A Changing Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religion and Museums: Immaterial and Material Heritage

RELIGION AND MUSEUMS RELIGION RELIGION AND MUSEUMS The relation between religion and museum is particularly fertile and needs an organic, courageous and interdisciplinary Immaterial and Material Heritage reflection. An established tradition of a religion museology - EDITED BY let alone a religion museography - does not exist as yet, as well VALERIAMINUCCIANI as a project coordinated at European level able to coagulate very different disciplinary skills, or to lay the foundations for a museums’ Atlas related to this theme. Our intention was to investigate the reasons as well as the ways in which religion is addressed (or alternatively avoided) in museums. Considerable experiences have been conducted in several countries and we need to share them: this collection of essays shows a complex, multifaceted frame that offers suggestions and ideas for further research. The museum collections, as visible signs of spiritual contents, can really contribute to encourage intercultural dialogue. Allemandi & C. On cover Kolumba. View of one of the rooms of the exhibition “Art is Liturgy. Paul Thek and the Others” (2012-2013). ISBN 978-88-422-2249-1 On the walls: “Without Title”, 28 etchings by Paul Thek, 1975-1992. Hanging from the ceiling: “Madonna on the Crescent”, a Southern-German wooden sculpture of the early sixteenth century (© Kolumba, Köln / photo Lothar Schnepf). € 25,00 Allemandi & C. RELIGION AND MUSEUMS Immaterial and Material Heritage EDITED BY VALERIA MINUCCIANI UMBERTO ALLEMANDI & C. TORINO ~ LONDON ~ NEW YORK Published by Umberto Allemandi & C. Via Mancini 8 10131 Torino, Italy www.allemandi.com © 2013 Umberto Allemandi & C., Torino all rights reserved ISBN 978-88-422-2249-1 RELIGION AND MUSEUMS Immaterial and Material Heritage edited by Valeria Minucciani On cover: Kolumba. -

Aristotelian Rhetoric in Homer

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1959 Aristotelian Rhetoric in Homer Howard Bernard Schapker Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Schapker, Howard Bernard, "Aristotelian Rhetoric in Homer" (1959). Master's Theses. 1693. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/1693 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1959 Howard Bernard Schapker ARISTOTELIAN R1mfDRIC IN RlMIR by Howard B. So.plc.... , 5.J. A Th•• le S._ltt.ad In Partial , .. lIIIMnt. of t~ ~lr.-.n'. tor the 0.0'•• of Mas'er 01 Art. Juna 19$9 LIFE Howard B.rnard Schapker was born In Clnclnnat.I, Ohio. Febru ary 26, 1931. He attended St.. Cathe,lne aral&llnr School, Clnclnnat.i, trom 1931 to 1945 and St. xavIer Hlgb School, tbe .... cU.y, troll 1945 to 1949. Fr•• 1949 to 19S.3 be attend" xavier University, Clncln.. natl. In Jun., 19S3. h. va. graduat." troll xavier University vltll the degr•• of Bachelor ot Art.. on A.O.' S, 1953, he ent..red the Soclet.y of J •• us at Miltord, Oblo. The autbor Mgan his graduate .tucU.. at Loyola Un lve.. a 1 toy. Cblcago, In september, 19S5. -

Cervical Cancer Studies on Prevention and Treatment Darlin, Lotten

Cervical cancer studies on prevention and treatment Darlin, Lotten 2013 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Darlin, L. (2013). Cervical cancer studies on prevention and treatment. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Lund University. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Cervical cancer studies on prevention and treatment Lotten Darlin DOCTORAL DISSERTATION by due permission of the Faculty of Medicine, Lund University, Sweden. To be defended at Kvinnokliniken´s Lecture Hall. Date 13th of December 2013 at nine o´clock Faculty opponent Prof. Helga Salvesen 1 Cervical cancer studies on prevention and treatment Lotten Darlin 3 Copyright Cover: Magnus Olsson Copyright Lotten Darlin Lund University, Faculty of Medicine Doctoral Dissertation Series 2013:142 ISBN 978-91-87651-17-5 ISSN 1652-8220 Printed in Sweden by Media-Tryck, Lund University Lund 2013 En del av Förpacknings- och Tidningsinsamlingen (FTI) 4 Stor är människans strävan, Stora de mål hon satt – Men mycket större är människan själv Med rötter i alltets natt. -

Major Bowes Amateur Magazine 3403.Pdf

T HE MAGAZINE OF TWENTY MILLION LISTENERS MAGAZINE MARCH 25 CENTS T HIS ISS U E AMATEUR S IN PICTURES AND STORY HAMBURGER MARY THE YOUMAN BROS. DIAMOND·TOOTH MARY PE~RY THE GARBAGE TENOR SARA BERNER DORIS WESTER VERONICA MIMOSA BU$·BOY DUNNE WYOMING JACK O'BRIEN AND- FIFTY OTHERS • SUCCESS STORIES lilY PONS DAVID SARNOFF ROSA PONSELLE EDWIN C. HILL AMELIA EARHART LAWRENCE TIBBETT FRED A5TAIRE GR .... YAM McNAMEE AND OTHERS • SPECIAL FEATURES MAJOR BOWES-HIS STORY GENE DENNIS WOMEN'S EXCLUSIVE FASHIONS •• •• AND MEN'S YOUR LOOKING GLASS LOWDOWN ON BROADWAy •••• AND HOllYWOOD NIGHT AT THE STUDIO AMATEURS' HALL OF FAME LOOKING BACKWARD FAMOUS AMATEURS OF HISTORY PICTURE TABLOID AND OTHER FEATURES REVOLUTIONARY! ACTUALLY WIPES WINDSHIELDS o C leans Because It Drains! I - I (' I ' I "~ the fil '~ 1 I'crd .I1'",>I" I'IIICIlI in \l indshid.1 wi pe r ], I:u/, ·.. - a n; \"olul iUllan" " vl1 slrut:! iUII I h at kee ps windshields .. Ie,OWI' a 11.1 .h-i(' I'. TIle Uc,, -Hidc il la.l c cO lisish of a Iw l· low. I'l'dol"alc .1 tulle o f Foft. carlWII·lJasc rll],l,c r, SC i ill " slwf, of stain ic;;;; iilcel. A~ l ilt, blade sweep! OI cross the g la ~s . .. h c nHlt,· ,II','as of I" "C:", III"O .lIul \'a CIIIIII1 arc c rca tcII, fore· ill ;': wal(" ," throll;.: h Ihe holl's aTH I COII ,,- talltir cl c allil1~ the w i!,i!! ;! ,"ill,;. .1 \ IIlIltilly w ilillshie hi w-ill I, c cleallctl lillII'll ra ~l l'I" . -

Surname Given Name Death Date Death Year Birth Date Cemetery

Surname Given Name Death Date Death Year Birth Date Cemetery Oakes Edith 2/4/1940 Mt Pleasant Cemetery, Seattle, WA Oakes Kenneth C 1965 Oakes Martin 1931 Oakley Helena Ann 1946 Oakley Thomas 1942 Oakley Tom O'Daire 1946 Oaks Daniel G 1962 Oaks Thomas 1921 Oathout George W 1919 Oathout Lee 1948 Oathout Margaret L 1933 Oathout Mary Lula 1951 Oatney Arthur S 1951 Oatney Clarence Eugene 1965 Oatney Isabelle 1936 Oatney Jean 1926 Oatney Joseph J 1936 Oatney Minnie L 1952 Oberg Maurene E 1927 O'Berg John 1941 Oberlander Rudy L 1966 Oberlee Martin 1967 Oberly Acey Jr 9-Sep-40 Lawton, OK Obermiller Henry A 1963 Obern Napoleon 1943 Oberson Elvina 1954 Oberson Henry Louis 1937 Obey H 1906 O'Bleness Ellsworth 1949 O'Bleness Nellie 1933 Obrien Baby 1939 O'Brien Edward H 1963 O'Brien Edward Joseph 1963 O'Brien Francis M 1933 O'Brien James 1893 O'Brien James Edward 1947 O'Brien Joseph 3/10/1951 O'Brien Laura 1937 O'Brien Lauria 1937 O'Brien Mary 1927 O'Brien Matilda 1929 O'Brien Ned 1956 O'Brien Robert 1936 O'Brien Santiago Jr 1956 O'Brien Stephanie Katrina 1964 O'Brien T J 1962 Surname Given Name Death Date Death Year Birth Date Cemetery O'Brien Thomas Sr 1962 O'Brien Vincent Anthony 1956 O'Brien William J 1956 O'Brien William J 1967 O'Brine Charles 1969 Ocampo April Grace Ochoa Anna Louise 1968 Ochoa Magdalena S 1952 Ochoa Magdalene 1952 Ochoa Rose 1951 Ocker Anna H 1954 Ocker Carrie Fern 1962 Ocker Chas Marion 1921 Ocker Fillmore Raymond 1967 Ocker Raymond Lewis 1949 O'Connar Alva 1969 O'Connar Hilda I 1924 O'Connar John O 1930 O'Connar Lucy 1923 -

America in My Childhood

Swedish American Genealogist Volume 22 Number 2 Article 2 6-1-2002 America in My Childhood Ulf Beijbom Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/swensonsag Part of the Genealogy Commons, and the Scandinavian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Beijbom, Ulf (2002) "America in My Childhood," Swedish American Genealogist: Vol. 22 : No. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/swensonsag/vol22/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Swenson Swedish Immigration Research Center at Augustana Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swedish American Genealogist by an authorized editor of Augustana Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. America in My Childhood Ulf Beijbom * "Moshult was a little part of the world where thoughts of distant places usually did not stretch any farther than to Skruv and Emmaboda," tells the old cantor Ivar Svensson in the Algutsboda book. The exception, of course, was America, which was always in the thoughts of the people of Algutsboda during the time when Vilhelm grew up. America had become a household word, comparable to heaven. The blissful lived there, but could not be seen. Here, as in most other parishes in Smaland, America was considered a western offshoot to the home area. This was especially true about Minnesota and Chisago County, "America's Smaland," which became the most common destination for the emigrants from Algutsboda and Ljuder parishes. Most people in the area had only a vague idea about the Promised Land or the U.S.A. -

13 Jul 1869-1 Jan 1874 Grooms a - Z

Lawrence County, Ohio Marriage Indexes Book 10 13 Jul 1869-1 Jan 1874 Grooms A - Z Groom Surname Groom First Name Bride Surname Bride First Name Page Abbott Patrick Mullen Ellen 287 Abrams John W. Smith Mary J. 444 Abshin Joseph Dora Belva 272 Abshire William Edwards Sarah A. 528 Ackerman James T. Mays Rhoda J. 218 Adams Amos Suiter Sarah C. 371 Adams Elias Coburn Sarah Jane 282 Adams Hamilton Frazier Ellen 130 Adams Hamlin M. Ferguson Jennie S. 527 Adams Henry McKinney Mary 216 Adams Madison McMaster Nancy 63 Adams Washington Layne Nancy 247 Addis Thomas M. Delaney Jane 565 Addis William A. Blagg Myra E. 433 Adkins Charles Mannon Polly 165 Adkins Johnson Adkins Dicy A. 95 Adkins William Powell Sarah 323 Adsit Byron D. George Emma 550 Akerman Joseph R. Wood Marinda 572 Akers James H. Burchett Nancy J. 342 Akers Robert V. Sturgill Malissa 517 Albert Coscinsco Harrison Nancy 385 Aleshier Francis M. Null Sarah 307 Alexander Robert S. Hays Anna M. 295 Allaway George Cron Jane 577 Allen Edgar W. Dempsey Jennie W. 571 Allen John (col) Burventer Elizabeth J. 106 Allen Sam’l. M. Waller M. 162 Allmond Joshua M. Nesmith Ellen 574 Amos H.L. Goff Julia A. 141 Anducut Gabriel Marcum Eliza 113 ©The Lawrence Register Lawrence County, Ohio Marriage Indexes Book 10 13 Jul 1869-1 Jan 1874 Grooms A - Z Ankrim George C. Wood Sarah A. 349 Ansonton Charles (col) Wright Mary 112 Arbaugh Isaac, Jr. Aldridge Nancy E. 21 Arbaugh Wm. A. Gibson Sally 77 Arms Charles K. -

Annual Conference Journals Index to Memoirs

Annual Conference Journals Index to Memoirs Surname First Name Spouse/Father Death/Funeral Date Journal Page Abbott Cleon Frederick Carol 10/6/1994 DC1995 308 Abbott William B. Olive 12/27/1969DC1970 957 Ackerman C.A. UB1946 31 Ackerman Mildred Earl 11/23/1976 DC1977 931 Adams Carl G. Emma Ruth Luzzader 10/2/1981DC1982 1567 Adams Carlos L. Emma Louise Cooper; Flora 8/20/1941 DC1942 550 Kempf Adams Emma Louise Cooper Carlos L. 11/12/1913DC1914 326 Adams Flora Kempf Carlos 8/15/1962DC1963 1135 Adams Robert 12/20/1931 EV1932 55 Ainge Clement Margaret Kershaw 1/30/1948 DC1948 182 Ainge Margaret Kershaw Clement 11/12/1934 DC1935 130 Ainsworth Miriam Ada H. William P 5/28/1954 DC1954 736 Ainsworth William P. Ada; Ethel May Carefoot 10/30/1965DC1966 1046 Alabaster Harriet Ann Bemish J. 10/17/1881 DC1882 37 Albery Paul Franklin Alice Nutting; Mary Barber 11/16/2006 DC2007 219 Willoughby Albig Hattie Loose Orville M. 8/26/1938 EV1939 52 Albig Orville M. Hattie Loose; Ella 2/8/1965 EUB1965 138 Albro Addis Mary Alice Scribner 10/15/1911 DC1912 44 Albro Mary Alice Scribner Addis 8/12/1905 DC1905 184 Allen Adelaide A. Andrews C.B. 11/3/1948 DC1949 448 Allen Alfred Louisa J. Hartwell 1/29/1903 DC1903 40 Allen Bertram E. Ida E. Hunt 5/28/1925DC1925 322 Allen Charlena Letts Eugene 10/9/1947 DC1948 186 Allen Charles Bronson Blanche 3/31/1953 DC1953 462 Allen Charles Thompson Elnora Root 10/12/1904DC1905 162 Allen Eugene Minnie M. -

A/R Contacts

A/R Contacts Agency ID Agency Honor Roll SWARM Contact Phone 100 Department of Human 2019 Gerold Floyd (503) 378-2709 Services Contact Phone Ext. Email Heidi Baker (503) 945-6012 mailto:[email protected] Julie Strauss (503) 947-5125 mailto:[email protected] Agency ID Agency Honor Roll SWARM Contact Phone 107 Department of Administrative 2019 Theresa Gahagan (503) 373-0711 Services Contact Phone Ext. Email Brad Cunningham (503) 378-3553 mailto:[email protected] Mini Fernandez (503) 378-3710 mailto:[email protected] Bill Lee(503) 373-0318 mailto:[email protected] Yekaterina Medvedeva (503) 378-3706 mailto:[email protected] Agency ID Agency Honor Roll SWARM Contact Phone 108 Mental Health Regulatory 2019 Theresa Gahagan (503) 373-0711 Agency Contact Phone Ext. Email Charles Hill (503) 378-5499 4 mailto:[email protected] LaRee Felton (503) 373-1196 mailto:[email protected] Lindsey McFadden(503) 378-8056 mailto:[email protected] Agency ID Agency Honor Roll SWARM Contact Phone 109 Department of Aviation 2019 Theresa Gahagan (503) 373-0711 Contact Phone Ext. Email Kristen Forest (503) 378-2522 mailto:[email protected] Roger Sponseller (503) 378-5480 mailto:[email protected] Friday, April 10, 2020 Page 1 of 33 A/R Contacts Agency ID Agency Honor Roll SWARM Contact Phone 114 Office of the Long Term Care 2019 Theresa Gahagan (503) 373-0711 Ombudsman Contact Phone Ext. Email Ashley Cottingham (503) 779-8806 mailto:[email protected] Katy Moreland (503) 373-0257 mailto:[email protected] Agency ID Agency Honor Roll SWARM Contact Phone 115 Employment Relations Board 2019 Gerold Floyd (503) 378-2709 Contact Phone Ext. -

12/13/2010 CEMETERY Page 1 FIRST NAME MIDDLE LAST NAME

CEMETERY 12/13/2010 FIRST NAME MIDDLE LAST NAME BIRTH DATE DEATH DATE LOT # BLOCK # DESCRIPTION Craig L. Abbott 11/20/1975 10/4/1997 96 8 Donald Abbott 96 8 Sharon Abbott 96 8 Acricol Abercrombie 1860 1944 111 2 Ida F. Abercrombie 1863 1948 111 2 Isaac M. Abercrombie 1869 1943 5 5 Issac M. Abercrombie 74 yrs. 9/10/1907 5 5 Kenneth B. Abercrombie 8/24/1896 6/24/1954 111 2 Mary Abercrombie 4/22/1832 9/15/1909 5 5 Odie E. Abercrombie 1872 1957 5 5 R. J. Ackelson 28 yrs. 11/10/1894 31 4 Chis E. Ackerman 3/4/1905 2/19/1974 135 7 Clara L. Ackerman 5/6/1913 39 7 Fern Ackerman 8/6/1911 5/22/1996 177 1 Hazel Viola Ackerman 7/31/1905 9/17/1927 177 1 Henry E. Ackerman 5/31/1917 8/18/1968 39 7 Herman E. Ackerman 8/22/1902 6/4/1959 177 1 John E. Ackerman 6/10/1898 4/15/1945 137 1 Lorena A. Ackerman 11/13/1911 3/20/1977 98 7 Maxine L. Ackerman 10/15/1917 9/6/1978 135 7 Opal A. Ackerman 2/16/1892 7/3/1984 137 1 Phyllis C. Ackerman 10/21/1939 2/9/1996 126 8 Richard O. Ackerman 2/13/1911 7/6/1993 98 7 Spencer R. Ackerman 6/22/1996 12/11/1996 127 8 Elvina Karlson Adams 1/30/1889 1/19/1965 18 4 Hattie Adams 2/18/1863 9/24/1955 115 1 Mary M. -

A Short Biography of Heinrich Witt*

A Short Biography of Heinrich Witt* Christa Wetzel The following short biography reconstructs Heinrich Witt’s life according to the information provided by his diary as well as from other sources. It is limited to presenting the main lines of the course of his life – in the full knowledge that any definition of a life’s “main lines” is already an interpretation. A common thread of the narration, apart from those personal data and events as one expects from a biography (birth, family, education, vocation, marriage, death), are the business activities of Heinrich Witt as a merchant. Thus, the description of his life gives a sketch of the economic and social networks characterizing the life, both mobile and settled, of Heinrich Witt as a migrant. However, this biography will not and cannot provide a detailed description of each of Witt’s business activities or of his everyday life or of the many people to which he had contact in Germany, Europe and Peru. Even if, according to Bourdieu, the course a life has taken cannot be grasped without knowledge of and constant reflection on the “Metro map”, this biography also does not give a comprehensive description of the period, i.e. of the political, economic, social and cultural events and discourses in Peru, Europe or, following Witt’s view, on the entire globe.1 Furthermore, this rather “outward” biography is not the place to give a reconstruction of Witt’s world of emotions or the way in which he saw and reflected on himself. All this will be left to the discoveries to be made when reading his diary. -

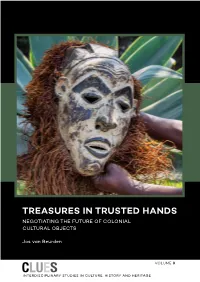

Treasures in Trusted Hands

Van Beurden Van TREASURES IN TRUSTED HANDS This pioneering study charts the one-way traffic of cultural “A monumental work of and historical objects during five centuries of European high quality.” colonialism. It presents abundant examples of disappeared Dr. Guido Gryseels colonial objects and systematises these into war booty, (Director-General of the Royal confiscations by missionaries and contestable acquisitions Museum for Central Africa in by private persons and other categories. Former colonies Tervuren) consider this as a historical injustice that has not been undone. Former colonial powers have kept most of the objects in their custody. In the 1970s the Netherlands and Belgium “This is a very com- HANDS TRUSTED IN TREASURES returned objects to their former colonies Indonesia and mendable treatise which DR Congo; but their number was considerably smaller than has painstakingly and what had been asked for. Nigeria’s requests for the return of with detachment ex- plored the emotive issue some Benin objects, confiscated by British soldiers in 1897, of the return of cultural are rejected. objects removed in colo- nial times to the me- As there is no consensus on how to deal with colonial objects, tropolis. He has looked disputes about other categories of contestable objects are at the issues from every analysed. For Nazi-looted art-works, the 1998 Washington continent with clarity Conference Principles have been widely accepted. Although and perspicuity.” non-binding, they promote fair and just solutions and help people to reclaim art works that they lost involuntarily. Prof. Folarin Shyllon (University of Ibadan) To promote solutions for colonial objects, Principles for Dealing with Colonial Cultural and Historical Objects are presented, based on the 1998 Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art.