Florida Historical Quarterly, Volume 78, Number 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turks and Caicos Islands

Important Bird Areas in the Caribbean – Turks and Caicos Islands ■ TURKS & CAICOS ISLANDS LAND AREA 500 km2 ALTITUDE 0–49 m HUMAN POPULATION 21,750 CAPITAL Cockburn Town, Grand Turk IMPORTANT BIRD AREAS 9, totalling 2,470 km2 IMPORTANT BIRD AREA PROTECTION 69% BIRD SPECIES 204 THREATENED BIRDS 3 RESTRICTED-RANGE BIRDS 4 MIKE PIENKOWSKI (UK OVERSEAS TERRITORIES CONSERVATION FORUM, AND TURKS AND CAICOS NATIONAL TRUST) Caribbean Flamingos on the old saltpans at Town Salina, in the capital, Grand Turk. (PHOTO: MIKE PIENKOWSKI) INTRODUCTION Middle and South Caicos are inhabited, and resorts are being developed on many of the small island. The smaller Turks The Turks and Caicos Islands (TCI), a UK Overseas Territory, Bank holds the inhabited islands of Grand Turk (10 km by 3 lie north of Hispaniola as a continuation of the Bahamas km) and Salt Cay (6 km by 2 km), as well as numerous smaller Islands chain. The Caicos Islands are just 50 km east of the cays. southernmost Bahamian islands of Great Inagua and The Turks Bank islands plus South Caicos (the “salt Mayaguana. The Turks and Caicos Islands are on two shallow islands”) were used to supply salt from about 1500. They were (mostly less than 2 m deep) banks—the 5,334 km² Caicos Bank inhabited by the 1660s when the islands were cleared of trees and the 254-km² Turks Bank—with deep ocean between them. to facilitate salt production by evaporation. By about 1900, There are further shallow banks, namely Mouchoir, Silver and Grand Turk was world famous for its salt. -

Turks and Caicos

Riskline / Country Report / 29 August 2021 TURKS AND CAICOS Overall risk level High Reconsider travel Can be dangerous and may present unexpected security risks Travel is possible, but there is a potential for disruptions Overview Upcoming Events 01 September 2021 - 02 September 2021 Medium risk: Entry to be limited to vaccinated travellers only from 1 September – Update Effective 1 September, only travellers with a proof of a full vaccination against COVID-19 by a Pfizer/BioNTech, Moderna, AstraZeneca or Johnson and Johnson vaccine at least 14 days prior to arrival will be allowed entry. A negative COVID-19 test no older than 72 hours and an insurance that covers COVID-19 are also required. Those in transit or under 16 years, medically exempted travellers and crew members are exempted. Riskline / Country Report / 29 August 2021 / Turks and Caicos 2 Travel Advisories Riskline / Country Report / 29 August 2021 / Turks and Caicos 3 Summary Turks and Caicos is a High Risk destination: reconsider travel. High Risk locations can be dangerous and may present unexpected security risks. Travel is possible, but there is a potential for severe or widespread disruptions. Covid-19 High Risk An uptick in infection rates prompted authorities to reimpose curfew measures from November 2020. A slight increase in infection rates was reported in July, although the rates have reduced considerably since February. A curfew remains in effect, however. International travel has resumed. Political Instability Low Risk A parliamentary dependency of the United Kingdom (UK), the Turks and Caicos Islands are led by Premier Washington Misick, the local representative who liaises with his British counterpart, Governor Nigel Dakin. -

A Revisit to a Lightkeeper's Home

A REVISIT TO A LIGHTKEEPER'S HOME It was an isolated place wh ere th e kids would dash to the fla gpole to dip the insigne in salute when a yacht or ship passed the lighthouse station and re ceived a returning toot. The air was clean, the water cyrstal clear, game and fish sufficient to f eed thefamilies, remote, but not a "lonely place" as some p eople may believe. Three dau ght ers of former lighthouse keepers retu rn to By Hibb ard Casselb erry, Jr. the station for a visit in 1976. They are, from left to right, Ruth Isler Hedden, Mary Knight Voss, and lora Driving north on AlA from Pomp ano Beach to Isler Saxon. the Hillsboro Inlet and the lighthouse station on its north shore, three daughters of former lighthouse Hibbard Casselberry, Jr.. is an architectural de keepers re me mbered that the road was not always signer and planner. a certified building inspector, so smooth nor congested. Zora Isler Saxon, sitting and a construction specification writer. He has next to her younger sister, Ruth Isler Hedden, served as editorfor several trade publications and said, "Part of it was an awful road, with sharp has written extens ively on gen ealogy . white gravel." Mary Knight Voss remembered, "The Beach Road (Atlantic Blvd .) in the early 1920s was only a gravel road to the bea ch area and the road north In the late 1800s, the south part of Florida's (AlA) was a ru tted sa nd road that ended here at peninsula was very sparsely populated. -

John F. Kennedy Space Center

1 . :- /G .. .. '-1 ,.. 1- & 5 .\"T!-! LJ~,.", - -,-,c JOHN F. KENNEDY ', , .,,. ,- r-/ ;7 7,-,- ;\-, - [J'.?:? ,t:!, ;+$, , , , 1-1-,> .irI,,,,r I ! - ? /;i?(. ,7! ; ., -, -?-I ,:-. ... 8 -, , .. '',:I> !r,5, SPACE CENTER , , .>. r-, - -- Tp:c:,r, ,!- ' :u kc - - &te -- - 12rr!2L,D //I, ,Jp - - -- - - _ Lb:, N(, A St~mmaryof MAJOR NASA LAUNCHINGS Eastern Test Range Western Test Range (ETR) (WTR) October 1, 1958 - Septeniber 30, 1968 Historical and Library Services Branch John F. Kennedy Space Center "ational Aeronautics and Space Administration l<ennecly Space Center, Florida October 1968 GP 381 September 30, 1968 (Rev. January 27, 1969) SATCIEN S.I!STC)RY DCCCIivlENT University uf A!;b:,rno Rr=-?rrh Zn~tituta Histcry of Sciecce & Technc;oGy Group ERR4TA SHEET GP 381, "A Strmmary of Major MSA Zaunchings, Eastern Test Range and Western Test Range,'" dated September 30, 1968, was considered to be accurate ag of the date of publication. Hmever, additianal research has brought to light new informetion on the official mission designations for Project Apollo. Therefore, in the interest of accuracy it was believed necessary ta issue revfsed pages, rather than wait until the next complete revision of the publiatlion to correct the errors. Holders of copies of thia brochure ate requested to remove and destroy the existing pages 81, 82, 83, and 84, and insert the attached revised pages 81, 82, 83, 84, 8U, and 84B in theh place. William A. Lackyer, 3r. PROJECT MOLL0 (FLIGHTS AND TESTS) (continued) Launch NASA Name -Date Vehicle -Code Sitelpad Remarks/Results ORBITAL (lnaMANNED) 5 Jul 66 Uprated SA-203 ETR Unmanned flight to test launch vehicle Saturn 1 3 7B second (S-IVB) stage and instrment (IU) , which reflected Saturn V con- figuration. -

November 2020

South Brevard Historical Society, Inc. Founded 1966 E Newsletter NOVEMBER 2020 DEAR MEMBERS AND FRIENDS, This month provides two opportunities to celebrate Our Nation. The first, our opportunity to vote in the presidential election of 2020. As we await the final, end of all votes counted, tally I am reminded of a Yogi Bera quote, “it ain’t over til it’s over”. (I did fact check that and it was credited to his words of encouragement to the Mets in the 1973 pennant race.) The origin of another phrase that came to mind seems forgotten in time but I suspect is echoed by many, “it’s all over but the shouting.” The quote that is my prayer and hope for our country is from the poem “America the Beautiful” by Katherine Lee Bates……”and crown thy good wth brotherhood from sea to shining sea”. May we remember that we are the UNITED States and let us “move on.com”. November also provides VETERANS DAY a special time to honor all who have served in the military. Originally called Armistice Day, the holiday celebrated the agreement to end the fighting of WWI on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month in 1918. Following WWII and the Korean War, the name was changed to Veterans Day and the purpose expanded in the U.S. to honor all who serve in the military. During this “time of difficulty” many of us have begun to research and write our family histories. So, it is appropriate that our special feature this month is an essay written in 2008, the 90 th anniversary of the end of WWI, by SBHS board member Nancy Grout about her grandfather, Sidney Emerson Grout, a veteran of WWI. -

12' Spacecraft

' - NA'I',NAL AER /'iAJIICS AYD SPACE ADMINISTRATION Am 2-41 55 NAS+1INCTON D C 29546 lELSHJg 2-69'_5 FOR RELEASE: SUNDAY August 21, 1966 RELEASE NO: 66-213 . PROJECT: Apollo/Saturn 202 (To be launched no E earlier than Aug. 25) S CONTENTS S i b U ITHRU) z0 UCCESSION NUMBER) 0 (CODE) T -D. (PAGES) 4 2 31 (CATEGORY) (NASA CR OR TMX OR AD NUMBER) RELXASE NO: 66-213 APOLLO SATURN HEAT SHIELD IN ORBIT TEST The third unmanned Apolloflprated Saturn I flight will be launched no earlier than Aug. 25. Thfs will be the second flight test of the Apollo spacecraft command and service modules and the third flight test of the Saturn I rocket in pre- paration for manned rnissicns orbiting the Earth. The 17,825-mile flight will carry the spacecraft three- quarters of the way around the Earth. Landing will be in the north central Pacific about 300 miles southeast of Wake Island. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration will launch the space vehicle from Launch Complex 34, Kennedy Space Center, Fla., at l2:3O a.m. EDT to provide a long period of daylight for spacecraft recovery operations. The flight will take almost 93 minutes. The mission is the second performance check of the Apollo command module ablative heat shield. The shield will be subjected to extended high heat loads -- about 23,000 BTU/per square foot -- resulting from a reentry path resembling a "roller coaster" ride on Earth. -more- 8/15/66 -2 - On the first unmanned Apollo mission last February, the heat shield underwent high heating rates at a very steep angle. -

The Criminal's Belief System: Why Criminals Do the Things They Do, by Linda A

The Criminal’s Belief System Why Criminals Do the Things They Do By Linda A. Ratcliff, Th.D., Ed.D. Copyright 2016 Linda A. Ratcliff, Th.D., Ed.D. Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means – for example, electronic, photocopy, recording - without the prior written permission of the author. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews. The Criminal's Belief System: Why Criminals Do the Things They Do, by Linda A. Ratcliff Table of Contents Introduction Guard Your Heart 3 Chapter 1: “It’s All About Me, Me, Me!” 6 Chapter 2: “What’s Mine is Mine. What’s Yours is Mine Too!” 9 Chapter 3: “It’s My Way or the Highway.” 13 Chapter 4: “It’s Not My Fault.” 17 Chapter 5: “That Wasn’t Fair.” 20 Chapter 6: “Whatever!” 24 Chapter 7: “I Can’t.” 27 Chapter 8: “I Didn’t Do Anything Wrong.” 30 Chapter 9: “Nothing Scares Me.” 33 Chapter 10: “I Can’t Help It.” 36 Chapter 11: “I’m Above the Law.” 39 Chapter 12: “He Only Got What He Deserved.” 42 Chapter 13: “No One Will Ever Know.” 45 Chapter 14: “I Won’t.” 48 Chapter 15: “I Don’t Get Mad. I Get Even.” 51 Chapter 16: “Man … This Is a drag.” 54 Chapter 17: “That's None of Your Business.” 57 Chapter 18: “I Want It NOW!” 61 Chapter 19: “I’ll Git’er Done Tomorrow.” 65 Chapter 20: “I Won’t Get Caught.” 68 Chapter 21: “I’m Basically a Good Person.” 71 Chapter 22: “He Did It.” 73 Chapter 23: “I Didn’t Mean To.” 76 Chapter 24: “I Was Desperate.” 80 2 Therapon University: Validating People – One Degree at a Time The Criminal's Belief System: Why Criminals Do the Things They Do, by Linda A. -

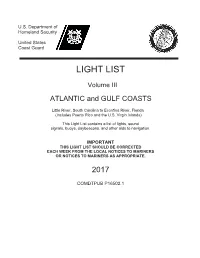

USCG Light List

U.S. Department of Homeland Security United States Coast Guard LIGHT LIST Volume III ATLANTIC and GULF COASTS Little River, South Carolina to Econfina River, Florida (Includes Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands) This /LJKW/LVWFRQWDLQVDOLVWRIOLJKWV, sound signals, buoys, daybeacons, and other aids to navigation. IMPORTANT THIS /,*+7/,67 SHOULD BE CORRECTED EACH WEEK FROM THE LOCAL NOTICES TO MARINERS OR NOTICES TO MARINERS AS APPROPRIATE. 2017 COMDTPUB P16502.1 C TES O A A T S T S G D U E A T U.S. AIDS TO NAVIGATION SYSTEM I R N D U 1790 on navigable waters except Western Rivers LATERAL SYSTEM AS SEEN ENTERING FROM SEAWARD PORT SIDE PREFERRED CHANNEL PREFERRED CHANNEL STARBOARD SIDE ODD NUMBERED AIDS NO NUMBERS - MAY BE LETTERED NO NUMBERS - MAY BE LETTERED EVEN NUMBERED AIDS PREFERRED RED LIGHT ONLY GREEN LIGHT ONLY PREFERRED CHANNEL TO CHANNEL TO FLASHING (2) FLASHING (2) STARBOARD PORT FLASHING FLASHING TOPMOST BAND TOPMOST BAND OCCULTING OCCULTING GREEN RED QUICK FLASHING QUICK FLASHING ISO ISO GREEN LIGHT ONLY RED LIGHT ONLY COMPOSITE GROUP FLASHING (2+1) COMPOSITE GROUP FLASHING (2+1) 9 "2" R "8" "1" G "9" FI R 6s FI R 4s FI G 6s FI G 4s GR "A" RG "B" LIGHT FI (2+1) G 6s FI (2+1) R 6s LIGHTED BUOY LIGHT LIGHTED BUOY 9 G G "5" C "9" GR "U" GR RG R R RG C "S" N "C" N "6" "2" CAN DAYBEACON "G" CAN NUN NUN DAYBEACON AIDS TO NAVIGATION HAVING NO LATERAL SIGNIFICANCE ISOLATED DANGER SAFE WATER NO NUMBERS - MAY BE LETTERED NO NUMBERS - MAY BE LETTERED WHITE LIGHT ONLY WHITE LIGHT ONLY MORSE CODE FI (2) 5s Mo (A) RW "N" RW RW RW "N" Mo (A) "A" SP "B" LIGHTED MR SPHERICAL UNLIGHTED C AND/OR SOUND AND/OR SOUND BR "A" BR "C" RANGE DAYBOARDS MAY BE LETTERED FI (2) 5s KGW KWG KWB KBW KWR KRW KRB KBR KGB KBG KGR KRG LIGHTED UNLIGHTED DAYBOARDS - MAY BE LETTERED WHITE LIGHT ONLY SPECIAL MARKS - MAY BE LETTERED NR NG NB YELLOW LIGHT ONLY FIXED FLASHING Y Y Y "A" SHAPE OPTIONAL--BUT SELECTED TO BE APPROPRIATE FOR THE POSITION OF THE MARK IN RELATION TO THE Y "B" RW GW BW C "A" N "C" Bn NAVIGABLE WATERWAY AND THE DIRECTION FI Bn Bn Bn OF BUOYAGE. -

Exploring Space

EXPLORING SPACE: Opening New Frontiers Past, Present, and Future Space Launch Activities at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station and NASA’s John F. Kennedy Space Center EXPLORING SPACE: OPENING NEW FRONTIERS Dr. Al Koller COPYRIGHT © 2016, A. KOLLER, JR. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without the written consent of the copyright holder Library of Congress Control Number: 2016917577 ISBN: 978-0-9668570-1-6 e3 Company Titusville, Florida http://www.e3company.com 0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Foreword …………………………………………………………………………2 Dedications …………………………………………………………………...…3 A Place of Canes and Reeds……………………………………………….…4 Cape Canaveral and The Eastern Range………………………………...…7 Early Missile Launches ...……………………………………………….....9-17 Explorer 1 – First Satellite …………………….……………………………...18 First Seven Astronauts ………………………………………………….……20 Mercury Program …………………………………………………….……23-27 Gemini Program ……………………………………………..….…………….28 Air Force Titan Program …………………………………………………..29-30 Apollo Program …………………………………………………………....31-35 Skylab Program ……………………………………………………………….35 Space Shuttle Program …………………………………………………..36-40 Evolved Expendable Launch Program ……………………………………..41 Constellation Program ………………………………………………………..42 International Space Station ………………………………...………………..42 Cape Canaveral Spaceport Today………………………..…………………43 ULA – Atlas V, Delta IV ………………………………………………………44 Boeing X-37B …………………………………………………………………45 SpaceX Falcon 1, Falcon 9, Dragon Capsule .………….........................46 Boeing CST-100 Starliner …………………………………………………...47 Sierra -

The Tallahassee Bus Protest

FIELD REPORTS ON DESEGREGATION IN THE SOUTH THE TALLAHASSEE BUS PROTEST by CHARLES U. SMITH Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University and LEWIS M. KILLIAN Florida State University Published by the ANTI-DEFAMATION LEAGUE OF B'NAI B'RITH with the cooperation of THE COMMITTEE ON INTERGROUP RELATIONS THE SOCIETY FOR THE STUDY OF SOCIAL PROBLEMS ; י/ r February, 1958 Published by the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith 515 Madison Avenue, New York 22, N. Y. Officers: HENRY EDWARD SCHULTZ, chairman; MEIER STEINBRINK, honorary chairman; BARNEY BALABAN, A. G. BALLENGER, HERBERT H. LEHMAN, LEON LOWENSTEIN, WILLIAM SACHS, BENJAMIN SAMUELS, MELVIN H. SCHLESINGER, JESSE STEINHART, honorary vice-chairmen; JOSEPH COHEN, JEFFERSON E. PEYSER, MAX J. SCHNEIDER, vice-chairmen; BENJAMIN GREENBERG, treasurer; HERBERT LEVY, secretary; BENJAMIN R. EPSTEIN, national director; BERNARD NATH, chairman, executive committee; PAUL H. SAMPLINER, vice-chairman, executive committee; PHILIP M. KLUTZNICK, president, B'nai B'rith; MAURICE BISGYER, executive vice-president, B'nai B'rith. Staff Directors: NATHAN C, BELTH, press relations; OSCAR COHEN, program; ARNOLD FORSTER, civil rights; ALEXANDER F. MILLER, community service; J. HAROLD SAKS, administration; LESTER J. WALDMAN, executive assistant. Series Editor: OSCAR COHEN, national director, program division. THE TALLAHASSEE BUS PROTEST Community Background Tallahassee is a small city (population 27,237 in 1950) in a state which con- tains some of the most rapidly growing urban areas in the southeast. It is not an important industrial center. Its chief importance lies in the fact that it is the state capital. Perhaps its next most important characteristic is that it is the seat of two of the state's institutions of higher learning: Florida State University (white) and Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University (Negro). -

Driver Charged After Car Gets Stuck in Sand Brevard Schools Earn

TITUSVILLE • MIMS COCOA THE CAPE NORTH BREVARD PORT ST JOHN MERRITT ISLAND COCOA BEACH Vol. 13, No. 27 www.HometownNewsBrevard.com Friday, July 14, 2017 FLYING HIGH FUN FOR ALL CUTIE ALERT! The Henson's bring us Surfisde Playhouse Meet LilBit, our pet of with them to an air force has fun events for all the week! base in Washington. this summer. TOURING WITH THE TOWNIES 14 ENTERTAINMENT 15 PET OF THE WEEK 12 American Made Falcon 9 flies again Brevard schools • Lifetime Warranty • Over 20 colors available earn ‘A’ grade By Austin Rushnell [email protected] BREVARD COUNTY – One of the most significant factors in determining the autonomy of a person is education, Even against salty air and here in the United States, that starts with quality schooling from public insti- tutes. This summer, Brevard Public Schools Alex Schierholtz/staff photographer earned an ‘A’ grade for excellence in edu- A SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket lifts off from Launch Complex 39A at Kennedy cation, earning the district the No. 2 spot Space Center on July 5, carrying its heaviest payload to date: an Intelsat 35e among Florida’s 14 large districts. satellite. Manufactured by Boeing and equipped with an advanced digital “Improvement in our schools is always something to celebrate,” BPS Superinten- payload, Intelsat 35e will deliver high-performance services for wireless dent Desmond Blackburn said in a state- infrastructure, mobility, broadband, government and media customers in ment. “When I consider the great diversi- the Americas, the Caribbean, Europe and Africa. ty in our student population, the relatively 1220 Ridgewood Ave. -

Civil Rights Resproj

TheAFRICAN AMERICAN EXPERIENCE in North Carolina The Civil Rights Movement North Carolina Freedom Monument Project Research Project Lesson Plan for Teachers: Procedures ■ Students will read the introduction and time line OBJECTIVE: To become familiar with of the Civil Rights Movement independently, as a significant events in the Civil Rights Movement small group or as a whole class. and their effects on North Carolina: ■ Students will complete the research project independently, as a small group or as a whole class. 1. Students will develop a basic understanding of, and ■ Discussion and extensions follow as directed by be able to define specific terms; the teacher. 2. Students will be able to make correlations between the struggle for civil rights nationally and in North Evaluation Carolina; ■ Student participation in reading and discussion of 3. Students will be able to analyze the causes and the time line. predict solutions for problems directly related to dis- ■ Student performance on the research project. criminatory practices. Social Studies Objectives: 3.04, 4.01, 4.03, 4.04, 4.05, 5.03, 6.04, 7.02, 8.01, 8.03, 9.01, 9.02, 9.03 Social Studies Skills: 1, 2, 3 Language Arts Objectives: 1.03, 1.04, 2.01, 5.01, 6.01, 6.02 Resources / Materials / Preparations ■ Time line ■ Media Center and/or Internet access for student research. ■ This research project will take two or three class periods for the introduction and discussion of the time line and to work on the definitions. The research project can be assigned over a two- or three-week period.