Forest History Today Spring/Fall 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mark Your Calendar

MARK YOUR CALENDAR OLD FORESTS, NEW MANAGEMENT: CANADIAN INSTITUTE OF FORESTRY–100TH ANNUAL CONSERVATION AND USE OF OLD-GROWTH FORESTS GENERAL MEETING AND CONFERENCE IN THE 21ST CENTURY September 7–10, 2008. Fredericton, New Brunswick. Contact: February 17–21, 2008. Hobart, Tasmania, Australia. An interna- CIF, 151 Slater Street, Suite 504 Ottawa, ON K1P 5H3; Phone: tional scientific conference hosted by the CRC for Forestry, 613-234-2242; Fax: 613-234-6181; [email protected]; http://www.cif- Forestry Tasmania, and the International Union of Forest ifc.org/english/e-agms.shtml. Research Organizations. Contact: Conference Design, Sandy Bay Tasmania 7006, Australia; Phone: +61 03 6224 3773; SOCIETY OF AMERICAN FORESTERS [email protected]; www.cdesign.com.au/oldforests2008/. NATIONAL CONVENTION November 5–9, 2008. Reno, Nevada. Contact: William V. Brumby, ASSOCIATION OF BRITISH COLUMBIA FOREST Society of American Foresters; Phone: 301-897-8720, ext. 129; PROFESSIONALS CONFERENCE AND ANNUAL GENERAL [email protected]; www.safnet.org. MEETING February 20–22, 2008. Penticton, British Columbia. Theme: “Facets AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY of Our Future Forests.” Contact: ExpoFor 2008, Association of ANNUAL MEETING BC Forest Professionals, 1030–1188 West Georgia Street, Vancouver, February 25–March 1, 2009. Tallahassee, Florida. Contact: Fritz BC V6E 4A2. Phone: 604-687-8027; Fax: 604-687-3264; info@expo- Davis, local arrangements chair, at [email protected]; www.aseh.net/ for.ca; http://www.expofor.ca/contactus/contactus.htm. conferences. AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY FIRST WORLD ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY CONVENTION ANNUAL MEETING August 4–9, 2009. Copenhagen, Denmark. Sponsored by the March 12–16, 2008. -

Saving the Dust Bowl: “Big Hugh” Bennett’S Triumph Over Tragedy

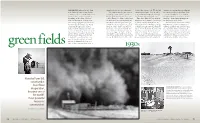

Saving the Dust Bowl: “Big Hugh” Bennett’s Triumph over Tragedy Rebecca Smith Senior Historical Paper “It was dry everywhere . and there was entirely too much dust.” -Hugh Hammond Bennett, visit to the Dust Bowl, 19361 Merciless winds tore up the soil that once gave the Southern Great Plains life and hurled it in roaring black clouds across the nation. Hopelessly indebted farmers fed tumbleweed to their cattle, and, in the case of one Oklahoma town, to their children. By the 1930s, years of injudicious cultivation had devastated 100 million acres of Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, Colorado, and New Mexico.2 This was the Dust Bowl, and it exposed a problem that had silently plagued American agriculture for centuries–soil erosion. Farmers, scientists, and the government alike considered it trivial until Hugh Hammond Bennett spearheaded a national program of soil conservation. “The end in view,” he proclaimed, “is that people everywhere will understand . the obligation of respecting the earth and protecting it in order that they may enjoy its fullness.” 3 Because of his leadership, enthusiasm, and intuitive understanding of the American farmer, Bennett triumphed over the tragedy of the Dust Bowl and the ignorance that caused it. Through the Soil Conservation Service, Bennett reclaimed the Southern Plains, reformed agriculture’s philosophy, and instituted a national policy of soil conservation that continues today. The Dust Bowl tragedy developed from the carelessness of plenty. In the 1800s, government and commercial promotions encouraged negligent settlement of the Plains, lauding 1 Hugh Hammond Bennett, Soil Conservation in the Plains Country, TD of address for Greater North Dakota Association and Fargo Chamber of Commerce Banquet, Fargo, ND., 26 Jan. -

Three Days' Forest Festival on the Biltmore Estate

DECEMBER 5, 1908 AMERICAN LUMBERMAN. 35 THREE DAYS’ FOREST FESTIVAL ON THE BILTMORE ESTATE. --------------------------------------- Extraordinary Outing of Representatives of All Concerned With Timber From the Tree to the Trade—Biltmore Estate, the Property of George W. Vanderbilt, Used Educationally in a Unique Celebration Under the Direction of C. A. Schenck, Ph. D.—Authorities Invade the Woods for Lectures by the Master Forester—Openhanded, Open Air Hospitality—Anniver= saries Signalized in an Unprecedented Way—Beauti= ful Biltmore in Story and Verse. --------------------------------------- known as the Biltmore estate. The invitations, eagerly milling operations and surveying. They enter practically BILTMORE. accepted, brought to Asheville, N.C., of which Biltmore is a into the various methods of timber estimating, including suburb, many of the country’s best known to professional the strip method, the “forty” method and Schenck’s We are but borrowers of God’s good soil, and business life as directly or indirectly interested in any method, and for ten continuous days they estimate on phase of timber growth, from its inauguration and some tract to be cut for an estate mill. Here they endure Free tenants of His field and vale and hill; preservation to its commercial utilization. These and the all he hardships of a timber estimator’s life; working We are but workmen ‘mid his vines to toil multitude of others who will be interested in these eight hours a day, cooking their own meals and sleeping To serve his purpose and obey His will. chronicles of the recent forest festival will be glad to learn in the open rolled up in blankets. -

Hugh Hammond Bennett

Hugh Hammond Bennett nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/national/about/history/ "Father of Soil Conservation" Hugh Hammond Bennett (April 15 1881-7 July 1960) was born near Wadesboro in Anson County, North Carolina, the son of William Osborne Bennett and Rosa May Hammond, farmers. Bennett earned a bachelor of science degree an emphasis in chemistry and geology from the University of North Carolina in June 1903. At that time, the Bureau of Soils within the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) had just begun to make county-based soil surveys, which would in the time be regarded as important American contributions to soil science. Bennett accepted a job in the bureau headquarters' laboratory in Washington, D.C., but agreed first to assist on the soil survey of Davidson County, Tennessee, beginning 1 July 1903. The acceptance of that task, in Bennett's words, "fixed my life's work in soils." The outdoor work suited Bennett, and he compiled a number of soil surveys. The 1905 survey of Louisa County, Virginia, in particular, profoundly affected Bennett. He had been directed to the county to investigate its reputation of declining crop yields. As he compared virgin, timbered sites to eroded fields, he became convinced that soil erosion was a problem not just for the individual farmer but also for rural economies. While this experience aroused his curiosity, it was, according to Bennett's recollection shortly before his death, Thomas C. Chamberlain's paper on "Soil Wastage" presented in 1908 at the Governors Conference in the White House (published in Conference of Governors on Conservation of Natural Resources, ed. -

Forestry Education at the University of California: the First Fifty Years

fORESTRY EDUCRTIOfl T THE UflIVERSITY Of CALIFORflffl The first fifty Years PAUL CASAMAJOR, Editor Published by the California Alumni Foresters Berkeley, California 1965 fOEUJOD T1HEhistory of an educational institution is peculiarly that of the men who made it and of the men it has helped tomake. This books tells the story of the School of Forestry at the University of California in such terms. The end of the first 50 years oi forestry education at Berkeley pro ides a unique moment to look back at what has beenachieved. A remarkable number of those who occupied key roles in establishing the forestry cur- riculum are with us today to throw the light of personal recollection and insight on these five decades. In addition, time has already given perspective to the accomplishments of many graduates. The School owes much to the California Alumni Foresters Association for their interest in seizing this opportunity. Without the initiative and sustained effort that the alunmi gave to the task, the opportunity would have been lost and the School would have been denied a valuable recapitulation of its past. Although this book is called a history, this name may be both unfair and misleading. If it were about an individual instead of an institution it might better be called a personal memoir. Those who have been most con- cerned with the task of writing it have perhaps been too close to the School to provide objective history. But if anything is lost on this score, it is more than regained by the personalized nature of the account. -

The Shelterbelt “Scheme”: Radical Ecological Forestry and the Production Of

The Shelterbelt “Scheme”: Radical Ecological Forestry and the Production of Climate in the Fight for the Prairie States Forestry Project A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY MEAGAN ANNE SNOW IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. Roderick Squires January 2019 © Meagan A. Snow 2019 Acknowledgements From start to finish, my graduate career is more than a decade in the making and getting from one end to the other has been not merely an academic exercise, but also one of finding my footing in the world. I am thankful for the challenge of an ever-evolving committee membership at the University of Minnesota’s Geography Department that has afforded me the privilege of working with a diverse set of minds and personalities: thank you Karen Till, Eric Sheppard, Richa Nagar, Francis Harvey, and Valentine Cadieux for your mentorship along the way, and to Kate Derickson, Steve Manson, and Peter Calow for stepping in and graciously helping me finish this journey. Thanks also belong to Kathy Klink for always listening, and to John Fraser Hart, an unexpected ally when I needed one the most. Matthew Sparke and the University of Washington Geography Department inspired in me a love of geography as an undergraduate student and I thank them for making this path possible. Thank you is also owed to the Minnesota Population Center and the American University Library for employing me in such good cheer. Most of all, thank you to Rod Squires - for trusting me, for appreciating my spirit and matching it with your own, and for believing I am capable. -

Biltmore Forest School Reunion, May 29,1950 Mr

“Flowers for the Living” A Tribute to a Master By Inman F. Eldredge Biltmore ‘06 Carl Alvin Schenck, the forester, the teacher, and, even more, the personality, made a place in my mind and in my heart that has grown even deeper and warmer as the years of my life have ripened. From that day in Sep- tember, 1904, when I came up, a gay young sprout, from the sand hills of South Carolina to join the Biltmore Forest School, to this at the quiet end of my forestry career, no man has quite supplanted him in affection and respect. I knew him, as did most of his "boys," when he was at his brilliant best; bold in thought, colorful in word and phrase, and so damned energetic in action that he kept two horses, three dogs and all of his pupils winded and heaving six days out of the week. There was never a dull hour either in class or in the woods. He knew his subject as did no other man in America and had, to a truly remarkable degree, a happy ability to reach and guide our groping minds without apparent effort. Full and broad as was the knowledge he imparted from a rich background of training and experience his teaching was not confined to class room lectures and hillside demonstrations. Some of the things I learned at Biltmore would be hard to find in any text book published then or later— things, that as I look back over my 44 years as a forester, have proved fully as potent for good as any of the technical disciplines of the profession. -

How the Farm Bill, Conceived in Dust Bowl Desperation, Became One Of

IT WAS THE 1930S, and rural people clung sugarbeet, dust rose to meet their gaze. because there was no feed. We also had extensive root systems that can withstand to the land as if it were a part of them, “The dust storms, they just come in a grasshopper plague. There would be the extreme weather on the plains. While as integral as bone or sinew. But the land boiling like angry clouds,” remembers so many flying, they would darken the a nine-year drought has been dragging betrayed them—or they betrayed it, Maxine Nickelson, 81, who lives near sun. It was really, really hard times.” the region by the heels, farmers—and the depending on the telling of history. Oakley, Kansas, less than 10 miles from Times have changed. Now, when the landscape—aren’t facing anything near In the black-and-white portraits of the the farm where she grew up during the wind blows at The Nature Conservancy’s the desperation of the 1930s. time, dismay is palpable, grooves of anx- Dust Bowl. “The dust piles would get 17,000-acre Smoky Valley Ranch, 15 That the country hasn’t seen another iety worn deep around the eyes. In scat- so high they’d cover up the fence posts miles south of where Nickelson grew up, Dust Bowl is testament to advances in tered fields throughout the country, along the roads. Yeah, it was bad. We it whispers through a thriving shortgrass farming equipment and cultivation prac- farmers took the stitching out of the soil had to use a scoop shovel to take dirt prairie. -

The American Tree Farm System Celebrated Its 70Th Anniversary

In 2011, the American Tree Farm System celebrated its 70th anniversary. After a controversial beginning, it is now an important player in efforts to mitigate climate change. The American Tree Farm System GROWING STEWARDSHIP FROM THE ROOTS “ ill the thing before it spreads,” U.S. Forest Service Chief Lyle Watts allegedly declared. Watts and his assistant C. Edward Behre tried to kill the thing in K 1941. They failed, and it spread from the West, into the South, and eventually all across America. The “thing” was the American Tree Farm System (ATFS), which is now 71 years old and America’s oldest family-owned federal regulation is certainly not to its discredit,” according to woodland sustainability program, covering more than 26 million the journal. privately owned acres. Why were Watts and Behre against tree farms in 1941? PUSH FOR FEDERAL REGULATION Encouraging private owners to grow continuous crops of trees The strong push for federal regulation of forestry had begun in (as tree farming was defined) probably was not abhorrent to them. the 1930s, during America’s Great Depression. Federal forestry What they disliked was substituting private cooperation for public leaders believed that they should closely regulate the private sector, regulation. They saw tree farming as a move to decrease pressure and many people agreed. The National Industrial Recovery Act for federal regulation. of 1933, for example, had authority to coordinate major industries Watts and Behre asked the Society of American Foresters to to set prices, working conditions, and (in the case of forest indus- question the ethics of members who participated in tree farming. -

Iowa Soil and Water Conservation Commissioner Handbook

IOWA SOIL AND WATER CONSERVATION COMMISSIONER HANDBOOK Written in joint cooperation by: • Conservation Districts of Iowa • Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship - Division of Soil Conservation and Water Quality • Natural Resources Conservation Service Revised: 12.15.2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Topic Page Preface 3 History and Development of Soil and Water Conservation Districts 4 Organization of Soil and Water Conservation Districts Under State Law 6 The District Board 10 District Administration 14 District Plans and Planning Activities 19 Commissioner Development and Training 22 Partner Agencies and Organizations Working with Districts 23 Legal and Ethical Issues 29 Appendix A: Acronyms 32 Appendix B: References and Resources 34 Appendix C: Sediment Control Law 35 Appendix D: Map of CDI Regions 36 Appendix E: Map of IDALS Field Representative Areas 37 Appendix F: Map of NRCS Areas 38 Appendix G: Financial Checklist 39 Appendix H: Financial Policies Annual Checklist 40 2 PREFACE Congratulations upon election to your local Soil and Water Conservation District Board and welcome to your role as a Soil and Water Conservation District Commissioner in the State of Iowa. As a Commissioner, you are a locally elected conservation leader; understanding your role and responsibilities as a Commissioner will assist you to effectively promote and implement conservation in your community. This Iowa Soil and Water Conservation District Commissioner Handbook provides you with an orientation to your role and responsibilities. Every effort has been made to make this handbook beneficial. Please note that this handbook is a basic resource for commissioners. The general statement of powers, duties, and specific provisions of the Conservation Districts are contained in Iowa Code Chapter 161A. -

Publications of the Forest History Society

Publications of the Forest History Society These are books and films available from the Forest History Society The Forest Service and the Greatest Good: A Centennial History, on our website at www.ForestHistory.org/Publications. James G. Lewis, paper $20.00 Tongass Timber: A History of Logging and Timber Utilization in Southeast From THE FOREST HISTORY SOCIETY Alaska, James Mackovjak, $19.95 Issues Series—$9.95 each View From the Top: Forest Service Research, R. Keith Arnold, Books in the Issues Series bring a historical context to today’s most pressing M. B. Dickerman, Robert E. Buckman, $13.00 issues in forestry and natural resource management. These introductory texts are created for a general audience. With DUKE UNIVERSITY PRESS Changing Pacific Forests: Historical Perspectives on the Forest Economy of the Pacific Basin America’s Fires: A Historical Context for Policy and Practice, Stephen J. Pyne , John Dargavel and Richard Tucker, paper $5.00 David T. Mason: Forestry Advocate America’s Forested Wetlands: From Wasteland to Valued Resource, , Elmo Richardson, $8.00 Bernhard Eduard Fernow: A Story of North American Forestry Jeffrey K. Stine , American Forests: A History of Resiliency and Recovery, Andrew Denny Rodgers III, $5.00 Origins of the National Forests: A Centennial Symposium Douglas W. MacCleery , Canada’s Forests: A History, Ken Drushka Harold K. Steen, cloth $10.00, paper $5.00 Changing Tropical Forests: Historical Perspectives on Today’s Challenges in Forest Pharmacy: Medicinal Plants in American Forests, Steven Foster Central and South America Forest Sustainability: The History, the Challenge, the Promise, , Harold K. Steen and Richard P. -

Readings in the History of the Soil Conservation Service

United States Department of Agriculture Readings in the Soil Conservation Service History of the Soil Conservation Service Economics and Social Sciences Division, NHQ Historical Notes Number 1 Introduction The articles in this volume relate in one way or another to the history of the Soil Conservation Service. Collectively, the articles do not constitute a comprehensive history of SCS, but do give some sense of the breadth and diversity of SCS's missions and operations. They range from articles published in scholarly journals to items such as "Soil Conservation: A Historical Note," which has been distributed internally as a means of briefly explaining the administrative and legislative history of SCS. To answer reference requests I have made reprints of the published articles and periodically made copies of some of the unpublished items. Having the materials together in a volume is a very convenient way to satisfy these requests in a timely manner. Also, since some of these articles were distributed to SCS field offices, many new employees have joined the Service. I wanted to take the opportunity to reach them. SCS employees are the main audience. We have produced this volume in the rather unadorned and inexpensive manner so that we can distribute the volume widely and have it available for training sessions and other purposes. Also we can readily add articles in the future. If anyone should wish to quote or cite any of the published articles, please use the citations provided at the beginning of the article. For other articles please cite this publication. Steven Phillips, a graduate student in history at Georgetown University and a 1992 summer intern here with SCS, converted the articles to this uniform format, and is hereby thanked for his very professional efforts.