- Dust Bowl. “The dust piles would get 17,000-acre Smoky Valley Ranch, 15 That the country hasn’t seen another iety worn deep around the eyes. In scat- so high they’d cover up the fence posts miles south of where Nickelson grew up, Dust Bowl is testament to advances in tered fields throughout the country, along the roads. Yeah, it was bad. We it whispers through a thriving shortgrass farming equipment and cultivation prac- farmers took the stitching out of the soil had to use a scoop shovel to take dirt prairie. -

Pulitzer Prize

1946: no award given 1945: A Bell for Adano by John Hersey 1944: Journey in the Dark by Martin Flavin 1943: Dragon's Teeth by Upton Sinclair Pulitzer 1942: In This Our Life by Ellen Glasgow 1941: no award given 1940: The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck 1939: The Yearling by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Prize-Winning 1938: The Late George Apley by John Phillips Marquand 1937: Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell 1936: Honey in the Horn by Harold L. Davis Fiction 1935: Now in November by Josephine Winslow Johnson 1934: Lamb in His Bosom by Caroline Miller 1933: The Store by Thomas Sigismund Stribling 1932: The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck 1931 : Years of Grace by Margaret Ayer Barnes 1930: Laughing Boy by Oliver La Farge 1929: Scarlet Sister Mary by Julia Peterkin 1928: The Bridge of San Luis Rey by Thornton Wilder 1927: Early Autumn by Louis Bromfield 1926: Arrowsmith by Sinclair Lewis (declined prize) 1925: So Big! by Edna Ferber 1924: The Able McLaughlins by Margaret Wilson 1923: One of Ours by Willa Cather 1922: Alice Adams by Booth Tarkington 1921: The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton 1920: no award given 1919: The Magnificent Ambersons by Booth Tarkington 1918: His Family by Ernest Poole Deer Park Public Library 44 Lake Avenue Deer Park, NY 11729 (631) 586-3000 2012: no award given 1980: The Executioner's Song by Norman Mailer 2011: Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 1979: The Stories of John Cheever by John Cheever 2010: Tinkers by Paul Harding 1978: Elbow Room by James Alan McPherson 2009: Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 1977: No award given 2008: The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 1976: Humboldt's Gift by Saul Bellow 2007: The Road by Cormac McCarthy 1975: The Killer Angels by Michael Shaara 2006: March by Geraldine Brooks 1974: No award given 2005: Gilead by Marilynne Robinson 1973: The Optimist's Daughter by Eudora Welty 2004: The Known World by Edward P. -

Iowa Soil and Water Conservation Commissioner Handbook

IOWA SOIL AND WATER CONSERVATION COMMISSIONER HANDBOOK Written in joint cooperation by: • Conservation Districts of Iowa • Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship - Division of Soil Conservation and Water Quality • Natural Resources Conservation Service Revised: 12.15.2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Topic Page Preface 3 History and Development of Soil and Water Conservation Districts 4 Organization of Soil and Water Conservation Districts Under State Law 6 The District Board 10 District Administration 14 District Plans and Planning Activities 19 Commissioner Development and Training 22 Partner Agencies and Organizations Working with Districts 23 Legal and Ethical Issues 29 Appendix A: Acronyms 32 Appendix B: References and Resources 34 Appendix C: Sediment Control Law 35 Appendix D: Map of CDI Regions 36 Appendix E: Map of IDALS Field Representative Areas 37 Appendix F: Map of NRCS Areas 38 Appendix G: Financial Checklist 39 Appendix H: Financial Policies Annual Checklist 40 2 PREFACE Congratulations upon election to your local Soil and Water Conservation District Board and welcome to your role as a Soil and Water Conservation District Commissioner in the State of Iowa. As a Commissioner, you are a locally elected conservation leader; understanding your role and responsibilities as a Commissioner will assist you to effectively promote and implement conservation in your community. This Iowa Soil and Water Conservation District Commissioner Handbook provides you with an orientation to your role and responsibilities. Every effort has been made to make this handbook beneficial. Please note that this handbook is a basic resource for commissioners. The general statement of powers, duties, and specific provisions of the Conservation Districts are contained in Iowa Code Chapter 161A. -

Readings in the History of the Soil Conservation Service

United States Department of Agriculture Readings in the Soil Conservation Service History of the Soil Conservation Service Economics and Social Sciences Division, NHQ Historical Notes Number 1 Introduction The articles in this volume relate in one way or another to the history of the Soil Conservation Service. Collectively, the articles do not constitute a comprehensive history of SCS, but do give some sense of the breadth and diversity of SCS's missions and operations. They range from articles published in scholarly journals to items such as "Soil Conservation: A Historical Note," which has been distributed internally as a means of briefly explaining the administrative and legislative history of SCS. To answer reference requests I have made reprints of the published articles and periodically made copies of some of the unpublished items. Having the materials together in a volume is a very convenient way to satisfy these requests in a timely manner. Also, since some of these articles were distributed to SCS field offices, many new employees have joined the Service. I wanted to take the opportunity to reach them. SCS employees are the main audience. We have produced this volume in the rather unadorned and inexpensive manner so that we can distribute the volume widely and have it available for training sessions and other purposes. Also we can readily add articles in the future. If anyone should wish to quote or cite any of the published articles, please use the citations provided at the beginning of the article. For other articles please cite this publication. Steven Phillips, a graduate student in history at Georgetown University and a 1992 summer intern here with SCS, converted the articles to this uniform format, and is hereby thanked for his very professional efforts. -

THE WALTER STANLEY CAMPBELL COLLECTION Inventory and Index

THE WALTER STANLEY CAMPBELL COLLECTION Inventory and Index Revised and edited by Kristina L. Southwell Associates of the Western History Collections Norman, Oklahoma 2001 Boxes 104 through 121 of this collection are available online at the University of Oklahoma Libraries website. THE COVER Michelle Corona-Allen of the University of Oklahoma Communication Services designed the cover of this book. The three photographs feature images closely associated with Walter Stanley Campbell and his research on Native American history and culture. From left to right, the first photograph shows a ledger drawing by Sioux chief White Bull that depicts him capturing two horses from a camp in 1876. The second image is of Walter Stanley Campbell talking with White Bull in the early 1930s. Campbell’s oral interviews of prominent Indians during 1928-1932 formed the basis of some of his most respected books on Indian history. The third photograph is of another White Bull ledger drawing in which he is shown taking horses from General Terry’s advancing column at the Little Big Horn River, Montana, 1876. Of this act, White Bull stated, “This made my name known, taken from those coming below, soldiers and Crows were camped there.” Available from University of Oklahoma Western History Collections 630 Parrington Oval, Room 452 Norman, Oklahoma 73019 No state-appropriated funds were used to publish this guide. It was published entirely with funds provided by the Associates of the Western History Collections and other private donors. The Associates of the Western History Collections is a support group dedicated to helping the Western History Collections maintain its national and international reputation for research excellence. -

Shepard - Coming Home to the Pleistocene.Pdf

Coming Home to the Pleistocene Paul Shepard Edited by Florence R. Shepard ISLAND PRESS / Shearwater Books Washington, D.C. • Covelo, California A Shearwater Book published by Island Press Copyright © 1998 Florence Shepard All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher: Island Press, 1718 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 300, Washington, DC 20009. Shearwater Books is a trademark of The Center for Resource Economics. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Shepard, Paul, 1925–1996 Coming home to the Pleistocene / Paul Shepard ; edited by Florence R. Shepard. p. cm. “A Shearwater book”— Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1–55963–589–4. — ISBN 1–55963–590–8 1. Hunting and gathering societies. 2. Sociobiology. 3. Nature and nurture. I. Shepard, Florence R. II. Title. GN388.S5 1998 98-8074 306.3’64—dc21 CIP Printed on recycled, acid-free paper Manufactured in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Preface ix Introduction 1 I. The Relevance of the Past 7 Our Pleistocene ancestors and contemporary hunter/gatherers cannot be under- stood in a historical context that, as a chronicle of linear events, has distorted the meaning of the “savage” in us. II. Getting a Genome 19 Being human means having evolved—especially with respect to a special past in open country, where the basic features that make us human came into being. Coming down out of the trees, standing on our own two feet, freed our hands and brought a perceptual vision never before seen on the planet.